ViroLIEgy 101: Logical Fallacies

The flawed reasoning ingrained within the foundations of virology has infected the minds of those who consider themselves rational thinkers.

ViroLIEgy 101 is a series of articles meant to provide relatively short (by my standards) and concise explanations of key concepts regarding both germ “theory” and virology. I’m providing an overview on topics that are essential to the conversation that people may be confused with and have difficulty understanding, or areas that seem to be controversial when engaging in discussions with those defending the germ “theory” of disease.

The field of virology is considered a cornerstone of modern medicine, and the widespread acceptance of “viruses” as causal factors in disease is driving the rise of a powerful pharmaceutical industry, one that has profitted greatly from the production of countless vaccines and various medications to combat these invisible “pathogenic” entities. Despite employing every available method to control these outbreaks, the incidences of emerging and re-emerging “viral” diseases are continually increasing every year. Many excuses have been given as to why these “protective” measures are failing to combat and reduce “infectious” disease including globalization, urbanization, environmental changes, population growth, socioeconomic factors, “antiviral” resistance (i.e. medication failure), and my personal favorite, “viral mutation and evolution.” While it should be evident that injecting and consuming toxic substances to fight fictional entities cannot lead to lasting health, there is a deeper reason for why these measures continue to fail. Beneath the surface of its seemingly rigorous methodologies, virology rests on a foundation built upon flawed logic. At the core of virological research lies the assumption of an invisible pathogenic entity, with the “gold standard” cell culture experiment frequently portrayed as conclusive evidence of “viral” existence and pathogenicity. Yet, when one examines the methods closely, this experiment at the very heart of the field is fraught with logical fallacies that permeate deep into the core of virology—namely begging the question, affirming the consequent, and the false cause fallacy.

Interestingly, I have found that when confronting defenders of virology with criticisms of the field's inherently fallacious logic, they often resort to the same flawed reasoning embedded within its foundational experiments. This creates an inadvertent perpetuation of the very fallacies that undermine both the field and their position, resulting in a cyclical pattern of flawed reasoning. When the defenders of virology engage in this kind of circular reasoning, they are failing to address the fundamental flaws within the methodology while reinforcing the shaky foundation upon which the entire field rests. In other words, their defense of virology is constructed with the same logical errors that plague the experimental methods used by virologists, thus making any attempt to justify the field's conclusions inherently flawed.

Frustratingly, those who defend virology often appear oblivious to their engagement in logically fallacious reasoning. This may stem from an educational system that prioritizes memorization and obedience over critical thinking and logic, or perhaps from a lifetime of indoctrination into a flawed paradigm of disease and healthcare. Whatever the cause, many seem confused about what logical fallacies are and how the flawed reasoning infiltrates their thinking and argumentation. In order to help clear up this confusion, this article will explore the nature of logical fallacies and their relevance to virology. While it is beyond the scope of this article to address every fallacy, the focus will be on the three aforementioned fallacies that are deeply embedded within the very fabric of virology and its methodology. To illustrate how deeply ingrained flawed reasoning can negatively impact those who pride themselves on logical thinking, we will examine a recent example that demonstrates how easily defenders of virology can fall into the logical fallacies inherent within a field built upon such errors.

What are Logical Fallacies?

Logical fallacies are common, everyday errors in reasoning or judgment. We all fall victim to this type of flawed reasoning on a regular basis, and there are many ways in which it can occur. These fallacies are illusions of rational thought that can trick both parties into believing a valid point is being made when it is not. When fallacies are used in a debate intended to establish a rational position, they severely undermine the logic of the argument. This is because fallacies, whether intentional or not, often manifest as illegitimate arguments or irrelevant points that lack critical evidence to support the claims being made. Therefore, it is crucial to be aware of the various ways in which we might engage in these errors to avoid falling prey to illogical thinking and irrational arguments.

