How HIV Fails Koch's Postulates

Virologists can't get no (da da da)...satisfaction...(da da da)...even though they try and they try and they try and they try...

I often find inspiration for my writing through interactions on Twitter—or X, as it’s now known—particularly when these exchanges spark ideas or lead me to explore new topics. Sometimes, someone poses a challenge that requires me to dig deeper and investigate, leading to the discovery of valuable information that I feel compelled to analyze and share. These moments are the most rewarding, and I genuinely appreciate them, though they are unfortunately rare.

More often, I find myself engaging with individuals who not only lack a solid understanding of the topic at hand but also present arguments that can be easily refuted—even using their own sources. While I don't mind addressing these claims, it becomes tedious to repeatedly gather the same pieces of information. To save myself time and effort, I end up compiling my findings into articles. This way, when the same arguments inevitably resurface, I’ll have a comprehensive resource ready to go.

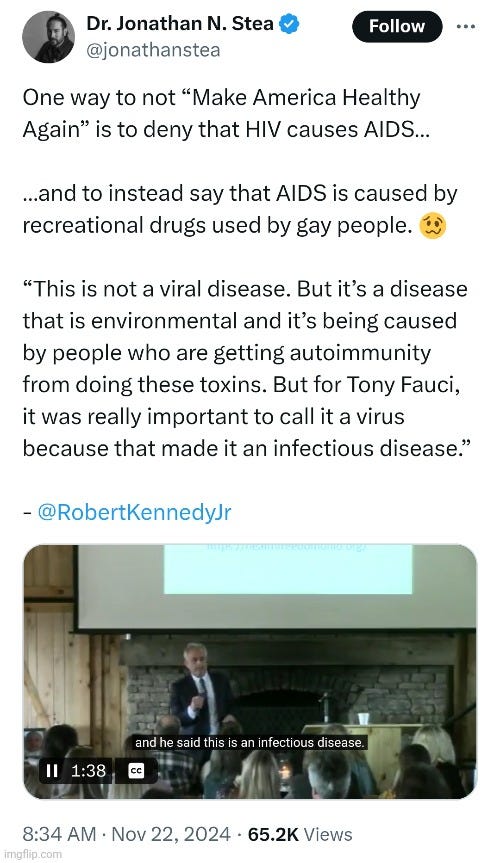

A recent example of this dynamic arose from a challenge I posed in response to a tweet by clinical psychologist Jonathan Stea on November 22, 2024. In his post, Jonathan claimed that denying HIV as the cause of AIDS is “one way to not make America healthy again,” using a quote from “anti-vax” proponent Robert Kennedy Jr. to support his point.

Noticing the implicit positive claim that HIV, rather than recreational drug use, is the cause of AIDS, I naturally requested the necessary scientific evidence that Jonathan must have relied upon to establish this chain of causation.

Unfortunately, having interacted with Mr. Stea before, I was not surprised by his response—or lack thereof. Despite his self-professed “expertise” in science and his vocal opposition to pseudoscience, his actions often contradict these principles. When challenged to substantiate the claims he makes in his posts, Mr. Stea consistently falls short. He neither provides credible evidence for his assertions nor engages in logical counterarguments. Instead, he resorts to highlighting comments for his followers to mock, punctuated by the occasional laughing emoji.

In this particular instance, rather than addressing my request for evidence, Jonathan deflected. He highlighted my comment and offered an irrelevant commentary about “germ theory denialism,” which failed to engage with the specific points I raised. By sidestepping his inability to substantiate his positive claim, he once again relied on his followers to “debate” on his behalf, avoiding direct accountability for his assertions.

While I anticipated numerous fallacious comments from his followers, I was surprised that no one directly challenged my point about the lack of scientific evidence, derived from the scientific method, supporting the claim that HIV causes AIDS. Instead, most responses—when not resorting to ad hominem attacks—focused on my inclusion of Koch's Postulates as a necessary criterion.

Developed by German bacteriologist Robert Koch in the late 19th century, these postulates outline four logical criteria necessary to establish that a microbe causes a specific disease. They emphasize association, isolation, causation, and re-isolation. While phrased slightly differently in various sources, the postulates are most commonly stated as follows:

The microorganism must be found in abundance in all cases of those suffering from the disease, but should not be found in healthy subjects.

The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased subject and grown in pure culture.

The cultured microorganism should cause the exact same disease when introduced into a healthy subject.

The microorganism must be reisolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

Many of Mr. Stea's followers dismissed Koch's Postulates as outdated or not applicable to “viruses,” ignoring the fact that even though these logical principles were popularized by Robert Koch in the late 1800s, they remain timeless. The four postulates are rooted in pure logic, providing a framework for falsifiability and aligning seamlessly with the scientific method. When attempting to prove that any microbe causes a specific disease, Koch's Postulates are not just relevant—they are an essential extension of the scientific method. The two cannot be separated.

To address this argument, I recently reviewed information from organizations that actively support germ “theory” and virology, including the NIH, CDC, WHO, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, and the American Association of Immunologists, among others. These sources confirm that evidence derived from the scientific method and satisfying Koch's Postulates is essential to definitively prove that any microbe causes disease. Thus, this objection to the inclusion of Koch's Postulates based on their age or relevance to “viruses” is entirely invalid.

Interestingly, while most of Mr. Stea's followers attempted—and failed—to dismiss Koch's Postulates as outdated or irrelevant to “viruses,” others contradicted these claims by asserting that the postulates had indeed been satisfied for HIV.

Some would supply editorials or articles claiming the postulates had been met, while others used AI-generated responses, such as those from Google searches or Grok—a generative AI chatbot accessing real-time information from X—to support their arguments.

However, despite their best efforts, they were ultimately unsuccessful in demonstrating that Koch's Postulates have been satisfied for HIV, as the available evidence fails outright from the very first step. In the interest of putting this debate to bed for good, let’s examine their claims and explore why their arguments are mistaken. It's time to show how HIV fails Koch's Postulates.

“Let me suggest that those who are currently searching for the AIDS agent read Koch's paper. Might I even suggest that editors of journals do the same? If authors and editors of AIDS papers adhered to the rigors of Koch's analysis of the facts, we would not be annoyed by premature claims concerning the etiology of AIDS. Koch's postulates are the principles that establish a relationship between a microbe and a disease... [and] if we abide by the scientific guidance of Koch's postulates, we are sure to discover the cause of AIDS.”

-Dr. Richard Krause

In the early 1980s, researchers for the CDC approached the emerging “AIDS crisis” with the assumption that a transmissible agent—presumed to be a “virus”—was the only plausible explanation for AIDS across different risk groups. However, their inability to identify any known “virus” or microorganism as the causative agent eventually shifted their focus to “retroviruses,” a relatively new classification of “viruses” first described in 1971. These “viruses,” which are said to use RNA as their genetic material, rely on the enzyme reverse transcriptase to convert RNA into DNA within host cells. Initially, “retroviruses” had been associated with certain cancers.

The first “retrovirus” proposed as a leading candidate for the cause of AIDS was HTLV-1, or “human T-cell leukemia virus.” Discovered in 1981, it was associated with a rare type of leukemia found primarily in southern Japan and the Caribbean. However, HTLV-1 quickly fell out of favor as the main suspect when researchers failed to detect it consistently in AIDS cases, and its associated leukemia was rare outside of these regions.

In 1983, the “retrovirus” theory gained new momentum when a French research team led by Luc Montagnier identified what they called the “lymphadenopathy-associated virus” (LAV) in swollen lymph nodes from a homosexual man with a history of over 50 sexual partners. At the time, it was uncertain whether LAV was truly a “retrovirus” or part of a different “viral” family altogether. Montagnier later admitted that a French specialist in electron microscopy of “retroviruses” publicly criticized him, stating, “This is not a retrovirus, it is an arenavirus.” Interestingly, Montagnier's team reported having “isolated” about a dozen “viruses” that were either identical to or similar to LAV based on electron microscopy and immunologic studies.

On April 23, 1984, Dr. Robert Gallo of the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Dr. Margaret Heckler, then U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, announced the discovery of the “probable” cause of AIDS: a “virus” they called HTLV-3. Heckler described it as a “variant” of a known human cancer “virus” and claimed its identification allowed for mass production of the “virus,” enabling the creation of blood (“antibody”) tests purported to identify AIDS victims with “essentially 100% certainty.”

At the time of the announcement, the head of the CDC believed that Montagnier's LAV was the cause of AIDS. Heckler dismissed the discrepancy, asserting that HTLV-3 and LAV “will prove to be the same.” Gallo supported this position, stating, “If the two culprits turn out to be the same, I will say so.” Dr. James Curran, head of the CDC's AIDS investigation team, expressed hope that the two “viruses” were indeed identical, warning that if they were not, “then something is wrong because one virus causes AIDS.”

However, several challenges to the claim that either “virus” was the cause of AIDS undermined the assertion. Tests developed for LAV or HTLV-3 yielded negative results in some patients presumed to have AIDS. Additionally, researchers at the CDC in Atlanta, the Pasteur Institute, and other institutions failed to induce AIDS in animals by injecting them with the “viruses.” Therefore, the claim by Heckler and Gallo that they had discovered the “probable” cause of AIDS was based entirely on indirect serological and epidemiological observations, rather than the direct fulfillment of the logical causation criteria set forth by Koch's Postulates. Were Heckler and Gallo's bold claims sufficient evidence to assert that HIV was the “probable cause” of AIDS? Did the evidence satisfy Koch's logical criteria for proving causation?

