One of the reasons I like to engage with people who challenge me about pathogenic “viruses” and bacteria is that I always come away with something new from these discussions. I find that I often uncover evidence that I had not previously come across before while searching to find relevant information to either explain my position better or to refute a claim that is made. Upon doing so, I am able to further reinforce my position and gain an even deeper understanding than I had held previously. Even though some of these conversations can be a headache, building up my evidence base to present a stronger position makes these encounters ultimately worthwhile.

For example, a user on Twitter recently tried to claim that Robert Koch was able to prove that the tuberculosis bacterium was pathogenic in humans. This person made the argument that the fact that Koch was awarded with the Nobel Prize in 1905 was sufficient evidence proving that Koch had shown Mycobacterium tuberculosis was pathogenic in humans. The other reason given was that it was widely accepted as a fact by historians that Koch had provided said proof.

To anyone looking at this logically, a majority agreeing on a statement does not necessarily make said statement true no matter how much it is repeated. In fact, this is a logical fallacy known as appealing to the common belief:

Thus, the argument that the majority believed the claims about Koch to be true so it must be true was entirely irrelevant to me. However, the Nobel Prize was an interesting angle which I decided to entertain and explore. I already knew from previous research that the Nobel Prize is a worthless measure as people highly worthy of recognition are regularly passed over for those who do not deserve such accolades. Also, receiving the award does not necessarily mean that the discovery it was granted for was indeed correct. We need to look no further to confirm this fact than to examine the case of Wendell Meredith Stanley, said to be the first virologist to achieve getting the tobacco mosaic “virus” in pure crystal form in 1935. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1946. According to his Nobel Prize page, the prize motivation was for the “preparation of enzymes and virus proteins in a pure form.”

Many infectious diseases are caused by viruses—very small biological particles. They are far too small to be visible under a microscope and could only be identified with the help of the symptoms they cause. Wendell Stanley studied the tobacco mosaic virus, which attacks the leaves of tobacco plants. From considerable quantities of infected tobacco leaves, he succeeded in extracting the virus in the form of pure crystals in 1935. Through further research, Stanley was able to show that the tobacco mosaic virus is composed of protein and ribonucleic acid, or RNA.

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1946/stanley/facts/

However, did Stanley really achieve pure crystal forms of TMV? Were his Nobel Prize winning conclusions correct or was he awarded due to his connection to the Rockefeller Institute and his association with powerful players who wanted his evidence to succeed? We can see from his Wikipedia page that Stanley’s research turned out to be incorrect:

“Stanley was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1946. His other notable awards included the Rosenburger Medal, Alder Prize, Scott Award, the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement[3] and the AMA Scientific Achievement Award. He was also awarded honorary degrees by many universities both American and foreign, including Harvard, Yale, Princeton and the University of Paris. Most of the conclusions Stanley had presented in his Nobel-winning research were soon shown to be incorrect (in particular, that the crystals of mosaic virus he had isolated were pure protein, and assembled by autocatalysis).[4][5]”

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wendell_Meredith_Stanley

While I dislike relying on Wikipedia, I have no issues using it when the information is well sourced. We can get further confirmation of the Wikipedia conclusion by looking at the two sources provided. Unfortunately, I was unable to access this first paper in full but we get just enough from the abstract to see that Stanley’s Nobel Prize-winning conclusions were ambiguous, i.e. the quality of being open to more than one interpretation; inexactness:

The discovery of the chemical nature of tobacco mosaic virus

“The world of Virology continues to consider Stanley as the first scientist who elucidated the actual nature of a virus, and this eminent scientist was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, in 1946. By examining the papers Stanley published from 1937 to 1945, one can however find proof of his ambiguity, a fact that justifies the bitterness of Bawden and the sarcastic comments of Pirie.”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11048483/

The second paper cited by Wikipedia paints a much clearer picture. Stanley's work was considered flawed and full of technical errors. His “pure” crystal of TMV turned out to be not so pure as it contained water and other impurities including a significant fraction of nonprotein. Stanley made claims without adequate evidence and he benefitted greatly from social acquaintances which helped him to be awarded with the Nobel Prize. Eventually, his errors were said to be corrected and his old theories were discarded, leaving his results to be reinterpreted in order to be incorporated into the “successful” investigations category:

W. M. Stanley's Crystallization of the Tobacco Mosaic Virus 1930-1940

“Yet Stanley's work was flawed by technical errors and misconceptions. As several critics in the late 1930s pointed out, without receiving much attention, his virus sample contained water and impurities and thus was not a true crystal. It also contained a significant fraction of nonprotein material-about 6 percent nucleic acid (RNA)-which Stanley had missed entirely, and which turned out to be the crucial component, the viral hereditary material. Furthermore, the property of self-replication in viruses was not based on enzyme action and crystal growth, as Stanley often claimed without adequate evidence, but turned out to be a direct consequence of the structure of nucleic acids. How can we explain these technical and conceptual errors in the light of the international recognition bestowed on the young Stanley and his leadership in science?”