In virology, the very foundational premises of the entire field are steeped in logically fallacious thinking, and these errors are infused within both the experiments and the interpretations of their results. Like the imaginary “viruses” that are supposed to be detected, this flawed reasoning spreads from one person to another, whether they are conducting research or defending the field from criticism. To stamp out this fallacy “virus” that has “infected” the minds of those who might otherwise think rationally, let's examine what I consider to be the three core fallacies that hold together this pseudoscientific discipline in order to gain a clearer perspective.

Begging the Question

The begging the question fallacy is fundamental to the problems relating to virology. In short, this fallacy occurs when “the argument's premises assume the truth of the conclusion, instead of supporting it. In other words, you assume without proof the stand/position, or a significant part of the stand, that is in question.” Regarding virology, researchers assume the existence of a pathogenic “virus,” and they then attribute certain phenomena to the invisible entity as proof that it exists. This results in circular reasoning that fails to provide independent evidence for the entity's existence; instead, it presupposes the very thing it aims to establish.

This is the core flaw in virology as a scientific discipline. The very entity assumed as the cause of an effect is never directly proven to exist before any experiments aimed at determining causality are conducted. It is essential and imperative that the cause (the assumed “viral” particles) is shown to exist before the effect. This principle, known as time order, is the first of four necessary conditions that must be met in order to demonstrate a causal relationship between two variables.

To establish a causal relationship between two variables, you must establish that four conditions exist:

1) time order: the cause must exist before the effect;

2) co-variation: a change in the cause produces a change in the effect;

3) rationale: there must be a reasonable explanation of why they are related;

4) non-spuriousness: no other (rival) cause for the effect can be found.

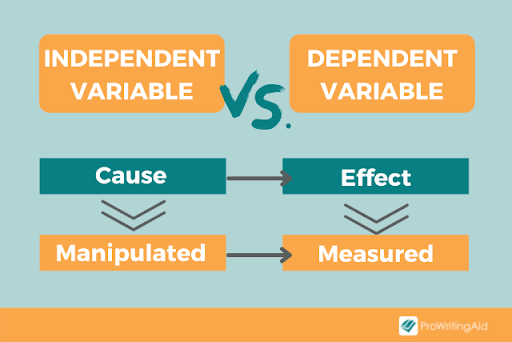

A central goal of scientific research is to demonstrate that the independent variable (the presumed cause) influences the dependent variable (the observed effect). To test any hypothesis suggesting a causal relationship, the independent variable must be present from the start of the experiment. It must be varied and manipulated during the experiment in order to observe its impact on the dependent variable. This sequence is not just a procedural necessity but a demand of logic.

“In order for the independent variable to cause the dependent variable, logic dictates that the independent variable must occur first in time; in short, the cause must come before the effect.”

The core issue for virology is that the field has an independent variable problem, as the "virus" has never been directly observed in nature. The “virus” concept was conceived of in the late 1800s to account for the inability to fulfill Koch's Postulates in every case of disease. Subsequent experiments that assumed the presence of the "virus" and attributed effects to this unobservable entity began by begging the question of its existence, along with the effects it purportedly causes. In other words, the phenomena created in labs were attributed to the presence of the “virus” through a fallacious cycle of circular reasoning—one that virology has yet to break free from.

