According to the mainstream narrative, “antibodies” are proteins that react to antigens—substances identified as foreign, such as toxins, proteins, peptides, or polysaccharides. The prevailing pseudoscientific hypothesis claims that each “antibody” binds to a specific antigen, like a lock and key. In the case of “SARS-COV-2,” “antibodies” said to be specific to the spike protein are believed to form either after “infection” with the “virus” or through vaccination, which allegedly programs the body to produce the spike protein via mRNA instructions. Once enough “antibodies” accumulate, they are said to be detectable through “antibody” tests. However, detection is claimed to occur only after an “infection” has run its course, since the body is thought to take time to generate an “antibody” response. Unlike HIV, where “antibody” tests supposedly indicate an active “infection,” we are told that “Covid antibody” tests (and those for other “viruses”) serve only to determine past exposure and assess whether an individual has developed some degree of “immunity.”

“Antibody tests should not be used to diagnose a current infection with the virus that causes COVID-19. An antibody test may not show if you have a current infection, because it can take 1 to 3 weeks after the infection for your body to make antibodies.”

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/testing.html

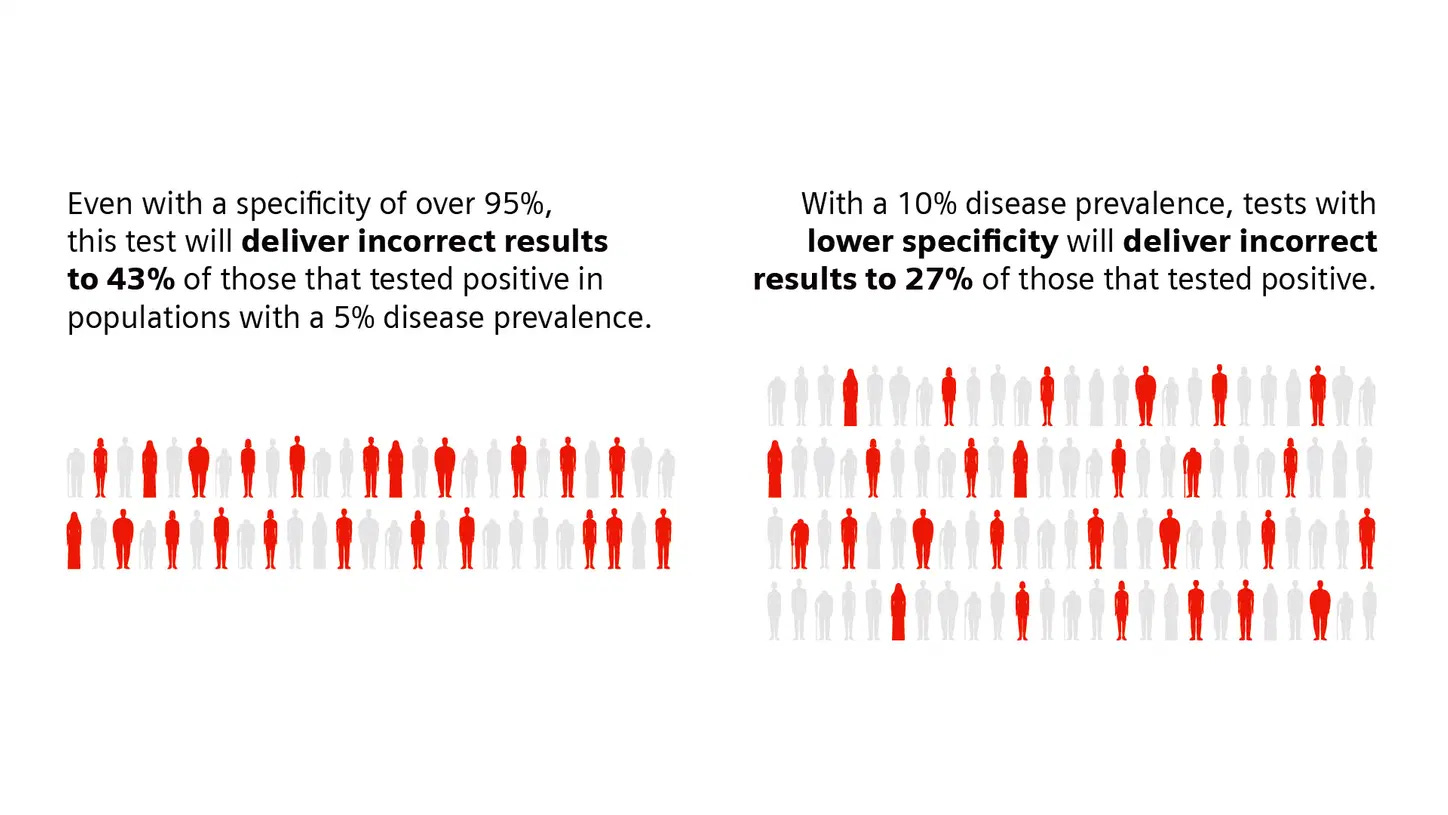

In order for “antibody” test results to have any sort of meaing, specificity—refering to an “antibody’s” ability to recognize and bind exclusively to a single, unique antigen—is absolutely essential. Many assume these tests are highly accurate and specific, but the reality is far more complicated. While marketed as detecting specific “antibodies,” cross-reactivity—where “antibodies” bind to unintended antigens—is a well-documented issue. This undermines claims of specificity, making test results questionable at best. Although such limitations are rarely emphasized, even the CDC acknowledges them in its own reports.