“Stanley also drew heavily on the protein researches and on the scientific reputation of The Svedberg and Arne Tiselius at the University of Uppsala. The Uppsala group had a special relationship with the Rockefeller Institute and shared its sophisticated Swedish technology and its laboratory expertise, as well as some scientific biases, with members of the institute. In cultivating the Uppsala connection, Stanley benefited from technological and social advantages that placed his laboratory in the vanguard of research. Tiselius's support and influence carried considerable weight with the Nobel Committee in awarding Stanley the chemistry prize (Tiselius himself was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1948).3”

“Physicochemical techniques alone did not uncover the key to biological knowledge. Eventually Stanley's errors were corrected, his results reinterpreted, and old theories discarded, reintegrating Stanley into an account of biology that is "restricted to the enumeration of successful investigations."

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3533840/

The case with Stanley and the awarding of a Nobel Prize for work which later turned out to be erroneous and inaccurate is not the only time that this type of situation has occurred. There are, in fact, numerous instances out there for anyone willing to look. However, I want to highlight one more as it relates to another assumed pathogenic entity, Spiroptera carcinoma. In 1926, Johannes Fibiger won the Nobel Prize for his “discovery” of what he thought was a parasitic worm which caused cancer. However, research over the decades proved that the worm definitely had no pathogenic or cancer-causing capabilities. Later research showed that the tumors Fibiger thought he had witnessed in experimental mice were instead just lesions in the stomachs of the mice due to a nutrient deficiency from a poor diet. The article below points out that Fibiger fell victim to improper controls and inadequate technology which led to his erroneous observations and conclusions. His story serves as a reminder of the faulty methods and reasoning that is sadly pervasive in the sciences today:

Disproved Discoveries That Won Nobel Prizes

“Over a million papers are published in scientific journals each year, and as Stanford University professor John Ioannidis wrote in a now legendary paper published to PLoS Medicine in 2005, most of their findings are false. Whether due to researcher error, insufficient data, poor methods, or the numerous biases present in people and pervasive in the ways research is conducted, a lot of scientific claims end up being incorrect.

So it should come as little surprise that Nobel Prize-winning discoveries are not immune to being wrong. Though marbleized in prestige, a number of them have been either disproved or lionized under mistaken pretenses.

PERHAPS THE MOST clear-cut example hearkens all the way back to 1926, when Johannes Fibiger won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for "for his discovery of the Spiroptera carcinoma." In layman's terms, he found a tiny parasitic worm that causes cancer. Subsequent research conducted in the decades following his receipt of the award would show that though the worm definitely existed, its cancer-causing abilities were entirely nonexistent. So where did Fibiger go wrong?

Though widely respected and considered to be a careful and cautious researcher, Fibiger fell victim to improper controls and inadequate technology. To elucidate his hypothesized connection between parasites and gastric cancer in rodents, he fed mice and rats cockroaches infested with parasitic worms and observed what he thought were tumors grow inside the rodents' stomachs. Later studies would show that they were not tumors but lesions likely caused by vitamin A deficiency, which resulted from a poor diet.”

“Analyzing Fibiger's story in a 1992 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine, Tamar Lasky and Paul D. Stolley were kind in their remembrance:

"We now know that gastric cancer is not caused by Spiroptera carcinoma, and the purported "discovery" of such a relation hardly seems worth a historical footnote, never mind a Nobel Prize. At the same time, it is quite touching to read the speech given by the Nobel Committee on presenting Fibiger with his award. They considered his work to be a beacon of light in the effort of science to seek the truth. Perhaps his work did serve to inspire other scientists to conduct more research and to persist along the path of human knowledge...

...Fibiger's story is worth recounting not only because it teaches us about pitfalls in scientific research and reasoning, but also because it may provide perverse solace for those of us who will never receive the Nobel Prize (but, of course, deserve it)."

https://www.realclearscience.com/blog/2015/10/nobel_prizes_awarded_for_disproved_discoveries.html

Clearly, just being awarded a Nobel Prize is not conclusive proof that the work it was given for was in fact accurate. However, I decided to entertain this person's logically fallacious reasoning due to my morbid curiosity as to what I may find out upon further investigation. Presented below are some very interesting highlights from the Nobel Prize presentation speech by Professor the Count K.A.H. Mörner, Rector of the Royal Caroline Institute, on December 10, 1905. I have also provided excerpts from Robert Koch's own 1905 Nobel Prize speech as well as a rather revealing admission made in the reprinting of Koch's 1882 tuberculosis paper. This should put to bed any claims that a Nobel Prize is evidence that Koch proved the Mycobacterium tuberculosis was pathogenic in humans.

To begin with, there are some rather interesting revelations made during Robert Koch's award ceremony presentation speech by Count K.A.H. Mörner which highlight the inconclusive findings associating bacteria as a cause of disease. For instance, in this speech, it was revealed that:

The causal relationship between bacteria and diseases was obscure.

There were grounds for supposing that certain other diseases were caused by micro-organisms, yet detailed knowledge concerning this was lacking, and experimental findings were very divergent.

The question still remained open as to whether bacteria observed in a disease were also its cause, or whether their development should rather be considered a result of the pathological process.