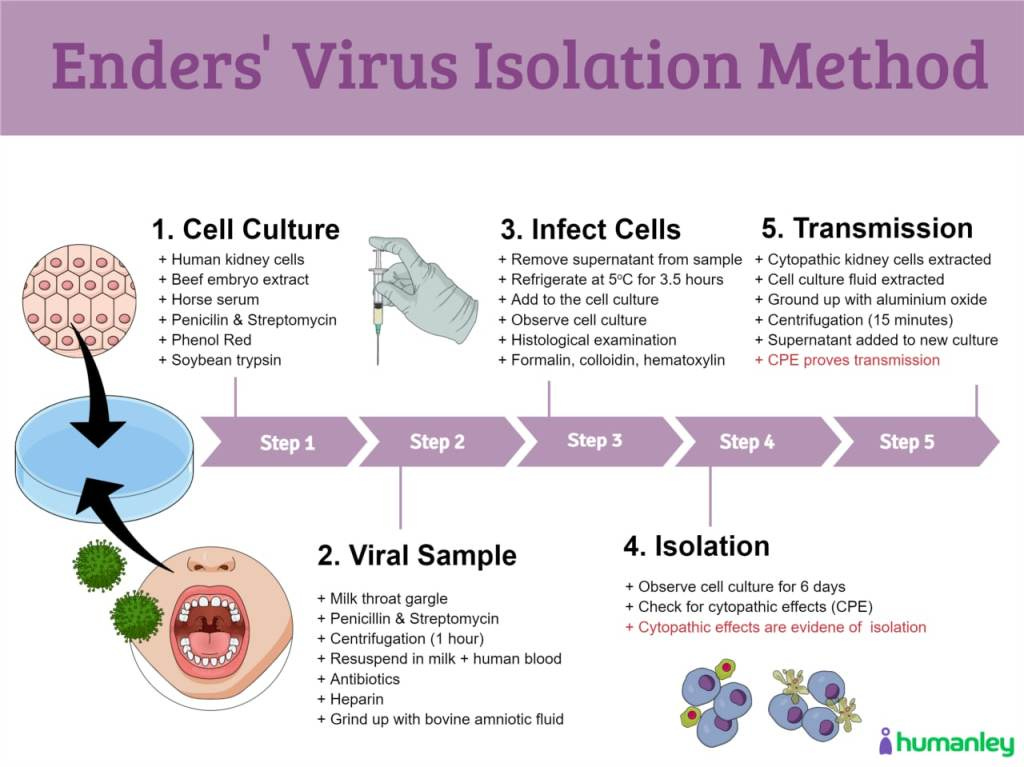

For over 60 years, virologists struggled to convincingly demonstrate that they were working with actual pathogenic “viruses” in their experiments. In fact, there wasn't even consensus on what a “virus” was until 1957. However, in 1954, virologist John Franklin Enders, while supposedly working with the measles “virus,” introduced an illogical experimental setup that allowed researchers to claim that they were working with the entities that they believed were present in the fluids of sick patients. This was the cell culture experiment, which began with the assumption that the unseen “viruses” were already present within a sick patient's fluids. When these fluids were added to a Petri dish containing kidney cells from African green monkeys, along with various chemicals and foreign additives, Enders observed what he referred to as the cytopathogenic effect (CPE). This effect was then attributed to “viruses” and used as evidence that these invisible entities are present within the sample, thus completing the illogical circular loop where the effect was taken as proof of the cause. This experimental method was fundamentally flawed, as it was based on the fallacy of begging the question. This basic illogical premise is ingrained in all virology research that has proceeded afterwards.

