It's a safe bet to say that, at one moment in time or another, we have all reached that level of complete physical and mental exhaustion where we feel that we have reached a breaking point. For some, it is due to being overworked with long arduous hours and seemingly never-ending shifts. For others, it is due to continual sleepless nights after the arrival of a new child. It could be a combination of the two, having to raise one or more kids while juggling multiple jobs and struggling to pay off the ever-increasing debt and monthly bills in order to make the ends meet. The numerous stressors of everyday life may be all that is required to bring us to this moment in time where we feel the need to escape. There are various different scenarios that can occur that will bring about this burning desire within us to get away from it all so that we can have a reprieve. Thus, when the opportunity arises to hit the time-out button so that we can pause our regularly scheduled lives for a moment for a much needed vacation, most of us will jump on and seize the opportunity.

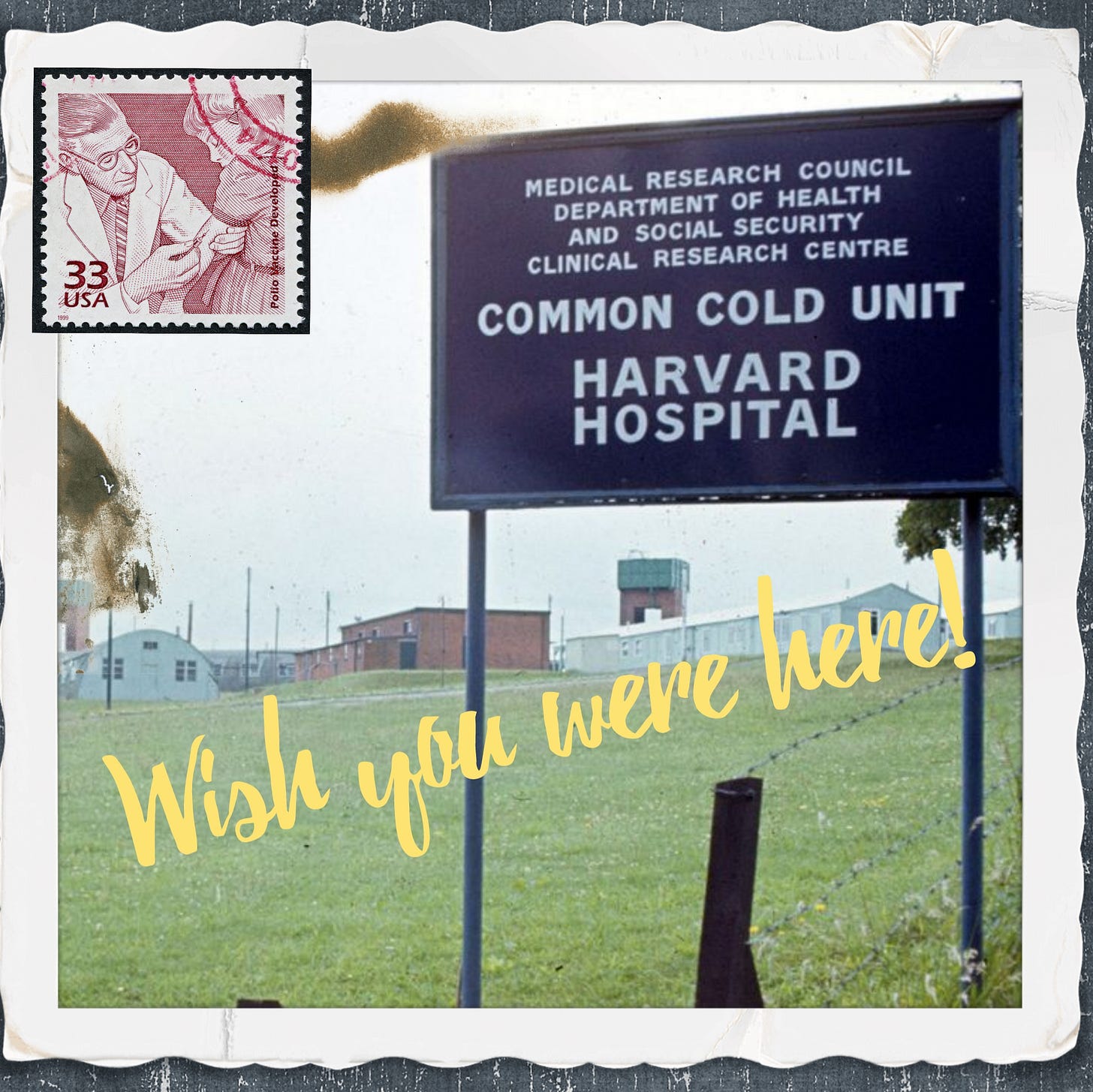

Beginning in the late 1940s, over 20,000 people who needed to get away from the hardships of life were presented with just such a golden opportunity thanks to the Common Cold Unit at Salisbury in Wiltshire. This was due to the desperate need for the researchers to acquire human guinea pigs…er, I mean, volunteers…so that they could study the common cold “virus.” In order to get these volunteers, ads were placed in print promising a cheap and comfortable 10-day holiday where everything was free and people would receive a modest compensation for their troubles. It was sold to the public as the perfect getaway as well as a chance to make a difference, with one ad stating: “Free 10 Day Autumn or Winter Break: You May Not Win A Nobel Prize, But You Could Help Find a Cure for the Common Cold.” Researchers would go on TV and radio promoting the ammentities offered, even targeting honeymooners looking for a relaxing time. All that the volunteers had to do in order to partake in this paid vacation was subject themselves to experiments with fluids which may or may not contain a common cold “virus.” The ads worked, and as stated in a 1982 profile piece in The New York Times, unemployed workers, students writing theses, civil servants using up excess leave, housewives and thrill seekers came calling in order to secure their reservations for a luxurious stay at Salisbury.

