One thing that people may not know about me is that I have a twin brother. I was the “expected” child who popped out of the oven first, and he was the surprise who came out minutes later. We were born before the widespread use of ultrasound, so my parents were left in shock and unprepared for the unexpected arrival. To make matters even more stressful for them, we were also born a few months premature, and very nearly didn't survive the experience. Fortunately, the hospital had an excellent NICU team, and we were both home with our parents and our 3-year-old brother within a little over a month. My twin and I grew up inseparable. In fact, my crib had to be moved next to my brother's as I would constantly try to climb out of mine in order to get into his. We liked the same music, shows, games, hobbies, etc. You name it, and we were pretty much in alignment with what we liked, minor a few slight differences (i.e. Superman for me, Spider-Man for him).

While we liked and shared many of the same things, one thing that we rarely shared were colds. In fact, I can only remember two instances in our lives where we were both “sick” at the same time despite always being together. Once was when we both had mild cases of what was claimed to be chickenpox (2-3 “lesions” each). The other time was in elementary school when I was home sick for a few days with a fever. My brother decided that I was living the good life, and he wanted to be living it as well. We both gave Oscar-worthy performances dialing up our “illnesses” while fudging the thermometer readings using the heat from our night lamps. We missed two full weeks of school just so we could stay home and play video games (sorry, mom 😞).

From my recollection, which I confirmed with my family, there were never any other instances where we were simultaneously sick. There were no times where one of us would have a cold, and then the other would come down with the same symptoms of disease a few days later. Even though I was regularly diagnosed with “highly contagious” strep throat throughout my childhood, both of my brothers seemed to rarely ever come down with the symptoms of disease, or if they did, it was not around the same time that I would be dealing with it or within the alotted “incubation period” afterwards. In fact, I do not recall any times where our older brother was ever sick after one of us experienced symptoms, or any times that my parents ever “caught” the same symptoms of disease from any of us. Even my grandparents, who would come over to care for us when we were not feeling well, never came down with the same illness after being around their sick grandchildren for extended periods of time. Somehow, we all seemed to be “immune” to whatever disease one member of the family was suffering from at a given time.

Regardless, my parents would try to keep us separated from each other when one of us was feeling unwell, and this reinforced the idea that disease could be passed from one kid to the other. However, this was rarely, if ever, the experience in our household. Even with the attempts to keep us separate, we were always together, and exposure to the germs would have been a given. It appeared that we had some sort of super human ability to avoid spreading our illnesses to other members of our family. Thus, the idea of “infectiousness” and “contagiousness” always felt foreign to me. Perhaps this lack of disease “spread” helped me to eventually realize the germ “theory” lies later on in my life.

I acknowledge that this is not the experience for everyone, and there are instances where it appears that disease spreads from one member of a household to another. However, I know that I am not the only one who did not regularly observe “contagion” growing up. For every person that supports the idea of “infectiousness” and “contagiousness” through personal stories of “spreading” disease to other family members, there are just as many stories where people recount how no one in their families became sick with disease while being around those who were. There are plenty of instances where we are around co-workers or in public places with people experiencing disease where we never “catch” whatever it is that they are suffering from. People seem to forget these instances and focus only on the times where they did become sick after being around someone else who was. It then becomes ingrained within their subconscious that they must have “caught” the disease, whether bacterial or “viral,” from the person to whom they were exposed to.

Given my childhood experience, where illness seemed to respect personal boundaries, I started to question the concepts of “infectiousness” and “contagiousness.” If disease can be passed from one person to another, wouldn't it have spread in my own family, especially between me and my twin brother as we were practically inseparable? Is it true that being around those who are sick will result in the same disease occurring in someone else? Can disease really be passed on from one person to another? To answer these questions, we couldn't ask for better subjects to test the hypothesis on than identical twins who are always around each other. Even better yet, studying conjoined twins who are literally inseparable would go a long way towards providing answers.