Affirming the Consequent

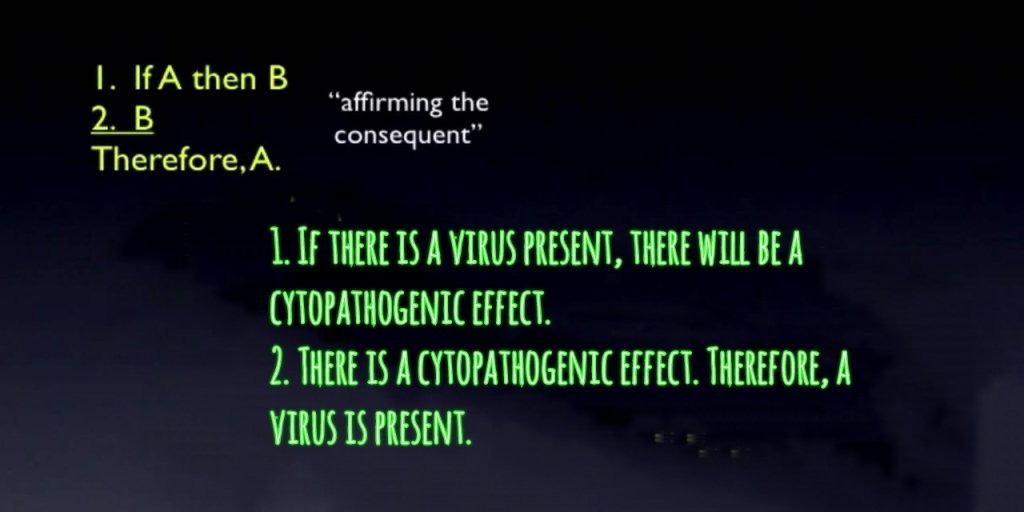

A second fallacy embedded in the methods of virology is known as affirming the consequent. This fallacy involves the use of a conditional statement, typically written as an “if-then” sentence, which expresses a link between the antecedent (the part after the “if”) and the consequent (the part after the “then”). It's important to note that conditional statements do not assert the truth of either the antecedent or the consequent—they only claim that if the antecedent is true, then the consequent must also be true. To commit this fallacy, one would mistakenly claim that the presence of the consequent confirms the truth of the antecedent. This fallacy can be expressed as follows:

If A, then B.

B.

Therefore, A.

An easy example of an affirming the consequent fallacy would look something like this:

If I eat 25 apples at once, I will get a stomachache.

I have a stomachache.

Therefore, I ate 25 apples at once.

This reasoning is obviously fallacious because there could be many reasons for having a stomachache that do not involve eating 25 apples at once. A stomachache is not proof that someone ate 25 apples. Here’s another simple example:

If it rained outside, the street will be wet.

The street is wet.

Therefore, it rained outside.

Once again, this reasoning is fallacious because the street could be wet for reasons that don’t involve rain. Someone could have sprayed a hose, a fire hydrant might have burst, or a street cleaner could have passed through the neighborhood. Just because the street is wet doesn’t automatically mean it rained. Therefore, the conclusion does not confirm the truth of the premise, making the reasoning fallacious.

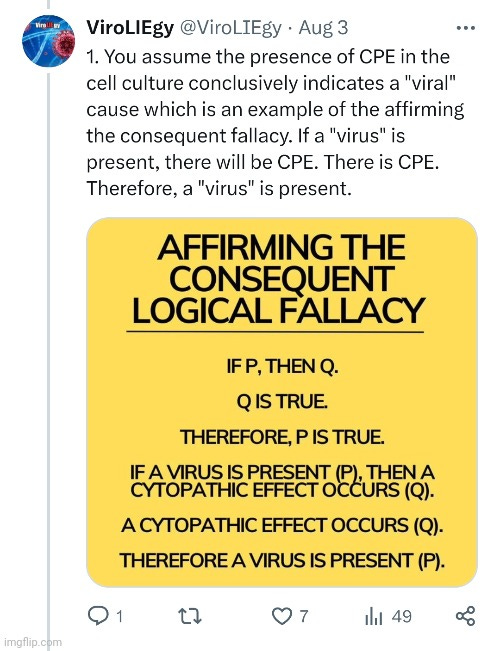

In the cell culture experiment, this fallacy is carried out in a similar fashion. Virologists assume that the observation of CPE in their “infected” cultures is evidence that a “virus” is present.

If a “virus” is present in the sample, there will be CPE in the culture.

There is CPE.

Therefore, there is a “virus” present in the sample.