As highlighted by Dr. Richard Krause in 1983, it was crucial for those investigating the cause of AIDS to apply and fulfill Koch's Postulates in order to substantiate claims of causation. Dr. Krause expressed confidence that adhering to these scientific principles would eventually lead to the discovery of the responsible agent, whether it was something entirely new or a long-dormant entity. In his 1988 paper HIV Is Not the Cause of AIDS, renowned retrovirologist Peter Duesberg echoed this sentiment, emphasizing the importance of fulfilling Koch's Postulates. Duesberg boldly declared that HIV “fails to meet the postulates of Koch and Henle, as well as six cardinal rules of virology.”

The 1994 article Fulfilling Koch's Postulates noted that Koch's criteria for proving that a disease is caused by a specific microbe had become a standard in medicine. It also acknowledged that many AIDS researchers agreed with Duesberg’s assessment that HIV had not satisfied Koch's Postulates. However, these researchers disagreed with his conclusion, arguing that the failure to meet Koch’s Postulates did not necessarily rule out HIV as the cause of AIDS, as many other diseases had been attributed to a cause despite not fulfilling the postulates. In fact, some leading AIDS researchers had even stopped acknowledging that HIV did not meet Koch’s Postulates, claiming instead that they had been satisfied. Let’s examine why these “leading AIDS researchers” were wrong.

Postulate 1: The microorganism must be found in abundance in all cases of those suffering from the disease, but should not be found in healthy subjects.

Koch's first logical rule establishes a framework for falsifiability—the ability to disprove a hypothesis. According to the germ hypothesis, specific microbes are pathogens capable of causing specific diseases. Therefore, these presumed pathogens should be found in abundance in the fluids of hosts suffering from the disease. This hypothesis can be falsified by finding the presumed pathogens in healthy individuals where they do not cause disease, by identifying the pathogen in diseases with which it is not associated, or by observing cases of the disease where the pathogen is absent. This postulate serves as a critical safeguard against mistaking correlation for causation, ensuring that the hypothesis is testable and open to challenge—a cornerstone of scientific rigor.

It is asserted by those who claim Koch's Postulates have been satisfied for HIV that the “virus” is found in all AIDS cases. In her proclamation of HIV being the “probable” cause of AIDS, Heckler claimed that “antibody” tests could identify AIDS victims with “essentially 100% certainty.” This was echoed in O'Brien and Goedert's 1996 editorial HIV causes AIDS: Koch's postulates fulfilled, which asserts that HIV fulfills Koch's first postulate based on “epidemiological concordance of HIV exposure and AIDS,” with studies documenting the presence of HIV or HIV “antibodies” in over 95% of AIDS patients worldwide. According to the article HIV Causes AIDS: Proof Derived from Koch's Postulates on TheBody.com, PCR findings of HIV in AIDS cases further support this claim, though earlier difficulties detecting HIV were acknowledged.

Setting aside the fraudulent nature of HIV tests for the moment, as well as the paradoxical notion of “antibodies” serving as a marker of active “infection” rather than “immunity,” as noted by O'Brien and Goedert, a particular concern of those challenging the HIV=AIDS is the occurrence of AIDS-defining conditions in patients who are HIV “antibody” negative. In other words, the claim that HIV is present in all cases of those with AIDS is incorrect, which is in direct contradiction to Koch's first postulate stating that the microbe should be present in abundance in all cases of the disease. The cases where HIV is said to be absent are referred to as idiopathic CD4+ T-lymphocytopenia (ICL), otherwise known as Non-HIV AIDS. This was described in the 1996 paper Non-HIV AIDS: nature and strategies for its management where it is noted that those with severe opportunistic “infections” without evidence of HIV did not present a new disease or one caused by an “infectious agent.” Interestingly, it was also noted that a group of asymptomatic subjects with low CD4 counts were found in the screening of healthy individuals without any illness.

“Despite initial claims to the contrary, a cluster of reports of severe opportunistic infections occurring in patients without evidence of HIV infection do not appear to represent a new disease entity or present evidence of epidemiologically associated cases suggesting an infectious agent. Reported cases are reviewed and appear to represent a heterogeneous group, many of which may represent sporadic cases of late onset acquired immunodeficiency. In addition, a small group of asymptomatic subjects have been identified with constitutively low CD4 T cell populations which appear to have little or no clinical significance since these patients have no evidence of clinical immunodeficiency.”

These are rather damning statements as the CDC defines AIDS cases when a person's CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells per milliliter of blood, or they develop certain illnesses called “opportunistic infections.” The paper goes on to explain that these cases rekindled the debate over whether HIV truly was the cause of AIDS. In fact, at the Eighth International AIDS Conference, the possibility was floated that many AIDS cases may not be caused by HIV. However, the CDC responded by redefining such cases under the label ICL, avoiding a direct challenge to the HIV=AIDS paradigm.

“The unexpected announcement of the Eighth International AIDS Conference, Amsterdam, that the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta were investigating a series of reported cases of AIDS in which HIV did not seem to be implicated rekindled many of these issues.

At this conference the possibility was discussed that many AIDS cases might not be caused by HIV, raising fears that another transmissible agent for AIDS might exist and that this could render national blood supplies unsafe due to another virus for which there was no satisfactory screening test. Later, the CDC in Atlanta convened a meeting on the subject and issued a provisional case definition for the condition 'idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia' which identified a group of patients with the presentation described above.”

“The syndrome of idiopathic CD4 + T lymphocytopenia is defined by the Centers for Disease Control (1992) as cases which demonstrate depressed numbers (<3OO/mm3) and proportions (<20% of total T cells) on at least two consecutive occasions, with no laboratory evidence of HIV-1 or HIV-2 infection, and the absence of any defined primary or secondary immunodeficiency disease or therapy associated with depressed levels of CD4+ T lymphocytes.”

Low CD4 counts, often used as a marker for AIDS, have been detected in entirely healthy individuals during investigations and screenings—even among “high-risk” groups such as blood donors and homosexual men—further complicating the HIV=AIDS narrative. These individuals consistently exhibited constitutionally low CD4 levels over time without any signs of illness. With no evidence of functional cellular deficiency, immunocompromise, or clinical disease, their low CD4 counts were ultimately deemed to have no prognostic significance.

“Although a number of patients fulfilling the above criteria have come to light as the result of investigation of possible cellular deficiency suspected on clinical grounds, other cases have been detected as a result of the investigation or screening of healthy populations including blood donors, homosexual men and other groups.”

“The first is a small number of individuals whose CD4 counts are below the lower end of the normal range and who have constitutionally low CD4 blood levels consistently over a period of time without ill effect. It is not surprising that such individuals have been identified given the large numbers of blood donors and cohort populations under study. These individuals may show consistently low counts but on further investigation they usually have no evidence of functional cellular deficiency. Since these individuals are probably not functionally immunocompromised and show no clinical signs, their low CD4 counts may have no prognostic significance. Most of these individuals will require no active management or prophylaxis.”

There are numerous documented instances where individuals met the clinical criteria for an AIDS diagnosis while remaining either HIV-negative or entirely healthy. Professor Duesberg noted that it is not possible to detect free “virus,” “provirus,” or “viral” RNA in all cases of AIDS. In fact, the “virus” cannot be “isolated’ from 20 to 50% of AIDS cases. Similarly, The Perth Group, another prominent challenger of the HIV/AIDS hypothesis, noted in their analysis of Robert Gallo's foundational study that HIV was “isolated” in fewer than half of AIDS patients with opportunistic “infections” (10 out of 21 cases) and in less than one-third of those with Kaposi's sarcoma (13 out of 43 cases)—two hallmark conditions of AIDS.

Moreover, even among individuals diagnosed as HIV-positive, clinical latency can last for decades, with periods ranging from several months to over 30 years, during which no symptoms of AIDS manifest. According to Planned Parenthood, individuals with HIV often show no symptoms initially, appearing and feeling completely healthy long after their presumed “infection.” In fact, they may never even know they are “infected” as these individuals are free of AIDS-defining diseases for decades, if they ever come down with them at all. In many cases, these individuals are labeled as long-term non-progressors (LTNPs)—individuals who are “infected” with HIV but do not develop symptoms even without treatment. This is often used to explain away contradictory evidence against the HIV/AIDS hypothesis. LTNPs are typically said to have high CD4+ counts and low plasma “viral” loads. However, one study showed that 70% of LTNPs had “viral” loads greater than 10,000 copies/ml, with two individuals showing “viral” loads over 30,000 copies/ml, challenging the expectation that LTNPs, by definition, have very low or undetectable “viral” loads. Meanwhile, it has been stated that these individuals can have CD4+T cells counts below < 200 / ml without illness, which undermines the belief that normal CD4+ T-cell counts are necessary to prevent opportunistic “infections” and AIDS. Interestingly, one study of LTPNs found that HIV could not be “isolated” in 35% of cases, further complicating the standard narrative.