This decades-long experiment is where we get our “knowledge” about the common cold from. As it is such an important moment in the history of virology, one that is unlikely to ever be replicated today due to “ethical” concerns, let's examine the origins of this event. Let's investigate what exactly went on at this facility and find out whether they were truly successful in their endeavors. Let's see if we can pinpoint exactly why people were so eager to risk “infection” with a “virus” to the point that the facility was over-subscribed with a waiting list of willing participants excited to have their very own common cold vacation. At the end, it will be clear why these people decided to book return trips to Salisbury over and over again.

The Origin of the Common Cold…Unit.

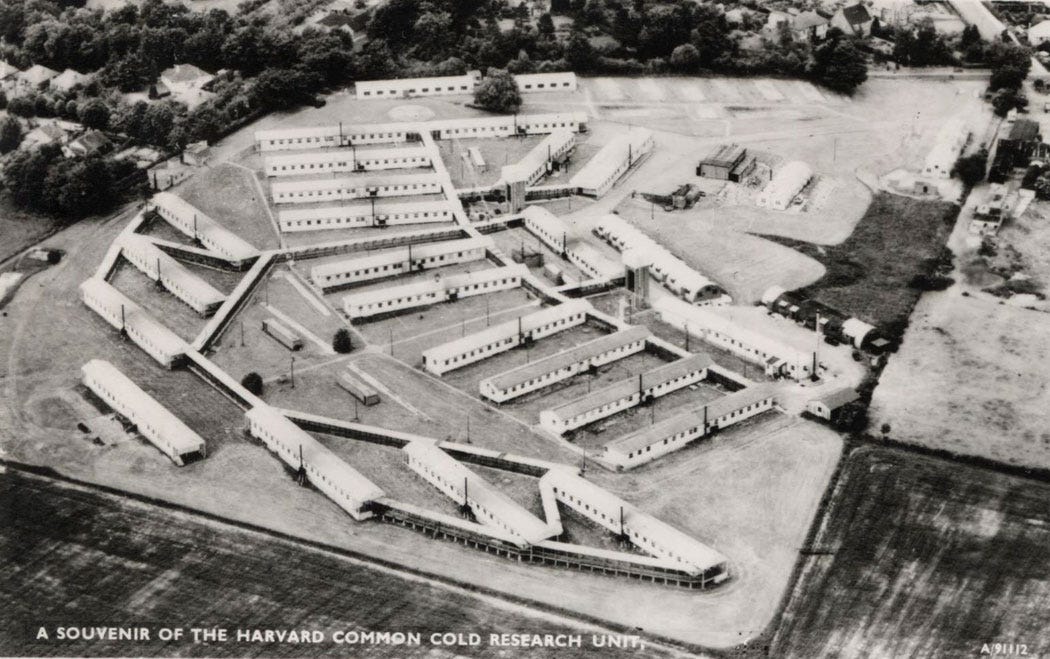

In 1941, during the height of the second world war, Harvard University and the American Red Cross decided to gift to Britain both an epidemiological team as well as a wartime “infectious” disease hospital that it had set up for the British military. According to virologist David Tyrrell, who had worked for the Rockefeller Institute and eventually ran the facility for the majority of its time in operation, funds were raised from individual donors and foundations to send a team equipped to do field studies as well as set up a laboratory and a hospital containing 125 beds to serve civilians. The hospital was planned and its buildings and equipment were said to be ordered “off the shelf” in Washington. It was originally envisioned as a stopgap to deal with feared epidemics of cholera and typhoid outbreaks arising from the bombing of infrastructures during the war. However, the dreaded epidemics never occurred, and from 1942 to 1945, it was given to the US on the premise that the hospital would be relinquished once the war was over. During this time, it was utilized to assemble, store and type the enormous supplies of blood needed for the war effort until it was officially declared over in 1945 and the facility was abandoned.

However, the facility didn't remain abandoned for long as English virologist Dr. Christopher Andrewes, who was working to convince the British Medical Research Council to fund a long term study investigating the common cold and related respiratory diseases, decided that the hospital offered the perfect set-up to undertake such research. Dr. Andrewes approached the Medical Research Council for funds to set up and run a research laboratory, which it ultimately approved for the investigation into the cause of common colds and how they spread. The facility was refurbished and the laboratory was equipped so that the first intake of volunteers were able to arrive in July of 1946.

Although he was successful in establishing his new facility to study the common cold “virus,” there was a bit of a problem for Dr. Andrewes and his team. According to his 1950 paper Adventures Among Viruses. III. The Puzzle of the Common Cold, while their main objective was to find a way of studying the common cold without the use of human volunteers, they could not cultivate or see any “virus.” Dr. Andrewes lamented, “if only we could cultivate and, if possible, see the virus, or produce infection in some convenient small animal,” that it would make them happy, profitable, and busy for dozens of years. Dr. Andrewes pointed out that his crew “have not satisfied ourselves that we can cultivate the virus by any one of many available technics in fertile hens’ eggs.” Not only were they unable to grow any “virus,” the crew attempted - in vain - to produce colds in mice, rats, guinea pigs, cotton rats, rabbits, voles, hamsters, gray squirrels, hedgehogs, ferrets, kittens, pigs, green monkeys, red patas monkeys, capuchin monkeys, baboons and a sooty mangabey. In fact, they attempted to recover “virus” from several species in order to “reinfect” human beings, but this was constantly met without success. Dr. Andrewes admitted that they had, at that time, failed to meet their primary objective.