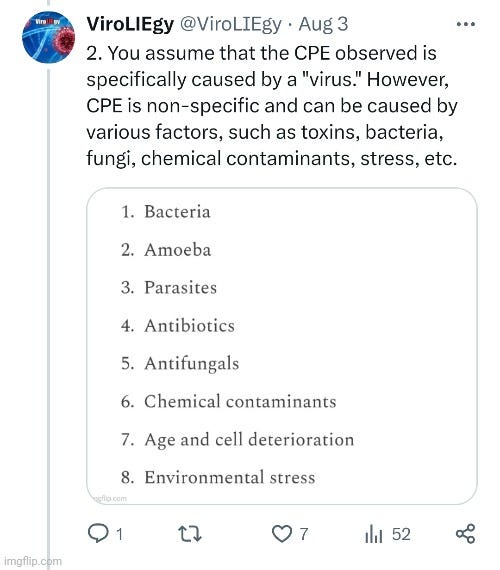

This is fallacious for several reasons, the most important being that there must be proof of the “virus’s” existence before observing CPE. The effect (the consequent) cannot be used to claim the existence of the cause (the antecedent). As with the other examples provided, there are many potential reasons why virologists might observe CPE in their “infected” cultures, which we will explore next.

False Cause

The false cause fallacy occurs when someone incorrectly assumes, without proof, that a causal relationship exists between two variables or events. Anytime someone claims that “A causes B” without sufficient reason and evidence to believe that B is truly caused by A, this fallacy is in play. This flawed reasoning is often summed up by the phrase, “correlation does not equal causation.” Just because one event follows another, or even if events occur simultaneously, does not mean that they are causally related. Here are some excellent examples of this fallacy in action:

We never had a problem with this elevator until you moved into the building.

They had a very successful business. Then they decided to adopt a child, and the business went immediately into the red.

Please read this message then forward it. Three people who received and forwarded this message received thousands of dollars each, but Ms. Elma Smith failed to forward this message and she suffered a lengthy problem with an ingrown toenail. Forward this to five people right away, if you know what is good for you.

When the NFC wins the Super Bowl, the Stock Market usually has a good year. I hope the NFC wins next year because my portfolio is taking a beating.

I'm sure that Marilyn Manson's music had something to do with those murders. They found Manson CD's in one of the murderer's private collection.

In these cases, people are assuming a connection between two events simply because they occurred one after the other or closely together in time. This same flawed reasoning is evident in the cell culture experiments performed by virologists. They assume that adding unpurified lung fluid or nasal mucus from a sick patient to a culture of monkey kidney cells, followed by the observation of CPE, implies that a “virus” was present in the sample and ultimately caused the CPE. This reasoning ties back to the fallacy of begging the question regarding the existence of the “virus” in the first place, as well as affirming the consequent by using the effect (CPE) as proof of the supposed cause (the “virus”). It's a tangled web of circular reasoning, with no direct proof of any entity described as a pathogenic “virus” before any experiments or observations take place.

This fallacy was utilized by John Franklin Enders in his original 1954 paper establishing the cell culture experiment when he assumed that the CPE that occurred in his “infected” cultures was evidence that he has “isolated” the cause of the effect in the measles “virus.”

B ) Cytopathogenic range. Monkey kidney is the only other tissue employed that has yielded a growth of cells in which the characteristic changes described above have been definitely observed following inoculation of virus. In cultures consisting largely of monkey renal epithelial cells as prepared by Youngner’s modification of Dulbecco’s technic (13) cytopathic changes have been regularly observed which resemble closely those produced by these agents in human renal cells as seen in both fresh and stained preparations. These effects followed the addition of blood or throat washings from cases of measles as well as infected tissue culture fluids derived from previous passages.

Directly after this passage, Enders did concede to other possible causes of the observed CPE. However, he still maintained that the CPE caused by these other “viral” agents or unknown factors resembled the CPE that he was already attributing to a measles “virus.”

Monkey kidney cultures may, therefore, be applied to the study of these agents in the same manner as cultures of human kidney. In so doing, however, it must be borne in mind that cytopathic effects which superficially resemble those resulting from infection by the measles agents may possibly be induced by other viral agents present in the monkey kidney tissue (cf. last paragraph under G) or by unknown factors.

