In 1877, German bacteriologist Robert Koch formulated a series of logical criteria that he felt were the necessary requirements that must be satisfied in order to establish a microorganism as the causative agent of disease. These steps were formally published in 1890, and are as follows:

The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms suffering from the disease, but should not be found in healthy organisms.

The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture.

The cultured microorganism should cause disease when introduced into a healthy organism.

The microorganism must be reisolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

In 1952, Lester S. King, a Harvard educated medical doctor who wrote many books on the history and philosophy of medicine, wrote a paper examining the importance of Koch's Postulates. King stated that Koch forged a chain of evidence connecting a specific bacterium and a given disease that was so strong and so convincing, that his postulates were considered a model for all future work:

Dr. Koch's Postulates

“What Koch accomplished, in brief, was to demonstrate for the first time in any human disease a strict relation between a microorganism and a disease. Recovery of a bacterium is not enough, since in tuberculosis, for example, other workers, as mentioned above, had identified bacteria. Nor is transmission of the disease enough. Transmission merely indicates an infectious nature, and the infectious nature of tuberculosis was already fairly well established. Koch's contribution was in forging a chain of evidence which connected a specific bacterium and a given disease. So strong was this chain, so convincing the demonstration, that his principles have been exalted as "postulates" and considered a model for all future work.”

https://academic.oup.com/jhmas/article-abstract/VII/4/350/784475

For two centuries, these postulates (i.e. to suggest or accept that a theory or idea is true as a starting point for reasoning or discussion) have stood as the “gold standard” for establishing the microbiological etiology of infectious disease. The Merriam-Webster definition defines these steps as required to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. In 2003, the WHO stated that conclusive identification of a causative microbe of disease must meet all of the criteria as laid forth by Koch. A 1996 paper by D.N. Fredericks et al. stated that Koch created a scientific standard for causal evidence. Virologist Vincent Racaniello said that Koch's Postulates placed the study of infectious disease on “a secure scientific foundation.” Virologist Ron Fouchier confirmed that isolating a microorganism does not mean that it is the causative agent, and that in order to show that it causes disease, one needs to fulfill Koch’s Postulates. These postulates are so essential that, according to a 2015 paper by Ross and Woodyard, they are “mentioned in nearly all beginning microbiology textbooks” and “continue to be viewed as an important standard for establishing causal relationships in biomedicine.”

However, since their inception, the postulates have become rather divisive, leading to the very same people that praise them as essential to also attempt to tear the postulates down and/or revise them. Going back to D.N. Fredericks et al. who had praised Koch's Postulates for setting the scientific standard, the authors later stated that “the limitations of Koch's postulates, evident in the 1800s, are even more pronounced today.” They then reworked the postulates into a series of 7 steps. Vincent Racaniello, who had stated that the postulates established a secure scientific foundation, later added that they had “severe limitations” which were more obvious for “viral” disease. He then countered that the application of nucleic acid-based methods of microbial identification made Koch’s Postulates even less applicable. Ron Fouchier, who said that the postulates must be fulfilled to prove a microbe causes disease, incorrectly claimed to have fulfilled Koch's Postulates for “SARS-COV-1,” by attempting to instead satisfy Thomas Rivers watered-down revision of the postulates from 1937. There have been many other attempts to rework Koch's Postulates in order to make them more favorable for researchers to try and establish a cause-and-effect relationship, such as those set forth by Robert Huebner in 1957 as well as the 1965 criteria by Bradford Hill. A 1976 paper by Alfred S. Evans looked at many of these attempted revisions and stated that, due to asymptomatic carriers and differences in host responses, the original postulates were “simplistic” and not in accord with the current “facts.” Evans argued that the “insistence on their fulfillment before causality is accepted with a new agent in relation to a disease should be abandoned.”

Thus, we must ask ourselves why the about face on what many sources state are the essential requirements that must be satisfied in order to establish the cause-and-effect relationship between microbes and disease? What happened that made researchers praise Koch's Postulates in one breath, and then try to rework and wiggle around the four logical criteria in another? The answers lie in Robert Koch's foray into Egypt and India in order to determine the causative agent of cholera. What transpired during his investigation was a nearly complete abandonment by Koch of his own logic in order to make his evidence fit his preconceived idea of a microbial cause of disease. Let's examine the moment that a man allowed the pressures of the discovery and the allure of fame and prestige to cloud his own rational thinking.