While he noted that they had not succeeded, Dr. Andrewes did, as any good virologist does, point out the unreliable indirect evidence that they had accumulated to try and claim the existence and presence of a “virus.” Even though they could not see a “virus,” he claimed that filtration procedures had given them some “knowledge” as to the size of the invisible “virus,” stating that it was less than half the size of the “influenza virus.” However, he noted that the size could range anywhere from 20 to 50 mu. Commenting on using the electron microscope to image the “virus,” Dr. Andrewes pointed out that success depended on getting “virus” particles in a state of reasonable abundance and purity, which was not possible at that time. He admitted that the influenza “virus” could not be imaged until they started culturing in embryonic fluids in fertile hens eggs:

“Some knowledge has been gained of the physical properties of the virus. Filtration through graded collodion membranes indicates a particle size rather less than that of influenza virus. This is about 0.1 a or 100 mu across. The experiment shows the difficulty in interpreting results obtained on small groups of subjects. Clearly, the virus has passed the membranes with pores 120 to 140 mu across, but are we to lay stress on the one definite cold produced from a 57 to 68 mu filtrate? If this is genuine the probable size of the virus is around 20 mu or less. If it is a false result, the probable size would be regarded as about 50 mu. The question is of some importance for it would be well worth while attempting with refined optical methods to photograph a virus 50 mu across. One would have much less hope of success with something of half that diameter. I should say something at this point about the prospects of photographing a virus such as this. It is often asked whether the cold virus cannot be depicted by the aid of the electron microscope. Almost certainly it is within the range of sizes accessible to this instrument, but all success in this field depends on first learning how to obtain virus particles in a state of reasonable abundance and purity. That tame, amenable, domestic creature, the influenza virus, was never photographed satisfactorily until we had first learned how to grow it in quantity in embryonic fluids of fertile eggs. So we are back again against the dire need for a way of growing the virus of the common cold."

The CCU researchers were to use these filtered secretions presumed to contain the invisible “virus” in an attempt to “infect” volunteers. If a volunteer experienced symptoms associated with a cold, it would be assumed that a “virus” caused the cold. Ironically, Dr. Andrewes had hoped that his report on their studies “made it clear how much about colds we don't know, and how slow our increase of knowledge is bound to be, unless someone can find a trustworthy method of laboratory study.” While he hoped that the day would come soon, he felt at that time that the problem of studying the common cold was “obscured by the mists of folklore, superstitution and pseudoscience.”

The inability of Dr. Andrewes, and that of his partner Dr. Alick Isaacs, to grow cold “viruses” in the laboratory led them to the realization that they needed to recruit as many human volunteers as they could get if they were going to study a “virus" that they could not find or see. This ultimately led to a marketing push to sell the public on participating in an unusual vacation opportunity in order to acquire the necessary human guinea pigs. The New York Times reported that, at Dr. Andrewes opening press conference, “he made headlines by suggesting that honeymooners might take advantage of the facilities by becoming experimental subjects.” If the crop of human guinea pigs began to thin out, Dr. Andrewes would make a round of appearances on radio and on television to promote the wonderful facility. The main attraction was the price of the stay as it was entirely free, and volunteers would actually earn money for participating. Harvard footed the bill, paying for all travel expenses and supplying $2.80 a day for pocket money. The volunteers would stay in furnished rooms in one of the converted barracks, with each unit of two to three rooms sharing a living room and a kitchen with a refrigerator, a teapot, and a toaster. Warm meals were prepared and delivered to the doors of the volunteers in thermos containers. They had access to a television and a radio-cassette player for music. They had different activities to pass the time such as building jigsaw puzzles, playing board games such as Monopoly or Scrabble, reading books from the library, and using the telephone to make calls. They even had the use of a miniature-golf course, paddle-tennis court or a pool table for recreational activities, as well as the beautiful outdoor countryside of the Salisbury Plains that they could take leisurely strolls outside in nature. All they had to do was stay 10 yards (30 feet) apart at all times, as that was apparently the magic number that the “virus” could not travel beyond.

The facility was advertised in newspapers and magazines as “an unusual holiday opportunity in an attractive part of the countryside, at no cost and with financial reimbursement.” The volunteers were actually encouraged to spread the word amongst friends and family, and they had the option to reapply every six months. In fact, it was considered such a nice stay that one couple alone logged 21 visits at the facility.

As Dr. Andrewes noted, opening an all-expenses paid vacation facility to experiment on human guinea pigs was not the main objective of their work, which was to find a way of studying the common cold without, or with very little, use of human volunteers. The inability to grow the “virus” along with the failures of every effort to produce commercially viable vaccines or antivirals resulted in the facility almost being closed on a number of occasions. The lack of success in their endeavors ultimately led to the appointment of Rockefeller virologist David Tyrrell, who considered himself a “reluctant young virologist,” as the head of the unit to oversee the research in 1957. Tyrell's appointment was seen as a last-ditch effort to culture the “virus” assumed to be responsible for the common cold in order to forestall the closure of the unit. Fortunately for the CCU, this gambit “miraculously” paid off as in 1960, the year that the unit was scheduled for closure, Tyrrell's crew published three papers claiming to “isolate” the common cold “virus.” Thus, the Common Cold Unit survived for another 30 years.

