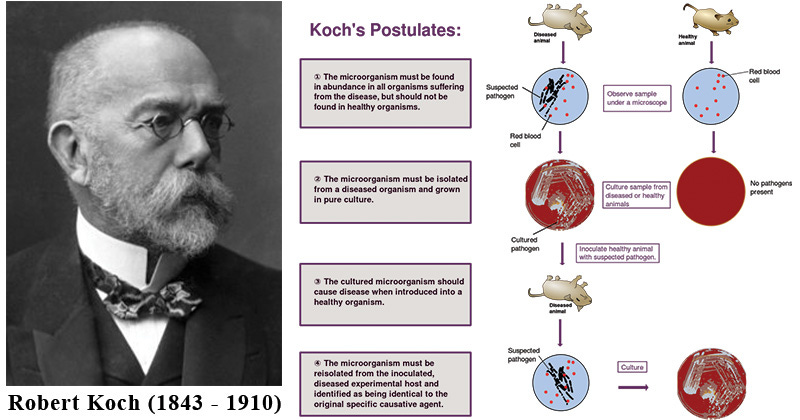

I recently went through many of the early voices who spoke out against the germ “theory” of disease from the start of its conception in the mid 1800s. These individuals provided plenty of reasons for why the germ “theory” of disease did not fit with the observations of “infectious” and “contagious” disease as seen within their own clinics. Many provided evidence that the “theory” itself should have never made it to the status of a scientific theory as the germ hypothesis had been repeatedly falsified by experimental evidence obtained throughout the years. They showed how Koch's Postulates, the logical criterion considered essential and necessary in order to prove any microbe is capable of causing disease, had never been met for any of the so-called pathogenic agents.

The evidence regularly showed that the presumed “pathogens” were commonly found within healthy hosts or in instances of “unrelated” disease. One set of investigators would find a certain bacterium associated with a certain disease, while another set would not find it at all. There were times where it looked as if the same disease could be caused by different bacteria, and that the same bacteria could produce different diseases. The agents were also not found at times within those who were suffering from the same disease. Various experiments utilizing pure cultures of a bacterium failed to produce disease in multiple instances, most infamously with Robert Koch's own attempts to prove the cholera bacillus caused the disease attributed to it. Thus, it was clear to those who looked at the issue both critically and logically, there was no scientific evidence that germs cause disease.

The voices against the germ hypothesis were adamant that it was the terrain (internal environment) of the individual that was the most important factor in determining whether or not one would experience disease. The more toxins and stressors that we are exposed to over a period of time, the greater the chance there will be that the body will initiate a detoxification process from within due to experiencing a toxic overload. Today, we can see that our terrain is directly influenced by many different factors, including:

Consuming non-organic, genetically modified, pesticide-laden foods

Drinking unclean, fluoridated and chlorinated water

Living a sedentary lifestyle without regular exercise

Consuming alcohol and recreational drugs

Taking prescription medications and toxic vaccines

Interrupted or inconsistent sleep cycle

Lack of direct sunlight

Long-term exposure to EMF’s and other radiation

Overabundance of stress and fear

Regular use of cleaning supplies and other chemicals

Regular exposure to air pollution

Improper self-care and hygiene

This became known as the terrain theory. It states that it is not strictly a single cause that brings about disease, as it can be many factors acting in combination with each other that toxifies the internal environment of an individual, eventually tipping the scale leading to a state of disease. Essentially, the dis-ease is the body working to cleanse itself in order to restore homeostasis.

While the germ “theory” should have never had made it to its current status as the prominent paradigm explaining disease, there were powerful and vested interests who worked to keep the disproven and falsified hypothesis alive, fraudulently elevating it to the status of a scientific theory based upon nothing but pseudoscientific evidence. Researchers, including Robert Koch himself, created ways to try and skirt around the logic-based Postulates in order to keep the falsified results intact, such as with the creation of the concept of the asymptomatic carrier state and the existence of an “immune” system. They shrugged off the inability to grow certain microbes in pure cultures, and the requirement to recreate the exact same disease in animal and human experiments was cast aside. Basic logic was thrown out the window.

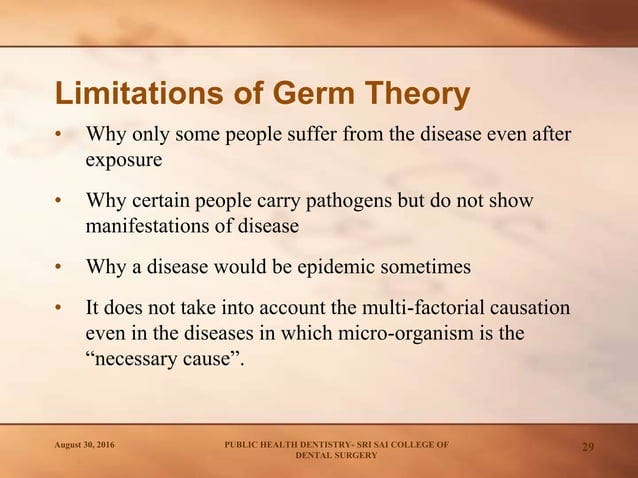

However, even with the attempts to bandage up the disproven and falsified hypothesis into a pseudoscientific theory, the cracks are very apparent for all to see, even for the true believers. There are just too many holes that cannot be explained by the germ “theory” of disease as it is. These chinks in the microbial armor can actually lead proponents of the germ “theory” to question its limitations, bringing them, in turn, to second guess the paradigm as they embrace elements of the terrain theory perspective in order to explain the glaring discrepancies.