“The only possibility of providing a direct proof that comma bacilli cause cholera is by animal experiments. One should show that cholera can be generated experimentally by comma bacilli.”

-Robert Koch

Koch, R. (1987f). Lecture cholera question [1884]. In Essays of Robert Koch. Praeger.

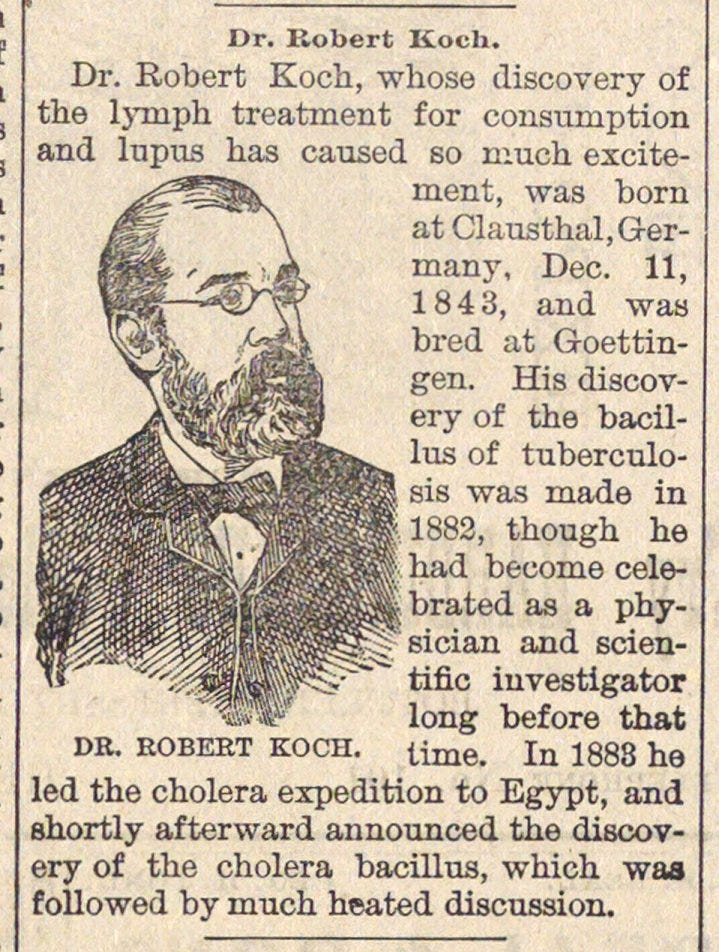

Whilst Robert Koch was in the midst of pursuing the cause of tuberculosis in the early 1880s, an epidemic of cholera broke out in Egypt in 1882. A French team had already been sent to investigate the epidemic in order to determine the responsible agent of the disease. Up to that time, cholera was believed to be caused by miasma, or “bad air” that arose from decaying organic matter. However, with the introduction of Louis Pasteur's germ theory of disease, a microbial agent was pursued instead. As Robert Koch was pioneering new ways to see and grow these bacteria, he was sent as part of a German team to investigate the matter. Koch went to work in Egypt convinced that the disease was an infectious one and that the etiological agent would be a bacterium. However, by the time he arrived in Egypt, the epidemic had mostly subsided. While he had begun to suspect a comma-shaped bacillus that he had found in the intestines of the victims after performing several postmortems on the deceased, Koch was unable to confirm his hypothesis that this bacillus was the responsible agent of disease. Koch ultimately left Egypt without answers.

However, as luck would have it, in 1883, another cholera epidemic broke out in India which led Koch to continue his pursuit of the causative agent there. Over the next year, he sent out regular updates to the press about his discoveries. On January 7th, 1884, Koch announced that he was able to grow the comma-shaped bacterium in pure culture, thus satisfying the second of his four postulates. On February 2nd, 1884, Koch announced that his comma-shaped bacterium was the causative agent of the disease known as cholera:

The greatest steps towards the discovery of Vibrio cholerae

“Koch and his colleagues Georg Gaffky and Bernhard Fischer carried out many post-mortems, finding a bacillus in the intestinal mucosa that was present only in the corpses of persons who died of cholera. He deduced that the bacillus was related to the cholera process, but he was not sure whether it was causal or consequential.