Antibody Testing Guidelines

“Testing for antibodies that indicate prior infection could be a useful public health tool as vaccination programs are implemented, provided the antibody tests are adequately validated to detect antibodies to specific proteins (or antigens). Although an antibody test can employ specific antigens, antibodies developed in response to different proteins might cross-react (i.e., the tests might detect antibodies they are not intended to detect), and therefore, might not provide sufficient information on the presence of antigen-specific antibodies. For antibody tests with FDA EUA, it has not been established whether the antigens employed by the test specifically detect only antibodies against those antigens and not other antigens.”

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antibody-tests-guidelines.html

The CDC explicitly states that no FDA EUA-approved “SARS-COV-2 antibody” test has been definitively established to detect only “antibodies” specific to “SARS-COV-2” antigens. This raises serious concerns about the validity of these tests, as cross-reactivity with “antibodies” from other “infections” would lead to misleading results. This issue becomes even more apparent when considering that there are no properly purified and isolated “viruses” to serve as definitive standards for “antibody” test calibration—just as there are no directly isolated “antibodies” proven to be specific to “SARS-COV-2.”

Making matters worse, PCR—an already problematic test—is routinely used to confirm “positive” samples in “antibody” test validation studies. This means that one unvalidated, inherently flawed test is being used as the benchmark for another unvalidated, inherently flawed test, creating a fraudulent circular validation process that lacks independent confirmation of accuracy.

EUA Authorized Serology Test Performance

“The performance of these tests is described by their "sensitivity," or their ability to identify those with antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (true positive rate), and their "specificity," or their ability to identify those without antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (true negative rate). A test's sensitivity can be estimated by determining whether or not it is able to detect antibodies in blood samples from patients who have been confirmed to have COVID-19 with a nucleic acid amplification test, or NAAT. In some validation studies of these tests, like the one the FDA is conducting in partnership with the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), the samples used, in addition to coming from patients confirmed to have COVID-19 by a NAAT, may also be confirmed to have antibodies present using other serology tests. A test's specificity can be estimated by testing large numbers of samples collected and frozen before SARS-CoV-2 is known to have circulated to demonstrate that the test does not produce positive results in response to the presence of other causes of a respiratory infection, such as other coronaviruses.

These estimates of sensitivity and specificity are just that: estimates. They include 95% confidence intervals, which are the range of estimates we are about 95% sure a test's sensitivity and specificity will fall within given how many samples were used in the performance validation. The more samples used to validate a test, the smaller the confidence interval becomes, meaning that we can be more confident in the estimates of sensitivity and specificity provided.

Tests are also described by their Positive and Negative Predictive values (PPV and NPV). These measures are calculated using a test's sensitivity, its specificity, and using an assumption about the percentage of individuals in the population who have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (which is called "prevalence" in these calculations). Every test returns some false positive and false negative results. The PPV and NPV help those who are interpreting these tests understand, given how prevalent individuals with antibodies are in a population, how likely it is that a person who receives a positive result from a test truly does have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and how likely it is that a person who receives a negative result from a test truly does not have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. The PPV and NPV of a test depend heavily on the prevalence of what that test is intended to detect. Because all tests will return some false positive and some false negative results, including tests that detect antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, broad use of the tests, when not appropriately informed by other relevant information, such as clinical history or diagnostic test results, could identify too many false-positive individuals.”

On top of these issues, there is no established correlation between “antibody” levels and “protection” from “infection” or disease, referred to as the correlation of protection. In other words, there is no defined threshold for how many “antibodies,” if any, are needed to prevent illness. Without a clear link between “antibody” presence and “immunity,” these tests fail to provide meaningful or actionable information. Ultimately, this calls into question the entire premise on which “antibody” testing is based, making the results from these tests meaningless.

The Flawed Science of Antibody Testing for SARS-CoV-2 Immunity

“The early consumer tests’ accuracy was unproven, making the results somewhat dubious. More fundamentally, the so-called correlates of protection were unknown. Which specific antibodies guarded against SARS-CoV-2 reinfection? How high did their levels need to be? And how long would they provide a reliable defense?”

“Therefore, the agency in its May 19 communication stated that “results from currently authorized SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests should not be used to evaluate a person’s level of immunity or protection from COVID-19 at any time, and especially after the person received a COVID-19 vaccination.”

“The problem isn’t simply that the tests weren’t designed to assess immunity, experts told JAMA. It’s also that the protective antibodies and their thresholds still haven’t been fully worked out.”

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2785530

Specificity in testing is crucial because, without high specificity, an “antibody” test cannot reliably determine whether someone was exposed to “SARS-COV-2” or to an entirely different antigen. If an “antibody” reacts to multiple, unrelated proteins, then a positive test result does not confirm prior “infection” with “SARS-COV-2,” or any other “virus” for that matter. A lack of specificity renders these tests unreliable for both individual diagnosis and public health policy.

Furthermore, this issue extends beyond testing—it directly contradicts the narrative that vaccines produce highly specific “immune” responses. If “SARS-COV-2 antibodies” can bind to multiple antigens, then how can it be claimed that vaccines induce “immunity” against a specific “virus?” If these same “antibodies” are present due to exposure to other antigens, then a vaccine-induced “immune” response cannot be distinguished from natural exposure to unrelated substances or “pathogens.” This should raise serious doubts about the claimed effectiveness of these injections and whether any measured “antibody” response is truly protective or merely a generic reaction that has been misinterpreted.

This lack of specificity of “antibodies” is not theoretical—it is well-documented in the “scientific” literature. Numerous studies have reported cross-reactivity in “SARS-COV-2 antibody” tests, where “antibodies” claimed to be specific to the “virus” also bind to antigens from many other sources. As specificity is an essential tenet of “antibody” research and the prevailing “immunity” narrative, let's examine these studies and find out exactly how nonspecific these “antibodies” truly are.