With that in mind, presented below are two voices within the scientific community, Dr. Gordon T. Stewart and Rene Dubos, who actually questioned the germ “theory” dogma by highlighting the many ways in which it fails to explain how microbes are the strict cause of disease. While these two individuals were by all accounts firmly in the germ “theory” camp, their papers highlight how it is ultimately the terrain of the individual that influences whether one experiences disease. If we were to cut out the indoctrinated dogma, it becomes very clear that there is no need to even entertain germs as being a part of the equation based upon the admittances made within their respective papers.

The first paper I am presenting here was written by Dr. Gordon T. Stewart in 1968. At the time he wrote the paper, Dr. Stewart was a professor of Epidemiology and Pathology at the University of North Carolina. According to his Wikipedia page, the Scottish epidemiologist began his career as a professor of pathology and bacteriology at the University of Karachi in 1952. He would go on to become the Henry Mechan Professor of Public Health at the University of Glasgow from 1972 to 1984. Thus, we can see that Dr. Stewart has a very illustrious background.

However, there were strikes against Dr. Stewart for not always toeing the company line. He was against vaccines, and he was a particularly outspoken critic of the pertussis vaccination program. He would later be labeled an HIV “dissident to a degree” after having served on the board of Thabo Mbeki's presidential advisory panel on AIDS in 2000, even though Dr. Stewart also served as a World Health Organization adviser on AIDS beginning in the 1980s. In 1997, Dr. Stewart co-authored an article with Eleni Papadopulos-Eleopulos and Val Turner of the Perth Group in the journal Current Medical Research and Opinion questioning the HIV antibody tests. In this paper, they concluded that valid scientific methods must be utilized “in order to prove whether the ‘HIV’ proteins and antibodies arise as the result of a new, unique, exogenously acquired retrovirus.” They argued that until this was done, a positive “HIV” antibody test “may be used only as a marker for the presence or the development of AIDS.” They argued that there was no scientific basis for using antibody tests to prove HIV infection. While the Perth Group argued against the existence of HIV, Gordon himself was a proponent of Peter Duesberg's harmless “retrovirus” theory. In his own 1994 paper Scientific Surveillance and the Control of AIDS: A Call for Open Debate, Gordon stated that, with HIV, “there was no logical or scientific proof that it was the cause of AIDS, or even that it was pathogenic, except the indirect evidence that antibodies to it (seropositives) were found in many cases of AIDS and persons in risk-groups.” He told The Guardian in 2000:

"We have been criminally irresponsible - we have told people they have AIDS when they are HIV positive and that's not true. We have told them there is no cure and no vaccine and they are going to die. We have caused endless stress and even suicide. Families have worried about whether their children are going to be infected. That's why it is such a panic disease. The medical establishment has made the panic."

Thus, it is clear that, while Dr. Stewart believed in germ “theory” and virology, he was also not someone who was fully on board with the entire program, going so far as to question the pathogenicity of HIV, the tests used to detect the “virus,” and the hypothesis that HIV would lead to AIDS. He even served on the board of the Rethinking AIDS group until he passed away at the age of 97 in October of 2016.

Getting back to Dr. Stewart's 1968 paper, it shows the beginnings of a man going against the grain and challenging the germ “theory” dogma. As the paper itself is rather long, I am providing a few relevant excerpts where Dr. Stewart pointed out the limitations in the “theory.” From the very beginning, Dr. Stewart went after the germ “theory” of disease, stating that it is a gross oversimplification that does not explain the exceptions and anomalies that are present. He criticized the “theory” for becoming a dogma, i.e. a belief or opinion laid down by an authority as incontrovertibly true without question. Dr. Gordon felt that, if the “theory” was accepted uncritically, it would become a dogma that was captive of its own postulates. Echoing terrain theory elements, he stated that the germ “theory” became a dogma because it neglected the many factors which play a part in deciding whether the host/germ/environment complex will lead to “infection” and disease. Dr. Stewart stated that the unconditional assertion that “infectious” disease is primarily caused by microorganisms which are transmissible from one host to another is what led to the creation of the germ dogma. As the germ “theory” did not provide for exceptions and could not convincingly explain anomalies, and it was never reworked in light of new knowledge and information regarding “infectious” disease, the germ “theory” had officially become an unquestionable dogma.

Limitations of the Germ Theory

G. T. Stewart

M.D., B.Sc. Glasg., F.C.Path.

Professor of Epidemiology and Pathology, Schools of Public Health and Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A.

Summary

“The germ theory of disease—infectious disease is primarily caused by transmission of an organism from one host to another—is a gross oversimplification. It accords with the basic facts that infection without an organism is impossible and that transmissible organisms can cause disease; but it does not explain the exceptions and anomalies. The germ theory has become a dogma because it neglects the many other factors which have a part to play in deciding whether the host/germ/environment complex is to lead to infection. Among these are susceptibility, genetic constitution, behaviour, and socioeconomic determinants.