This variability in the presence and absence of the “virus” alongside the presence or absence of disease further undermines the causal link between HIV and AIDS. The “presence” of HIV in individuals without disease, alongside its “absence” in many diagnosed with AIDS, fails to satisfy Koch's Postulates. Specifically, it violates the first criterion: the consistent association of the pathogen with the disease.

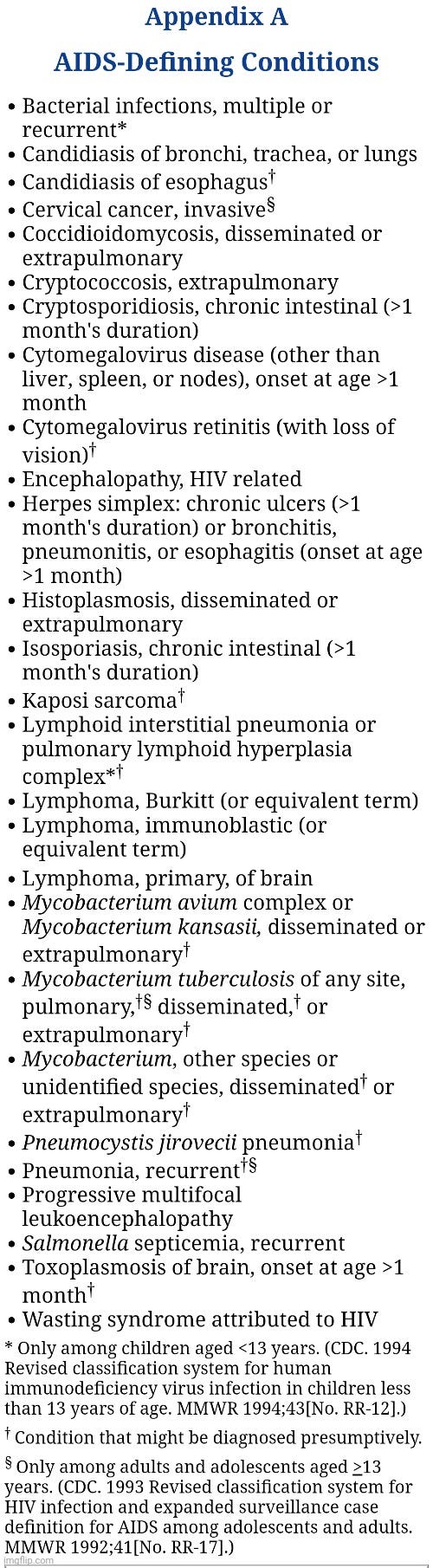

HIV further violates Koch's first postulate because it is implicated in a collection of pre-existing diseases rather than a singular, distinct condition. The CDC lists 27 different diseases under the AIDS umbrella, including bacterial “infections,” cervical cancer, herpes simplex, lymphoma, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. Each of these diseases can occur independently of an HIV-positive test, demonstrating that the presence of the so-called “virus” is not necessary for their occurrence.

The fact that these illnesses arise without HIV undermines the claim that HIV alone fulfills Koch's first postulate as the sole and necessary cause of AIDS. This conflation of correlation with causation in the HIV/AIDS hypothesis highlights the need for adherence to rigorous scientific standards, such as Koch's Postulates, to establish causality. From the very start, the foundational evidence for HIV as the causative agent of AIDS fails to meet the logical criterion established to prove any microbe as the causative agent of disease.

2. The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased subject and grown in pure culture.

Brent Leung: What is the purpose of the purification?

Luc Montagnier: To make sure you have a real virus.

https://x.com/ViroLIEgy/status/1621162640621056000

I repeat we did not purify.

-Luc Montagnier

In 1881, Robert Koch underscored the significance of pure cultures in “infectious” disease research, stating, “The pure culture is the foundation for all research on infectious diseases.” This marked a pivotal advancement in microbiology, as Koch developed techniques for isolating and cultivating single species of microorganisms. These methods allowed researchers to have the ability to attempt to demonstrate causal links between specific microbes and diseases, a principle that became central to Koch's Postulates in subsequent years. While achieving pure cultures was a significant challenge at the time, Koch's innovations in solid media transformed bacteriology, setting rigorous standards for disease research.

The inclusion of the pure culture requirement aligns with the principles of the scientific method: to establish causation, the microbe must be isolated from all potential confounding variables so that it can function as the independent variable (the presumed cause) in experiments. Obtaining a pure culture of bacteria is a straightforward process that begins with collecting a sample, such as blood, tissue, or other fluids, using sterile techniques to avoid contamination. A stained smear (e.g., Gram stain) can be examined under a microscope to confirm the existence of bacteria in the sample and to identify their morphology, providing a preliminary classification before proceeding with culturing.

The sample is streaked onto an agar plate, often using selective media to encourage the growth of the target bacterium while inhibiting others. The streaking method spreads the bacteria to isolate individual colonies, which are incubated under appropriate conditions for growth. After incubation, a single, well-separated colony is selected and transferred to a new agar plate or broth for further growth. This process may be repeated to ensure purity. Once isolated, the bacterium is examined microscopically and subjected to biochemical or genetic tests for characterization. This rigorous step-by-step process ensures that only one type of bacterium is present in the culture, making it ready for study or experimentation.

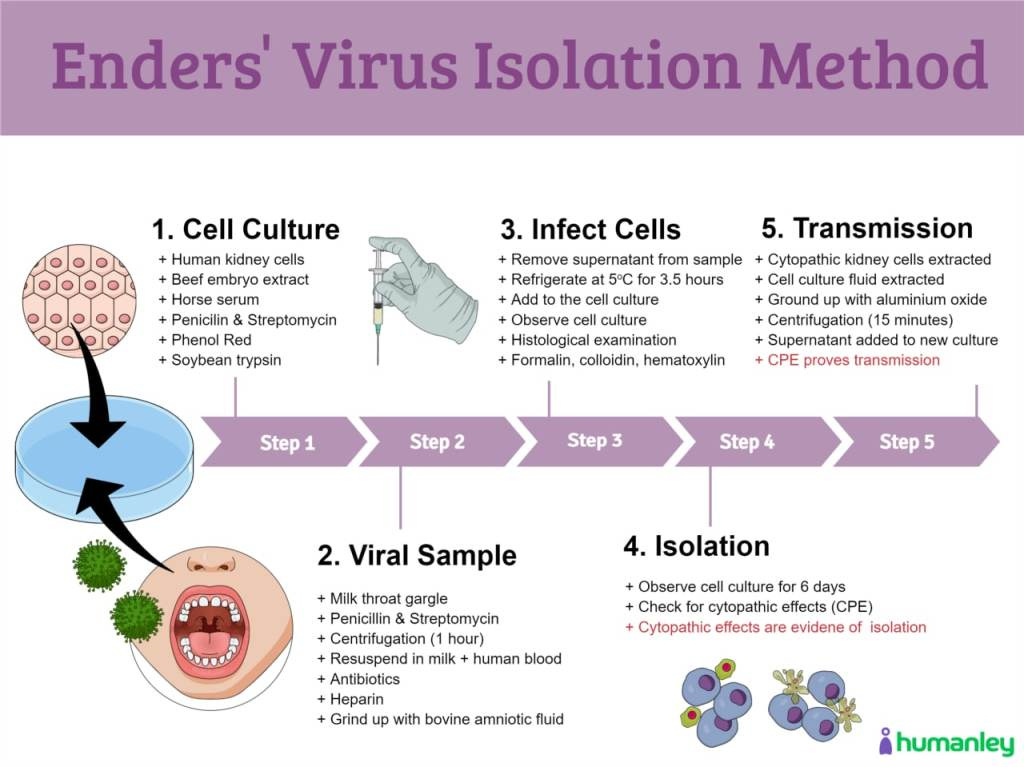

In virology, the process of identifying and isolating a “virus” is markedly different from bacteriology and lacks direct observation or purification. Virologists typically start with an unpurified sample from a host, presumed to contain the “virus” without ever directly identifying it, and mix it with a transport medium containing substances like fetal bovine serum, antimicrobials, and nutrients. This mixture is then introduced to a cell culture, usually derived from animal, embryonic, or cancerous cells, which also contains similar additive substances. The cell culture is incubated, and researchers observe for cytopathogenic effects (CPE)—a form of cell death that can result from many factors unrelated to the presence of a “virus.” Despite this, the CPE is often taken as evidence of “viral” activity. However, the process does not yield a purified or isolated “virus.” Instead, the result is a mixture of host materials, animal materials, nutrients, and other unknown elements, complicating claims of causation and the identification of the “virus” itself.

This inability to purify “viruses” raises a fundamental issue with Koch’s second postulate: the suspected pathogen must be isolated—separated from everything else—in pure culture. Virologists rely on indirect methods, such as cell cultures, to “grow” the “virus” that is never directly identified in the sample from the beginning. The CDC acknowledged, in a Freedom of Information Request obtained by Christine Massey, that “viruses need cells to replicate,” which results in samples mixed with other genetic material. They state that purification from the fluids is outside of what is possible in virology. Siouxsie Wiles of the University of Auckland similarly notes that “viruses” cannot be separated from host components, rendering the process of purification impossible.