We begin this examination with a study published in June 2020 which highlighted the importance of understanding cross-reactivity, stating that it is crucial for properly interpreting serologic tests, such as serosurveys and clinical “antibody” tests. To gain a better understanding of this, the researchers evaluated serologic reactivity using pre-2019 archival blood serum samples (“pre-pandemic”) and samples from a community highly affected by “SARS-COV-2” in April 2020. In other words, half of the blood and serum samples tested came from before “SARS-COV-2” supposedly existed. The researchers tested IgG, IgM, and IgA reactivity against spike proteins from “SARS-COV-2,” “MERS,” “SARS-COV-1,” “OC43,” and “HKU1” using twelve previously reported ELISAs. Their results showed that “antibodies” supposedly specific to “SARS-COV-2” also reacted with “MERS” and “SARS-COV-1,” revealing a lack of specificity to the intended “viral” target.

The researchers tried to explain away this cross-reactivity by suggesting that individuals who strongly seroconverted after “SARS-COV-2 infection” could have “antibodies” that are universally reactive to multiple “Betacoronaviruses,” including “MERS” and “SARS-COV-1.” They also cautioned that in regions with higher prevalence of “MERS” and “SARS-COV-1,” archival sera should be considered to adjust estimates of seropositivity, highlighting the potential issue of misinterpreting “antibody” results due to cross-reactivity. Despite the excuses presented, the evidence clearly showed that the so-called specific “antibodies” to “SARS-COV-2” were binding to its relatives.

Serologic cross-reactivity of SARS-CoV-2 with endemic and seasonal Betacoronaviruses

“Furthermore, knowledge of cross-reactivity is necessary to understand and properly interpret results from serologic studies such as serosurveys and clinical antibody tests (13, 14). Previous research has shown minimal cross-reactivity between RBD domains from differing coronaviruses; however, these studies largely ignore the rest of the spike protein, which will be an important consideration for identification of potential therapeutic antibodies and can be used in vitro to help identify polyclonal responses that are not detected with RBD alone (15).

Here, we evaluated the serologic reactivity of pre-pandemic archival blood serum samples (pre-2019) and samples collected in April 2020 from a community highly affected by SARS-CoV-2. Utilizing twelve previously reported ELISAs (15), we tested IgG, IgM and IgA reactivity against spike proteins from SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, HCoV-OC43, and HCoV-HKU1 (Fig. 1).”“When comparing serum from healthy volunteers collected pre-2019 (archival controls) to those from a high-exposure community, we observe that SARS-CoV-2 antibodies react intermediately with MERS and SARS-CoV spike proteins. The mean ELISA signal intensity is significantly greater for both MERS and SARS-CoV when comparing archival controls versus the high-incidence community.”

“Given the low seroprevalence of SARS-CoV and MERS outside of their endemic regions, and the significantly lower reactivity of SARS-CoV-2 patient sera to SARS-CoV and MERS spike proteins, it is likely that any reactivity between the pandemic SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and MERS/SARS-CoV endemic viruses would result in minimal noise between SARS-CoV-2 signal and endemic coronavirus signal in serological assays. In countries with a higher prevalence of MERS & SARS-CoV, researchers should include thorough analysis of archival patient sera (pre-2019), including sera from known SARS-CoV and MERS convalescent patients, to properly analyze the resulting data and adjust any estimates of seropositivity as needed. No clinical serology studies of SARS-CoV-2 immunity in populations previously infected with either SARS or MERS have yet emerged.

Additionally, individuals who have strongly seroconverted after SARS-CoV-2 infection, and who display cross-reactivity for both MERS and SARS-CoV spike proteins, are of great interest for translational study. These individuals could potentially harbor antibodies that are universally reactive to multiple Betacoronaviruses and, if these antibodies are functional for neutralization, could be important to identify to inform the development of novel therapeutics or vaccines.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7315998/

In August 2020, a study found that dengue “antibody” tests also show cross-reactivity with “SARS-COV-2 antibodies.” The researchers detected 12 positive dengue cases (21.8%) out of 55 “COVID-19” patients using the dengue lateral-flow rapid test. Additionally, 95 dengue patient samples from before September 2019 showed that 22% (21 out of 95) tested positive or equivocal for “SARS-COV-2” serology targeting the spike (S) protein, compared to just 4% (4 out of 102) in controls (P = 1.6E−4). This study supported the idea of cross-reactivity between “dengue virus” and “SARS-COV-2,” which the researchers warned could lead to “false positives” in both dengue and “COVID-19” tests. The fact that cross-reactivity was observed — with dengue” antibody” tests showing false positives in “Covid” patients and “SARS-COV-2 antibody” tests showing positives in “pre-pandemic” dengue patients — highlights the lack of specificity in both tests.

Potential Antigenic Cross-reactivity Between Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Dengue Viruses

Results

Using the dengue lateral-flow rapid test we detected 12 positive cases out of the 55 (21.8%) COVID-19 patients versus zero positive cases in a control group of 70 healthy individuals (P = 2.5E−5). This includes 9 cases of positive immunoglobulin M (IgM), 2 cases of positive immunoglobulin G (IgG), and 1 case of positive IgM as well as IgG antibodies. ELISA testing for dengue was positive in 2 additional subjects using envelope protein directed antibodies. Out of 95 samples obtained from patients diagnosed with dengue before September 2019, SARS-CoV-2 serology targeting the S protein was positive/equivocal in 21 (22%) (16 IgA, 5 IgG) versus 4 positives/equivocal in 102 controls (4%) (P = 1.6E−4). Subsequent in-silico analysis revealed possible similarities between SARS-CoV-2 epitopes in the HR2 domain of the spike protein and the dengue envelope protein.