INTRODUCTION

Dogmas are comfortable things which, like favourite armchairs, increase in appeal as time passes. If accepted uncritically, any theory tends to become a dogma, that is to say, it becomes the captive of its own postulates. The more rigid the postulates, the more complete the captivity. The germ theory of disease is a dogma in so far as it asserts unconditionally that infectious disease is primarily caused by microorganisms which are transmissible from one host to another. The dogma lies in the generalisation and the elaboration of postulates; the basic fact, that transmissible microorganisms can cause disease, has been proved again and again. But a theory, to be valid as a continuing vehicle for thought, must provide for exceptions, must convincingly explain anomalies, must have embodied in its fabrication a recognition of its limitation as well as of its extent. A theory lacking in these qualities is vulnerable at any point to disproof; one which seeks to maintain validity in the face of anomalies or in contradiction to new facts, becomes a dogma. Because it has never been restated in the light of further knowledge and, indeed, self-evident truths about infectious disease, the germ theory must now be classed as a dogma.”

Later in his paper, it can be seen how Dr. Stewart began to lean towards a terrain approach, stating that the conditions for “transmission and reception and spread” needed to be favorable to the microbe in order for it to cause disease. He pointed out that the ability for microbes to communicate disease varied with inoculum size, donor and recipient, and with many environmental conditions. This is a fundamental difference between the two approaches, as germ “theory” sees these microbes as outside (exogenous) invaders that enter our bodies through “infection” that can cause disease, while the terrain perspective sees that the microbes are always present as they are a part of us (endogenous) and are only activated in order to respond to the conditions within our bodies in order to help us to heal. Dr. Stewart was agreeing with the terrain perspective in that it is the terrain that is the most important factor in activating microbes to do their job. The main area of contention seemed to be whether the microbes are a part of us, whether or not the process was detrimental or a part of healing, and whether the microbes and disease can be spread between hosts.

Dr. Stewart admitted that many microbes were regarded as pathogens without ever satisfying Koch's Postulates. He attempted to define what a pathogen is, stating that if the definition is that it is a microbe capable of causing disease, this would require the inclusion of many that are harmless. If a pathogen meant that the microbe always causes disease, few if any could be included as he admitted that most “disease-producing” organisms can be isolated from healthy persons. This is a clear violation of Koch's first Postulate which stipulates that the pathogen should not be found in those who are healthy.

Dr. Stewart sought an explanation of disease in factors outside the germ such as in attributes of the host, the community to which he belongs, and the environment in which he lives. He stated that few species of organisms inoculated directly into the body invariably cause “infection.” Unfortunately, rather than seeing that these facts falsified the germ hypothesis, Dr. Stewart felt that the germ was the starting point of “infection” even though it was not an exclusive or even principal cause of disease. He pointed out that an organism can be present in the respiratory or alimentary tracts without causing disease and that recovery can occur, spontaneously or under therapy, without the organism having been eliminated. Had Dr. Stewart taken it a step further at that time, he would have realized that this proved that the presence of a germ was an unnecessary factor in disease and recovery.

COMMUNICABILITY AND SPREAD OF INFECTION

“Under these headings the case for the germ is superficially incontrovertible; practically all infections from the common cold to smallpox are communicable if conditions for transmission and reception and spread are favourable to the microbe. But, as anyone who has tried to trace or transmit natural infection knows, communicability varies with inoculum size, donor and recipient, and with many environmental conditions.”

“The chain of events begins with a germ, usually described in terms which may or may not fulfil Koch’s postulates as a pathogen to distinguish it from all other microorganisms. But what is a pathogen? If it is defined etymologically as any microbe capable of causing disease, a range of organisms which are habitually harmless has to be included; if at the other extreme, the definition is restricted to those microbes which invariably cause disease and are never harmless, few if any can qualify since most disease-producing organisms can be isolated at times from healthy persons. The true definition must therefore provide for a chance or conditional element (P and y) and all pathogens are to that extent facultative. The higher the value of y and the lower the value of P, the more must the explanation of disease be sought in factors outside the germ-i.e., in attributes of the host, the community to which he belongs, and the environment in which he lives. Even highly communicable organisms, such as influenza and smallpox viruses, Pasteurella pestis, and Vibrio cholerae seldom produce 100% attack-rates as judged by morbidity. Indeed, few species of organisms inoculated directly into the body invariably cause infection as do venereal disease and vaccination, and even then the pattern of response varies considerably.

The Efficacy of Antimicrobial Measures

This provides indisputable proof that the germ is the starting point of infection but not that it is an exclusive or even principal cause of disease.”

“Disappearance of the organism during natural recovery ("wo die Krankheit zum Stillsand kommt") was used by Koch as a corollary to his first postulate; but, just as an organism can be present in the respiratory or alimentary tracts without causing disease, so also recovery can occur, spontaneously or under therapy, without the organism being eliminated. Cure, like resistance, depends upon the balance of power.”

While Dr. Stewart had made some revelations that should have led him to conclude that the germ hypothesis had falsified itself, he ultimately concluded that germs causing disease was an “established fact.” However, he was adamant that disease is not necessarily produced by access of the germ. Dr. Stewart provided that age, sex, genetic homogeneity, inoculum, contact, nutrition, and numerous other factors had to be taken into consideration as determinants of disease. While he included the germ as well, this could have been easily subtracted from the equation as he had shown that the evidence for germs as a causative factor amounted to nothing more than weak attempts to prove causation via correlations.