Late in 1883, Koch sailed to Calcutta, India, where the epidemic was still very active [21].

On 7 January 1884, Koch announced that he had successfully isolated the bacillus in pure culture: 1 month later, he added that the bacillus was ‘a little bent, like a comma’ [22].

He also noted that the bacillus was able to proliferate in moist soiled linen and damp earth, and was susceptible to drying and weak acid solutions. On 2 February 1884, Koch reported from Calcutta to the German Secretary of State for the Interior his reasoned conviction that the vibrion found in the intestines and stools of cholera victims was the causal agent of the disease. This was the sixth of seven step-by-step dispatches sent over a period of 24 weeks that provided a description of research in progress, and that were made available to the German press as they were received [23].”

https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198-743X(14)60855-7/fulltext

By February of 1884, Robert Koch was claiming the discovery of the causative agent of cholera based upon the satisfaction of the second of his four postulates. However, this leaves a very important question unanswered. What about the other postulates? Did Robert Koch actually satisfy the remaining three logical requirements in order to make such a proclamation? For more detail, we can turn to a paper written in 1984, marking the 100-year celebration of Koch's “landmark discovery.”

During his time in Egypt, Koch found numerous microbial agents in the stools samples of cholera victims. However, as none of these microbes were considered predominant over the others, Koch decided that none of the microbes could be the causative agent. When he examined the intestines and found his comma-shaped bacillus in those who died from cholera, but not in cases of other diarrheal diseases, Koch hypothesized that there must be a relationship. Koch felt that his hypothesis could only be resolved by isolating the bacillus, growing it in pure culture, and reproducing the cholera disease in animals. However, he was unable to obtain a pure culture at the time and his attempts to infect monkeys, dogs, mice, and hens with choleraic material were all unsuccessful. The French team that had arrived before Koch had also found the same bacillus and failed as well in transmitting the disease to guinea pigs, rabbits, mice, hens, pigeons, quails, pigs, a jay, a turkey, and a monkey.

When Koch announced on January 7th, 1884, that he had successfully grown the comma-shaped bacillus in pure culture, he began to rationalize in his mind that finding this bacillus exclusively in patients deemed to be cholera victims was satisfactory enough to prove a causal relationship as it might not be possible to reproduce a similar disease in animals. Thus, he had begun renouncing a core tenet of the proof that he had stated was essential four months prior to his January 1884 announcement. Koch was turning his back on his own logic and reasoning. By his 6th dispatch in February 1884, Koch stated that, while it would have been desirable to reproduce the disease in animals, this had proved impossible, thus cementing his break with his own logic:

Robert Koch and the cholera vibrio: a centenary

“Koch had originally started in Alexandria, where he arrived on 24 August 1883 as the leader of a German mission that included two other medical members, Georg Gaffky and Bernhard Fischer, and a technician, and his first dispatch was dated 17 September.' By this time the mission had made bacteriological investigations on 12 patients with cholera and carried out necropsies on 10 who had died of the disease. In the stools a multitude of different organisms had been found, none of which was preponderant. Conversely, necropsies showed the constant presence of a specific bacillus in the intestinal mucosa of subjects dying from cholera but not from other diarrhoeal diseases. Koch concluded that there could be no doubt that this bacillus stood in some relation to the cholera process, but whether the relation was causal or consequential remained to be determined. This question could be resolved, he stipulated, only by isolating the bacillus, growing it in pure culture, and reproducing a similar disease in animals. He had not yet obtained a pure culture, but attempts to infect monkeys, dogs, mice, and hens with choleraic material had proved fruitless.”