Conclusions

Our findings support possible cross-reactivity between dengue virus and SARS-CoV-2, which can lead to false-positive dengue serology among COVID-19 patients and vice versa. This can have serious consequences for both patient care and public health.

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/73/7/e2444/5892809

In November 2020, researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and University College London “accidentally” discovered that some individuals who were never diagnosed with “SARS-COV-2” had “antibodies” that cross-reacted with the “virus” and other “coronaviruses” associated with the common cold. To confirm their findings, they analyzed over 300 blood samples from 2011 to 2018. While most samples contained “antibodies” to common cold “coronaviruses,” a subset also showed cross-reactivity with “SARS-COV-2.” This was found in 5.3% of adults, 10% of pregnant women, and 44% of children—especially those aged 6 to 16.

Prepandemic coronavirus antibodies may react to COVID-19

SARS-CoV-2 and the common cold

The first study, published late last week in Science, was the result of an accidental discovery by researchers at Francis Crick Institute and University College London while testing the performance of sensitive COVID-19 antibody tests by comparing the blood of COVID-19–infected donors with that of those who had not had the disease.

They found that blood samples from some noninfected donors—particularly children—contained antibodies that could recognize both SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and other common coronaviruses, such as those responsible for the common cold.

To confirm their results, the researchers analyzed more than 300 blood samples collected from 2011 to 2018. While almost all samples had antibodies against coronaviruses that cause the common cold, 16 of 302 adults (5.3%) had antibodies that would recognize SARS-CoV-2—regardless of whether they had recently had a cold. Only 1 of an additional 13 adult blood donors (7.7%) recently infected with other coronaviruses had cross-reactive antibodies. Of samples from 50 pregnant women, 5 (10%) had such antibodies.

In contrast, 21 of 48 children aged 1 to 16 (44%) had cross-reactive antibodies, with those aged 6 to 16 most likely to have them.

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/73/7/e2444/5892809

In June 2021, researchers conducted a retrospective study using archived serum and EDTA whole blood samples collected from 2010 to 2018. When testing 13 different “Covid-19 antibody” rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), they found significant cross-reactivity with malaria, schistosomiasis, and dengue. Overall cross-reactivity was 18.5%, with rates of 20.3% for malaria, 18.1% for schistosomiasis, and 7.5% for dengue. Among the different RDT products, cross-reactivity ranged from 2.7% to 48.9%. The researchers warned of potential reliability issues when using these tests in regions where these diseases are prevalent.

COVID-19 Antibody Detecting Rapid Diagnostic Tests Show High Cross-Reactivity When Challenged with Pre-Pandemic Malaria, Schistosomiasis and Dengue Samples

A retrospective study was performed on archived serum (n = 94) and EDTA whole blood (n = 126) samples obtained during 2010–2018 from 196 travelers with malaria (n = 170), schistosomiasis (n = 25) and dengue (n = 25). COVID-19 Ab RDTs were selected based on regulatory approval status, independent evaluation results and detecting antigens. Among 13 COVID-19 Ab RDT products, overall cross-reactivity was 18.5%; cross-reactivity for malaria, schistosomiasis and dengue was 20.3%, 18.1% and 7.5%, respectively. Cross-reactivity for current and recent malaria, malaria antibodies, Plasmodium species and parasite densities was similar. Cross-reactivity among the different RDT products ranged from 2.7% to 48.9% (median value 14.5%). IgM represented 67.9% of cross-reactive test lines. Cross-reactivity was not associated with detecting antigens, patient categories or disease (sub)groups, except for schistosomiasis (two products with ≥60% cross-reactivity). The high cross-reactivity for malaria, schistosomiasis and—to a lesser extent— dengue calls for risk mitigation when using COVID-19 Ab RDTs in co-endemic regions.

As can be seen, in the first year of the “pandemic” alone, it was demonstrated and established that the so-called specific “SARS-COV-2 antibodies” not only cross-reacted with other “coronaviruses,” but also with dengue, malaria, and schistosomiasis. Not to be outdone, in September 2022, an article came out discussing the findings of a study that examined cross-reactivity between “SARS-COV-2 spike protein-specific antibodies” and various other substances. It was reported that the researchers found that the supposedly specific “antibodies” reacted with the DTaP vaccine, E. faecalis bacteria (which is a common human gut microbe), Epstein-Barr “virus,” and Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacterium associated with Lyme disease). They also noted cross-reactivity with many food items such as milk, gliadin toxic peptide, pea protein, α+β casein, soy, lentil lectin, and roasted almond, with the strongest reactivity found in broccoli, soybean, pork, rice endochitinase, cashew, and gliadin toxic peptide. The researchers attempted to frame this cross-reactivity as a “protective” factor, claiming it explains why people did not experience severe disease when encountering “SARS-COV-2 variants.”

Food, vaccines, bacteria, and viruses may all prime our immune system to attack SARS-CoV-2

“SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-specific antibodies were found to react most with the DTaP vaccine and, to a lesser degree, with E. faecalis bacteria, which is a common human gut microbe. A lesser reaction was observed against EBV Ab to Early Antigen D (EBV-EAD), EBV-Nuclear Antigen (EBNA) and B. burgdorferi. No reaction was observed against BCG, measles, E. coli CdT, EBV Viral Capsid Antigen Antibody (EBV-VCA), and Varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

Milk, gliadin toxic peptide, pea protein, α+β casein, soy, lentil lectin, and roasted almond were found to react with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein antibody. Additionally, in the case of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein antibody, the strongest reaction was found with broccoli, soybean, pork, rice endochitinase, cashew, and gliadin toxic peptide.”