For those who may be unfamiliar, conjoined twins are those born with their bodies physically connected, a rare occurrence in about one out of every 200,000 live births. These twins are always identical and are most often fused at the chest, abdomen, or pelvis. While they have separate hearts, they often share several internal organs and a circulatory system. In most cases, separation isn’t possible, and unfortunately, many do not survive after birth. Given their close proximity and shared vital organs and bloodstream, one might expect that if one twin became ill with a bacterial or “viral” disease, the other would inevitably contract the same illness around the same time. This scenario would provide strong evidence supporting the germ “theory” of disease. But is it true that conjoined twins are destined to suffer the same “bacterial or viral disease” at the same time? Fortunately, we have accounts from surviving sets of conjoined twins whose experiences with disease may shed light on whether illness can indeed be transmitted from one person to another. Here are their stories.

Masha and Dasha

The first story is the tragic tale of Masha and Dasha Krivoshlyapova, conjoined twins born on January 3rd, 1950, in Soviet Russia during Joseph Stalin’s regime. Shortly after the birth of the girls by caesarean section on a cold winter night, their mother was informed that her daughters had been stillborn. In reality, a false death certificate had been concocted and the twins were secretly taken by Soviet physiologist Pyotr Anokhin to be subjected to horrific experiments under the guise of scientific research. This heinous act was something that was permissible during Stalin’s rule.

For the first six years of their lives, Masha and Dasha were kept in a glass cage, locked away from the world. The cruel experiments inflicted upon them were designed to study the relationship between their shared “immune” system and their separate nervous systems. The so-called “scientists” wanted to explore the body's ability to adapt to extreme conditions, such as sleep deprivation, starvation, and drastic temperature changes. Tragically, the twins were viewed as ideal human guinea pigs for these inhumane investigations.

The girls endured starvation, electrocution, freezing, scalding, and prolonged sleep deprivation, while their blood and gastric fluids were routinely extracted. For instance, one twin would be painfully poked and prodded in order to observe what reaction would be provoked in the other twin. They were also injected with substances like radioactive iodine to observe how quickly it spread between them, with Geiger counters measuring the results. In one particularly heartless test, one twin was packed in ice to see how the other would regulate her own temperature. The experiments were so traumatizing that the girls had to mentally dissociate to survive. With no toys or normal interaction, they invented role-playing games to distract themselves from the unbearable reality of their suffering. Fortunately for the girls, once the “Stalin era” ended, the experiments were terminated.

While much of their early torturous years remains shrouded in mystery, details about Masha and Dasha's post-experiment lives can be gleaned from a few sources. In the 2015 paper A Cinematic and Physiological Puzzle: Soviet Conjoined Twins Research, Scientific Cinema and Pavlovian Physiology, Nikolai Krementsov, PhD told how, after years of enduring agonizing experiments at the Academy of Medical Sciences Pediatric Institute, the girls were sent to a boarding school in 1964. There, they were ostracized and bullied by their peers, which led them into deep depression, and they eventually turned to smoking and drinking as coping mechanisms.

In 1970, the girls ran away from the school to Moscow, where they were given a small disability pension and placed in a retirement home. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that the Russian public learned of their existence, and journalists rushed to tell their story. Although the media attention brought some improvements—such as donations that provided better housing, a new wheelchair, and financial support—it came at a cost. By 1991, the twins became tabloid targets, with sensationalized stories about their alcoholism and personal sex lives dominating headlines. There were also rumors about their father being an associate of Lavrentii Beria, Stalin’s infamous executioner, with some implying that the twins’ condition was karmic “punishment” for his actions.

Despite the media frenzy, Masha and Dasha largely refused interview requests, except from British journalist Juliet Butler, who was granted the opportunity to record the twins’ life stories. This work became the basis for their “autobiography” that was published in 2000. Butler ensured that the sisters received a portion of the royalties, which helped improve their financial situation. However, the years of physical and mental abuse had taken their toll on the girls’ health. On April 17th, 2003, Masha passed away from a heart attack. Dasha, unaware of her sister’s death, was told that Masha was simply sleeping. Sadly, Dasha was slowly poisoned by the cadaver’s toxins that had begun decomposing Masha’s body which had passed into her bloodstream. Seventeen hours later, Dasha also passed away, bringing a tragic end to the lives of the conjoined twins who had been the subject of cruel scientific fascination.