“By the time that Koch had arrived in Alexandria a French medical mission (Isidore Straus, Emile Roux, Edmond Nocard, and Louis Thuillier), financed by its government on the initiative of Pasteur, had already been there for nine days. It had carried out essentially the same investigations as the German mission, finding the bacillus that Koch was also to describe, and failing to infect guinea pigs, rabbits, mice, hens, pigeons, quails, pigs, a jay, a turkey, and a monkey.”

“In his fifth dispatch on 7 January 1884 Koch announced that he had successfully isolated the bacillus in pure culture. The necropsy findings had been the same as those in Egypt, and should it be possible, he argued, to confirm that the bacillus was to be found exclusively in patients with cholera, it would hardly be possible to doubt its causal relation to the disease-even though it might not be possible to reproduce a similar disease in animals. Here, Koch was renouncing one of the elements of proof that he had himself stipulated almost four months before in his first dispatch.”

It was in his sixth dispatch, dated 2 February, that Koch stated that the bacillus was not straight, like other bacilli, but "a little bent, like a comma" (ein wenig gekriimmt, einem Komma dhnlich).' Other properties of the bacillus were its ability to proliferate in moist soiled linen or damp earth and its pronounced susceptibility to drying and to weakly acid solutions. Koch then pointed out that the specific organisms were always found in patients with cholera but never in those with diarrhoea from other causes. In the early stages of cholera they were relatively rare in the evacuations, but as these progressed to become ''rice water stools" the bacilli were present in almost pure culture; in those patients who recovered, the bacilli gradually disappeared from the stools. Though, he added, it would have been desirable to reproduce the disease in animals, this had proved impossible. All the evidence suggested that, as with typhoid and leprosy, animals were not susceptible to the disease, and naturally infected animals were not to be found even in areas where cholera was endemic throughout the year.”

We can see that Koch clearly abandoned the idea of recreating cholera experimentally in animals, even with pure isolates. This is a requirement that he had stated was the only possibility of providing direct proof that comma bacilli cause cholera. Thus, it is not too surprising that many of his contemporaries were unimpressed with Koch's evidence. From the same paper, we find that Rudolf Virchow, considered the father of modern pathology, stated that absolute proof of Koch's thesis was lacking. The response in Germany was mixed, with Max Von Pettenkofer, the founder of the discipline of hygiene who was considered the greatest authority on cholera, felt that Koch's work was heresy. In France, the response was entirely negative, with an article claiming that the “great microbe hunter” had followed a completely false trail while asking if he would give back his “decorations” (i.e. fame and prestige). In Britain, Koch's theory was emphatically rejected when, in August 1884, a team of researchers consisting of Emanuel Klein, Heneage Gibbes, and a technician sailed for Calcutta to check Koch's findings. Upon doing so, they entirely repudiated his work. India appointed 13 esteemed physicians to consider their report, and 8 of these physicians endorsed the findings of Klein and Gibbs. One stated that Koch's investigations turned out to be “an unfortunate fiasco:”

“At the conference Koch was the principal speaker, and he outlined the work of the German mission, of which he was to publish, with Gaffky, the definitive account three years later. In the discussion Rudolf Virchow sounded a note of caution by pointing out that absolute proof of Koch's thesis was still lacking. As to the dynamics of the disease, Koch erroneously concluded that the cholera toxin not only acted on the intestinal epithelium but also exerted a paralytic action on the cardiovascular system.

In Germany the response to Koch's thesis was mixed, some supporting it while others-especially Pettenkofer and his followers-regarded it as little short of heresy. In France reactions-doubtless influenced by the conclusions of the French mission to Egypt-were almost entirely negative, a leading article in one medical journal declaring: "The great microbe hunter has followed a completely false trail. (Will he give back his decorations ?)." But the most emphatic rejection came from Britain. On 6 August 1884 a British mission consisting of Emanuel Klein, Heneage Gibbes, and a technician sailed for Calcutta to check Koch's findings. In their report they referred to Pettenkofer as "justly to be considered the greatest living authority on cholera" and not only flatly repudiated Koch's thesis but also dismissed the role of drinking water. To consider the report the Secretary of State for India appointed a committee of 13 distinguished physicians, eight of whom submitted memorandums endorsing the conclusions of Klein and Gibbes. One member, Sir William Gull, declared his conviction that "cholera as cholera does not produce cholera." Another, Sir John Burdon-Sanderson (as he later became), stated in a public lecture that Koch's investigations had been "an unfortunate fiasco."