CONCLUSIONS

“My purpose has not been to discount the established fact that germs can cause disease. Indeed, infection without a germ would be as impossible, or miraculous, as conception without a sperm. But, just as pregnancy cannot be guaranteed by insemination, so disease is not necessarily produced by access of the germ. It is possible to assign to different microorganisms different levels of infectivity more or less in accordance with Theobald Smith’s equation and with standard dose-response relationships but only when dependent variables such as age, sex, genetic homogeneity, inoculum, contact, nutrition, and numerous other factors are rigidly standardised. This is possible only under experimental conditions and the outcome is progressively predictable as these conditions, one by one, are rigidly standardised. The variability of natural infections is proof that these conditions cannot be met and therefore that the conditions themselves are determinants, along with the germ, in causing infectious disease.”

It seemed clear that, even as far back as 1968, Dr. Stewart accepted that the terrain was the most important factor as to what decided the status of one's health. Everything that he stated about the factors leading to disease remains true without microbes being involved as a causative agent at all. As he would later go on to challenge vaccines and the HIV = AIDS hypothesis, it leads me to wonder whether Dr. Stewart had privately renounced the germ “theory” in favor of the terrain approach but was unwilling to take the position publicly for fear of further retaliation from the scientific community. Regardless, it is sadly a realistic fear that those in the field must contend with when deciding whether or not to speak out on what they truly believe in or be cut off from work and funding while dealing with public smear campaigns for doing so.

The next paper that challenged the germ “theory” dogma was written by prominent French-born American microbiologist Rene Dubos in 1955. Dubos is known for his pioneering work in isolating antibacterial substances from certain soil microorganisms which led to the creation of antibiotics. According to the Britannica, Dubos was a Rockefeller man as he joined the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City in 1927, where he spent most of his career, becoming a professor in 1957 and professor emeritus in 1971.

However, even though he was firmly ingrained in the ways of the Rockefeller medicine men, Dubos eventually questioned the orthodox approach of the germ “theory,” observing that "microbial disease is the exception rather than the rule.” He questioned why pathogens so often failed to cause disease after they became established in the tissues. Dubos grew critical of and questioned the use of antibiotics and other chemotherapies. He stressed that a drug's effect is “determined not only by its action on the parasite but also by the conditions prevailing in the body of the host.” He had found that environmental influences such as diet, toxins, climate, crowding and pesticides affected susceptibility to “infection” and to disease. According to a 1989 Rockefeller profile paper on Dubos, it is stated that Dubos's “revisions in the germ theory implicated the total environment as a determinant of disease.” Through his research, he showed that a microbe was “necessary” but not sufficient to cause disease. Dubos felt that men can coexist with microbes, and that “disease-producing” microbes are not inherently destructive and can persist in the body for long periods. Dubos ultimately determined that the important element in disease is not “infection” but rather “any stress that alters resistance, provokes the onslaught of illness, and then determines the outcome of the disease.” Thus, once again, the principles of the terrain and the conditions of ones internal environment are the main determinants of a diseased state, not the presence of a microbe.

Presented below is the entirety of Dubos’ 1955 paper spotlighting his second thoughts of the germ “theory” of disease. You will immediately see Dubos question why, even though everyone harbors germs said to cause disease, not everyone gets sick. This led him to the conclusion that germs are less important than environmental factors when it comes to affecting the health of the host. Like Dr. Stewart after him, Dubos stated that the germ “theory” was a simple concept that was so oversimplified that it rarely fit the facts of disease. He likened it to “a cult-generated by a few miracles, undisturbed by inconsistencies and not too exacting about evidence.” Dubos lamented that historians were biased in favor of the germ “theory,” and that they barely mentioned any arguments put forward by the physicians and hygienists who pointed out that clinical observations could not be completely explained by equating microbes with the causation of disease. Arguments against the work of Pasteur and Koch stressed that healthy humans and animals were often found to be harboring so-called pathogenic bacteria. Those who would fall victim to disease were most commonly those debilitated by other physiological disturbances. Thus, we can once again see that the “pathogenic microbes” failed Koch's first Postulate as they were found within healthy hosts, and that those who succumbed to disease were afflicted with other conditions.

Second Thoughts on the Germ Theory

Everyone harbors disease germs, yet not everyone is sick. This is ascribed to "resistance," suggesting that germs are less important in disease than other factors affecting the condition of the host

The germ theory of disease has a quality of obviousness and lucidity which makes it equally satisfying to a schoolboy and to a trained physician. A virulent microbe reaches a susceptible host, multiplies in its tissues and thereby causes symptoms, lesions and at times death. What concept could be more reasonable and easier to grasp? In reality, however, this view of the relation between patient and microbe is so oversimplified that it rarely fits the facts of disease. Indeed, it corresponds almost to a cult-generated by a few miracles, undisturbed by inconsistencies and not too exacting about evidence.

Historians usually give a biased account of the heated controversy that preceded the triumph of the germ theory of disease in the 1870s. They barely mention the arguments of those physicians and hygienists who held that clinical observations could not be completely explained by equating microbe with causation of disease. The critics of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch pointed out that healthy men or animals were often found to be harboring virulent bacteria, and that the persons who fell victim to microbial disease were most commonly those debilitated by physiological disturbances. Was it not possible, they argued, that the bacteria were only the secondary cause of disease-opportunistic invaders of tissues already weakened by crumbling defenses?