What we know with more or less certainty is this. Masha and Dasha were born by caesarean section on January 4, 1950, in a Moscow hospital, to Ekaterina and Mikhail Krivoshliapovs. The parents were told that the twins died at birth.[43] The next seven years of their life in the Institute of Pediatrics are documented in the 1957 film. On camera, they seem happy and thriving, enjoying the attention they were getting from the scientists, nurses, teachers, and filmmakers. Yet every simple thing (such as sitting or standing) was a struggle. Doctors from the Central Institute of Orthopedics designed a special program of training and exercise to help the sisters develop necessary motor skills. It took Masha and Dasha almost two years, but, as shown in the film, by the age of seven they had learned how to walk using crutches and even to ride a tricycle—no mean feat given that each twin had a complete control of one leg, but no control of the other. Sometime in the early 1960s, the twins’ third vestigial leg (clearly visible in the film) was amputated. Along with the development of necessary motor skills, the sisters were schooled in all the subjects of a Soviet primary school curriculum (reading, writing, math, etc.).

Then, suddenly, their life at the Institute of Pediatrics came to an end. In 1964 Masha and Dasha were sent to a special boarding school for disabled children in Novocherkask (the very city where Anokhin had begun his career as a Bolshevik).[44] According to the twins’ recollections, recorded some thirty years later, the school turned out to be a living hell. Their classmates shunned and bullied them. Masha and Dasha took up drinking and smoking (Masha preferred the latter, Dasha the former). With the help of Nadezhda Gorokhova, a physical therapy nurse who had cared for them at the Institute of Orthopedics, they “ran away” from the school and came to Moscow in 1970. For a year they stayed with the nurse. Finally, after overcoming numerous bureaucratic hurdles (one of which was getting two separate passports), the sisters were given a very small disability pension (sixty rubles a month for both of them) and placed in a “retirement home” on the outskirts of Moscow. Even though some individuals, including Anokhin, tried to help Masha and Dasha adjust to their “independent” life, the sisters largely kept to themselves to avoid the morbid curiosity and sordid proposals of nosy strangers. Alcohol became their constant companion, a not very fulfilling escape from the poverty, loneliness, emptiness, and sadness of life.

In the late 1980s, in the heyday of Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost’, the Soviet public finally learned about the twins’ existence. A group of journalists, including Irina Krasnopol’skaia, a science correspondent of the popular daily Moscow Truth, Vladislav Listyev, the producer and anchor of the most popular “perestroika” TV program “Glance” (Vzgliad),[45] and Valerii Golubtsov, a correspondent of the Soviet News Agency (APN), reported on Masha and Dasha’s dismal existence and appealed to the public for help.[46] The appeal bore some fruit, helped the twins obtain better housing and financial assistance. A special bank account was set up for cash donations.[47] Several individuals provided household items and clothing. A certain “Mr. Maier” brought the sisters a specially designed wheelchair.[48]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the rapidly “yellowing” Russian press made Masha and Dasha notorious. Tabloids had a field day with the stories of the twins’ alcoholism and sex life and alleged that their father had worked as a personal driver of Lavrentii Beria, Stalin’s most infamous executioner, implying that the sisters’ birth had been “proper punishment” for Beria’s associate. The highlight of their life in the early 1990s was a short visit to Germany. The sisters were deeply impressed: they stayed in an ordinary hotel, ate at ordinary restaurants, went everywhere they wanted. Nobody stared at them! They were treated as “ordinary persons.”[49] Back in Russia, Dasha fell into deep depression, which she fought with the familiar medicine—alcohol.[50] Journalists kept pestering the twins with requests for interviews, but for the most part the sisters refused. They made an exception to Juliet Butler, a British journalist stationed in Moscow, who recorded Masha’s and Dasha’s recollections of their life. These recordings provided the foundation for the sisters’ “autobiography” written by Butler and published in early 2000 in German and Japanese.[51] Butler arranged for the sisters to get a portion of the royalties from the sale of the book. In October 2000, she was instrumental in getting Masha and Dasha featured in a special episode devoted to conjoined twins on the BBC2 documentary series Horizon.[52] Their financial situation improved, but it did little to break the vicious circle of loneliness, isolation, and heavy drinking. The sisters’ health began to deteriorate. In April 2003, Masha died of a cardiac infarction. Seventeen hours later, Dasha followed.[53] At the time of their death, Masha and Dasha were said to be the oldest living conjoined twins in the world.