“The overall reaction of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein monoclonal antibody with the DTaP vaccine was found to be most potent. In contrast, less strong reactions were observed with other vaccines and common viral and bacterial antigens, such as E. faecalis and herpesviruses. Surprisingly, no reaction was observed against BCG vaccine antigens. Many food proteins and peptides were found to share homology with SARS-CoV-2 proteins.”

“The current study's findings indicated that cross-reactivity induced via DTaP vaccines, along with common viruses (e.g., herpesviruses) and bacteria (e.g., E. faecalis, E. coli) protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Furthermore, the cross-reactivity between food antigens and different pathogens explains why most of the global population, repeatedly exposed to different SARS-CoV-2 variants, were not severely infected.”

Digging a bit deeper by examining the actual study, we find that the researchers acknowledged that it has been shown that “SARS-COV-2 antibodies” share homology and cross-react with vaccines, other “viruses,” common bacteria and many human tissues. Inspired by this evidence, they set out to react monoclonal and polyclonal “antibodies” against “SARS-COV-2” spike protein and nucleoprotein with 15 different bacterial and “viral” antigens and 2 different vaccines, BCG and DTaP, as well as with 180 different food peptides and proteins. They also performed BLAST searches in genomic databases to find the degree of identity between “SARS-COV-2” and the other subjects, revealing that “SARS-COV-2” sequences shared 50–100% identity with various “viruses,” while an additional set of peptide sequences had 30–49% similarity. Furthermore, numerous peptides from common dietary sources exhibited 50–73% identity with “SARS-COV-2” sequences, often matching multiple regions of the so-called “SARS-COV-2” genome.

Despite these findings demonstrating a broad lack of specificity, the researchers framed the cross-reactivity as beneficial, arguing that it may have provided “protection” against “Covid-19.” They asserted that exposure to DTaP vaccines, common “herpesviruses,” gut bacteria like E. faecalis and E. coli, and everyday food antigens could explain why a large portion of the global population remained asymptomatic or had mild symptoms despite repeated exposure to alleged “SARS-COV-2 variants.” However, they ultimately conceded that cross-reactivity is typically viewed as problematic, highlighting the contradictory nature of their interpretation.

Reaction of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies with other pathogens, vaccines, and food antigens

“It has been shown that SARS-CoV-2 shares homology and cross-reacts with vaccines, other viruses, common bacteria and many human tissues. We were inspired by these findings, firstly, to investigate the reaction of SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibody with different pathogens and vaccines, particularly DTaP. Additionally, since our earlier studies have shown immune reactivity by antibodies made against pathogens and autoantigens towards different food antigens, we also studied cross-reaction between SARS-CoV-2 and common foods. For this, we reacted monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and nucleoprotein with 15 different bacterial and viral antigens and 2 different vaccines, BCG and DTaP, as well as with 180 different food peptides and proteins. The strongest reaction by SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were with DTaP vaccine antigen, E. faecalis, roasted almond, broccoli, soy, cashew, α+β casein and milk, pork, rice endochitinase, pineapple bromelain, and lentil lectin.”

Amino acid sequence similarity between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and other viruses and food antigens

“We used BLAST to find the degree of identity between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and other viruses and pathogens, including HSV-1, HSV-2, EBV, CMV, HHV-6, measles, VZV and Borrelia burgdorferi. SARS-CoV-2 proteins shared a significant number of peptides with each of these pathogens, as can be seen in Table 1A and Table 1B. These SARS-CoV-2 sequences shared 50-100% identity with different viruses. An almost similar number of peptide sequences with identity percentages ranging from 30 to 49% were also observed but are not shown in these tables. Similar to SARS-CoV-2 homology with other viruses and pathogens, we used BLAST to find a significant number of peptides from different foods that are consumed on a daily basis which shared 50-73% identity with SARS-CoV-2 sequences. These foods were peanuts, almonds, wheat, milk, rice, lentil and pineapple (see Table 2A and Table 2B). In both cases these subject sequences actually made a match with more than one section of the SARS-CoV-2 sequences; the multiple matches are indicated by asterixes in Tables 1(A & B) and 2(A & B).”

Conclusion

“The findings presented in this manuscript indicate that cross-reactivity elicited by DTaP vaccines in combination with common herpesviruses to which we are exposed at an early age, bacteria that are part of our normal flora (E. faecalis, E. coli), and food that we consume on a daily basis may be keeping some individuals safe from COVID-19 in different parts of the world. This cross-reactivity between different pathogens and food antigens may explain why a significant percentage of the population who were repeatedly exposed to different variants of SARS-CoV-2 never became seriously ill. Additional in vivo and in vitro experiments are needed to clarify whether or not this cross-protection was due to the presence of cross-reactive antibodies or long-term memory T and B cells in the blood. Although cross-reactivity is mainly viewed as negative, this cross-reaction involving vaccine antigens, common viruses and food antigens may be protective.”

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1003094/full

In October 2022, a study examined the cross-reactivity of so-called “SARS-COV-2-specific antibodies.” Researchers analyzed “antibody” responses in individuals who had never been diagnosed with “SARS-COV-2” using sera samples collected before 2017 from both healthy individuals and those with various acute or chronic conditions. Their findings revealed cross-reactivity with antigens from common human “viruses,” including seasonal, persistent, latent, and chronic infections. Notably, “SARS-COV-2” S1 and S2 cross-reactive “antibodies” were readily detectable in “pre-pandemic” samples.