Enders would ultimately conclude that the findings in his paper of the cytopathogenic changes supported his presumption that they are caused by the measles “virus.”

Conclusion. The findings just summarized support the presumption that this group of agents is composed of representatives of the viral species responsible for measles.

Why Enders would initially believe that the cytopathogenic changes observed in tissue and cell cultures were caused by a “measles virus” is puzzling, especially given his own acknowledgments in a paper titled Cytopathology of Virus Infections: Particular Reference to Tissue Culture Studies, published the same year as his measles paper. In this work, Enders made some revealing concessions regarding the interpretation of CPE. He explained that CPE can be triggered by many harmful agents, and that, on its own, this observation could not be conclusively attributed to “viral” activity. Despite this, Enders asserted that an observer familiar with the specific CPE patterns attributed to a particular “virus” might tentatively conclude that a “virus” is responsible.

“The phenomena mentioned above under Group 1 changes may be evoked by many noxious agents. Accordingly, they cannot alone be considered as necessarily the result of viral activity. To prove this certain control procedures (serial cultivation, prevention of changes by homologous antibody, etc.) must be applied. Familiarity, however, with the effects of a specific virus in a given cell system often enables the observer to conclude tentatively that this virus is responsible.”

Enders also discussed morphological changes such as inclusion bodies, which were considered characteristic of “viral infection.” However, he conceded that these changes were not definitive evidence of “viral” activity, as certain chemicals and unknown factors could also produce such changes. Inclusion bodies were among the earliest changes attributed to “viruses” and were used as criteria for “infection,” even though other factors could result in their appearance.

“Of morphological indices of viral injury, the formation of inclusion bodies (Group 2 above) is the most characteristic, although again this process cannot be accepted as conclusive evidence of viral activity since certain chemical as well as other unknown factors may condition its development. Inclusion bodies were the first cytopathic changes to be sought for in vitro and employed as criteria of infection. As indices of viral multiplication, however, they are less useful than the changes of Group 1, because these structures can be unmistakably demonstrated only in stained preparations.”

Enders conceded that cytopathogenic changes observed in the lab are influenced by numerous factors—some known, while others remain undefined. He attempted to correlate certain susceptible cell lines with “viral replication,” but he noted that this correlation did not always hold true, and that the opposite was sometimes observed:

Cytopathogenicity in vitro is influenced by factors some of which are known while many remain to be defined. At the outset a few of those now recognized will be mentioned as an introduction to the review of recorded observations on the behavior of individual agents. Of primary importance is the species from which the cells are derived. Analogous to the host range of a virus is its cytopathogenic range in cultivated cells. But correlation between susceptibility of the organism and its cells in vivo does not always exist. For although this correlation frequently obtains, the tissues of a susceptible species occasionally fail to support viral multiplication while the converse of this situation also occurs.

Enders tried to argue that certain “viruses” specifically target certain cell types, but he also admitted that there is no absolute relationship between cytotropism in vivo and in vitro:

Cell type is, with certain viruses, a determining factor. Thus an agent may attack and destroy epithelial cells present in a culture leaving fibroblasts intact. Experiments with strains consisting of a single cell type have been few, but the results indicate that the cytotropic properties of viruses in vivo may be retained in vitro. Once more, however, there is no absolute relationship between cytotropism in vivo and in vitro.

He further noted that the age of the donor tissue can influence cytopathogenicity:

The age of the donor of tissue may influence cytopathogenicity. Just as young animals are frequently more susceptible to infection so their tissues may be more vulnerable to injury by the virus, yet again this correlation is not invariable. Most of the pertinent data indicate that acquired immunity to viral infections is not reflected by an increased cellular resistance, a fact advantageous from the technical point of view since it eliminates concern over the immunologic status of the donor animal.