Why bring up such a heartbreaking tale of two tortured souls? The twins were considered a biological marvel, with each girl having her own lungs, heart, stomach, kidneys and small intestine, while sharing a large intestine and bladder. A third leg, which consisted of two fused legs with nine toes, was eventually amputated, leaving the girls troubled and enormously self-conscious until they eventually learned how to move around with the aid of crutches. The girls were linked together not just in an obviously physical manner, but also in other ways as well. According to a 2021 story in Russia Beyond, they “shared identical dreams; when one drank, the other got drunk and when one ate her fill, the other also felt full; when one was receiving dental treatment, the other felt pain and nausea as the anesthetic wore off; when one began to think of something, the other would continue the thought.” In other words, the girls were bound together in numerous profound ways.

However, there was one suprising way in which the girls were not seemingly connected. When one twin was suffering from a disease claimed to be bacterial or “viral,” the other twin would remain completely healthy. This was demonstrated by an experiment performed when the girls were just three years of age. At this time, they were held in ice for a long period. One of the twins ultimately came down with the symptoms of pneumonia with her body temperature reaching 40°C. Interestingly, the other twin had no symptoms whatsoever, and her temperature did not rise above 37°C. Since the girls circulatory systems were interconnected, they shared the same blood, meaning any bacterium or “virus” that would enter one twin’s bloodstream would also be present in the other twin as well. Yet, the girls never shared disease such as the flu, colds, and other childhood diseases as these were all experienced separately. Even the “highly contagious” measles “virus” proved ineffective as one twin came down with the symptoms of measles while the other did not.

The explanation given for why one of the twins could remain healthy while the other was dealing with a “pathogen” was that they had separate nervous systems. However, the nervous system is not typically understood to play a direct role in determining whether “pathogens” like bacteria or “viruses” affect individuals differently—especially when those pathogens are circulating in a shared bloodstream. According to the conventional understanding of “infectious” disease, if a pathogen is present in the bloodstream, both individuals sharing that circulatory system would be exposed to the same pathogen and, theoretically, should succumb to the same disease around the same time. While their separate nervous systems might influence how their bodies respond to stress or other factors, it would not prevent exposure to blood-borne pathogens or any resulting illness. Therefore, the fact that the twins did not get sick at the same time suggests that, even when two individuals are exposed to the same internal environment (such as the bloodstream), they may respond differently, indicating that the mere presence of a “pathogen” is not sufficient to cause illness. This story highlights the importance of environmental factors and psychosomatic components in the development of disease, and drives a dagger into the heart of the germ “theory.” While the experiences of Masha and Dasha are powerful evidence contradicting the prevalent paradigm, their story isn't the only one.

Abby and Brittany

The story of Abby and Brittany Hensel is far less tragic than that of Masha and Dasha, and it is still being written today as the girls are only 34 years of age, making them the oldest dicephalic conjoined twins living. At the time the girls were born on March 7th, 1990, no one knew that their mother, Patty Hensel, would be having twins, let alone conjoined twins. The ultrasounds regularly showed a single fetus with one head, with doctors later concluding that the two heads must have been perfectly aligned every time an ultrasound was performed in order not to be detected. The father of the girls, Mike Hensel, did admit that he had heard two heartbeats during one sonogram, but his observation was dismissed at the time. Patty underwent a scheduled C-section as doctors thought that the fetus was in the breech position, and the whole room was stunned silent when the conjoined twins were pulled out. They were not expected to survive the first night.

Miraculously, the girls survived against the odds as they had only a 1% chance of making it past the first year of life, with the total survival rate of conjoined twins being 7.5%. While given the option by doctors to separate the two girls, as so many of their organs are shared, their parents never entertained having them separated as it would have likely meant that either one girl would not survive, or they would both be left invalid. “How could you pick between the two?” Mike said, during a 2001 interview with Time magazine. Along with having their own head, each girl has her own heart, stomach, spine and lungs. However, the twins share two arms and legs between them, with Abby controlling their right arm and leg, while Brittany controls the limbs on the left side of the body. They share a pelvis with all of the same organs below the waist as well as the same bloodstream. Never knowing any differently, the girls have thrived living an inseparable life.