This lack of direct evidence for “virus” existence at the start of experimentation undermines the foundational requirement for establishing causation: the presumed cause must exist independently before the observed effect, ensuring a proper time-order association. This requirement guarantees that variation in the independent variable precedes and drives variation in the dependent variable. Without a purified, isolated “virus” as the independent variable, experiments become inherently confounded by other variables present in the unpurified culture. Furthermore, using the observed effect—cytopathic effects (CPE)—as evidence for the existence of the presumed cause, the “virus,” is a logical fallacy. CPE, an effect, cannot be used to retroactively claim the existence of its cause without independent verification, as this would constitute affirming the consequent. This raises serious concerns about the logical foundations of virology and its adherence to the scientific method, particularly the necessity of a clearly defined and manipulable independent variable.

Despite the inability to obtain pure samples of a single “viral” species, researchers still claim that HIV satisfies Koch's second postulate. This is achieved by redefining “isolation” as a sample taken from an “infected” host and propagated in culture, bypassing the purification requirement. O'Brien and Goedert cite multiple “isolates” cultured from AIDS patients in human T lymphocytes, macrophages, and immortalized cell lines, relying on in vitro culture, PCR amplification, and “antibody” titers, even while admitting that “virus isolation” often fails. TheBody.com echoes this, highlighting advances in lab techniques that supposedly allow the growth of HIV from blood samples of people with AIDS and almost all of those with positive “antibody” tests.

However, as Peter Duesberg noted, this evidence for “isolation” is highly indirect and fails in 20-50% of AIDS cases. Cultures involving T lymphocytes, macrophages, and immortalized cell lines contradict the notion of purification, as these preparations contain a mixture of substances. Despite the fact that pure samples of “viruses” remain elusive, The Perth Group stressed that all retrovirologists, including Luc Montagnier, agree that purifying and isolating “viral” particles from everything else is essential to characterizing “viral” proteins and RNA:

“All retrovirologists, including Montagnier, agree that the only way to characterise the viral proteins (and RNA) is to purify the viral particles. That is, one must obtain the viral particles separated, isolated everything else that is not viral particles. Or at the very least, from everything else that contains proteins (and RNA).”

Luc Montagnier himself, in a 1997 interview with Djamel Tahi, reiterated the necessity of purification for protein analysis: “Analysis of the proteins of the virus demands mass production and purification. It is necessary to do that. And there I should say that that partially failed.”

Robert Gallo, in his 1976 paper Reverse transcriptase of RNA tumor viruses and animal cells, emphasized that “it is essential to use virus preparations as free of cellular contaminants as possible” for detecting and analyzing “virus-associated enzyme reactions.”

In an interview with Brent Leung for the documentary House of Numbers, Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, a key figure in Montagnier's team, spoke about the importance of using purified “virus” preparations for “antibody” detection kits to ensure specificity. Without a purified sample, the test will detect all of the proteins in the cell culture supernatant, which contains a mixture of everything:

“It was important to prepare kits for antibody detection. OK? Because we wanted these diagnosis kits to be as specific as possible. If you use a preparation of virus which is not purified of course you will detect antibody to everything, not only against the virus but also against all the proteins that are produced in the supernatant…Now when this virus [HIV] is in this [cell culture] supernatant it’s not purified. OK? Because the cells are releasing plenty of things, not only the virus...cellular proteins...so on, OK?...so that means in the supernatant you have a mixture of everything, including the virus. Then you have to purify it...OK...this is the second step...then you try to purify the virus from all this mess.”

Thus, it is evident that, in line with Koch’s second postulate, the virologists involved with HIV understood the importance of purification to, as Montagnier stated, “make sure you have a real virus.” Without purification, the indirect measures commonly cited by individuals like O'Brien and Goedert—such as in vitro culture, PCR amplification, and “antibody” titers—are scientifically meaningless in proving HIV's existence or its causal role in AIDS.

Alarmingly, HIV was never purified, isolated, or characterized directly from the fluids of an AIDS case prior to any cell culture experiments. Luc Montagnier himself admitted this, explaining that purification was avoided to prevent damaging the “infectious” particles:

“I repeat we did not purify. We purified to characterise the density of the RT, which was soundly that of a retrovirus. But we didn’t take the ‘peak’…or it didn’t work…because if you purify, you damage. So for infectious particles it is better to not touch them too much.”

He further acknowledged the lack of sufficient particles for purification:

“One had not enough particles produced to purify and characterise the viral proteins. It couldn’t be done. One couldn’t produce a lot of virus at that time because this virus didn’t emerge in the immortal cell line.”

Montagnier also stated that he believed that Gallo's team did not purify as well:

“Gallo?…I don’t know if he really purified. I don’t believe so. I believe he launched very quickly into the molecular part, that’s to say cloning.”

Dr. Dominic Edmund Dwyer, who worked with Montagnier at the Pasteur Institute, confirmed Montagnier's assertion that HIV was not purified. He detailed this during his testimony in the 2007 Paranzee trial, where a South African man was charged with intentionally “infecting” his partners by failing to disclose his HIV-positive status.

“It was collected from an infected person, it was put into other cells and then put into other cells yet again, and that’s exactly what isolation is all about. When it comes to purifying virus, if you start undertaking the other analyses to determine the protein structure, the electron microscopy structure, they didn’t do that in their paper.”

This was further confirmed by Robert Gallo's testimony at the same trial, where he acknowledged the necessity of purification but paradoxically argued against the ability to achieve true purification using sucrose gradient centrifugation. Despite this, he simultaneously claimed that the proteins of the “virus” had been purified.

“You have to purify. The witness shows a complete lack of understanding because a sucrose gradient barely purifies. She is always talking about purifying it into a gradient and then you have to do that to co-purify.”

“And you know, I mean, all this purification, it is an extreme wild goose chase. The genes of the virus are cloned now. All the proteins are purified.”

In further testimony, Gallo admitted that “viral” samples contained cellular proteins and acknowledged that centrifuging the sample through a sucrose gradient, even up to five times, does not purify a “virus.” He also noted that Montagnier was unable to purify any “virus” and did not claim his “discovery” was the cause of disease.

Gallo attempted to redefine “purification,” not as isolating the “virus” to a pure state, but as growing it in large quantities relative to cellular material. He argued that this “mass production” sufficiently separated the “virus” from cellular debris.

“All such viruses carry within them, right within the virus, if you purify you see it is all over, cellular proteins that are not virus encoded. In addition, around the virus you’ll still have some cellular protein. You can’t purify just by putting it through sucrose gradient. Montagnier’s early problem was inadequate growth of the virus. I’m saying this repeatedly and I don’t want to say it as a criticism of Montagnier’s paper. He reported a new retrovirus particle. He could transmit it invitro. He didn’t say it was the cause of virus in the baby. He couldn’t characterise it well. We cannot fault him for that because he couldn’t grow it properly. Once we could mass-produce this virus, that’s purification. If you have a tonne of something and you contaminate it by a drop of water, didn’t you purify it? It’s the ratio of cell protein to viral protein.

Sucrose gradient gives you a little bit of help but you could do that five times and it’s not going to purify as much as we did by mass-producing it. To use the extreme hyperbole, if you have a tonne of some something and a drop of water, you’ve purified it. That what we did.”

However, this interpretation conflicts with traditional scientific standards, where purification entails isolating a substance—such as a “virus”—from all other components to ensure a contaminant-free sample. Gallo's method fails to meet the standard of purity required by Koch's second postulate. Without purifying and isolating the “virus,” it is impossible to determine which proteins are “viral” and which are cellular. By acknowledging the presence of cellular proteins and other “non-viral” material within the sample, Gallo effectively conceded that his method does not constitute true purification.

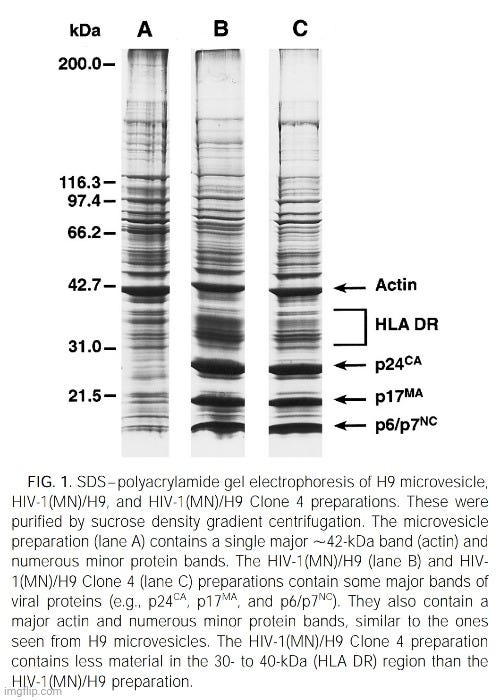

Reaffirming what Gallo stated, the March 1997 paper Cell membrane vesicles are a major contaminant of gradient-enriched human immunodeficiency virus type-1 preparations by Pablo Gluschankof, the leader of a large European HIV research collaborative, acknowledged that in none of the studies using cell culture samples claimed to contain HIV—prepared via centrifugation through sucrose gradients for biochemical (RNA/DNA) and serological (antigen and “antibody”) analyses—“has the purity of the virus preparation been verified.” The team analyzed gradient-enriched “virus” preparations and found significant contamination with an abundance of “non-viral” membrane vesicles of cellular origin (microvesicles) containing cellular membrane proteins similar to those attributed to HIV.