Investigators had to look in vain for bacteria in the organism while only some found them.

Bacteria were often of a different appearance which gave reason for doubting that they were the specific and genuine cause of the disease.

The same bacteria was found in widely differing types of disease.

Evidence either showed that the same disease could be caused by different bacteria or the same bacteria could produce different diseases.

Experiments which were carried out often could not demonstrate whether a real bacterial invasion of the organism had taken place.

According to Mörner's speech, Koch required that the bacteria must always be demonstrable in a particular disease and should develop in a way that would account for the pathological process. Koch laid down the expectation that there must be specific properties distinguishing individual bacteria. Even if they resemble other bacteria in their form, etc., the bacteria must be different from one another by their biological property. This meant that every disease must have its own special bacterium even if the bacteria appeared to be identical.

Before Koch began his work with the tuberculosis bacterium, it was possible to poison and create experimental tuberculosis by inoculations into animals. However, it was not proven that it was caused by a bacterium. This interpretation of a micro-organism as a cause was contested by very distinguished investigators. When Koch initially presented his findings on tuberculosis in 1882, he provided his evidence on the discovery of the tubercle bacillus and the description of its chief characteristics. Koch eventually used his findings in an attempt to create a “cure” known as tuberculin in the 1890's, but this “cure” did not live up to expectations and was quite the ineffective embarrassment for Koch.

These are but a few of the interesting highlights. The entirety of the speech is presented below:

Award ceremony speech

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen.

The Staff of the Royal Caroline Institute takes great pleasure in giving this year’s Nobel Prize for Medicine to the man who takes precedence among those now alive as a pioneer in bacteriological research, the prize being awarded to Geheimrat Robert Koch for his work and discoveries concerning tuberculosis.

This work comprises only part of his activities, through which he has rendered such great, indeed unique, services to medical progress during the last decades. Even if it is only the part mentioned which is the object of this year’s award, I must still briefly enumerate the main features of his activities as a whole. The meaning of his work on tuberculosis is brought out more vividly and powerfully if this is seen in the context from which it took its origin.

To make Koch’s significance in the development of bacteriology clear, one must take a look at the situation with which Koch was confronted when he made his appearance. Pasteur had indeed already published by then his epoch-making work, which laid the foundations of bacteriology, and medical art had already gathered in one very beneficial fruit which stemmed from this work, namely the antiseptic method of treating wounds proposed by Lister. However, the trail was yet to be blazed, which bacteriological research has followed with such success during recent decades, to discover the causes of individual diseases and to look for the means of combating them. Koch was a pioneer in this.

For two diseases namely anthrax and typhus recurrens in which micro-organisms of a particularly characteristic appearance were relatively easy to demonstrate, it was agreed that the latter were the causes of these diseases. Otherwise the causal relationship between bacteria and diseases was obscure. It is true that there were good grounds for supposing that certain other diseases were caused by micro-organisms. But detailed knowledge concerning this was lacking, and experimental findings were very divergent. So, for instance, it was not established whether normal healthy organs contained bacterial germs. This was certainly contested by various prominent investigators, but on the other hand this view was defended by other also prominent authors. Then the question still remained open of whether bacteria observed in a disease were also its cause, or whether their development should rather be considered a result of the pathological process. In addition, in studying one and the same type of disease various investigators looked in vain for bacteria in the organism, while others, however, found them. Moreover, bacteria, which various investigators had observed in a particular disease, were often of a different appearance, so that there was reason for doubting that they were the specific and genuine cause of the disease. On the other hand, in widely differing types of disease, bacteria were met with which, as far as was known, were of one and the same kind, and this gave still more cause for adopting a position of doubt with regard to the causal relationship between these bacteria and the pathological process. It was indeed difficult to imagine that the bacteria discovered had to be regarded as the essential causes of disease, since it looked partly as if the same disease could be caused by different bacteria, and partly as if the same bacteria could produce different diseases. It was easier to suppose that the bacteria all had the property of facilitating the development of the disease by exercising an influence on the organism. The uncertainty was that much greater since the experiments which were carried out often could not demonstrate whether a real bacterial invasion of the organism had taken place.

In 1876 Koch entered the field of bacteriological research with an investigation of anthrax, and two years later he produced his classical investigations into diseases from wound infections. With the views set out there and the way he formulated the questions, he had a fundamental effect on the further development of bacteriology, and the ideas he expressed there recur as a leading motive in his subsequent research and form the foundation of modern bacteriology, as they do of the axioms of hygiene which are derived from it.

He stressed that, if bacteria caused a disease, then they must always be demonstrable in it, and they should develop in a way such that this would account for the pathological process.

He further stressed that the capacity to produce disease could not be a general property of bacteria or one common to them all. On the contrary it should be expected in this respect to find specific properties distinguishing individual bacteria. Even if they resemble other bacteria in their form, etc. they must still be different from one another by virtue of this biological property: in other words, every disease must have its special bacterium, and to combat the disease, it would be necessary to look for clues in the biology of the bacterium. Koch therefore not only set himself the task of examining the problem of whether diseases were caused by bacteria, but also endeavoured to discover the special micro-organisms of the particular diseases and to get to know more about them: this was a problem which, in the circumstances then prevailing, seemed to offer very little hope of being solved. In the way Koch solved this problem he was just as much, if not more, of a pioneer, then he already was in the abovementioned precision which he had given to the formulation of the problem.