The girls successfully learned how to work together in order to excel at running, swimming, basketball, softball, and playing the piano, with Abby taking the right-hand parts and Brittany the left. They even mastered their shared coordination in order to learn how to drive, with Brittany stating, “Abby takes over the pedals and the shifter, we both steer, and I take over the blinker and the lights. But she likes driving faster than me.” Eventually, the girls graduated college and became fourth- and fifth-grade teachers, with a specific focus on math, at Sunnyside Elementary School in Minnesota. Despite their inseparability, the girls do try to maintain their own independence, with each girl able to do some things separately—like sleep, eat, and carry on simultaneous conversations. Like Masha and Dasha, the girls have distinct personalities, with Abby being the more gregarious and outspoken of the two, while Brittany is more "laid back and chill" and has a "weird" sense of humor. Further demonstrating independence, Abby secretly married Josh Bowling, a nurse and US Army veteran, in 2021. The twins emphasize their desire to be treated as two separate people, with Bittany stating in 2007, “We are totally different people.”

As Brittany and Abby are the longest-living dicephalic parapagus conjoined twins ever, and the only known surviving set of twins of this kind, their story gained national attention when they were featured in a 1996 episode of Oprah as well as a LIFE magazine cover story. They went on to star in a documentary called Joined for Life in 2002, followed by a 2003 sequel titled Joined at Birth. They also appeared in a UK television special in 2005 and starred in a reality show, Abby & Brittany, which aired on TLC from August to October 2012. While their remarkable survival story is noteworthy, there is another aspect that makes these girls even more special.

Because their bodies are so closely linked, you might expect Brittany and Abby to always get sick at the same time. But surprisingly, that’s not the case. If one girl catches a stomach bug, the other might not feel a thing. Brittany is more prone to colds, getting the flu more often and at different times than Abby, and has even had pneumonia twice, while Abby has never dealt with those issues. Ironically, the only time the girls have ever complained about being joined was when Brittany was very sick as a child. Abby, healthy as ever, grew bored of staying in bed all day and once wished she could go off on her own. Since then, neither twin has expressed any desire to be separate. Remarkably, their shared circulation allows one twin’s treatment to affect the other; as their mother, Patty, explains, “If Abby takes the medicine, Britty’s ear infection will go away.” Their family doctor, Dr. Joy Westerdahl, who assisted at their birth, notes that the twins only need one set of vaccinations: “They like that they don’t have to get two shots!” Interestingly, while shared circulation allows treatments to benefit both twins, it doesn’t seem to extend to “viruses” or bacteria affecting them equally.

“Despite sharing many of the same major organs, Abby and Brittany have separate immune systems. One of them can be totally healthy while the other one is horribly sick. In fact, Brittany has had pneumonia twice in her life and Abby has never had it.

The twins both agree that being sick is one of the few times they wish they were separated. When Brittany was ill as a child, Abby remembers wishing to be separated after being bored and restless while confined in the same bed as her sick sister. Brittany became so upset by the thought she cried uncontrollably until Abby assured her she wouldn't leave her side.”

As seen, the inability to transmit bacteria and “viruses” between the twins despite their shared circulatory system is often explained away by the concept of an “immune system” rescue device. It is claimed that each girl has her own independent “immune system.” However, given their shared circulatory system, this explanation raises more questions than it answers. If the twins’ blood circulates together, how can each “immune system” operate independently? The shared blood flow would mean that “immune” responses, including the presence of “antibodies” or “immune” cells, would affect both twins simultaneously. This raises doubts about how their “immune systems” could remain completely separate and independently functional, especially when both are supposedly exposed to the same pathogens or treatments. As noted by Dr. Christopher Moir, a pediatric surgeon and medical director at the Mayo Clinic's Children's Center, as the girls share a bloodstream, “You give one a shot and the other is immunized, one catches a cold and so does the other.” However, as demonstrated by the stories of Abby and Brittany, as well as Masha and Dasha, the expectation that one girl would catch a cold when the other does fails to align with reality.

The Others: Challenging the Germ “Theory” Narrative

While Masha and Dasha and Abby and Brittany are among the most well-known examples of conjoined twins who did not experience disease transmission between them, other notable cases demonstrate similar anomalies. These include instances where conjoined twins either failed to share the so-called pathogens or did not confer “immunity” after exposure, despite their shared circulatory systems. Though perhaps not as striking as the previous examples, these accounts challenge other facets of the germ “theory” narrative.