Moreover, Enders admitted that the conditions under which the assumed “virus” has been propagated prior to its study in tissue culture can influence the intensity and degree of CPE. He acknowledged that serial passaging might enhance moderate or weak cytopathogenicity, showing that the researcher's approach can directly influence the observation of CPE:

The intensity and degree of cytopathic injury may vary according to the strain of virus or the conditions under which it has been propagated prior to its study in tissue culture. The investigator should be prepared to encounter such variations in the study of a number of representatives of a viral species. Moderate or weak cytopathogenicity may sometimes be enhanced by serial passage in vitro.

Finally, Enders recognized that environmental factors—both known and unknown—within the culture can also enhance or suppress cytopathogenic activity. He pointed to the composition of the medium, the temperature of incubation, and the period of cultivation of the cells before the addition of any “virus” as factors that influence CPE:

Environmental factors in the culture may tend to enhance or suppress cytopathogenic activity. Of these many have not yet been defined, but there is evidence that composition of the medium, temperature of incubation, and period of cultivation of the cells before addition of virus may all be determinants.

Thus, it is evident that John Franklin Enders was aware of various factors unrelated to the presence of any “virus” that could cause the cytopathogenic effect he attributed to the “virus.” Given that he had no direct evidence pertaining to the existence of, and actually working with, a pathogenic “virus” (begging the question) and that he used an observed effect to assert the existence of its cause (affirming the consequent), it becomes clear that Enders committed a false cause fallacy. There were multiple known factors capable of producing the same effect, making the explanation of a “virus” unnecessary and entirely illogical.

Empowering Logical Fallacies with Jeremy Hammond

The three fallacies discussed above represent what I consider to be the fundamental logical errors deeply embedded within the foundation of virology. Understanding these fallacies equips you to critically analyze the pseudoscientific literature in related fields like immunology, epidemiology, genomics, and beyond. While there are certainly more fallacies utilized within these disciplines that contribute to the illogical arguments of their defenders, my aim is to highlight how these core fallacies are employed by those who claim to value rational thought. To illustrate this, I am presenting excerpts from a recent exchange with “health freedom” activist Jeremy Hammond, who seemingly takes pride in his logical reasoning.

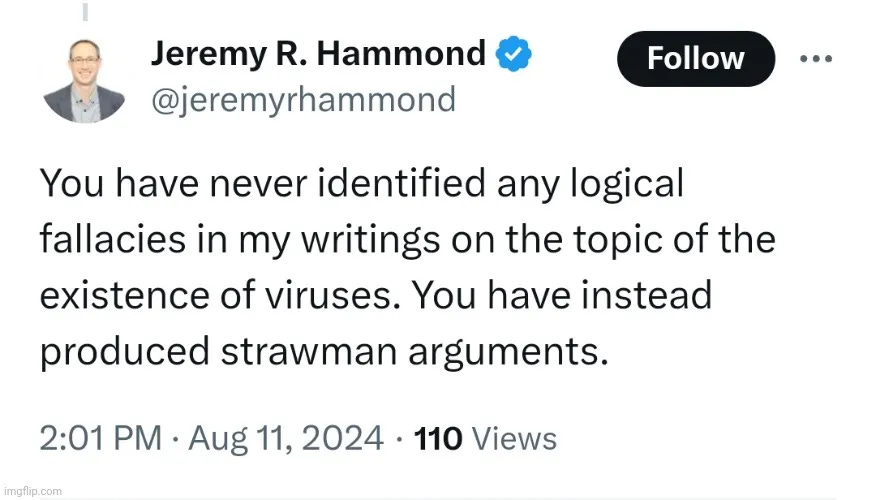

For those who may be unfamiliar, Jeremy considers himself a “truly independent journalist” and an author who “exposes dangerous state propaganda serving to manufacture consent for criminal government policies.” He has become a voice in the “anti-vaccine” crowd and has produced many articles about the dangers involved in this practice. Robert Kennedy Jr., the supposed “anti-vaccine” candidate for President of the United States, has stated that “Jeremy Hammond is a brilliant and accomplished journalist.” In conversation, Jeremy regularly calls out those whom he thinks are engaging in logically fallacious reasoning, and he openly challenges anyone to find any logical fallacies in his writings.