To start with, developing a general methodology is as valuable as finding the correct technique for every special case. Koch’s genius has blazed new trails in this respect and has given present-day research its form. To give a detailed description of this is beyond the scope of this account. I only want to mention that he had moreover already given a significant development to techniques in staining and microscopic investigation as well as in the field of experiment in his earliest work. Shortly after this he produced the important method, which is still generally the usual one, of spreading the material under investigation in a solid nutrient medium to allow each individual among the micro-organisms present to develop into a fixed colony, from which it is possible, in further research, to go on to obtain what is known as a pure culture.

Shortly after the publication of his investigations into diseases from wound infections Koch was appointed to the new Institution, the «Gesundheitsamt» (Department of Health), in Berlin. There he started work on some of the most important human diseases, namely, tuberculosis, diphtheria and typhus. He worked on the former one himself. The two latter investigations he left to his first two pupils and assistants, Loeffler and Gaffky. For all three diseases the specific bacteria were discovered and studied in detail.

To give an account of the work which Koch carried out, or accomplished through his pupils, and also to mention the work which derives more indirectly from Koch, would nearly be the same as describing the development of bacteriology over the last few decades. I will content myself with naming some of the most important discoveries and items of research which, in addition to those already named, are more directly linked with Koch’s name. At the head of the German Cholera Commission Koch investigated the parasitic aetiology of cholera in Egypt and India, and discovered the cholera bacillus and the conditions necessary for its life. Experience thus gained found practical application in the development of measures taken to prevent and combat this devastating disease. In addition Koch made important investigations concerning plague in humans, malaria, tropical dysentery, and the Egyptian eye disease (trachoma) among others, and now finally concerning typhus recurrens in tropical Africa. He has also carried out work of exceptional importance, concerning a host of destructive tropical cattle diseases, such as rinderpest, Surra disease, Texas fever, and finally concerning coast fever in cattle and the trypanosome disease carried by the tsetse fly.

Through the perfection he gave to methods of culturing and identifying micro-organisms, he has been able to carry out his work with regard to disinfectants and methods of disinfection so important for practical hygiene, and advice concerning the early detection and combating of certain epidemic diseases such as cholera, typhus and malaria.

Now I move over to a brief account of the series of investigations which is the object of the present award.

The idea that tuberculosis is infectious goes back a long way to Morgagni. Already before Koch had started his investigations into this disease, it had been possible to show that tuberculosis may be inoculated into animals. It was not, however, proved that it was caused by a micro-organism, and such an interpretation was contested by very distinguished investigators.

Koch made his first communication concerning his research on tuberculosis in a lecture given on March 24, 1882 to the Physiological Society of Berlin. This lecture covers scarcely two pages of print, yet in it are given the proofs of the discovery of the tubercle bacillus and the description of its chief characteristics. The method for staining it in the affected tissue is described there, its constant occurrence in tuberculous processes in man and beast is mentioned, the procedure for producing pure cultures of it is described, and information is given concerning typical and positive results of inoculating the bacillus in animals. It was emphasized there, in addition, that the bacillus is dependent on the living organism for its development and multiplication, and that hence tuberculous infection is derived primarily from the expectorations of consumptives, and that it can probably also be caused by cattle suffering from «pearl disease».

By this epoch-making discovery, which immediately established the characteristic features of the bacteriology of tuberculosis, a broad field for further research into this disease was disclosed. Until recently Koch has continued his investigations into this disease with his invincible enthusiasm for research, and has endeavoured to solve the difficult questions which have presented themselves. During the 1880’s he was, however, hindered in this for a long time by public duties. His next striking piece of work appeared in 1890, when he published his investigations into the effect which certain materials, so-called tuberculin, formed in cultures of tubercle bacillus, have on the organism. They provoke, that is, a strong reaction, which it was also intended to use for therapeutic purposes. It is true that, as a cure for tuberculosis, it did not live up to what was hoped of it, which had been exaggerated out of proportion by the strong desire of the public and probably also of doctors for a cure of this disease. Despite all that, it has attracted attention again of late, and, in the form in which it is now obtained, it is thought that it can be used advantageously in the curative treatment of tuberculosis; and for this purpose it has had an application, albeit a limited one. It has continued to retain great importance as a means of diagnosing tuberculosis in the early stages or in a concealed form, and for this purpose it has an extensive application in the struggle against tuberculosis in cattle. This work has also been of great significance as a precursor to serum therapy, which has been so successful in other fields.

Recently, in 1901 to be exact, Koch has added another sensational link to the chain of his research on tuberculosis, when he presented his findings concerning the relation between human and bovine tuberculosis to the Congress on Tuberculosis in London. He found that human tuberculosis could not, as a rule, be inoculated into cattle, while they were very susceptible to bovine tuberculosis. So he found a very noteworthy difference between the tubercle bacilli of the two diseases. Experience at that time, concerning the transmission of tuberculosis from cattle to humans, gave Koch cause to consider bovine tuberculosis as being of only quite secondary importance in the development of human tuberculosis, whereas in this respect he strongly emphasized and stressed the spread of tuberculosis between humans.