The study acknowledged prior research showing cross-reactivity between endemic common cold “coronaviruses” (HCoVs) and “SARS-COV-2.” However, whether this cross-reactivity impacted “Covid-19” disease outcomes positively or negatively remained unresolved. Additionally, the researchers observed shifts in “antibody” responses to “respiratory syncytial virus (RSV),” “cytomegalovirus (CMV),” and “herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1)” in patients with severe “Covid-19.” Their data demonstrated that IgG “antibody” responses to distinct epitopes of the “SARS-COV-2” spike protein were common even in the “uninfected” population, and similar reactivity was found in serological studies of “Covid-19” patients.

Upon analyzing the “SARS-COV-2” S protein epitopes, sequence alignment across human “viral” antigens revealed frequent detection of other “coronaviruses” (HCoVs, including “SARS-COV-1,” “OC43,” and “HKU”). Significant homology was also found between these S epitopes and antigens from “herpesviruses,” “papillomaviruses,” and respiratory “viruses” such as influenza. Specifically, high sequence similarity was noted between “SARS-COV-2” S protein epitopes and antigens from “influenza A H1N1,” “respiratory syncytial virus type B (HRSV-B),” “rhinoviruses 2/16,” “adenovirus A type 12,” and various “papillomaviruses.” The researchers highlighted that “herpes viral” antigens could act as direct molecular mimics of S antigenic determinants. They concluded that heterologous “immunity” between epitopes of various common human “viruses” and “SARS-COV-2” S is widespread.

Recognizing a potential role for “autoimmunity,” the researchers also analyzed the human proteome, identifying at least 63 human proteins with highly similar antigenic determinants to “SARS-COV-2” S epitopes. They found that patients with severe “Covid-19” had higher IgG titers against the “OC43” S protein and confirmed heterologous “immunity” between “SARS-COV-2” and certain bacteria. Cross-reactive “antibodies” with “SARS-COV-2” proteins were also elicited by exposure to “poliovirus,” pneumococcal bacteria, the mumps “virus” (via the MMR vaccine), “measles” fusion glycoprotein, and even “Ebola” and “HIV-1” glycoproteins.

Differential patterns of cross-reactive antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein detected for chronically ill and healthy COVID-19 naïve individuals

“By profiling the antibody response in COVID-19 naïve individuals with a diverse clinical history (including cardiovascular, neurological, or oncological diseases), we identified 15 highly antigenic epitopes on spike protein that showed cross-reactivity with antigens of seasonal, persistent, latent or chronic infections from common human viruses. We observed varying degrees of cross-reactivity of different viral antigens with S in an epitope-specific manner. The data show that pre-existing SARS-CoV-2 S1 and S2 cross-reactive serum antibody is readily detectable in pre-pandemic cohort. In the severe COVID-19 cases, we found differential antibody response to the 15 defined antigenic and cross-reactive epitopes on spike. We also noted that despite the high mutation rates of Omicron (B.1.1.529) variants of SARS-CoV-2, some of the epitopes overlapped with the described mutations.”

“The preference of the immune system to recall existing memory cells, rather than stimulate a de novo response when encountering a novel but closely related antigen is referred to as immune imprinting, historically known as original antigenic sin11. Overall, immune imprinting would lead to enhanced immunity, whereas established pre-immunity may also increase cross-reactive antibody response towards epitopes that are shared between the current and the previously encountered antigen12,13. Studies have observed cross-reactivity between endemic common cold human coronaviruses (HCoVs) and SARS-CoV-214,15,16,whereas whether this cross-reactivity17,18 is beneficial or detrimental to COVID-19 disease is not clear14,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Cross-reactivity through heterologous immunity may arise through recognition of identical antigenic epitopes shared by different pathogens, or through recognition of unrelated epitopes owing to cross-reactivity of individual T and B cell receptors26. Shifts in antibody response to respiratory syncytial virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) were noted in patients with severe COVID-1927.”

Cross-reactive immune response to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in COVID-19 naïve people

“We used a high throughput random peptide phage display method (MVA)33,34 to investigate potential cross-reactive antibody epitopes on SARS-CoV-2 S antigen in a cohort of SARS-CoV-2 unexposed (= COVID-19 naïve, also unvaccinated) individuals (n = 538, Table 1). Our discovery cohort of COVID-19 naïve included sera samples collected before 2017 from both, healthy individuals (Ctrl) and people diagnosed with various acute illnesses and chronic conditions (Case) to reflect the overall diversity of general population (Table 1). The mean age in case sub-cohorts of adults varied from 24 to 69 years, and the proportion of men varied between 20 and 84% for most sub-cohorts (Table 1).

Using MVA we defined 15 highly antigenic epitopes on the S protein, of which ten were on subunit 1 (S1) and five on subunit 2 (S2) (Fig. 1 and Table 2). The majority of these epitopes (epitopes S1.1 to S2.4) were exposed on the exterior surface of SARS-CoV-2 S trimer (Fig. S2A). Seven of the 15 identified epitopes were partially overlapping with epitopes previously reported for COVID-19 unexposed individuals52 with an average overlap of 60% per epitope (Table 2). Epitopes S2.2 and S2.5 colocalised precisely with antigenic determinants reported by others, whereas epitope S1.8 extended to a more C-terminal region (amino acids 570–582) (Table 2). Furthermore, almost half of resolved epitopes (S1.8, S1.9, S1.10, S2.1, S2.2, S2.3, and S2.5) mapped to antigenic regions of S against which immune response has been detected in asymptomatic, mild, and severe COVID-19 cases (Table 2 and27,55,56,57). In good agreement with published data from SARS-CoV-2 proteome-based peptide arrays61, we found that linear peptides from these studies that contained our resolved epitopes on S protein showed differential seroreactivity in naïve, mild and severe COVID-19 samples (Fig. S3).”