Tyrrell's Tenure

During David Tyrell's tenure, new methods were created to “grow” the “viruses” that they would use to try and “infect” the volunteers with. This involved the researchers experimenting with both tissue and organ cultures in attempts to establish successful “infections.” The first method that they utilized to “grow” a “virus” required human embryo kidney cells that were incubated at 33°C and passaged twice, which resulted in no cytopathogenic effects (CPE), the pattern of cell death claimed by virologists to be a sign that a “virus” is present, resulting in a “successful” culture. The medium was then modified in order to allow for serial passaging and to “speed up” the development of the CPE that the researchers wanted to see, as the original “rhinovirus” cultures took 25 days and at least one passage in order to develop. In other words, they manipulated the cultures until they were able to kill the cell faster and claim success:

“However it is my guess that the development of general methods using tissue cultures, and later organ cultures, of cells, was generally faster and more logical at the Unit where we were able to combine the use of new culture techniques with the inoculation of volunteers to indicate that a cold-producing agent was growing to even a limited extent. We first found a method for propagating many different 'cold' (actually rhino-)-viruses in roller tube cultures of human embryo kidney cells at 33°C for two passages, without a cytopathic effect (CPE) (Tyrrell et al., 1960). The medium was modified, first to allow serial passage and the development of interference, and then to allow a rapid CPE to occur (Tyrrell and Parsons, 1960; Hitchcock and Tyrrell, 1960). Others later found more convenient susceptible cells."

Interestingly, Tyrrell admitted that the human embryo tissues that they utilized were not adequately checked for all possible contaminants. He also stated that they would use monkey kidney cells on occasions and that, as they were unaware of “non-cytopathogenic agents,” the researchers did not look to ensure that these cells were free of all possible contaminants. In other words, the researchers were not using purified preparations that contained only the presumed “viral” particles:

"Extensive use was made of human embryo tissue - this was obtained from patients with no clinical history or evidence of infection and was handled in a 'clean' area. However it was tested only for bacterial and fungal infection before administration to volunteers. Furthermore on some occasions virus propagated in monkey kidney cells was used, and although the cultures were tested for haemadsorbing and cytopathic agents, we did not know

about non-cytopathic organisms such as SV40 and so did not test for them."

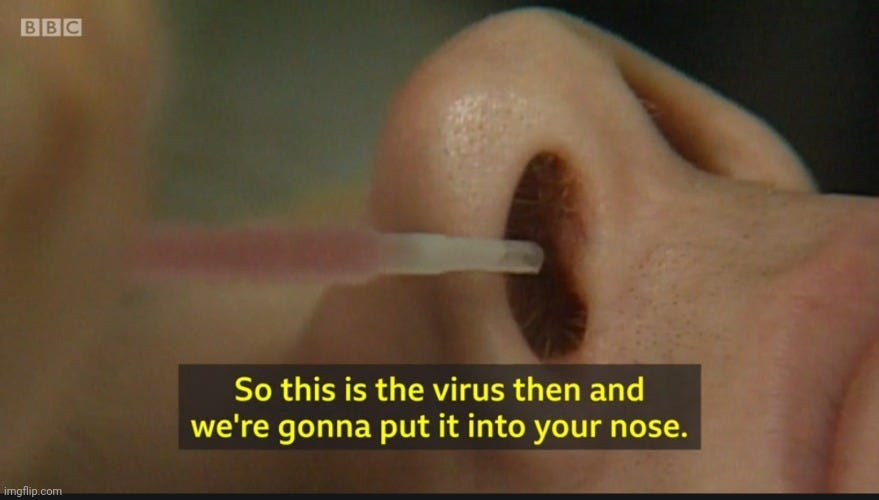

These same organ culture methods were utilized by Tyrrell in 1965 in order to “isolate” the very first “coronavirus” known as B814, which oddly enough, mysteriously disappeared in the early 1970s. In his paper, nasal washings were immediately stored in phosphate-buffered saline and bacteriological nutrient broth. The washings were then transferred into organ cultures of 14-to-22-week-old fetuses mixed with medium 199 and sodium bicarbonate. The medium was changed daily for two days in order to “grow” the “virus.” Interestingly, it was said that the organ culture fluids produced more frequent and severe colds in volunteers than just the unpurified nasal washings alone. Dr. Andrewes had noted in 1950 that the broth and saline that they used as controls never produced colds, but other substances utilized for the same purposes, such as suspensions of normal egg-yolk sac, produced mild colds in small numbers. Thus, the more foreign, unpurified and contaminated the source is, the more cold symptoms that are seemingly produced. Dr. Andrewes also noted how culturing can easily fool the researchers into believing that they have a “virus” when nothing is there, stating “one time we thought we had successfully cultivated cold virus in eggs, but tests with more uninoculated eggs revealed that we had added one more to our unique collection of will-o'-the-wisps.”

Regardless of having more “success” when utilizing cultured soups to inoculate the volunteers with, Tyrrell would later note that the results with culture fluids were regularly unable to be repeated. He spoke of how they needed to manipulate the cultures in order to get the best results, such as using human cells rather than monkey cells, incubating at 33°C instead of 37°C, and using the synthetic medium 199. If they attempted too many passages, the results when trying to “infect” volunteers were always negative:

“We did seem to produce colds with culture fluids but the results would not repeat regularly, and testing the components took ages. There was evidence that the virus would grow, but there were hints that the exact methods we used were important: human cells were better than monkey cells; 33°C was better than 37°C; and synthetic medium 199 was better than the rest. And if we attempted further passes from culture to culture, volunteer tests were negative. The virus died out.”