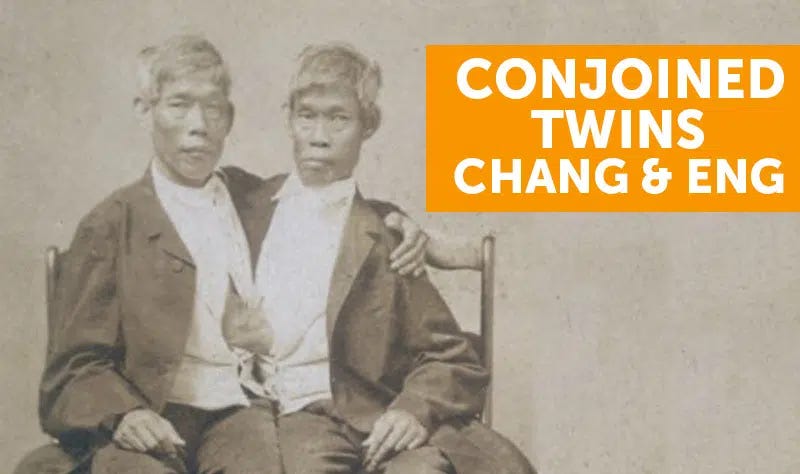

Chang and Eng Bunker

Chang and Eng Bunker, born in 1811 in Siam (now Thailand), were healthy xiphopagus twins conjoined at the sternum by a flexible circular band of flesh and cartilage about 5 inches (130 mm) long with a circumference of 9 inches (230 mm). While each had their own internal organs, their livers were fused at the band, and they shared a connected circulatory system.

The twins rose to fame in the early 1800s as performers, captivating audiences with their acrobatic feats and demonstrations of strength. As part of their act, they would showcase the unique band that physically joined them, which fascinated medical professionals and the public alike. Their popularity grew, and they eventually toured extensively, including with the famous Barnum and Bailey Circus, where they were billed as the "Eighth Wonder of the World."

Similar to Masha, Dasha, Abby, and Brittany, the Bunker twins experienced health issues separately despite being physically connected. After suffering a stroke and partial paralysis in 1870, Chang's health began to deteriorate, while Eng remained unaffected. On January 12, 1874, Chang developed severe bronchitis and chest pains, eventually succumbing to the illness five days later. Eng, who was in good health, was not affected by Chang's condition. However, upon discovering his brother dead, he died three hours later, apparently from shock and fear of meeting the same fate.

An autopsy confirmed that Eng was otherwise in good health. However, an aide of the autopsy, named Nash, felt that Eng bled to death because the flow of blood from Chang to Eng, through the connecting ligament, ceased when Chang died. While Eng’s blood continued to be pumped into Chang, there was no blood pumped back by the dead brother’s inoperative heart, reducing Eng’s blood volume. According to Nash, Eng literally bled to death as the vascular connection between the two may have caused Eng’s blood to drain away over the two to four hours it took for him to die.

“On the voyage across the Atlantic, Chang suffered a stroke and partial paralysis. He recovered partially, but from that time his health began to decline inexorably. It is remarkable that their families managed to endure the strain as well as they apparently did, considering the increasing severity and frequency of the twins' fights. On January 12, 1874, Chang was stricken with severe bronchitis, accompanied by chest pains. The condition grew worse, and he died in his sleep in the early morning of January 17th. Although there was nothing organically wrong with Eng, he was horrified upon waking to find his twin dead, thinking that he would soon follow: they had always regarded themselves as one, signing their names "Chang Eng," rather than "Chang and Eng." A doctor was summoned to try to perform a desperate operation, but Eng died before he arrived. An autopsy conducted in Philadelphia led doctors to conclude that while Chang had died of a cerebral clot brought on by the previous stroke, complicated by pneumonia, Eng had actually died of fright. A partial examination of the connecting band, limited by the family's wish that it not be cut from the front, revealed that their lives were connected by a "quite distinct extra hepatic tract" and that an artery and some nerve connections ran between them; thus, Eng may have suffered from loss of blood from Chang's dying body.”

https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/bunker-eng-and-chang

The shared circulatory system between the Bunker twins should have facilitated the transmission of any supposed pathogenic agents from one twin to the other. Additionally, their constant close proximity should have been sufficient for one twin to expel enough of the pathogenic agent into the nasal passages or lungs of the other. However, as with the previous examples of conjoined twins, this was not the case for the Bunker twins, as diseases were not shared between them.