These findings were independently corroborated later that same year by Julian Bess in the paper Microvesicles Are a Source of Contaminating Cellular Proteins Found in Purified HIV-1 Preparations. Bess acknowledged in the very first sentence of the abstract that the identification and quantitation of cellular proteins associated with HIV-1 particles “are complicated by the presence of nonvirion-associated cellular proteins that copurify with virions.” The study confirmed that these microvesicles band in sucrose gradients at the same density as “retroviruses,” and Bess admitted, “we have been unsuccessful in separating microvesicles from HIV-1 by centrifugation techniques.”

This led to the conclusion that proteins thought to belong to HIV might, in fact, be normal cellular proteins originating from these co-purified microvesicles. As Bess explained:

“Since cellular proteins bound to nonviral particles (i.e., microvesicles) can copurify with virus, the finding of cellular proteins in the purified virus preparations does not indicate that these proteins are necessarily physically associated with the virus particles.”

As noted by the Perth Group, the terms “major contaminant,” “contaminating cellular proteins,” and “copurify,” as used in the Gluschankof and Bess papers, are fundamentally incompatible with the claim of “purified HIV-1 preparations.” The Perth Group also highlighted an important observation: a protein electrophoresis of both the “infected” and “uninfected” cultures showed identical protein profiles, including proteins said to be specific to HIV, differing only in quantity.

“The Bess paper included a protein electrophoresis of “HIV-infected” and noninfected density gradient purified material. If the “HIV-infected” material contains a retrovirus HIV as well as cellular material (microvesicles) then, compared to the non-infected material, it must contain the extra 15 proteins said to constitute the HIV virions. However, the Bess data show there are no extra proteins. Apart from quantitative differences in three of the proteins which Bess labelled p6/7, p17 and p24 in the “HIV-infected” material (B&C), the protein profiles of B & C and the uninfected preparations (A) are identical. If there are no extra proteins there are no HIV proteins. If there are no HIV proteins there is no HIV. The particles labelled “HIV” are nothing but cellular microvesicles.”

In email correspondence with the Perth Group, Bess himself acknowledged this point:

“We agree that you can come to the conclusion from gel electrophoresis patterns that there are only quantitative differences between HIV and microvesicles [cellular debris].”

This admission is significant. If there are only quantitative differences between the “infected” and “uninfected” preparations, then there are no proteins specific to HIV. As the Perth Group argued, if no specific HIV proteins exist, Bess and others must also conclude that there is no HIV. In other words, the particles and proteins identified as “HIV” are indistinguishable from normal cellular microvesicles.

The findings by Gluschankof and Bess are not only crucial because they demonstrate the inability to purify a “virus” from cell culture supernatant, but also because of their damning implications for the entire body of evidence used to claim the existence of any “virus,” let alone the unique “retrovirus” purported to cause AIDS. Without a purified and isolated “virus” to confirm the presence of specific “viral” proteins, any tests developed to identify the “virus” are rendered meaningless, as they could simply be detecting normal cellular proteins.

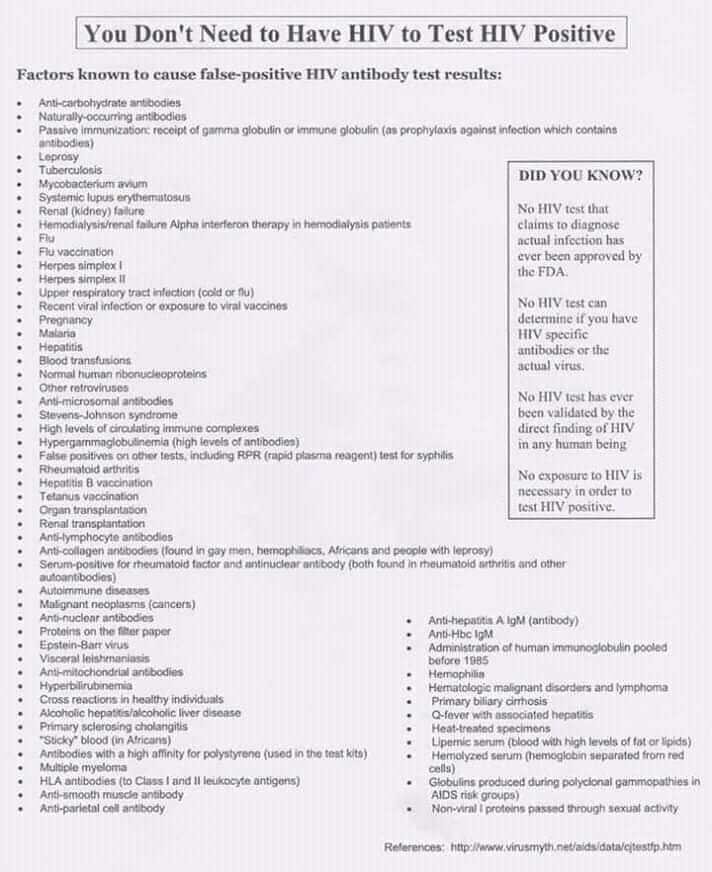

For instance, HIV “antibody” tests are designed to detect “antibodies” specific to HIV proteins. Going against the orthodox view that “antibodies” signify that the body has successfully fought off a “virus,” the CDC adopted the stance in 1987 that the results from these tests were a sign of current “infection,” stating: “The presence of antibody indicates current infection, though many infected persons may have minimal or no clinical evidence of disease for years.” Contradicting this claim are statements from the manufacturers of the “antibody” tests themselves, as noted by the late Dr. Roberto Giraldo:

“Elisa testing alone cannot be used to diagnose AIDS, even if the recommended investigation of reactive specimens suggests a high probability that the antibody to HIV-1 is present” (Abbott 1997).

The insert for one of the kits for administering the Western blot warns: “Do not use this kit as the sole basis of diagnosis of HIV-1 infection” (Epitope Organon Teknika).

The lack of specificity of so-called HIV proteins like p24, gp120, and gp41 means that the results of the “antibody” tests used to claim a positive HIV diagnosis are both fraudulent and meaningless, and that they should not be used for diagnosis. It is known that the nonspecific nature of the proteins targeted by these tests can trigger “false-positive” results due to over 70 conditions, including upper respiratory “infections,” vaccination, kidney failure, blood transfusions, organ transplants, pregnancy, and even “cross-reactions” in healthy individuals.

In 1996, Dr. Giraldo published the article Everybody Reacts Positive on the ELISA Test for HIV, where he detailed his experiences running HIV “antibody” tests over a six-year period. He observed that these tests are conducted using an “extraordinarily high dilution of the person’s serum [400 times],” which surprised him, as most serologic tests typically use undiluted serum. To investigate, he experimented with both diluted and undiluted serum samples from himself and patients considered at risk for AIDS. The results were striking: diluted serum samples consistently tested negative, while undiluted samples always tested positive. Based on these findings, Dr. Giraldo concluded that, under these conditions, everyone would appear to be “infected” with the “deadly virus.”

“I first took samples of blood that, at 1:400 dilution, tested negative for antibodies to HIV. I then ran the exact same serum samples through the test again, but this time without diluting them. Tested straight, they all came positive.

Since that time I have run about 100 specimens and have always gotten the same result. I even ran my own blood which, at 1:400, reacts negative. At 1:1 [undiluted] it reacted positive. I should mention that with the exception of my own blood, the patient samples all came from doctors who requested HIV tests. It is therefore likely that most of the blood samples that I tested belonged to individuals at risk for AIDS.”

“Therefore, the positive reactions of all undiluted sera would mean that everybody, or at least all the blood samples that I have tested, including my own, infected with this “deadly” virus.”

Dr. Giraldo’s observations reveal a significant problem with the non-specificity of the HIV proteins used in ELISA tests. This non-specificity raises doubts about the reliability of the test as a diagnostic tool for HIV. Critics like Henry H. Bauer, Ph.D., have drawn similar conclusions, arguing that these tests cannot reliably diagnose disease. Bauer noted that the criteria for a positive result include p41 and p24—protein antigens “found in blood platelets of healthy individuals.” He concluded that these biomarkers are “far from being specific to HIV or AIDS patients,” and that “p24 and p41 are not even specific to illness.” The 2014 paper Questioning the HIV-AIDS Hypothesis: 30 Years of Dissent provides an excellent explanation of the problematic use of such nonspecific biomarkers to claim a person is “infected:”

An example may clarify: if tested in Africa, a WB showing reactivity to any two of the proteins p160, p120, or p41, would be considered positive for HIV. In Britain, the test would be positive only if it showed reactivity to one of these three proteins, together with reactions to two other proteins, p32 and p24 (see mention of p24, above, as occurring in healthy individuals). Therefore, someone whose test reacts to p160 and p120 would be considered HIV-positive in Africa, but not in Britain. A test reaction to p41, p32, and p24 would be considered positive in Britain, but negative in Africa, leading author Celia Farber to comment: “… a person could revert to being HIV-negative simply by buying a plane ticket from Uganda to Australia [or in our example, from Uganda to London” (14), p. 163].