Koch’s view that a definite difference existed between the tuberculoses from the two sources named, and his opinion that bovine tuberculosis was relatively harmless, met with strong opposition, whereby a diametrically opposed viewpoint was also strongly affirmed. Accordingly Koch’s pronouncement caused a long series of investigations. His observation on the low virulence of human tuberculosis in cattle can now be considered established. It has also been found that the difference goes further, when it was found that there are certain typical dissimilarities with respect to the way they grow, etc. between tubercle bacilli from these two sources. In this way it was possible to approach, even if not to give conclusively, the answer to the difficult question of the possibility or frequence of transmission of bovine tuberculosis to humans. The current position regarding this question permits it to be answered for the present to the extent that tubercle bacilli of the same sort as those in cattle have indeed been found in humans, and seen to be present more often than experience in 1901 gave reason to believe, and on this account the matter must be given continued attention; however, the number of cases in which such bacilli have been met with, together with other observations, especially the frequency of human tuberculosis in districts where bovine tuberculosis is either lacking or infection of humans from this quarter can by and large be ruled out, provide strong support for Koch’s conception of the dominant importance of infection from one human to another in the spread of tuberculosis in humans.

Seldom has an investigator been able to comprehend in advance with such clear-sightedness a new, unbroken field of investigation, and seldom has someone succeeded in working on it with the brilliance and success with which Robert Koch has done this. Seldom have so many discoveries of such decisive significance to humanity stemmed from the activity of a single man, as is the case with him.

One series of studies by him – indeed one of the most important – to which he has devoted a great part of his research from the outset until recently, namely his investigations and discoveries concerning tuberculosis, is singled out by the Professional Staff of the Royal Caroline Institute, as witness of its homage, with the award of this year’s Nobel Prize.

Geheimrat Robert Koch. In announcing that the Staff of Professors of the Royal Caroline Institute has awarded you this year’s Nobel Prize in Medicine for your work and discoveries concerning tuberculosis, I bring you the Staff’s homage.

Only solitary instances occur of one person on his own making so many fundamental and pioneering discoveries, as you have done.

By your pioneering research you have found out the bacteriology of tuberculosis, and written your name for ever in the annals of medicine.

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1905/ceremony-speech/

Koch was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1905 for his “pioneering research” in which he was said to have found out the bacteriology of tuberculosis. His award was for his investigations and discoveries in relation to TB, as stated by the Nobel Prize page:

Prize motivation: “for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis”

Tuberculosis (TB) is a serious illness affecting tissue, especially in the lungs. Robert Koch, who had conducted a range of important studies on illnesses caused by microorganisms, discovered and described the TB bacterium in 1882. He later studied tuberculin, a substance formed by tubercle bacteria. It was hoped it could be used as a cure for TB, but proved ineffective. Koch didn't believe there was a connection between TB in humans and animals, but he was not entirely correct.

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1905/koch/facts/

At no point during Mörnei's speech or in the Nobel Prize literature was it ever stated that Koch was awarded this prize because he had proven that the tuberculosis bacterium caused disease in humans. It was even admitted in a paper for Trends in Microbiology, which was celebrating the 100th anniversary of Koch’s Nobel Prize, that the award was not for Koch discovering the etiologic (i.e. causing or contributing to the development of a disease or condition) agent but for his work with TB:

100th anniversary of Robert Koch's Nobel Prize for the discovery of the tubercle bacillus

“One hundred years ago, Robert Koch (1843–1910; Figure 1) was honoured with the Nobel Prize for his groundbreaking work on tuberculosis. The laudation did not mention his discovery of the etiologic agent of tuberculosis specifically but rather emphasized the achievements of Koch in the fight against this threat.”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16112578/

Thus, it is stretching logic to conclude that the Nobel Prize award somehow shows that Koch proved the Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenic in humans when the relevant sources themselves do not make such a claim. Even Koch's own Nobel Prize speech presented much uncertainty surrounding the bacterium and how it supposedly spread.

Koch began his speech by acknowledging that, as recently as 20 years prior, tuberculosis was considered non-infectious. He stated that the reason it was now being accepted as contagious was due to his discovery of the bacterium. However, there was resistance to this conclusion and he lamented that it was taking a long time in order for his work to be accepted and for appropriate protective measures to be put in place. Koch felt that before he could discuss such measures, he needed to detail how the bacterium invaded humans. Koch presented two scenarios, neither of which were confirmed and were purely speculative:

Infection by tubercle bacilli which come from tuberculous people.

Bacteria that are contained in the milk and meat of tuberculous cattle.

Koch dismissed the second possibility based upon his own observations and experiments where the same tuberculosis bacterium found in cattle could not make humans sick. As stated previously, this was considered an embarrassing error for Koch as it is now claimed that he was proven wrong.