“Collectively, these data suggest that IgG antibody responses to distinct epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 S protein is common across the naïve population and reactivity to the same antigenic regions is detected by serostudies of COVID-19 patients.”

Epitopes on SARS-CoV-2 S protein identified in COVID-19 naïve sera are linked to heterologous pathogens

“Next, we wanted to know whether cross-strain or cross-species immunity could be behind the observed epitope-specific pre-existing anti-SARS-CoV-2 S immunoreactivity. Sequence alignment analysis across human viral antigens resulted in frequent detection of other human coronaviruses (HCoVs, including SARS-CoV, OC43 and HKU) (Fig. 2A, Table S3). In addition, significant homology of the resolved S epitopes was also observed with common herpes-, papilloma-, and respiratory (including influenza) viral antigens (Table S3). For example, antigens of human cytomegalovirus (CMV) and of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), shared significant similarity with peptides containing epitopes S1.8 and S2.2 (Fig. 2A, Table S3) and these epitopes similar to CMV and EBV seroprevalence were also associated with age (Fig. S4A). Diagnostic serology measurements confirmed CMV and EBV seropositivity in analysed samples (Fig. S5A). However, in samples with CMV and EBV serology findings differential epitope-specific anti-S antibody response was evident (Figs. S6, S7), suggesting that herpesviral antigens can be direct molecular mimics of S antigenic determinants or indirectly associated with the heterologous immunity towards SARS-CoV-2 S. Epitopes S1.10 and S2.5 showed higher antibody responses in CMV + samples of both Ctrl and Case groups when compared to CMV-samples (Fig. S6), while seroresponse to epitopes S1.6, S1.8, S1.9 and S2.1 was significantly higher (S1.8, S1.9, S2.5) or lower (S1.6) in EBV + samples of Case group when compared to EBV + Ctrl group (Fig. S7). High sequence similarity was also found between epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 S protein and antigens of influenza A H1N1 (FLUA), respiratory syncytial virus type B (HRSV-B), rhinoviruses 2/16 (HRV-2/16), adenovirus A type 12 (HAdV-A) and most frequent papillomaviruses (HPV6 and HPV11, Fig. 2A, Table S3). By using dot-ELISA, we independently validated the IgG antibody response detected by MVA at a peptide level to common epitopes of CMV glycoprotein B and EBV VCA p18 proteins40 (Fig. S5B). Collectively, our data conclude that heterologous immunity between epitopes of various common human viruses and SARS-CoV-2 S can be common.

Recent evidence also suggests that the existence of pre-COVID-19 autoimmunity plays a role in disease outcome30,74. Therefore, we focused on the human proteome and identified at least 63 human proteins with highly similar antigenic determinants to resolved epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 S.”

“Similar to studies on influenza whereby the antibody response to older virus strains had profound and negative impacts on subsequent immunity13 cross-reactive antibody reactivity conferred by prior seasonal coronaviruses has widely been reported (ref in20,105). Higher titres of IgG against the HCoV-OC43 S protein were observed in patients with severe COVID-19106, concluding that such immunological imprinting by previous seasonal coronavirus infections negatively impacted on the antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 infection107.”

“In addition to cross-reactive epitopes with Omicron sublineages and also with endemic coronaviruses evidence of heterologous immunity between SARS-CoV-2 and pathogenic bacteria was reported108. Our study advances the concept showing that the cross-reactivity to epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 S protein with potential functional impacts could stem from the molecular mimicry with antigens of previously encountered other pathogens, including herpes-, papilloma-, adeno-, rhino-, influenza and other viruses (Fig. 2A). In good agreement with this, CMV seropositivity and age-related reduction in antibody titres against certain CMV antigens associated with the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection109. Conversely, several other studies suggest cross-protection against COVID-19 incidence and severity from vaccines of influenza28,110,111,112 and of other pathogens (polio, HIB, MMR, Varicella, PCV13, and HepA–HepB)28,110,111,112,113. These mechanisms may include generation of cross-protective antibodies through molecular mimicry. Cross-reacting antibodies with SARS-CoV-2 proteins elicited by poliovirus114 and pneumococcal bacteria115 have been identified, whereas for the mumps virus (via the MMR vaccine), the cross-reactivity of the vaccine antigen (measles fusion glycoprotein) with RBD of SARS-CoV-2 spike was suggested113. Additionally, monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 S RBD have been shown to cross-react with the Ebola glycoprotein and HIV-1 gp140116. Our data predict 15 cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 spike-like epitopes in common pathogens (Fig. 2A).”

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-20849-6

Finally, an editorial published in Frontiers Immunology in December 2024 highlighted how cross-reactive “immunity” existed prior to the “pandemic,” meaning that “antibodies” and “memory immune cells” elicited by other “pathogens” or antigens could also recognize “SARS-COV-2.” They explicitly stated that cross-reactivity is a fundamental feature of adaptive “immunity,” emphasizing that B and T cell receptors can recognize multiple different antigens, not just those from “SARS-COV-2.” The editorial reiterated that “SARS-COV-2 antibodies” and “immune” responses cross-react not only with common cold “coronaviruses” but also with unrelated “viruses,” bacteria, vaccines, and food antigens. This underscores that the “immune response” to “SARS-COV-2” is not uniquely specific to the “virus” itself.