This is a great example of the illogical leaps that virologists make in order to disregard evidence that contradicted their presuppositions. If a cold failed to arise from the inoculation of cultured fluids, it wasn't due to the fact that there was no pathogenic “virus.” It was that the “virus died out” resulting in the failure of the experiment.

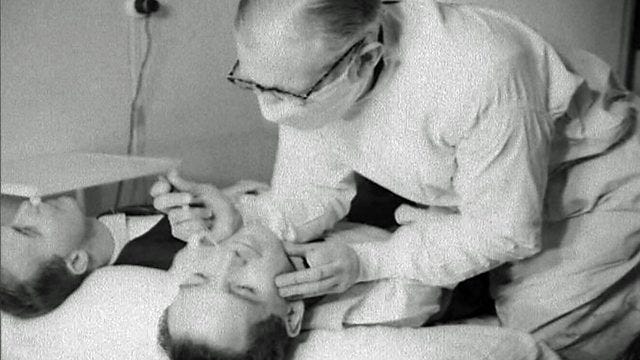

The use of these more toxic cell cultured brews in order to generate the results that the researchers wanted to see was necessitated by the difficulty in establishing and distinguishing colds using only the nasal washings of sick patients. We can see evidence of this difficulty in establishing and distinguishing colds when looking at a 1958 paper from early in Tyrrell's tenure titled Transmission of the Common Cold to Volunteers Under Controlled Conditions. In the paper, it is said that over a 5 year period, the researchers observed more than 1,000 volunteers who were challenged with “infectious” nasal secretions obtained from persons with a common cold or with a blank solution used as a control. The nasal washings were not unadulterated as they were diluted with an isotonic salt solution buffered to pH 7.4 to which 0.5% yeast extract or 5% human Type O hemoglobin was added as a stabilizing protein. However, the researchers attempted to control the variables by also inoculating the control group with solutions containing 0.5% yeast extract or 5% human Type O hemoglobin. The volunteers were intranasally inoculated while in a supine position. Completely objective measures to determine the presence or absence of a cold were not available, so the researchers had to rely on subjective questionnaires filled out by the volunteers where a symptom score of 14 or more was established as the criterion for the presence of an experimental cold. However, this criterion failed to include those who subjectively developed a cold with fewer than 14 symptom points, which was a situation that occurred in nearly one-fourth of the experimental colds. It also included those who were said to develop symptoms from other causes. Thus, the researchers relied on the subjective analysis of a volunteer to determine if they had a cold, even though this was not considered entirely reliable, and included a measure where the presence of increased nasal discharge on three or more of the six days after the experimental challenge was required for those with a score lower than 14. This was meant to exclude those who were “over cooperative” volunteers who diagnosed themselves with a cold on the basis of a “few bizarre symptoms.”

The researchers claimed that the experimental group would produce colds anywhere from 35-40% of the time. However, spontaneous colds also occurred in 10% of the control group. Both “infected” and “noninfected” volunteers would experience the main symptoms associated with the common cold such as headache, sneezing, chilliness, sore throat, malaise, nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, and cough. While it was said that the experimental illness caused more symptoms than the spontaneous colds observed among “noninfected” volunteers, the latter often did not have their full course of symptoms during the period of observation of 6 days. Moderate headache or headache and malaise were experienced by both groups, and it was chalked up to possibly being caused by the experiment rather than any “infection.” Interestingly, experimental “infection” with common cold agents was almost never accompanied by fever, which is supposed to be the hallmark sign of a cold that distinguishes it from allergies. In fact, those said to be “infected” with colds had a significant displacement downwards in temperatures during the first three days after challenge. Thus, one must wonder if all that the researchers produced were simply allergic reactions to foreign proteins. Similar findings were presented by Dr. Andrewes in his 1950 paper, where in the experimental colds produced, “fever is rare. Malaise and headache at onset are common.” Also of note was that the clinicians in this study examining both groups were unsuccessful in using nasopharyngeal signs in order to distinguish volunteers with a cold from those without one. The presence of certain bacterial strains was said to be strikingly similar among the “infected” and “noninfected” groups throughout the subsequent seven days without any increase in their prevalence.

While the researchers believed otherwise, they admitted that, even though they, and several other investigators, had succeeded in producing symptoms referable to the upper respiratory tract by the intranasal instillation of filtered nasal secretions, “the objection might be raised that these symptoms were merely reactions to the foreign material that was introduced.” They also concluded that an experimental cold “cannot be readily detected by examination of the nose and throat even by a person well qualified in otolaryngology” as there is “great variation in the appearance of the nasopharyngeal mucosa among average well persons.” Interestingly, in a seeming attempt to bolster their own results, the researchers cited various studies, along with their own unpublished data, stating that the nasal instillation of live “adenovirus” from a tissue culture harvest, live egg-passaged influenza “virus,” bacteriophage, “noninfectious” nasal secretions, and several foreign chemicals did not cause symptoms after instillation into the nose, thus discrediting the supposed “infectiousness” of both “adenovirus” and “influenza” in the process. Despite the fact that within their study the control volunteers, who were given solutions said not to contain any “virus,” also developed cold symptoms, the researchers ultimately concluded that the study was a success in showing that a “virus” can be transmitted by the nasal instillation of dilute, cell-free, nasal secretion from donors with a common cold.