Koch then went on to discuss the contagiousness of the sputum from TB patients, noting that only those with illness of the larynx and lungs were of a concern. He believed that even “the smallest drops of mucus expelled into the air by the patient when he coughs, clears his throat, and even speaks, contain bacilli and can cause infection.” He broke down the risk based on what he called “open” and “closed” cases of TB. Those who were considered “open” were said to have more bacteria in their sputum and thus were a threat to spread TB while those who were “closed” were not a threat. However, Koch admitted that the “open” cases could live with their families for years without infecting anyone. He even pointed to the non-existence of infections among nursing staffs as they were either totally absent or so rare that it was seen as proof of the non-contagiousness of tuberculosis. Giving credence to the fact that living conditions had more to do with “infections” rather than the hypothetical spread of bacteria, Koch stated that unsanitary conditions and a lack of sunlight and air led to these “infections.” He even went so far as to point out that those who were poor and sleeping together in the same bed in worse living conditions had more “infections,” which led him to declare that TB was a disease of accommodation. Thus, according to Koch, tuberculosis people were only harmful if they were “open” cases and were living in poor unsanitary conditions:

The Current State of the Struggle against Tuberculosis

“Twenty years ago, tuberculosis, even in its most dangerous form, consumption, was still not considered infectious. Of course, the work of Villemin and the experimental investigations by Cohnheim and Salomonsen had already provided certain clues which suggested that this conception was false. But it was only with the discovery of the tubercle bacillus that the aetiology of tuberculosis was placed on a firm footing, and the conviction gained that this is a parasitic disease, i.e. an infectious, but also avoidable one.

In the first papers concerning the aetiology of tuberculosis I have already indicated the dangers arising from the spread of the bacilli-containing excretions of consumptives, and have urged moreover that prophylactic measures should be taken against the contagious disease. But my words have been un-heeded. It was still too early, and because of this they still could not meet with full understanding. It shared the fate of so many similar cases in medicine, where a long time has also been necessary before old prejudices were overcome and the new facts were acknowledged to be correct by the physicians.

However, quite gradually the understanding of the infectious nature of tuberculosis then spread, taking root ever more deeply, and the more the conviction of the dangerous nature of tuberculosis made headway, the more was the necessity of protecting oneself against it thrust on people.”

“But, before we come to answer this question, we must make perfectly clear to ourselves how infection is brought about in tuberculosis, i.e. how the tubercle bacilli invade the human organism; for all prophylactic measures against an infectious disease can only be directed towards preventing the germs of disease from invading the body.

In relation to tuberculosis infection so far only two possibilities have offered themselves: first, infection by tubercle bacilli which come from tuberculous people, and second, by those that are contained in the milk and meat of tuberculous cattle.

As a result of investigations which I made together with Schütz into the relation between human and bovine tuberculosis, we can dismiss this second possibility, or look upon it as being so small that this source of infection is quite overshadowed by the other. We arrived in effect at the conclusion that human and bovine tuberculosis are different from one another, and that bovine tuberculosis cannot be transmitted to a human. With regard to this latter point, I would, however, like to add, so as to obviate misunderstandings, that I refer only to those forms of tuberculosis which are of some account in the fight against tuberculosis as an epidemic, namely to generalized tuberculosis, and, above all, to consumption. It would take us too far here, if I were to go more closely into the very lively discussion which has developed over this question; I must keep this for some other occasion. I would just like to observe in addition to this that the re-examination of our investigations, which was undertaken in the Imperial Department of Health in Berlin with the greatest care and over a wide area, has led to a confirmation of my view, and that the harmlessness for humans of the bacilli of “pearl disease” is directly proved, in addition, by inoculating humans with material from it, as was done by Spengler and Klemperer. Consequently, only the tubercle bacilli coming from humans are of consequence in the battle against tuberculosis.

But the disease does not in all tuberculous patients take such forms that tubercle bacilli are discharged to a noteworthy extent. It is really only those suffering from tuberculosis of the larynx and lungs who produce and disseminate considerable quantities of tubercle bacilli in a dangerous way. But it is as well to note that not only is the secretion of the lung called sputum dangerous by reason of its bacillary content, but that, according to the investigations of Flügge, even the smallest drops of mucus expelled into the air by the patient when he coughs, clears his throat, and even speaks, contain bacilli and can cause infection.

We come therefore to this fairly sharp demarcation, that only those tuberculous patients comprise an important danger to the people around them, who suffer from laryngeal or pulmonary tuberculosis and have sputum which contains bacilli. This type of tuberculosis is designated “open” as opposed to “closed”, in which no tubercle bacilli are discharged into the environment.

But even in patients with open tuberculosis there are still distinctions to be made regarding the degree of danger due to them.