Despite their tragic end, Chang and Eng left behind a remarkable legacy. They overcame societal and physical challenges, settling in North Carolina, marrying sisters, and fathering 21 children between them. Their story remains a testament to resilience and adaptability.

Ronnie and Donnie Galyon

Ronnie and Donnie Galyon, conjoined twins born on October 28, 1951 in Dayton, Ohio were joined from the sternum to the groin, and had to literally face each other their entire lives. They each had their own heart, stomach, liver, lungs and kidneys, as well as their own set of arms and legs. However, their anatomies were joined at the urinary and lower digestive tracts, with a single rectum and a partially shared bladder which emptied into one penis that Donnie controlled.

The Galyon twins initially rose to fame by spending most of their youth as a travelling circus attraction, performing in sideshows from the time they were small children until their “retirement” in 1991. However, their later claim to fame came as they lived to be 68 years of age before passing away from congestive heart failure on July 4th, 2020. According to the Guiness Book of World Records, this made them the oldest living conjoined twins at the time of their death. Chang and Eng were the previous record holders at 63 years of age.

The Guiness Book of Workd Records also noted that, in 2009, the twins were hospitalized after Ronnie suffered a “viral infection” that resulted in a life-threatening blood clot in his lungs.

“In 2009, the twins were hospitalized after Ronnie suffered a viral infection that resulted in a life-threatening blood clot in his lungs.

They required round-the-clock care afterwards, needing help with almost all tasks, including using the toilet.

An outpouring of donations and volunteers from the local community helped fund and build a handicap-accessible extension to Jim and Mary’s home, where Ronnie and Donnie lived out the remainder of their lives.”

While some sources claim both twins were “infected,” the Guinness account, supported by The Mirror, The Daily Mail, and others, attributes the supposed “viral infection” solely to Ronnie. Despite Donnie not being described as “infected,” both twins suffered from Ronnie's declining health due to their shared circulatory system. Donnie's health complications arose from Ronnie's blood clots, which developed in his legs and left arm, ultimately leading to a pulmonary embolism. This condition can produce flu-like symptoms, which were then attributed to the “virus.”

This situation highlights how shared anatomy in conjoined twins can lead to interconnected health outcomes, even in the absence of the supposed transmission of a “virus.” It also raises an intriguing question: why doesn’t a shared circulatory system more frequently result in the transmission of so-called “pathogenic agents” between conjoined twins, as noted in the previous examples? If the “infection” model were accurate, sharing the same blood should theoretically facilitate the transmission of “pathogens.” However, this does not appear to be the case.

Violet and Daisy Hilton

The Hilton twins' story is both tragic and inspiring. Born in Brighton, England, on February 5, 1908, Daisy and Violet Hilton were conjoined twins rejected by their mother, a barmaid who saw them as a punishment from God for having a child out of wedlock. Left in the care of Mary Hilton, the midwife who delivered them, the twins were exploited for profit. Mary frequently displayed them at local bars, charging curious patrons to view the girls, who were joined at the hips and buttocks, sharing circulatory system but no major organs.

As the twins grew older, they continued to be exploited, first by Mary and later by a corrupt manager in the entertainment industry. Despite these challenges, Daisy and Violet eventually won their freedom and built successful careers as stars of stage, vaudeville, and film. They appeared in notable productions such as Freaks (1932) and Chained for Life (1952), becoming beloved performers in the United States.

However, their fortunes waned after World War II, as the popularity of the vaudeville circuit declined. The twins tried to revive their career by working with a promoter in North Carolina, who arranged appearances at drive-ins screening their films. Tragically, the promoter took off with their earnings, leaving Daisy and Violet penniless, homeless, and stranded. Forced to settle into a quieter life, the twins found work at a local convenience store in 1962. In this new chapter, many customers didn’t even realize they were conjoined.