Dubos went on to present a 1954 case of a lacquer sprayer who sued his employer for his development of pneumonia and pleurisy due to the cold, damp, and drafty conditions that he was subjected to at work. The judge agreed that the environmental conditions had led to disease and awarded the employee damages. Dubos then assumed that the employee had been “infected” at some point, and that the environmental conditions caused the microbe to bring about disease. However, as pointed out afterwards with a quote by George Bernard Shaw, the invention of an imaginary “infection” from a microbe is unnecessary as the “microbe of a disease might be a symptom instead of a cause."

Dubos presented another case at about the same time involving rabbits that were intentionally “infected” with a “virus” by a doctor who wanted to rid them from his estate. This “virus” was said to spread and cause disease amongst the rabbits in the population, and as no climatic or physiological cause was blamed, the germ “theory” was “vindicated.” Despite presenting stories throughout history that seemed to corroborate his own belief in germ “theory,” Dubos went back to the inability to explain the pneumonia case. He stated that theories of disease “must account for the surprising fact that, in any community, a large percentage of healthy and normal individuals continually harbor potentially pathogenic microbes without suffering any symptoms or lesions.” Dubos felt that this was a wide phenomenon, not only in humans and animals, but also plants and microscopic cells.

It is entertaining to note that this doctrine was recently revived in an English court of justice. According to an account published in The Lancet of November 6, 1954, a lacquer sprayer, aged 36, sued his employers on the ground that he had contracted pneumonia and pleurisy because the spraying room in which he had worked was cold and drafty. His lordship the judge found that the plaintiff's work place was indeed cold, drafty and damp in the early morning. He accordingly awarded damages totaling 401 pounds, feeling satisfied that the plaintiff's illness was caused by the absence of heating. There is little doubt that the pneumonia and pleurisy of which the workman complained were manifestations of the activities of some microbial agent-virus or bacterium or probably both. Furthermore, it is probable that the workman had not contracted infection in the shop but had been harboring the guilty microbes in his organs for weeks, months or perhaps even years. The ruling that the deficient heating had caused the pneumonia brings to mind the view expressed by George Bernard Shaw in the preface to The Doctor's Dilemma: "The characteristic microbe of a disease might be a symptom instead of a cause."

Fortunately for the prestige of the germ theory, another case involving a microbial disease was being tried at the same time before a French court. Readers of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN will recall that the myxomatosis virus, which has killed off immense numbers of rabbits in Australia, was recently introduced in France by a doctor who wished to get rid of the rabbits on his estate, and that the disease soon spread over most of Western Europe [see "The Rabbit Plague," by Frank Fenner; February, 1954]. The too-enterprising French doctor was sued for huge sums of money by enraged hunters, fur dealers, rabbit breeders and others whose interests had been affected. The trial brought out many fine points of legal responsibility, but there was no doubt in anyone's mind that the myxomatosis virus-not some climatic or physiological factor-was the cause of the destruction of rabbits. The germ theory had been vindicated.

History offers many examples which, like myxomatosis, illustrate the operation of the germ theory of disease in its simplest and most direct form. The epidemic that ravaged Athens during the Peloponnesian War has not been convincingly identified, but Thucydides' vivid description makes clear its immensely destructive power. According to Edward Gibbon, the Justinian plague killed most of the European population during the 6th century, and plague reappeared with the same virulence in Western Europe under the name of "The Black Death" in the 14th century. Other illustrations could be selected from more recent historical events: the immense mortality caused by smallpox among the American Indians when they came into contact with the disease, introduced first accidentally, then willfully, by the European invaders; the decimating effect of measles in the Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands in 1775, in the Fiji Islands a century later and among the Columbia River Indians in 1830; the death from tuberculosis of some 90 percent of the Indians of the Qu' Appelle Valley in Western Canada within a decade. These instances, selected at random, provide tragic evidence that a microbial agent may strike down the weak and the healthy alike when newly introduced in a susceptible population.

Yet what shall we say of the case of pneumonia that came before the English court? There are many situations in which the microbe is a constant and ubiquitous component of the environment but causes disease only when some weakening of the patient by another factor allows infection to proceed unrestrained, at least for a while. Theories of disease must account for the surprising fact that, in any community, a large percentage of healthy and normal individuals continually harbor potentially pathogenic microbes without suffering any symptoms or lesions. This type of dormant infection seems to occur widely, not only among men and animals, but also probably among plants and even microscopic cells. Only a few examples need be quoted to illustrate the theoretical interest and practical importance of the phenomenon.

Dubos assumed that all healthy mice used for medical research harbored many “viruses” capable of causing severe disease and death. These “viruses” could be “evoked” by dropping certain sterile fluids in their nasal cavities. He also noted that pseudotuberculosis could be evoked in mice via subjecting the animals to radiation, to certain nutritional deficiencies, or to a number of other stresses, thus highlighting once again that it is the environmental stressors that brings about disease, not any microbe. Dubos then carried this over to man, where he stated that those who are healthy carry throughout life a host of microbes “which can start proliferating and cause disease” under the influence of factors that are rarely, if ever, well understood. This aligns with terrain theory, which states that the microbes are not outside invaders, but are within us at all times, and that it is the condition of an individual’s terrain that calls the microbes forward in order to “put out the fire.” The microbes are not the cause of the fire. They are the solution to restore balance.