Regardless of the non-specific nature of the proteins used to identify HIV cases, once someone tests positive using an admittedly unreliable test, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is often used to “confirm” the diagnosis from the results of the “antibody” tests. This is also problematic and misleading as, without specific “viral” proteins, the assumption that PCR is detecting fragments of the “viral” genome to “confirm” a “viral” presence collapses. “Viral” proteins are necessary to validate the structure, function, and genetic material of a “virus.” Typically, a “virus’s” genome is sequenced and mapped based on the proteins it is believed to express. However, the absence of specific proteins means there are no definitive biological markers to correlate with the genome of the supposed “virus,” leading to potential misinterpretation of the so-called “viral” genome.

As the Perth Group pointed out, “irrespective of its origin, any RNA or DNA present in a supernatant can be taken up by cells and reverse transcribed.” This suggests that what is being referred to as the HIV genome is likely a mixture of genetic material from contaminating cellular components such as microvesicles and/or cellular debris. PCR then detects tiny fragments, presumed to belong to the HIV genome, fabricated from the unpurified cell culture supernatant. As Kary Mullis, the inventor of PCR, noted, this process is arbitrary.

“PCR detects a very small segment of the nucleic acid which is part of the virus itself…(Two to three hundred nucleotides is usually chosen out of the several thousand [~10K] in the total retrovirus)…There are many sequence variations among the sequences called HIV. The specific fragment detected is determined by the somewhat arbitrary choice of DNA primers used which become the ends of the amplified fragment. They have to be in the sequence for it to be amplified in the first place, but they can be rather a small part of the total sequence. Any one of them can get you classed as what they consider HIV-positive. And due to the tiny amounts of nucleic acid detectable after many cycles of PCR amplification (after 30 cycles one copy will get you about a billion copies) the test is super-sensitive.”

In a 1997 interview, Mullis, who famously described the HIV/AIDS hypothesis as “one hell of a mistake” and asserted that “there is simply no scientific evidence” supporting it, criticized the misuse of his invention. Mullis argued that PCR can detect virtually anything, as very few molecules are entirely absent from the body. He emphasized that amplifying these molecules to such an extent and claiming they have meaningful implications constitutes a fundamental misuse of PCR.

“I think misuse PCR is not quite…I don’t think you can misuse PCR. The results, the interpretation of it, if they could find this virus in you at all, and with PCR, if you do it well, you can find almost anything in anybody. It starts making you believe in the sort of Buddhist notion that everything is contained in everything else. Right, I mean, because if you can amplify one single molecule up to something which you can really measure, which PCR can do, then there’s just very few molecules that you don’t have at least one single one of them in your body, okay. So that could be thought of as a misuse of it, just to claim that it’s meaningful.”

“It’s [PCR] just a process that’s used to make a whole lot of something out of something. That’s what it is. It doesn’t tell you that you’re sick and it doesn’t tell you that the thing you ended up with really was going to hurt you or anything like that.”

Since there are no specific proteins unique to HIV, it becomes impossible to definitively associate the genome fragments detected by PCR with the “virus.” Accurate identification and characterization of a “virus” require a clear correlation between its proteins and genome. As a 1996 meta-analysis noted, the PCR assay “is not sufficiently accurate to be used for the diagnosis of HIV infection without confirmation.” This is supported by an insert that accompanies a very frequently used Roche test for PCR Viral Load that warns: “the Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test is not intended to be used as a screening test for HIV or as a diagnostic test to confirm the presence of HIV infection.” This highlights a significant circular flaw: the PCR test, often used as a “confirmatory” method for unreliable “antibody” tests, itself requires confirmation and cannot be used as confirmation. Consequently, interpreting PCR test results as definitive evidence of a “viral infection” that will lead to disease is not only misleading but also fraudulent.

Another significant finding in the Gluschankof and Bess papers was that the electron micrographs of the “purified” samples clearly showed more than just the presumed HIV particles. Both researchers published electron microscope images of two density gradient-purified culture supernatants from “HIV-infected” cultures and one from “non-infected” cultures. According to Gluschankof, their “purified” HIV preparations were contaminated with cellular vesicles and other empty, membrane-bound structures, ranging in size from approximately 50 to 500 nm.

“We therefore decided to investigate the possibility that cellular material containing HLA-DR, and perhaps other molecules of cellular origin, might be a contaminant of sucrose gradient ‘‘purified’’ virus preparations. Indeed, electron microscopy of the sediments of culture supernatants revealed a high proportion of empty, membrane-bound structure (data not shown).”

Gluschankof concluded that “cellular vesicles appear, at least under the culture conditions used here, to be a major contaminant of HIV preparations enriched by sucrose gradient centrifugation.” He noted that the vesicles “contain a number of molecules of cellular origin, which are similar to, but not identical to, those found in the virus envelope.” This suggests that these vesicles could potentially be mistaken for the “virus,” or even be the “virus” itself. As a result, particles assumed to be HIV may not actually be “viral.” Without properly eliminating these contaminants from the sample, laboratory techniques could misinterpret these vesicles as “viral” particles, leading to erroneous conclusions about the presence of a “virus,” its characteristics, or its role in causing disease.

The electron micrographs of “purified” HIV presented by Bess also revealed microvesicles consisting of particles with various sizes and morphologies. As noted by the Perth Group, the objects designated as HIV in the images had an average diameter of 234 nm. None of the HIV particles measured less than 160 nm, which means that the particles could not be classified as a “retrovirus,” as “retroviruses” are said to range from 80-100 nm. When questioned about this discrepancy, Bess acknowledged that the particles did not match the size of a “retrovirus,” but he was unable to provide an explanation for why this was the case. The fact that these so-called “purified” preparations contain contaminants has practical implications. As noted by Bess, human cellular antigens have been found associated with HIV preparations, and these were initially recognized as a source of false positives in immunoassays that used “purified” HIV preparations to detect anti-HIV “antibodies” in human plasma samples. This is a damning statement that ultimately undermines the accuracy of the tests designed using impure materials containing cellular contaminants.

The Perth Group also noted that, in the only electron microscopy study—whether in vivo or in vitro—in which suitable controls were used and where extensive blind examination of both controls and test material was performed, “virus” particles morphologically indistinguishable from “HIV” were found in 18/20 (90%) of AIDS cases and in 13/15 (88%) of non-AIDS-related lymph node enlargements. The 1988 study stated that none of the patients in the non-AIDS group, where the “morphologically indistinguishable” HIV-like particles were observed, had risk factors for developing AIDS or exhibited clinical evidence of “immune” deficiency. The fact that “viral-like” particles were found in non-AIDS individuals without HIV “infection” was considered of major significance. Even more troubling for the HIV narrative was that, despite “thorough and fastidious examination,” the cored particles were difficult to find in the majority of cases from both groups.

This observation aligns with what Montagnier said about his research, indicating that it was difficult to find the particles that he believed were the “virus:”

“We saw some particles but they did not have the morphology typical of retroviruses. They were very different. Relatively different. So with the culture it took many hours to find the first pictures. It was a Roman effort!”

The particles that Montagnier did claim to find were not from purified samples. In a December 2005 interview, Djamel Tahi asked Charles Dauget, the Pasteur Institute electron microscopist and one of the co-authors of the 1983 Montagnier paper, how long he had searched in purified gradients before finding the first images of the “virus.” Dauget candidly replied, “We have never seen virus particles in the purified virus. What we have seen all the time was cellular debris, no virus particles.” In 2010, Ettiene de Harven—the scientist who “produced the first electron micrograph of a retrovirus”—confirmed the frequent contamination of “purified” HIV cultures, stating that there are no images of HIV coming from an AIDS patient. All images come from the impure cell cultures:

“This is of considerable importance because attempts to isolate and purify HIV by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation of supernatant from supposedly HIV-infected cell cultures have provided samples heavily contaminated with microvesicular cell debris, readily demonstrated by EM.”

“All the images of particles supposedly representing HIV and published in scientific as well as in lay publications derive from EM studies of cell cultures. They never show HIV particles coming directly from an AIDS patient.”

What this electron microscopy evidence ultimately brings us back to is failing Koch's first postulate, which states that the microbe should be found in abundance in those with the disease. It also contradicts Koch's stipulation that the microbe should not be present in cases of other diseases. While the researchers of the 1988 paper ultimately concluded that the “viral” particles observed in PGL lymph nodes in the AIDS group “were most likely HIV,” they had to concede that similar particles were seen in reactive lymph nodes not associated with HIV “infection.”

“The results of this study compel us to conclude that, while the particles observed in PGL lymph nodes are indeed HIV, morphologically similar particles can be seen in other reactive conditions, and the presence of such particles do not, by themselves, indicate infection by HIV. Clearly, techniques that demonstrate the presence of specific viral antigens or viral RNA are needed to supplement ultrastructural observations.”

These various sources demonstrate that electron microscopy and subsequent protein analyses reveal that “purified” preparations of HIV from cultures are far from being purified and isolated “viral” particles. These papers show that the purification procedures fail to adequately isolate the presumed “virus” particles from other cellular contaminants present in cell culture supernatants. As a result, electron microscope images cannot definitively prove that the particles labeled as HIV are the “virus,” as any of the cellular contaminants could be the actual culprit.