Failure to Launch

The difficulty that the researchers under Tyrrell had in producing and/or distinguishing experimental colds was not much better during the early days of the CCU under Dr. Andrewes either. For example, Dr. Andrewes recounted in 1949 that, in an experiment using nasal washings from healthy patients that were tested on 28 other patients, 6 colds were produced. He admitted that there was no evidence that any “virus” was the cause of the colds. Thus, using nasal washings from healthy hosts with no “viruses” can result in the exact same symptoms seen in experimental groups using fluids presumed to contain a “virus.”

In Dr. Andrewes’ 1962 Harben Lecture, he recalled how they exposed normal volunteers to “infected” subjects who were at various stages of illness. However, he noted that: “To our surprise, very little cross-infection occurred.” In fact, in the example provided, 19 people were "exposed” to those with colds for 10 hours, and only one person was said to be “cross-infected.” The cold was claimed to be given to him by an “infected” person who had no symptoms of disease, i.e the asymptomatic excuse. Regardless, Dr. Andrewes noted that their findings lined up with those of Kerr and Lagen (1933-34) who also failed to obtain evidence of natural transmission of colds. Later attempts by the CCU were considered failures as well, as a second (0 out of 4) and third (1 out of 5) test with inoculated materials did not produce the expected results, as was the case with a “natural wild cold” which failed to pass on to any of the 5 healthy people exposed. As such, other avenues were searched for to try and demonstrate “cross-infections.”

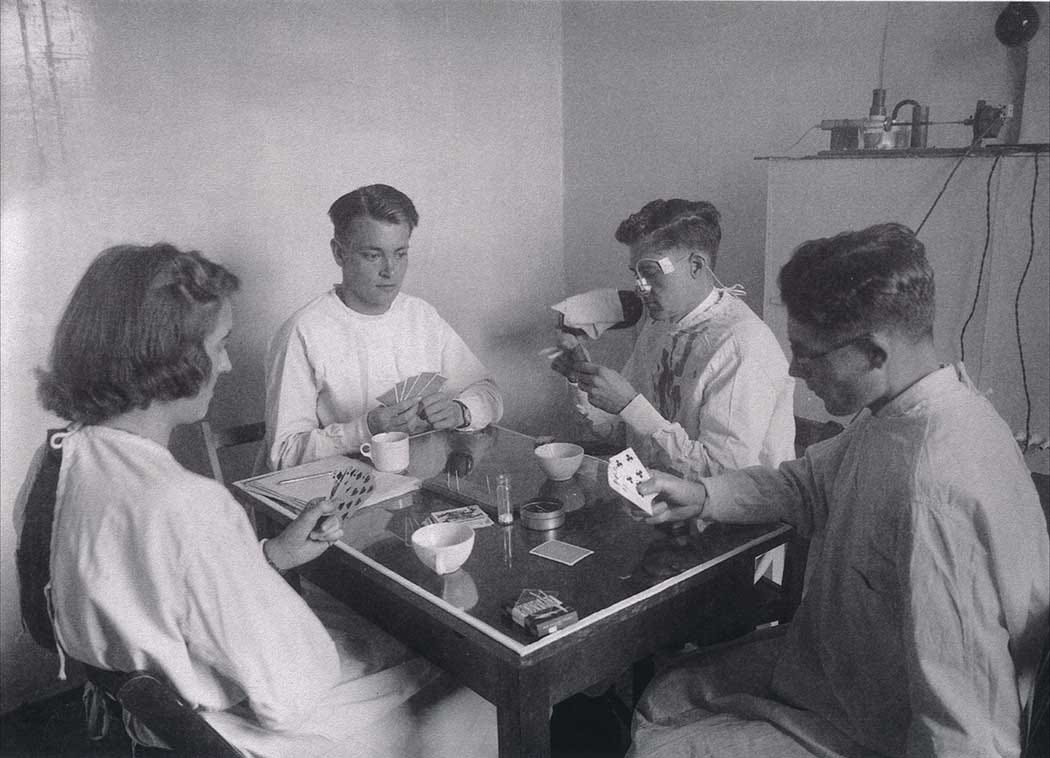

A later experiment led Dr. Andrewes to isolate a group of twelve volunteers all summer long on the uninhabited island Eilean nan Ron off the northern coast of Scotland. In mid-September, he sent a boat of “infected” volunteers to the island to interact with the previously isolated island group. According to Dr. Andrewes, the “infected” were “liberal in the way they disseminated nasal discharge on playing cards, books, cutlery, handles of cups, letters, chairs, door-handles, and tables” and they regularly coughed at the island group for hours from behind a blanket partition. Various methods were used in attempts to “infect” the islanders, and testing showed that fine droplets from the “infected” had travelled throughout the room. The “infected” even lived in a separate house for three days with some of the islanders, offering maximum exposure. However, none of the island group caught so much as a sniffle, even though considerable efforts were made to “infect” them. Dr. Andrewes recounted, “Much to our surprise no colds had developed in any of the 12 exposed ‘islanders’ by Sept. 29. It was particularly unexpected that none of party C caught colds, though very fully exposed.” Dr. Andrewes got anxious and then sent a man who was said to have a “wild” cold to sit and interact with the island group for a while. Even though it was then claimed that three of eight eventually caught his “wild” cold, later demonstrations to “infect” the healthy through the air were considered unsuccessful.