Dubos provided examples, stating that a large percentage of the readers of his article harbor “virulent” tubercle bacilli and staphylococci, but very few will ever become aware of the microbes' presence as it takes an intervening factor to cause the microbes to proliferate and cause disease. He also included the example of the herpes “virus,” where it is assumed that one is “infected” early in life. The “virus” then lays dormant until some outside factor, be it a fever of unrelated origin, excessive irradiation, certain types of surgery, menstruation, improper food, etc., brings about an episode of blisters. In other words, the germs are not necessary to explain disease as the body is responding to one or more provoking factors that are the true cause of disease.

All the healthy-looking mice raised for medical research under highly standardized and hygienic conditions carry a multiplicity of viruses capable of causing in them severe and often fatal pulmonary disease. Under normal circumstances the viruses remain dormant in the form of so-called "latent infections." But they can be "evoked," as the expression goes, by the simple artifice of dropping certain sterile fluids into the nasal cavity of the mouse. There is another disease, called pseudotuberculosis, which can be evoked in normal mice by subjecting the animals to radiation, to certain nutritional deficiencies or to a number of other stresses. Pseudotuberculosis results from the unrestrained multiplication of a diphtheria-type bacillus, which exists in a latent form in normal mouse tissues.

Like the mouse, normal man carries throughout life a host of microbes which now and then start proliferating and cause disease-under the influence of factors rarely if ever well understood. For example, a large percentage of the readers of this article harbor virulent tubercle bacilli and staphylococci, but very few will ever become aware of the microbes' presence. Most likely the infections will remain dormant unless brought into activity by some other intervening factor causing a "loss of general resistance"-an expression useful by virtue of its vagueness. Uncontrolled diabetes, life in a concentration camp, overwork, overindulgence, even an unhappy love affair, may precipitate an attack of disease, much as exposure to drafts and to damp air was judged by the English court to be the cause of pneumonia. An example familiar to most of us is provided by the benign but recurrent lesions known as fever blisters or cold sores, caused by the herpes virus. Many people contract the herpes infection early in life, and the virus persists somewhere in the tissues from then on. It lingers idly until some provoking stimulus causes it to manifest its presence in the form of blisters. The stimulus may be a fever of unrelated origin, excessive irradiation, certain types of surgery, menstruation or improper food. Thus the herpes virus is merely the agent of infection: the instigator of the disease is an unrelated disturbance of the host.

Dubos argued that bacteria and “viruses” were known to be “virulent” based upon the results of animal studies and the ability to easily produce experimental disease without outside factors. However, he failed to account for the fact that these experiments never reflect what would happen in nature with natural exposure routes, instead opting for inhumane and grotesque experiments involving the use of ground up diseased tissues and brains from humans and/or other animals with added chemicals/substances that are injected directly into the brain, eyes, muscles, skin, stomachs, testicles, etc., of an animal. Despite this, Dubos did admit that it had been repeatedly observed that vigorous treatment with drugs for any type of “virulent infection” in humans could bring about the paradoxical effect of ushering in another type of “infection.” He argued that we are entering into the era of man-made diseases brought about by the new therapeutic practices and procedures.

It has been easy to demonstrate experimentally that the tubercle bacillus, the staphylococcus and the herpes virus are capable of causing progressive disease and even death in animals without the apparent participation of other contributory factors. For this reason these microbes are said to be virulent. But there are many other types of microbes not regarded as virulent which also can play an important part in the causation of disease under special circumstances. C. P. Miller of the University of Chicago School of Medicine has shown, for example, that some of the manifestations of radiation sickness are due to invasion of the blood and certain organs by bacteria normally present in the intestinal tract; indeed, he succeeded in protecting experimental animals from radiation death by controlling this infection of intestinal origin with antimicrobial drugs. In contrast, it has been repeatedly observed that vigorous treatment with drugs of almost any type of virulent infection in a human being may have the paradoxical effect of bringing about another type of infection, caused by the proliferation of otherwise innocuous fungi and bacteria. We are beginning, in fact, to witness the appearance of man-made diseases, caused by the rapid changes in human ecology brought about by the new therapeutic procedures.

Dubos noted that the doctrines of “immunology” could not offer any explanation for why these supposedly pathogenic and virulent microbes and “viruses” go dormant. What causes the “immune” system to ignore these agents supposedly capable of causing disease? He also stated that the nutritional status of an individual is a factor that determines disease, noting that famine and pestilence go together throughout history. Dubos brought up the example of diabetics and how those receiving insulin injections were able to “fight off” bacteria as well as normal people are capable of doing. He stated that it was “tempting to postulate that the biochemical abnormalities brought about by uncontrolled diabetes create an environment favorable for the activities of the bacteria,” once again highlighting the internal terrain as the most important factor that leads to the proliferation of bacteria as they attempt to restore homeostasis. It was clear to Dubos that susceptibility to “infection” was “not necessarily inherent in the tissues, or dependent on the presence of antibodies,” but that it was the “temporary expression of a physiological disturbance,” i.e. the result of some environmental factor. He called for a reworking of the germ “theory” to account for factors such as:

“Pathogenic” agents persisting in the tissues without causing disease.

“Pathogenic” agents causing disease even in the presence of “specific” antibodies.

“Nonpathogenic” agents proliferating in an unrestrained manner when the body's normal physiology is upset.

If he had been intellectually honest enough, Dubos would have realized that the germ “theory” did not need reworking but, rather, discarding, as these contradictions not only falsify the hypothesis, but they are easily explained by the terrain perspective.