The presence of confounding variables introduced by these cellular contaminants undermines the reliability of the findings. Even leading HIV researchers have admitted that the “virus” has never been fully purified or isolated, whether directly from the fluids of an AIDS patient or from cell culture supernatants. As such, the 1988 study emphasized the need for specific antigens or “viral” RNA to confirm findings. However, this is impossible without first purifying and isolating the presumed “viral” particles to determine what components specifically belong to them.

This lack of true purification, combined with the contamination of cellular components and the non-specificity of the resulting “viral” proteins and particles, exposes the fraudulent nature of using indirect methods to claim HIV's existence. As noted by Koch, having a pure sample of the microbe is the foundation for all research on “infectious” diseases. Without this, the attempts to satisfy Koch's second postulate through in vitro culture, PCR amplification, and “antibody” titers, as noted by O'Brien and Goedert, fail in every conceivable way.

3. The cultured microorganism should cause the exact same disease when introduced into a healthy subject.

4. The microorganism must be reisolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

“Definite evidence will require an animal model in which such viruses could induce a disease similar to AIDS.”

-Luc Montagnier

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6143082/

Dr. Victoria A. Harden: You did not believe that you had to demonstrate that this virus would cause AIDS in some other species. You could not use humans obviously.

Robert Gallo: Exactly. My position has been unchanged from the beginning to now. I think it has been misinterpreted here and there in news articles, but my position has not altered.

https://history.nih.gov/display/history/Dr+Robert+Gallo+Interview+02+November+4+1994

In 1884, while investigating the cause of cholera, Robert Koch stated that the “only possibility of providing a direct proof” that his comma bacilli was the cause of cholera was through animal experiments. He asserted, “One should show that cholera can be generated experimentally by comma bacilli.” This statement aligns with the scientific method, which requires that the hypotheses proposing a cause-and-effect relationships is tested through experimentation for confirmation or rejection.

Luc Montagnier echoed this principle nearly 100 years later, asserting that the only way to prove HIV as the cause of AIDS was to develop an animal model that recreates the disease. However, Robert Gallo dismissed this necessity, failing to demonstrate that HIV could cause AIDS in other species. Why did Gallo feel that an animal model was unnecessary?

The likely reason, as noted by the Perth Group, is that no animal model demonstrating a “retrovirus” causing AIDS had ever been successfully established. Professor Peter Duesberg emphasized that experiments with “pure” HIV failed to reproduce AIDS when inoculated into chimpanzees or accidentally into healthy humans—violating Koch’s third postulate. A 2002 BMJ paper further criticized the failure of animal models, stating that they had been “notoriously inaccurate” and had yielded little, despite significant investment.

To this day, there is no single animal model for AIDS, primarily because it is stated that HIV does not efficiently replicate in any non-human host. A 2009 review acknowledged that AIDS research has been hindered by the absence of an animal model using HIV as the challenge “virus.” Similarly, a 2012 Nature review identified the lack of an animal model replicating all features of HIV “infection” as a major limitation in finding cures and vaccines. Attempts to “infect” smaller animals like mice, rats, and rabbits with HIV have been unsuccessful, while experiments with larger animals like chimpanzees failed to induce disease despite HIV “infection.”

In response to this impasse, researchers turned to genetically modifying animals or using unrelated animal “viruses” to create models. For instance, “humanized mice”—immunocompromised mice engrafted with human tissues—are considered the best small-animal models for HIV/AIDS. However, these mice live in sterile environments and do not require functional “immune systems” to survive, failing to replicate the fundamental aspects of HIV pathogenesis.

For larger animals like non-human primates, models typically use simian immunodeficiency “viruses” (SIVs) or hybrid “viruses” (SHIVs) that are claimed to be related to HIV. However, these models face significant limitations due to the purported large genetic differences between SIV and HIV. Ironically, it is stated that SIVs naturally “infect” many African monkeys and apes without causing disease, further undermining the model’s relevance. While SIV and SHIV “infections” in macaques have been a mainstay of AIDS research for over 20 years, the “viruses” are said to differ significantly from HIV, making any extrapolation to human disease misleading and scientifically unsound. As the 2012 Nature review concluded, it may be impossible for any animal model to fully replicate the features of human HIV “infection.”

Despite the inability to establish a successful animal model using purified and isolated HIV to induce AIDS, researchers like O’Brien and Goedert continue to assert that Koch’s third and fourth postulates have been fulfilled. While they concede that “the postulate of transmission pathogenesis cannot be fulfilled by epidemiological data, but instead requires direct empirical evidence,” they rely on epidemiological data and indirect evidence to make their case. Their argument includes two human examples and three animal models, all of which fail to provide direct experimental proof of causation.

The first human example involves three laboratory workers allegedly “infected” with HIV, and the second references the 1990 case of Dr. David Acer, a dentist accused of “infecting” his patients. Both cases rely on dubious methodologies, including fraudulent “antibody” tests, unreliable CD4 counts, and unproven genomic data, to claim HIV “infection.” These examples fall short of experimental proof and cannot substitute for direct evidence of causation.

O’Brien and Goedert also present three animal examples. The first involves HIV-2, said to be a less pathogenic and genetically distinct strain, “infecting” baboons. Only three of five baboons exhibited CD4+ cell depletion and vague “AIDS-like” pathology, making the findings inconsistent and inconclusive. Furthermore, using a sample claimed to contain HIV-2 as a stand-in for HIV-1 is misleading and fails to meet the rigor required by Koch’s postulates.

The second example employs SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency) mice, which are genetically engineered to lack functional B and T lymphocytes. Implanting human fetal lymphoid tissue or peripheral blood lymphocytes (hPBLs) into these mice creates an artificial and incomplete model of the human “immune system.” While CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion is reported after HIV inoculation, this does not replicate the systemic symptoms of AIDS, such as opportunistic “infections” and cancers. The artificial nature of this model undermines its relevance to human HIV/AIDS pathogenesis.

The third example involves simian immunodeficiency “virus” (SIV) in monkeys. As previously stated, SIV is said to be genetically distinct from HIV, and the conditions observed in monkeys differ from human AIDS. Claims of SIV-induced AIDS are based on CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion and certain opportunistic “infections,” yet these findings rely on artificial processes. Experiments with SIV culture samples only induces AIDS-like conditions in macaques after being cultured in adapted cell lines and transferred as tissue culture supernatant. This use of unpurified fluids fails to mimic natural “infection” or transmission pathways, rendering the model inadequate.

Interestingly, the (failed) examples supplied by O'Brien and Goedert were not included by TheBody.com article, which claimed that the third and fourth postulates of Koch’s framework were satisfied by citing a 1997 study by Francis J. Novembre, Ph.D., and colleagues at Emory University, published in the Journal of Virology. The article asserted that the study demonstrated a chimpanzee inoculated with HIV ten years earlier had developed an AIDS-defining opportunistic “infection” (OI). It cited an increase in HIV “viral” load and a decrease in CD4+ cell count prior to the OI as evidence of AIDS development. However, the article omitted critical context that undermines this conclusion.

The chimpanzee had been subjected to multiple experiments over the years, including three separate inoculations with different HIV-1 cell culture “isolates”—HIV-1SF2 in 1985, HIV-1LAV in 1986, and HIV-1NDK in 1987. Aside from the lack of exposure to a purified and isolated “virus,” the use of multiple cultures introduces ambiguity, as it is unclear which, if any, of these “isolates” contributed to the observed pathology years later. Without isolating and purifying a single specific “virus,” it is impossible to determine causation or attribute the outcome to any particular “isolate.”

The study also claimed that cultures of blood from the animal tested positive for HIV and used this to assert that the same “virus” had been recovered. However, using indirect tests to “detect” a “virus” is not equivalent to purifying and isolating the “virus” from the diseased host, a requirement of Koch’s fourth postulate.

The article further argued that Koch’s postulates were satisfied when blood from the “infected” chimp was transfused intravenously into a second healthy chimp, which subsequently exhibited an increase in HIV “viral” load and a decrease in CD4+ cell count. However, this claim fails for several reasons:

Blood Transfusion vs. Purified “Virus:” The transfused blood was a complex mixture of biological components (PBMCs, plasma, and other substances), and the presence of the “virus” was assumed rather than demonstrated. This does not meet the requirement of isolating and purifying the pathogen.

Unaccounted Alternative Causes: The sharp decline in CD4+ T cells could have resulted from factors unrelated to a “virus,” such as “immune” reactions to foreign blood cells or a stress response from the transfusion itself. These possibilities were not ruled out.

No Development of Clinical AIDS: The second chimp did not develop clinical AIDS. Despite a drop in CD4+ T cells, the animal exhibited no weight loss, lymphadenopathy, anemia, or other symptoms indicative of AIDS. The only reported symptom was an episodic rash, which is nonspecific and does not establish HIV pathogenesis.

Divergent “Virus” from the Original: The researchers confirmed that the “virus” recovered from the initially inoculated chimp showed significant divergence from the inoculated strains. Koch’s fourth postulate requires that the pathogen recovered from the diseased host be identical to the one originally introduced. This divergence undermines the claim that the same “virus” was responsible for the observed effects.

Clearly, unlike what the TheBody.com article tried to sell, the 1997 study fails to satisfy Koch’s third and fourth postulates. It does not establish causation between the purported “virus” and disease, nor does it provide direct evidence that HIV alone causes AIDS. The reliance on ambiguous experimental setups and indirect detection methods further weakens the claims.