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1444283/

We can get a bit more insight into Klein and Gibbes refutation of Koch's cholera hypothesis from the 1886 paper The Official Refutation of Dr. Robert Koch’s Theory of Cholera and Commas. This was a memorandum that was drawn up by a Committee that had been convened by the Secretary of State for India for the explicit purpose of taking into consideration the report by Drs. E. Klein and Heneage Gibbes that was entitled “An Inquiry into the Etiology of Asiatic Cholera.” From the report, we learn that Klein and Gibbes noted that it was sometimes difficult to find even one comma-shaped bacilli in the rice-water stools of cholera patients, and that there were acute cases in which the comma-bacilli were very scarce even after the disease had set in.

Drs. Klein and Gibbes write as follows:

“Comma-bacilli are present in the rice-water stools of cholera patients, but their number is subject to very great variations; while in some they are easily found, in others it is difficult to meet with one(p. 6)…”

"That there are acute cases in which the comma-bacilli are very scarce indeed, even after the disease has well set in; that they should have been present in sufficiently large numbers in the lower part of the ileum before the symptoms appeared,"

The researchers stated that, based upon their own observations along with those of others, that no direct relationship existed between the number of comma-shaped organisms associated with the choleraic process and the gravity of the disease. The bacilli were not found in the blood or tissues, and were not ordinarily, if ever, found in the tissues of any part of the intestinal canal in even the most acute cases of cholera.

"The foregoing extracts, especially when taken in connection with observations recorded by other observers, appear to justify the inference that no direct relation exists between the number of comma-shaped organisms associated with the choleraic process and the gravity of the disease, and that these organisms are not found in the blood or tissues, and are not ordinarily, if ever, to be found in the tissues of any part of the intestinal canal in even the most acute cases of cholera when the post-mortem examination is made immediately after death."

In direct opposition to Koch's first postulate, Klein and Gibbes found that the comma-bacilli were often present in other conditions. In fact, they identified the bacillus so often that they that were emphatic that the comma-bacilli occurs in cases of intestinal disease other than cholera.

"Passing on to the second of the above formulated propositions—that comma-bacilli are not found under any conditions other than cholera—Drs. Klein and Gibbes assert that “this cholera bacillus, or at any rate one that in morphological respects appears identical with it, occurs also in the stools of cases of diarrhoea. In an epidemic of diarrhoea that occurred in the autumn of 1883 in Cornwall, the stools of the patients contained … curved organisms which it is impossible to distinguish from the comma-bacillus of cholera stools; in size they are the same, in being curved they are the same, and, just as is the case with the choleraic comma-bacilli, some examples are either slightly pointed at the ends or blunt. They occurred not less numerously than they are sometimes found in cholera stools” (page 7). They were also met with in cases of dysentery and enteric catarrh, and “in a case of chronic phthisis of which a post-mortem examination was made, the mucus of the small intestine, although free of any tubercle bacilli, contained, besides other putrefactive organisms, also comma-bacilli, and in this case they were so distinct that there was no difficulty in identifying them, and they were as numerous as in many cholera stools that we have examined. In the stool of a case of diarrhoea of a child suffering from chronic peritonitis (February, 1882) there are present in specimens stained with Spiller’s purple numbers of comma-bacilli which it is impossible to distinguish from choleraic comma-bacilli; in size, shape, and general aspect they appear identical. On the whole, then, we maintain, contrary to Koch’s emphatic statement, that the comma-bacilli occur also in cases of intestinal disease other than cholera “(page 7).”

Upon investigating a water tank that Koch had visited, the researchers noted that, of about 200 families that regularly used the filthy water for bathing and drinking, only one cholera case had occurred. Even though the comma-bacillus was abundant in the water, no one else became a victim of the disease. It was an “experiment performed by nature on a large scale” that proved that the disease had nothing to do with the comma-bacillus.