The classical doctrines of immunity throw no light on precisely what mechanisms determine whether dormant microbes will remain inactive or begin to act up. What is needed to analyze this problem is some understanding of the agencies responsible for natural resistance to infection, and of the factors that interfere with the operation of these agencies. Fortunately interest in this area of research is increasing rapidly. Several independent trends of thought appear clearly in current programs of investigation.

One approach is a search of normal animal tissues for substances possessing antimicrobial activity. There are many such substances. One of the best known is lysozyme, discovered some 30 years ago by the late Alexander Fleming of penicillin fame. But the difficulty is not to discover antimicrobial substances; it is rather to gain information as to what role, if any, they play in the body's resistance to infection. The most interesting information on this point has come from studies at Western Reserve University Medical School by a group of immunologists under the leadership of Louis Pillemer. They have separated from human and animal sera a peculiar protein, "properdin," which can destroy or inactivate a few types of bacteria and viruses under certain conditions in the test tube. They have established, furthermore, that the concentration of properdin in serum is not constant. Particularly exciting is the finding that when animals are exposed to weakening radiation, properdin disappears almost completely within four to six days, precisely at the time when the animals become highly susceptible to the bacteria normally present in their intestinal tract.

Another determinant of susceptibility and resistance is the individual's nutritional state. History shows that famine and pestilence commonly ride together, but the links that bind them are neither obvious nor simple. This has been well demonstrated by a thoughtful analysis carried out by Howard Schneider at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. I should like to cite the effect of diabetes, a metabolic disorder. It has long been known that patients with uncontrolled diabetes are extremely susceptible to certain bacteria, notably staphylococci and tubercle bacilli, whereas diabetics receiving proper insulin treatment are just as resistant to these bacteria as are normal individuals. In other words, susceptibility to infection in these cases appears to be linked in a reversible manner to the metabolic state. It is tempting to postulate that the biochemical abnormalities brought about by uncontrolled diabetes create an environment favorable for the activities of the bacteria. In fact, experiments carried out at Bryn Mawr College and at the U. S. Air Force School of Aviation Medicine by J. Berry and R. B. Mitchell, and in our own laboratory at the Rockefeller Institute, have shown that one can increase the susceptibility of mice to microbial disease by metabolic manipulations as simple as temporary deprivation of food, or feeding an unbalanced diet rich in citrate. Furthermore, resistance can be brought back to normal within two to three days by correcting the nutritional disorder.

It is clear, therefore, that susceptibility to infection is not necesarily inherent in the tissues, or dependent on the presence of antibodies, but is often the temporary expression of some physiological disturbance.

All in all, a new look at the biological formulation of the germ theory seems warranted. We need to account for the peculiar fact that pathogenic agents sometimes can persist in the tissues without causing disease and at other times can cause disease even in the presence of specific antibodies. We need also to explain why microbes supposed to be nonpathogenic often start proliferating in an unrestrained manner if the body's normal physiology is upset.

Dubos felt that it was surprising that microbial disease is the exception rather than the rule, especially as we continually come into contact with all sorts of microbes. He pondered why all microbes are not capable of causing disease. He felt that humans are endowed with a high degree of natural resistance to the microbes normally present in the environment as we have been able to survive and flourish despite the presence of microbes everywhere. Dubos noted that there must be balance, and anything that upsets that balance, such as irradiation, metabolic abnormalities, treatment with antimicrobial drugs, psycho-social factors, etc. will invariably lead to disease. He further added that the first phase of the germ “theory” stated that “virulence” was regarded as lying solely within the microbes themselves. However, it was becoming clear that “virulence” was ecological instead. While he argued that there was evidence otherwise, and that all common microbes already present and ordinarily harmless are capable of producing disease when physiological circumstances are sufficiently disturbed, it is clear that no outside invading microbe or “virus” is necessary as an explanation for disease. It is the environmental factors and the terrain of the individual that dictates disease.

To guide one's thinking on these problems it is well to keep in mind a fact so simple that it is never talked about-namely, that the tissues of man and animals contain everything required for the life of most microbes. This is well shown by the ability of tissue cells to support the growth of bacteria and viruses in the test tube. It is therefore surprising that microbial disease is the exception rather than the rule, for we continually come into contact with all kinds of microbes. The problem, in other words, is not merely, "How do some microbes cause disease?" but rather, "Why are not all microbes capable of causing disease?"

We have already cited evidences of the tendency for a new kind of microbe to run riot in a population exposed to it for the first time. Even more striking in this regard are the observations made by James Reyniers and his colleagues at the University of Notre Dame. They found that animals born and raised in a sterile environment died when they were exposed to common bacteria such as are always present in a normal environment. For example, some of the banal microorganisms present in ordinary food products were virulent for them.

Thus the simple fact that a population survives and flourishes in a given environment implies that its members are endowed with a high degree of natural resistance to the microbes normally present in that environment. This natural resistance stems in part from evolutionary selection of the strains best endowed with mechanisms for withstanding the infections, and probably in part from the development of adaptive reactions in response to early exposure to the microbes. We cannot discuss here the workings-still very obscure-of these various protective mechanisms. Suffice it to say that their over-all effect is the establishment of a state of biological equilibrium between man or animals on the one hand, and the microbes endemic in the community on the other.