It can indeed very often be observed that such patients live for years with their families, without infecting any of them. Under some circumstances, in hospitals for consumptives infections among the nursing staff can be totally absent, or indeed so rare that it was even thought that in this was to be seen a proof of the non-contagiousness of tuberculosis. If, however, such cases are looked into more thoroughly, then it turns out that there are good reasons for the apparent lack of contagiousness. In such cases one is dealing with patients who are very careful where their sputum is concerned, who value the cleanliness of their home and their clothing, and in addition live in well-aired and well-lit rooms, so that the germs, taken up in air, can be rapidly carried away by the flow of air or killed by light. If these conditions are not fulfilled, then infection is not lacking in hospitals and the homes of the well-to-do, as experience teaches us every day. It becomes more frequent, the more unhygienically the patients handle their expectoration, the more there is a lack of light and air, and the more closely the sick are crowded together with the healthy. The risk of infection becomes particularly high if healthy people have to sleep with the sick in the same rooms, and especially, as still unfortunately happens with the poorer section of the population, in one and the same bed.

In the eyes of careful observers, this sort of infection has acquired such importance that tuberculosis has been called plainly, and quite justly, a disease of accommodation.

To recapitulate briefly, the circumstances relating to infection in tuberculosis are as follows.

Patients with closed tuberculosis are to be regarded as quite harmless. Also people suffering from open tuberculosis are harmless as long as the tubercle bacilli discharged by them are prevented from causing infection by cleanliness, ventilation, etc. The patient only becomes dangerous, when he is on his own unclean, or when, as the result of advanced disease, he becomes so helpless that he can no longer see to the adequate disposal of the expectorated material. At the same time the risk of the healthy being infected increases with the impossibility of avoiding the immediate neighbourhood of the dangerous patient, thus in crowded rooms and most particularly when these are not only overfull, but are badly ventilated and inadequately illuminated as well.”

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1905/koch/lecture/

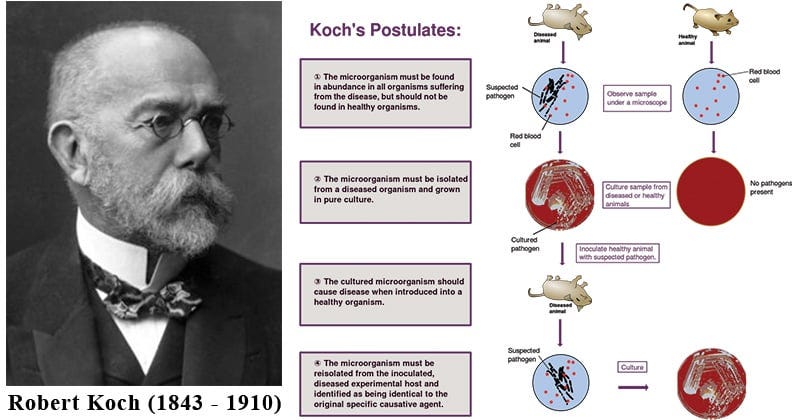

For those looking at this logically, finding the Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cases of disease is not proof that the bacterium is the cause of the disease in question. Correlation does not equal causation. A perfect example of this is finding firemen at the scene of a fire as they are almost always the first ones there. Yet this does not mean that the firemen were the cause of the fire and as we all know, they are only there in order to put the fire out. Thus, finding bacteria at the “fire” does not mean the bacteria caused the “fire” as they may very well be there to put the “fire” out. However, correlating the presence of the bacterium with cases of the disease and claiming it as the cause was exactly what Koch did when developing his conclusions. He had no evidence that the TB bacterium made humans sick with the same symptoms of disease, no proof of infection, and he could only speculate as to how it supposedly spread. Koch knew that this was not sufficient proof which is why he established postulates that he considered necessary requirements in need of fulfillment in order to claim a micro-organism is a pathogen. These became known as Koch's Postulates and are as follows:

The microorganism must be found in abundance in all hosts suffering from the disease but should not be found in healthy hosts.

The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased host and grown in pure culture.

The cultured microorganism should cause the same symptoms of disease when introduced into a healthy host.

The microorganism must be re-isolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and shown to be identical to the original causative agent.

Did Koch satisfy his postulates in order to state that Mycobacterium tuberculosis causes the symptoms of tuberculosis in humans? If the first requirement is that the microorganism should not be found in the healthy, he clearly did not. In the paper from 1937 below, it is stated that Koch did indeed find the TB bacterium in the healthy, thus failing his first postulate:

This fact alone should have made Koch immediately doubt his conclusions of finding a pathogenic cause for TB. Even if he tried to justify finding a few cases of the bacteria in the healthy, little did he know how pervasive Mycobacterium tuberculosis is in the healthy population. The vast majority of the people the bacterium is found within are asymptomatic, i.e. free of disease, and never go on to have tuberculosis. Turning to Wikipedia once again, we find that 90% of TB cases are asymptomatic and of that, there is only a 10% chance of coming down with disease:

“About 90% of those infected with M. tuberculosis have asymptomatic, latent TB infections (sometimes called LTBI),[57] with only a 10% lifetime chance that the latent infection will progress to overt, active tuberculous disease.[58]”

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuberculosis

This was supported by the WHO, although they put the number at 5-10% of TB cases ever developing disease:

“About one-quarter of the world’s population has a TB infection, which means people have been infected by TB bacteria but are not (yet) ill with the disease and cannot transmit it.