“The same tank that plays such a conspicuous part in Koch’s report above mentioned was visited on the 26th November. It is surrounded by native huts in which about 200 families are living. There had occurred one case of cholera in this bustee about the first week of the month of November. The water of this tank was very dirty, particularly all along the shore, and the people around the tank, as is customary, made use of the water for all and every kind of domestic and other purposes, including drinking.

“A sample of this water was taken from near the shore, where it appeared particularly impure, about twenty yards from the house in which the cholera case had occurred, and the microscopic examination revealed undoubted commabacilli, identical in every respect with those found in choleraic dejecta. Notwithstanding their presence in this water, and notwithstanding the extensive use the 200 families were constantly making of it, there has been no outbreak of cholera. Now, we have in this instance an experiment performed by nature on a scale large enough to serve as an absolute and exact one. This water had been contaminated with choleraic evacuations, and of course with the comma-bacilli, and it was used extensively by many human beings for several weeks. If, to speak with Koch, the comma-bacilli were the cause and essence of cholera, how is it that not one person among so many has, until the middle of December, contracted the disease? Clearly because the water did not contain the cholera virus, and because this latter has nothing to do with the comma-bacilli” (p. 36)."

Klein and Gibbes noted that they performed the same animal experiments Koch claimed to have performed which included feeding, the use of subcutaneous, intraperitoneal, and intravenous injection, and injection into the cavity of the upper part of the small intestine of mucus flakes of the ileum of typical acute cholera, and of pure cultivations of choleraic comma-bacilli and the small straight bacilli. In all cases, it was not possible to produce the disease in any of the animals (mice, rats, cats, rabbits, and monkeys) tested. In fact, Klein and Gibbes stated that there was no direct experimental evidence that cholera can be induced in man by the introduction of a pure cultivation of comma-bacilli into his system. On the contrary, they pointed out that the comma-bacilli have been swallowed without any ill effect.

“When in Egypt and Calcutta, Koch performed a large number of experiments by feeding, subcutaneous and intravenous injection, as well as injection into the duodenum with rice-water stools and with pure cultivations of comma-bacilli, on rodents, carnivorous animals, and monkeys, and obtained no result, and his inquiries among the people led him to the conclusion that no case was known of a domestic animal having taken cholera, and he therefore came to the conclusion that cholera is not transmissible to the lower animals. He made, however, the observation that animals (rodents) may die of septicaemia after inoculation with rice-water stools, and that the comma-bacilli are capable of multiplication within the animals inoculated, without, however, producing cholera. Since his return to Berlin he maintained that he has been able to confirm the assertions of Nicati and Rietsch—viz. that injection of the comma-bacilli into the duodenum of dogs and guinea-pigs led to death with multiplication of the comma-bacilli, and he therefore considers it proved that the comma-bacilli are pathogenic organisms.

A large number of experiments were performed by one of us on rodents, cats, dogs, and monkeys by feeding, by subcutaneous, intraperitoneal, and intravenous injection, and by injection into the cavity of the upper part of the small intestine of mucus flakes of the ileum of typical acute cholera, and of pure cultivations of choleraic comma-bacilli and the small straight bacilli; the results of these experiments are described in the following pages” (pp. 19, 20).

“From all these experiments it follows that neither with mucus flakes taken from the ileum of acute cases of cholera nor with stools recent and old, nor with cultivations of comma-bacilli or small bacilli, is it possible to produce in animals (mice, rats, cats, rabbits, and monkeys) any illness, be the introduction into the system carried out by feeding, by subcutaneous injection into the jugular vein, or by injection into the cavity of the intestine “(p. 24).

As regards lower animals, therefore, it seems to us that it has been demonstrated that neither the alvine dejections of cholera nor cultivations of isolated comma-bacilli, obtained from such dejecta are capable of producing cholera, nor even of producing systems undoubtedly of a choleraic type. On the other hand, there is no direct experimental evidence, so far as we are aware, that cholera can be induced in man by the introduction of a pure cultivation of comma-bacilli into his system; on the contrary, it is alleged that they have been swallowed with impunity."