No matter how one looks at it, HIV fails to satisfy Koch's third and fourth postulates due to the lack of a suitable animal model that recreates the disease. In light of the challenges faced in studying HIV/AIDS, researchers have attempted to sidestep the rigidity of these postulates, as seen in a 2017 journal article.

“Animal research was fundamental in proving the etiology of a disease according to Koch’s postulates, which for the latter 19th and early 20th centuries were considered to be essential for proving the cause of a disease (reviewed in Madeley 2008). Until the discovery of AIDS, reproducing the disease in an animal model and being able to re-isolate the agent from a laboratory animal with the same disease signs was considered necessary to prove causality. It was eventually recognized these rules may not apply to all pathogens, because of complicated molecular events of host pathogen interactions that we are only now beginning to understand.”

Ironically, while trying to bypass this necessity, the authors clearly acknowledge its importance, calling the recreation of disease in animals “fundamental” to proving the etiology of disease through Koch's Postulates, which were crucial for establishing disease causation. Establishing an animal model was considered essential until AIDS came along, and researchers were unable to do so. As a result, the rules were bent to allow for a causal relationship without fulfilling the core criteria for causation. Indirect evidence had to suffice as, pointed out by O'Brien and Goedert: “Ethical consideration precludes experimental transmission to uninfected human patients, making verification difficult.”

However, despite the excuses and concerns, there is evidence of an attempt at direct transmission in humans that refutes the causality claim. Dr. Robert Wilner, unconstrained by ethical considerations, injected himself with the blood of an HIV-positive patient during a live television broadcast (starting around the 40-minute mark). Despite this dramatic demonstration, Dr. Wilner remained healthy, never tested positive for HIV, and did not develop AIDS.

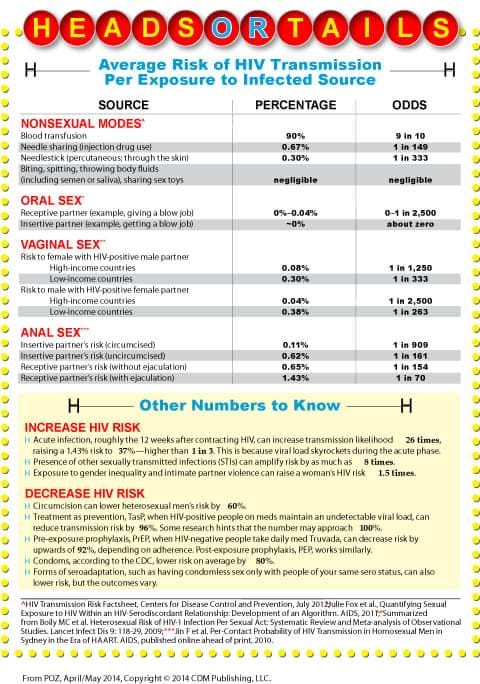

While evidence from a single individual willingly injecting himself with the blood of an HIV patient does not adhere to Koch's Postulates—since it does not use a purified microbe—it does help to falsify the hypothesis that the blood of an HIV+ individual invariably causes disease when injected into a healthy person. Further supporting this point are admissions from the CDC regarding how extremely difficult it is for healthcare workers exposed to “HIV-infected” blood to become “infected.” The CDC has stated that “transmission of HIV to patients while in healthcare settings is rare” and that “most exposures do not result in infection,” even calling such occurrences “extremely rare.”

From 1985 to 2013, there were only 58 “confirmed” occupational HIV “transmissions” to healthcare personnel, with just one occurring after 1999. The CDC also notes that healthcare workers exposed to needlesticks involving “HIV-infected” blood have an estimated 0.23% risk of becoming “infected.” Moreover, the risk from exposure to body fluid splashes is believed to be near zero, even if the fluids are visibly bloody. Fluid splashes to intact skin or mucous membranes are considered to pose an extremely low risk of “HIV transmission,” regardless of whether blood is present.

For exposures of non-intact skin to “HIV-infected” blood, the estimated risk is less than 0.1%, while a small amount of blood on intact skin “probably poses no risk at all.” In fact, the CDC states there have been no documented cases of HIV transmission involving small amounts of blood on intact skin, such as a few drops for a short period of time.

This evidence is compelling, as it demonstrates that direct contact with “infected” blood, even through a needlestick injury, rarely results in “infection” or disease. While this information undermines the HIV “infectiousness” narrative, additional inconsistencies from the CDC further weaken it, including:

A 0.67% chance of “infection” from sharing a needlestick.

A 0% to 0.04% chance of “infection” from oral sex.

A 0.08% to 0.30% chance of “infection” for females during vaginal sex with an HIV-positive male partner.

A 0.04% to 0.38% chance of “infection” for males during vaginal sex with an HIV-positive female partner.

A 0.11% to 1.43% chance of “infection” from anal sex, depending on circumcision status and ejaculation.

These already-low transmission rates are further complicated by additional dubious claims:

Gender-based differences in risk: Men (1 in 2500) and women (1 in 1250) purportedly have different odds of being “infected.”

Economic factors: The odds of “infection” reportedly vary based on a country’s income level.

Social dynamics: Gender inequality and intimate partner violence are said to increase a woman’s risk of HIV, though the mechanism for this is unclear.

Circumcision: Circumcision is claimed to reduce a male’s risk of “infection,” yet the biological justification remains contentious.

The information provided by the CDC suggests that it is remarkably difficult to become “infected” with HIV through direct contact with the “virus,” whether via needlestick injuries, sharing needles, or sexual intercourse. This difficulty is further supported by the findings of the infamous Padian study from 1997, which followed 176 discordant couples (one HIV-positive partner and one HIV-negative partner) over a period of 10 years. Despite these couples regularly engaging in unprotected sex, the researchers observed no seroconversions among the HIV-negative partners during the study period.

The study estimated an “infectivity” rate of approximately 0.0009 per contact for male-to-female transmission and an even lower rate for female-to-male transmission. These astronomically low rates of “infection” underscore the researchers’ inability to demonstrate transmission of the “virus” from an “infected” partner to an “uninfected” partner during the study period.

What this ultimately means is that there is no direct experimental evidence using purified and isolated “virus” obtained from the fluids of a sick host that causes a healthy host to develop AIDS after exposure. Additionally, the epidemiological evidence does not support the hypothesis of a pathogenic, bloodborne “virus” that can be transmitted through needles or unprotected sexual intercourse. For all intents and purposes, HIV fails to meet both the third and fourth of Koch's Postulates, as it lacks valid scientific evidence to support the claim of causation.

HIV Fails Koch's Postulates

“However, if it can be proved: first that the parasite occurs in every case of the disease in question, and under circumstances which can account for the pathological changes and clinical course of the disease; secondly, that it occurs in no other disease as a fortuitous and non-pathogenic parasite; and thirdly, that it, after being fully isolated from the body and repeatedly grown in pure culture, can induce the disease anew; then the occurrence of the parasite in the disease can no longer be accidental, but in this case no other relation between it and the disease except that the parasite is the cause of the disease can be considered.”

-Robert Koch in 1890, speaking of bacteriological research before the Tenth International Congress of Medicine in Berlin

https://journals.asm.org/doi/pdf/10.1128/jb.33.1.1-12.1937

While Robert Koch occasionally deviated from the core logic of his postulates to try and fit the evidence to his theories in order to keep his findings, fame, and fortune intact, it remains clear that he understood what was necessary to definitively prove that any microbe could cause disease. At the heart of this was the need to isolate and purify the microbe in order to conduct experiments demonstrating causality. Unfortunately for Koch and the bacteriologists that followed him, these logical requirements could not be satisfied in the study of bacterial diseases. As noted in Fields Virology, it was only when these rules “broke down”—meaning they “failed” to yield a causative agent—that the concept of a “virus” emerged.

However, virologists quickly recognized that Koch’s Postulates had not been met in “viral” diseases either. Why? Because there is no ability to isolate, purify, and identify presumed “viral” particles directly from the fluids of an “infected” host prior to experimentation. Without this crucial step, it becomes impossible not only to satisfy Koch's Postulates but also to adhere to the scientific method itself. The independent variable—in this case, the supposed “virus”—must be proven to exist first, and it must be available to vary and manipulate in controlled experimental conditions.

Indirect evidence, such as cell cultures, PCR testing, “antibody” studies, “viral” genomes, electron microscope images, and challenge studies using impure materials injected into animals in unnatural ways, cannot substitute for direct observation and isolation of the “virus.” They cannot replace properly controlled exeriments run in accordance with the scientific method. The methodology of virology falls short of fulfilling the necessary criteria for scientific validation.

HIV exemplifies this failure on every level. It cannot satisfy the initial postulate, as the presumed “viral” cause is “detected”—using unreliable tests—in individuals with other diseases and even in healthy people. Moreover, there are cases of AIDS where the “virus” is absent, such as HIV-negative AIDS or instances where it cannot be cultured in individuals diagnosed as HIV-positive.

HIV also fails the second postulate requiring purification and isolation. The “virus” cannot be directly purified from the fluids of an AIDS patient, and the cell cultures used for “isolation” are demonstrably impure, with normal proteins and cellular particles misinterpreted as the “virus.”