The New York Times article pointed out other attempts where Dr. Andrewes would send volunteers off for long walks on cold days, turn off the heat in their flats, and even made them sit around in wet socks without any success in producing colds. He reflected, “We couldn't satisfy ourselves that chilling by itself did anything.” In the article “The Sneeze Hunt” published in Leader magazine in April 1950, a quote from a volunteer was provided highlighting the lack of success:

"The eighth day – and all I can boast is a slight snuffle…something really must be done…The mist is heavy early next morning as, scantily-clad, I go down to the river…I plunge up to my knees in icy water, old shoes, socks, slacks and all…an hour later [I change] into dry clothes…We wait all day. Nothing happens…The irony of it.”

Similar attempts to either induce or suppress the expression of cold symptoms in volunteers were made under Tyrrell's tenure as well, and these efforts were largely unsuccessful. This led Tyrrell to suggest that “perhaps we should leave the attack on the virus to the human immune system.”

According to David Tyrrell's obituary write-up for Dr. Andrewes, when John Enders introduced his roller tube cultures of human embryo cells to propagate “poliovirus,” these same techniques were implemented at the CCU under Dr. Andrewes watch. The researchers there acquired the nasal washings from a scientist who was doing much of the culture work for the CCU, and then inoculated the sample into plasma clot cultures of human embryo lung cells. Even though no cytopathogenic changes were observed, they serially passaged the culture and then inoculated volunteers who subsequently developed colds. The researchers assumed that a “virus” must have reproduced, and they reported the results in a paper published in the Lancet in 1953. After publication, however, Dr. Andrewes stated that “we could no longer repeat our own results,” thus showing that the published results were erroneous and that the experiment was entirely unsuccessful.

Cold-Free Holiday

Regardless of whether the researchers attempted to “infect” the volunteers through the use of the unpurified nasal washings of those suffering common cold symptoms or with the toxic cell cultured creations devised under Tyrrell's watch, a main theme emerged amongst the populace concerning whether to take a chance on the common cold vacation. As noted by Professor Nigel Dimmock, who worked at the Common Cold Unit in the 1960s, “it was a good deal because the chances of getting a cold were pretty slim." The New York Times profile stated that most volunteers were relatively unruffled about the risks due to the fact that it was extremely hard, to the volunteers' delight and the staff's frustration, to “infect” another person with a cold even under the idealized conditions. According to Dr. Robert Philpotts, a staff virologist, “one of our biggest problems is giving people colds.” He felt that if he could give 80 percent of the people colds, that they could have finished their work very quickly. However, the actual estimates varied between one in three (33%) and one in five (15%). Few of the volunteers caught colds, and they actually had largely pleasurable stays at the facility, with many people returning for multiple stays. There were several romances that blossomed, such as one that developed between a male guitarist and a female oboist who dueted together outside of their units. Reviews were almost entirely positive throughout its 4+ decade history. A male teacher, who was an early volunteer of the facility, recalled his two peaceful experiences there with neither visit producing a cold:

“It was a fine place. I was able to retreat in the monastic sense, once to read, the second time to revise for an impending examination. Everything was gently controlled and, although the Scottish matron was somewhat unnerving and terrifying, the lack of authority, apart from the very few things we were forbidden, was a good relaxation after a heavy term of teaching. And I was given a cold on neither visit.”

Another teacher, a female who volunteered six times in eleven years, also had fond memories:

“Time flew, sewing, reading, going on the occasional walk. It was a complete break from the world, a time to return to the freedom of childhood without its restraints. The yellow trolley (bringing meals) was a highlight of the trials. Pavlov’s dogs had nothing on us.”

Ironically, Dr. Andrewes eldest son John was also a volunteer at the facility three times and stated: “Nobody succeeded in giving me a cold.”

Even though it was admittedly very difficult to produce colds experimentally, Tyrrell noted that “many of the volunteers were quite eager to catch a cold, even to the point of imagining the symptoms.” Evidence of this was seen in the 1958 study mentioned previously with the “over cooperative” subjects. Interestingly, it has been known since at least 1930 that volunteers could convince themselves that they had a cold if they believed that they were being “infected” with a cold producing agent. This was demonstrated by Alphonse Raymond Dochez in his paper Studies in the Common Cold. Oddly enough, this was the paper that convinced Dr. Andrewes that the common cold was due to a transmissable “virus” to the point where he adopted the views of Dr. Dochez as the CCU's working hypothesis. In the 1930 paper, Dr. Dochez not only noted that volunteers could convince themselves that they had a cold when they did not, he also stated that the filtrates, regardless of whether containing the assumed “virus” or not, caused stuffiness, sneezing, and headaches:

“It is very easy for an individual who is being used for a transmission experiment to believe that he has a mild cold although objective evidence is extremely slight or absent. Where, as in the beginning of our work, volunteers believed that we were trying to produce colds, they were self-convinced occasionally that they were suffering from a mild infection. This was much easier of belief as the filtrate in practically all the cases, negative and positive, causes some slight stuffiness of the nose, a little sneezing and occasionally slight headache.”

As an example, Dr. Dochez spoke about a patient who was given an injection of sterile broth without “virus.” When he was accidentally told by an assistant that he had failed to catch a cold, that night, the man began to suffer severe symptoms. When he was told the next morning that he had been misinformed about the nature of his injection, the man’s symptoms disappeared within an hour:

“It was apparent very early that this individual was more or less unreliable and from the start it was possible to keep him in the dark regarding our procedure. He had inconspicuous symptoms after his test injection of sterile broth and no more striking results from the cold filtrate, until an assistant, on the second day after injection, inadvertently referred to his failure to contract a cold. That evening and night the subject reported severe symptomatology, including sneezing, cough, sore throat and stuffiness of the nose. The next morning he was told that he had been misinformed in regard to the nature of the filtrate and his symptoms subsided within the hour. It is important to note that there was an entire absence of objective pathological changes.”