Based upon the findings of Klein and Gibbes report, the Comittee concluded that the “precise cause of cholera has not been ascertained.”

https://journals.biologists.com/jcs/article/s2-26/102/303/62010/The-Official-Refutation-of-Dr-Robert-Koch-s-Theory

Interestingly, even Louis Pasteur, considered the father of germ theory, disagreed with Koch on cholera. As advisor to the French commission, Pasteur wanted the members, including Isidore Strauss and Emile Roux, to refute Koch's theory. However, one of the most scathing refutations of Koch's cholera findings came from Henry Raymond Rogers, M.D. In his letter to the editor dated 1895, Rogers noted that the comma-shaped bacillus theory of cholera proved to be a failure. He noted that these “invisible comma-shaped germs” are found to be “universal and harmless.” These bacilli are found in the mouth and throat secretions of healthy people and are regularly seen in common diarrhea as well as swarming in the intestines of the healthy and in hardened fecal discharges. Rogers noted that Drs. Pettenkofer of Munich and Emmerich of Berlin, physicians that were considered of high distinction and experts in cholera, both drank a cubic centimeter of "culture broth" without experiencing even a single symptom characteristic of cholera. Rogers concluded that Koch's pernicious (i.e. having a harmful effect) cholera germ theory had the “most disastrous consequences in misleading mankind:”

Dr. Robert Koch and His Germ Theory of Cholera.

Dunkirk, N. Y., June, 1895.

To the Editor:—Dr. Robert Koch has sought to explain the cause of certain diseases upon the hypothesis of the action of pathogenic germs, invisible to the human eye. Upon the microscopic examination of the stools of cholera cases, he found different forms and kinds of germs, and among these was one of comma-shape, which he fancied was the cause of this disease. Through the process of "culture," and "experiment" upon the lower animals he asserts he has demonstrated that this germ is the actual cause of this disease. So confident was he that this newly discovered, comma-shaped object was the cause of cholera that for several years he continued to assert with the utmost assurance that the presence of these comma-shaped bacilli in the dejections of a person suspected of having this disease, constitutes positive evidence that the case is one of pure Asiatic cholera.

But this comma-shaped bacillus theory of cholera has proved a failure. These invisible comma-shaped germs are now found to be universal and harmless. They are found in the secretions of the mouth and throat of healthy persons, and in the common diarrheas of summer everywhere—they swarm in the intestines of the healthy and are observed in hardened fecal discharges as well. Dr. Koch to-day asserts that these bacilli are universally present. He even tells us that: "Water from whatever source frequently, not to say invariably, contains comma-shaped organisms."

Drs. Pettenkofer of Munich and Emmerich of Berlin, physicians of high distinction and experts in this disease, drank each a cubic centimeter of "culture broth" which contained these bacilli, without experiencing a single symptom characteristic of cholera, although the draught in each instance was followed by liquid stools swarming with these germs.

Dr. Koch has kept au courant with the foregoing facts, as well as others quite as significant, and, had he accepted the evidences which thus year after year have been forced upon him, his pernicious cholera germ theory with its most disastrous consequences in misleading mankind would have been unknown to-day.

Henry Raymond Rogers, M.D.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/453342

According to Rogers, Robert Koch knew that the accumulating evidence for his comma-shaped bacillus contradicted his own postulates and disproved the notion that the bacterium was the cause of disease. He knew that this bacillus was regularly found in those who are healthy. Koch also knew that it was not found in every case of the disease. He even knew that it did not make humans sick as he failed to recreate cholera in himself after drinking pure culture. We can see evidence of this knowledge from a few sources. In a 2011 paper, it is said that Koch failed to infect animals as well as himself with pure cultures, lending Koch to ridicule by his opponents:

Lessons from cholera & Vibrio cholerae

“In order to fulfill the criteria laid down in the remaining two of his postulates, Koch tried to infect animals with pure cultures of the organism with little success. He rightly concluded that the animals were not susceptible to cholera and took recourse to the extreme step of infecting himself by drinking pure cultures. However, he came down with only a mild episode of diarrhoea, an outcome which was later on exploited by his opponents to ridicule him.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3089047/

The 1884 paper Cholera And Its Bacillus stated that Koch had failed to find the comma-bacilli in cases of cholera nostras, which is clinically indistinguishable from cases that were said to be caused by vibrio cholerae.