Whatever their nature, the mechanisms responsible for natural resistance are in general most effective under the narrow range of conditions constituting the "normal" environment in which the population has evolved. Any shift from the normal is likely to render the equilibrium unstable. I have already mentioned examples of disturbances that may upset the equilibrium-irradiation, metabolic abnormalities, treatment with antimicrobial drugs and so on. Psycho-social factors could have illustrated the point just as well. Although the precise mode of these factors is still unknown, there is no reason to doubt that they act by changing the environment, especially the milieu intel'ieul', in which higher organisms and microbes have evolved to a state of biological equilibrium.

During the first phase of the germ theory the property of virulence was regarded as lying solely within the microbes themselves. Now virulence is coming to be thought of as ecological. Whether man lives in equilibrium with microbes or becomes their victim depends upon the circumstances under which he encounters them. This ecological concept is not merely an intellectual game; it is essential to a proper formulation of the problem of microbial diseases and even to their control.

To be sure, there are situations where a microbe itself is a sufficient cause of disease irrespective of the physiological state of the exposed individual. Infancy exemplifies one such situation. The child, arriving so to speak as an immigrant in the human herd, comes into contact with certain microbes which are not yet fully integrated in human life by evolutionary forces and with which he as an individual has not had any experience. We have noted another type of situation where people may be defenseless against the disease agent: namely, the introduction of a new microbe in a previously unexposed population. This type of relationship is certainly in the mind of all scientists concerned with bacteriological warfare. Untold harm might follow the introduction of types of infectious agents to which we have never been exposed as a group in the past. Our farm animals or our crops would prove equally susceptible to plagues and pests so far kept at bay by unending vigilance.

However, dramatic as these special cases of complete lack of resistance may be, they do not constitute the main problem of microbial disease in ordinary life. As we have seen, practically all the common microbes already present, though ordinarily harmless, are capable of producing disease when physiological circumstances are sufficiently disturbed. These ubiquitous microbes rarely cause death, but they are certainly responsible for many ill-defined ailments-minor or severe-which constitute a large part of the miseries and "dis-ease" of everyday life. They establish a bridge between communicable and noncommunicable disease-a zone where presence of the microbe is the prerequisite but not the determinant of disease, a situation in which the fact of infection is less decisive in shaping the course of events than the physiological climate of the invaded body. For reasons that cannot be discussed here, it is unlikely that antimicrobial drugs can control this aspect of the relationship between man and microbe. What is most needed at the present time is some knowledge of the physiological and biochemical determinants of microbial diseases. For we cannot possibly hope to eliminate all the microbes that are potentially capable of causing harm to us. Most of them are an inescapable part of our environment.

The views of those who still deny the microbial causation of disease altogether are epitomized in a saying they are fond of repeating: "If the germ theory of disease were correct, there would be none on earth to believe it." I have attempted to show that this statement implies a narrow and incomplete understanding of the germ theory. Much more perceptive-indeed prophetic-was the conclusion reached by John Caius in his essay on the English "sweating sickness " in 1552: "Our bodies cannot...be hurt by corrupt and infective causes, except ther be in them a certein mater apt...to receive it, els if one were sick, al shuld be sick."

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24944640

Dubos understood that we cannot possibly hope to eliminate all the microbes that were thought to cause disease as microbes are ubiquitous within us and within nature. He highlighted many damning problems with germ “theory,” noting that the microbes thought to be pathogenic regularly are shown not to be. These “pathogenic agents” are often found in the healthy, and they are present at times even when “antibodies” are said to be circulating. He even noted that “non-pathogenic” bacteria will proliferate during times of disease. These critical points line up with Dr. Stewart's observations that “pathogenic” microbes are often present when no disease occurs, and they can remain within the host despite treatment and/or spontaneous cessation of the disease.

Both men understood that the terrain of the individual, heavily influenced by factors such as improper nutrition, stressors, environmental conditions, radiation poisoning, toxicity from pharmaceuticals and vaccines, etc., can lead to disease within the body. While they still believed that germs had a role in disease, both men downplayed this role to the extent that the microbes were almost insignificant factors. Germs were present but needed to be “activated” in order to cause disease. Microbes were considered “necessary” but not sufficient to cause disease by themselves. In other words, the microbes could not create disease without help. This “help” was said to come from the various factors that influence the terrain of the individual. As these factors are both necessary and sufficient to cause disease, there is no reason to ever entertain the disproven hypothesis that it is the germs that cause disease. Germs are unnecessary and insufficient, with no scientific evidence supporting these agents as a cause of disease. Had Dr. Stewart and Mr. Dubos truly understood the lack of scientific evidence supporting pathogenic germs, I believe that they would have ultimately come around to the same conclusion that Rudolf Virchow, the father of modern pathology, did when he stated:

"If I could live my life over again, I would devote it to proving that germs seek their natural habitat: diseased tissue, rather than being the cause of diseased tissue.”

-Rudolf Virchow

Please investigate the variable "E-Cigarettes.”

🚨🚨ONE OF THE BIGGEST BOMBSHELLS 🚨🚨

https://manuherold.substack.com/p/bombshell-the-recent-uptick-in-vaping

I found this book related to the Terrain theory on disease: https://openlibrary.org/works/OL6900886W/Toxemia_the_basic_cause_of_disease?edition=toxemiabasiccaus00til_8cb

It was written by Dr. John Henry Tilden of the American Society of Natural Hygiene. Most of improvement to public health came from the early Hygienists and the popular Hygiene movement that pushed from removing sewage and garbage from littering the streets.