This semblance of normalcy was short-lived. According to Charles Reid, the now-retired president of the company who hired the Hiltons, in late December 1968, Violet became ill. After recovering shortly thereafter, Daisy followed her sisters illness with what was believed to be the “Hong Kong Flu” said to be circulating at the time. “Violet was the first to get sick," Reid stated. “Just as she started to get better, Daisy caught it.” Daisy's condition worsened rapidly, and she passed away sometime between New Year’s Eve and January 2, 1969.

Despite claims that she was not in any danger as the twins were attached only by skin and not internal organs, Violet, unable to separate from her deceased twin, succumbed two to four days later. On January 4, police discovered the sisters collapsed near their furnace in their rented cottage. It was determined that Daisy had succumbed to the flu, and Violet, lying beside her twin, likely died of starvation or complications from their shared connection.

“Late in 1968, Daisy was diagnosed with the flu which was sweeping the country, but refused hospitalization. On January 4th, 1969, they failed to show up for work at the store. After repeated attempts to reach them, police were called, and the door of their home was forced open. Sadly, the twins were found dead inside, near a furnace vent that they had crawled to in an effort to keep warm. Daisy had succumbed to the flu epidemic first, and it was later determined that Violet had survived for another 4 days lying next to her deceased twin, before she too passed away. Violet had not called for any help…they were together until the end. The twins were 60 years of age.”

If we accept the story that Violet contracted the “virus” first, recovered, and then somehow passed it on to Daisy—who succumbed to it and then “reinfected” Violet, leading to her death—this account presents significant issues. Since the twins shared a circulatory system, the “virus” should have affected both of them around the same time. If Violet was indeed affected first and recovered, according to the germ “theory,” her body should have produced “antibodies” that would have been shared with Daisy, offering her protection. Likewise, if Daisy somehow became “infected,” Violet should also have been protected by the same “antibodies” from her recovery. The shared blood complicates this narrative, as it challenges conventional understandings of “immunity.” If Violet’s recovery involved producing “antibodies,” these should have conferred protection to both twins, yet this seemingly did not occur.

Implications for Germ “Theory”

These cases of conjoined twins present significant challenges to the germ “theory” of disease. The anomalies presented cast doubt on the idea that shared biology and anatomy should result in the consistent spread of diseases between conjoined individuals, or those in close proximity to each other. If pathogens operate as claimed, shared circulatory systems and intimate proximity should provide ideal conditions for disease transmission. Furthermore, according to the official narrative, the recovered twins should theoretically confer “immunity” to their counterparts. Yet, the observed outcomes—isolated illness, lack of transmission, and inconsistent “immunity”—suggest that the narrative of pathogen causation is flawed.

The implications of these cases extend far beyond these extraordinary circumstances. As germ “theory” struggles to explain such clear and controlled scenarios, its broader application to disease causation warrants reevaluation. These stories highlight the need to consider the complexities of human biology, environmental influences, and especially psychosomatic factors in understanding health and disease. The resilience and survival of these conjoined twins underscore the importance of questioning established paradigms and exploring alternative explanations that better account for the diversity of human experiences with illness.

Ultimately, the stories of these remarkable individuals challenge the simplicity of the pathogen-centric model and invite us to embrace a more holistic view of health and disease—one that prioritizes the interplay of physical, environmental, and mental factors over reductionist explanations pertaining to invisible boogeymen.

went biblical on the germ “theory.”The Baileys also wrote an essay for an upcoming book and made an advance video to promote it.

supplied even more excellent Freedom of Information requests from the CDC stating that they have no scientific evidence of feline “viruses” or contagion and no record of a “viral genome.” examined the implications of a Trump presidency and whether his team offers real change or simply more of the same hopium as seen before. challenged the idea of an “immune system” in her latest. broke down the monstrosity that is the polio vaccine.

Great post. What is it Occam's razor? In a sane culture we wouldn't be jumping through all these hoops to try and understand or explain the obvious. There were no piles of bodies in the streets in 2020 because there was no pandemic.

Yep, no immune system but a garbage collection system.

That's why when one died the other went after... No more garbage collection leads to gangrene etc.

https://barn0346.substack.com/p/you-dont-have-an-immune-system