People infected with TB bacteria have a 5–10% lifetime risk of falling ill with TB. Those with compromised immune systems, such as people living with HIV, malnutrition or diabetes, or people who use tobacco, have a higher risk of falling ill.”

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

This was also backed up by the CDC:

“However, not everyone infected with TB bacteria becomes sick. As a result, two TB-related conditions exist: latent TB infection and TB disease.

What is Latent TB Infection?

Persons with latent TB infection do not feel sick and do not have any symptoms. They are infected with M. tuberculosis, but do not have TB disease. The only sign of TB infection is a positive reaction to the tuberculin skin test or TB blood test. Persons with latent TB infection are not infectious and cannot spread TB infection to others.

Overall, without treatment, about 5 to 10% of infected persons will develop TB disease at some time in their lives. About half of those people who develop TB will do so within the first two years of infection. For persons whose immune systems are weak, especially those with HIV infection, the risk of developing TB disease is considerably higher than for persons with normal immune systems.”

https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/general/ltbiandactivetb.htm

Koch could not fulfill his very first postulate as the TB bacterium is regularly found in those who are disease-free. Thus, he did not prove that the TB bacterium causes tuberculosis. If anything, it can be seen that Mycobacterium tuberculosis is rarely associated with symptoms of the disease.

However, if the above information is not enough to seal the deal that Robert Koch never proved Mycobacterium tuberculosis causes disease in humans, maybe this next piece of information will. As a final nail in the coffin to this claim, the reprinting of Koch's 1882 paper had a very interesting revelation in a commentary by the journal. At the end of the paper, it is revealed that Koch could not definitively prove the bacterium as the cause of disease in humans:

The etiology of tuberculosis

“Koch was also fortunate that the strain of tubercle bacillus that is pathogenic for humans can be transferred so readily to guinea pigs. Without an experimental animal which showed characteristic symptoms upon inoculation with tuberculous material, his work would have been much harder. He might have cultured the organism successfully, but the actual proof that this organism was the causal agent for tuberculosis would have been much more difficult. It should be noted that in this paper he does not have a final proof that the organism he has isolated in pure culture is really the cause of human tuberculosis. This could only be done by making inoculations in humans. Since this cannot be done, we can only infer that the isolated organism causes the human disease. Such a dilemma is always with the investigator of human diseases. He must learn to live with it.”

https://materiais.dbio.uevora.pt/Micro/Classicos.pdf

Robert Koch did not win the Nobel Prize for proving that the Mycobacterium tuberculosis was pathogenic in humans. He was awarded for his work with tuberculosis. No mention was ever made that Koch had proved the bacterium as the causative agent of the disease it was associated with. Thus, the claim that the Nobel Prize award is proof of Koch discovering a pathogenic cause is entirely fallacious.

If Koch was an honest researcher, he would have acknowledged that he could not even fulfill his first Postulate. He would have seen that the lack of infections and contagious outbreaks in those who were around the severely ill were clear signs that the bacterium was not transmissible. He would have realized that his failure to “cure” TB with tuberculin was due to the inaccuracy of his pathogenic premise. He would have admitted that all he did was discover a micro-organism found in many people whether sick or healthy. However, Robert Koch was not an honest researcher and his deception has led others to make false and erroneous claims about his work. It's time to set the record straight.

Here is a related article I did for viroLIEgy.com dealing with Koch's Postulates and asymptomatic carriers:

https://viroliegy.com/2022/10/10/kochs-postulates-and-the-great-asymptomatic-escape/

has been on fire recently, not that this should come as a surprise to anyone. In the first of two amazing articles, Eric Coppolino writes an open letter to JJ Couey, science advisor to the Children's Health Defense, explaining to Couey his own journey into discovering the "virus” lie:In the second article, Eric targets Couey's boss Robert Kennedy Jr. and takes the “no virus” issue to the next level by presenting an air-tight case for why our position should be heard and given equal opportunity and promotion. Excellent work! 👏

had a very entertaining and informative in-depth look into the electronic microscopy scam as well as asking the pertinent question of which came first, the "virus” or the egg?: tears into the issues relating to exposure to aluminum in the vaccines and provides advice on how to protect oneself from this toxic substance:Not to be outdone, Dr. Mark Bailey crushed it per usual by providing a fascinating interview exposing the “virus” lie:

Thanks for the TB!

It's a great conversation-opener.

Something tells me that Dr. JJ may not last a long time as a consultant of RFKJr's CHD. He seens to be talking out of the party line.

This current melodrama about Jordon von Pfizer (who in a previous life may have been Prince-Elector of the Palatinate) is unhinging the foundation of everything. Full blast psyop warfare on the dissidents.

It's incredible to watch.

I think this evening they will come out admitting it was all fake, to measure people's gullibility.

What a macabre theater this is!

I'm sure I read something criminally fraudulent that was then hushed over once on Koch but cant find it. Of course the 'medical treatments can be seen as such' but were not, as the reputation of scientific medicine had to be protected.

Some more on the topic here

http://www.whale.to/v/golden_calf.html#Chapter_8:_TUBERCULOSIS:_KOCH_AND_HIS_IMITATORS_