The power of the nocebo effect, which is where the belief that a negative outcome from a treatment or procedure actually causes the manifestation of that outcome and results in harm, is a well-known phenomenon. This was something acknowledged by researchers before, during, and after the CCU experiments. In the CCU's intake form, they advised that “the volunteer should not be bound to think that he will develop symptoms after being given nose drops.” In fact, they admitted that “there is a good chance that he may not” as “some volunteers prove resistant to the virus inoculum anyway.” They admitted that “by and large, only about one third of all volunteers actually develop symptoms.” These symptoms are non-specific, and they are exactly the same as those attributed to hay fever and seasonal allergies. Thus, on top of the issues with patients manifestimg symptoms due to the belief that they may get a cold just from undergoing the experiment, the interpretation of a cold is entirely subjective which is why they utilized a double-blind set-up to try and mitigate “incorrect interpretations” by the researchers as well as to ensure that they did not imagine signs and symptoms that were not there. Just the action of injecting these solutions into the nasal cavities, regardless of whether they contain a “virus” or not, will result in symptoms such as headache, malaise, stuffiness, and sneezing, as noted by Dr. Dochez and the authors of the 1958 study. Thus, it can be easily concluded that it is due to the experimental procedure itself, along with the reaction, both physically and mentally, of the individual to the presence of foreign substances, that results in the occurrence of the non-specific symptoms which are then subjectively interpreted to be the common cold by the researchers based upon the inoculum given.

In order to actually conclude that they were successful in producing and studying cold “viruses,” the researchers at the CCU had to go to great lengths to disregard evidence that showed otherwise:

The inability to make numerous animals sick with the same disease.

The inability to produce “coinfections.”

The inability to transmit “infections” through the air, even in heavily contaminated environments.

The ability of the experimental procedure of intranasal inoculation itself producing fatigue, malaise, sneezing, and a stuffy nose.

The great difficulty (15-33% “success” rate) to produce cold symptoms using “virus” samples as well as being unable to replicate the results consistently.

The inability to come up with successful treatments and vaccines.

The nocebo effect producing the same symptoms associated with the common cold.

The control groups also coming down with the same symptoms of disease associated with the common cold despite being given solutions said not to contain any “virus.”

While the textbooks may claim that the Common Cold Unit was successful in identifying common cold “viruses” along with transmitting and studying the disease, it is very clear looking at its history that it was anything but a success. For a facility that wanted to study the common cold “virus” by “infecting” their human guinea pigs, they had an awfully difficult time doing so resulting in an admittedly low “success” rate. The little “success” that they did have could easily be explained away by different confounding factors that were unrelated to the presence of any “virus.” After various threats of closing the facility over its four decades in operation, the last trial was concluded in July of 1989, and the facility was finally closed for good in 1990. The Medical Research Council ultimately decided not to continue the work conducted at the facility anywhere else. Thus, the question must be asked: can a facility be considered successful in producing valuable research and evidence when it was closed down for “financial reasons” with its research halted completely? Closures do not happen if something is viewed as successful and worthy of investment. Giving out free all expenses paid vacations while paying staff and volunteers for their efforts with little results to show for it doesn't seem like a sound financial investment. Perhaps some interesting advice given to David Tyrrell by Dr. Andrewes was overheard by those with the pocket books who were looking for a return on their investments, and it made them realize that it was not meant to be:

“You shouldn’t be interested in why volunteers given viruses get colds, but why so many don’t!”

As well as an interview with Dr. Ann McCloskey who has courageously fought against the draconian “COVID-19” measures and vaccines since 2020.

interviewed Dr. Mark Bailey over the Baileys new book “The Final Pandemic.” took a look at what goes into the manufacturing of the synthetic vitamins that are added to our food supply. has three offerings this week, with the first detailing Israel's Ministry of Health admitting to no scientific evidence for “SARS-COV-2” as well as for a valid test.The second discussed Dr. Peter McCullough odd “viral obelisks” evidence.

The third deals with the CDC’s admittance of having no scientific evidence for either cowpox or Alaskapox.

wrote many excellent pieces explaining why it is so important to expose germ “theory"and virology at this very time.

Another piece of great research, Mike! You are so thorough. And thanks a bunch for linking my articles!

Reading your opening paragraph I thought you were finally going to mention a context for getting ill as an 'escape' strategy operating at deeper levels of consciousness than our so called 'consciousness'.

There is a principle of diversionary defence by which to offset or escape a greater fear with a lesser evil - especially where the lesser evil can attract sympathy in place of an acute conflict.

This perspective will always trigger outrage as if it operates a blaming for being sick on top of suffering - which properly understood it does not. It also casts expert doctors as being used or fooled by their proclivity to believe their diagnostic prowess.

Overwhelming mental or emotional conflict can trigger a masking dissociation to a displacement or diversionary escape in which the conflicts are acted out on the body or indeed the bodies of others. Its a scapegoat mechanism for buying time against exposure such as to be 'saved' on one level by the sacrifice of another.

Szasz wrote on this as a much broader use of the term malingering than skiving.

In A Course in Miracles is stated "Sickness is a defence against the truth" - but without some recognition of the terror that underlies fear of total exposure to truth the phrase will be misunderstood. The body can be transparent to Communication (life) & thus serving true function, or it can be used as if an end in itself which will conflict with and block function - ie dissonance cast out in guilt for loss of connection (love).

This is all very 'deep' but as it came up, I felt to offer it.