They also noted that cross-reactivity can lead to unintended consequences, such as immunopathology and potential autoimmune reactions due to similarities between “viral” proteins and human tissue proteins. This reinforces the idea that “SARS-COV-2 antibodies” are not uniquely specific but can bind to a range of different targets, challenging the assumption that their presence is definitive evidence of exposure to “SARS-COV-2” alone.

Editorial: Cross-reactive immunity and COVID-19

“We now know that, unlike us, our immune system was not so surprised by SARS-CoV-2 since cross-reactive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Cross-reactive immunity is mediated by antibodies and memory B and T cells elicited by a specific pathogen or antigen that can also react to other pathogens or antigens (1) Cross-reactivity is a main feature of adaptive immunity, which is highly favored by the recognition of small portions within protein antigens (epitopes) (2) and the poly-specificity of cognate B and T cell receptors (3, 4). Human common cold coronaviruses (hCoVs) have received major attention as potential sources of cross-reactive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 (5). However, immune cross-reactivity has also been reported between SARS-CoV-2 and unrelated viruses (6), bacteria (7), vaccines (8, 9) and even food antigens (9). Activation of cross-reactive immunity is not always protective and can also produce immunopathology (10). Moreover, immune cross-reactivity is a two-way road and SARS-CoV-2 infection as well as COVID-19 vaccines can also induce cross-reactive immunity. Indeed, immune cross-reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 vaccines with human tissues has been shown, raising the possibility that autoimmune reactivity can result from SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccines (see Figure 1) (11).”

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1509379/full

What can be taken from the evidence presented over the course of the “pandemic” is that the so-called “specific antibodies” to “SARS-CoV-2” are not specific at all. In fact, according to their own studies, these proteins have been shown to bind to a wide range of substances, including, but most likely not limited to:

“Viruses:” Other “coronaviruses,” Herpes, Influenza, Human “papillomavirus” (HPV), Respiratory syncytial “virus” (RSV), “Rhinoviruses,” “Adenoviruses,” “Poliovirus,” Mumps, Measles, Ebola, “HIV,” Epstein-Barr “virus,” “Cytomegalovirus” (CMV)

Bacteria: Pneumococcal bacteria, E. faecalis, E. coli, Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacterium associated with Lyme disease)

Parasites: Plasmodium species (Malaria), Schistosomes

Vaccines: DTaP, BCG, MMR

Foods: Milk, Peas, Soybeans, Lentils, Wheat, Roasted almonds, Cashews, Peanuts, Broccoli, Pork, Rice, Pineapple

The lack of specificity of “antibodies” and the unreliability of “antibody” tests is a well-documented issue in the mainstream literature. The “really terrible accuracy” of “antibody” tests was discussed as early as April 2020. In May 2020, “experts” acknowledged that “antibody” tests “may not mean much at all” due to “too many unknowns, both about the accuracy of the antibody tests that are available and about the nature of the virus itself.” In May 2021, the FDA explicitly warned the public not to use authorized “SARS-CoV-2 antibody” tests to evaluate a person’s level of “immunity” or “protection” from “Covid” at any time, “especially after the person received a COVID-19 vaccination.” The agency stated that “more research is needed to understand the meaning of a positive or negative antibody test, beyond the presence or absence of antibodies.” As recently as September 2024, the CDC reaffirmed that “antibody” testing is “not currently recommended to assess a person's protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe COVID-19 following COVID-19 vaccination or prior infection, or to assess the need for vaccination in an unvaccinated person.”

This highlights a critical issue: the concept of “specific antibodies” for “SARS-CoV-2” is misleading. Given their documented cross-reactivity with numerous other substances, these so-called “antibodies” cannot be considered truly specific to the “virus.” This undermines the assumption that a positive result from an “antibody-based” assay conclusively identifies a unique “pathogen” rather than a structurally similar but unrelated protein. As a result, “antibody” tests cannot definitively confirm exposure to “SARS-COV-2” or any other “virus.” At best, a positive result may simply reflect past exposure to unrelated factors that triggered a similar response measured by fraudulent tests. Since no truly specific “antibodies” exist, “antibody-based” testing and claims of “immunity” based on these tests are fundamentally flawed. Therefore, these tests lack scientific reliability and cannot be trusted for individual diagnosis, research purposes, or public health policy. Given the inevitability of cross-reactivity and false results, these unreliable tests should never be used to “confirm” past “infection,” detect the presence of a supposed “virus,” or to establish so-called “immunity” from vaccination.

provided a fascinating examination of the history of John Kellogg, “germs,” and the food pyramids. produced a list of 24 censored documentaries that expose the medical fraud of vaccines. showed that the Scottish Government has no scientific evidence of any bird flu “virus.” pointed out that HIV fearmongering is making a way back into the headlines. questioned the traditional beliefs about “virus isolation.” and shared 10 reasons not to get vaccinated.

Had to read this excellent article from Mr. Stone twice because it is packed with information on a complex topic. Most of his articles require multiple readings as they deal with difficult subjects and he puts a lot of material into them. He cites the actual research papers by the authoritative institutions and supplements them with his more layman friendly synopses of these scientific works to facilitate comprehension. There is a lot of work and thought going into these analyses. Thank you for your efforts to enlighten your fellow man to the con game called virology Mr. Stone. As for this particular topic of antibodies and their role in the fairy tale of virology, he shows how weak is their applications, filled with speculation, contradictions, caveats, circular reasoning etc. so that it is astounding to believe they are thought to be supporting scientific conclusions. More hogwash by a compromised profession.

The corona antibodies mostly cross-react with green ink.