“Dr. Koch had recently examined sections of the intestinal mucous membrane of a rapidly fatal case of cholera nostras. There were no comma-bacilli, but a great number of other bacilli were seen on the surface of the intestine and in the utricular glands. In some specimens from Vienna, prepared from cases which might have been instances of cholera nostras, but which also might have been death from sunstroke, Dr. Koch had failed to find comma-bacill.”

https://www.jstor.org/stable/25270209?seq=1

From Robert Koch's own writings, we can see that he knew that the comma-shaped bacillus was not found in all cases of those said to be afflicted with cholera. Koch tried to rationalize the absence of his “causative agent” by claiming that it was due either to inexperienced investigators or from the timing of when the samples were taken:

On the current status of bacteriological cholera diagnosis

“This is not to say, however, that conversely the absence or rather the non-detection of cholera bacteria in a case suspected of having cholera proves the absence of cholera under all circumstances. Just as with other infectious diseases caused by microorganisms, there can also be isolated cases of cholera which, because of their behavior in other respects, must be regarded as indubitable cases of cholera, but in which cases, either because the investigator is insufficiently qualified or because they were examined at an unsuitable point in time are, the cholera bacteria are not found.”

Koch also knew that his bacillus was found in healthy people. Despite this fact, he still considered these people as cholera cases even though they suffered no disease:

“These mildest cases of cholera, in which cholera bacteria have been found in the solid deposits of apparently healthy people, occur only among groups of people who have been equally exposed to the infection and who show severe cases as well as the mild ones. Nothing of the kind has ever been found in persons who could not possibly have been infected. One must therefore regard these cases as real cases of cholera and cannot use them as evidence against the specific character of the cholera bacteria.”

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02284324

Robert Koch failed his first logical postulate when he found healthy carriers of the comma-shaped bacillus as well as when he was unable to find the bacterium in all cases of the disease. Koch failed his third postulate, and subsequently his fourth as well, when he was unable to recreate the disease not only in animals, but also in himself. Thus, we can see that Robert Koch only fulfilled his second postulate for his claim that the vibrio cholerae was the causative agent of disease. Koch abandoned his own sound logic and reasoning in order to be recognized as the discoverer of the causative agent of cholera. This has led future researchers to claim that, because Koch abandoned his first (and in the case of cholera, third and fourth) postulates, they may do the same following his example. This is why Koch's Postulates are both highly praised as essential and ridiculed as severely limited at the same time. The “great microbe hunter” sold out for fame and prestige, and he was awarded with the Order of the Crown (one of the highest honors), 100,000 marks (over $57,000 in USD), and appointments such as Privy Imperial Councilor by Emperor Wilhelm I, Professor of Hygiene at the University of Berlin, and Director of the Hygiene Institute in 1891. The Hygiene Institute was renamed the Robert Koch Institute upon his death in 1910. As the French wrote, Koch had followed a false trail. However, he was unwilling to give up his decorations. Because of Koch's actions, he and his ilk have been misleading mankind with disastrous consequences ever since.

had a very interesting article discussing the construction of the “viral” genome and why the ends are important. shared the good news that a “no-virus” FOI was put on the public record. presented a roundtable conversation focusing on lack of proof of transmission of a “viral” agent and the fallacy that is the current isolation process. launched the upcoming first season of an exciting new podcast coming soon. started an investigation into the new CDC director. had a very entertaining look at what the Japanese think is visual evidence of a “virus,” with a wonderful 80s-inspired tribute to the excellent work ofHere is the play-by-play from

Thank you for exposing the Virology and Germ Theory fraud!

Here's an introductory playlist to help people discover the truth about "viruses" and "Germ Theory"

https://odysee.com/@PabloElSabio:2/TerrainTheory:9

🔴48 videos with links to supporting studies!

The truth is out and the Pharma frauds are exposed.

Are there enough out there paying attention?

There is no virus, there is no pandemic! All a planned attack

to steal our health, wealth and freedom.

One of my favorite articles.

🎯 https://drsambailey.com/why-nobody-had-caught-or-got-covid-19/

So much for a “virus”-free vacation.