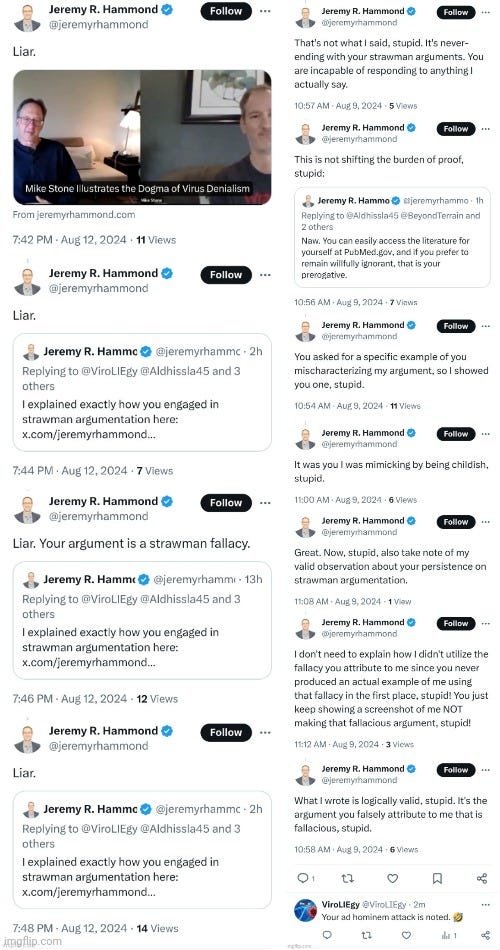

Thus, one would think that Jeremy would have a fairly solid grasp on what constitutes logically fallacious reasoning, especially when examining the field of virology. However, I have first-hand experience in my own conversations with Jeremy that demonstrate that this is not the case. As I do not find interacting with Jeremy Hammond particularly pleasant (see the below examples where I am constantly referred to as “stupid,” “liar,” and my personal favorite, “doofus”), I do not go out of my way to engage in discussions with him very often.

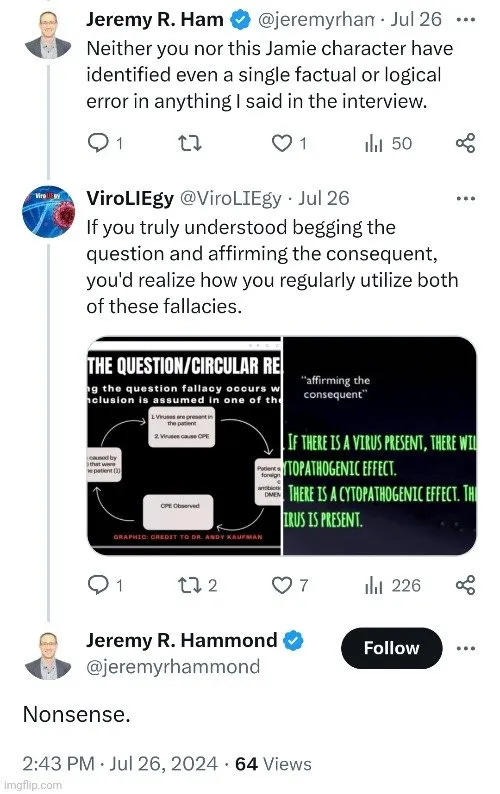

However, after Jeremy participated in a recent interview on the Beyond Terrain podcast where he claimed that he had “addressed false claims made by people who argue that viruses do not exist,” I couldn't help but point out his logically fallacious reasoning, especially when he graciously challenged us to do so.

What followed has been a prolonged exchange marked by numerous fallacious responses on Jeremy's part. While I won’t delve into every detail, as this has unfolded across too many threads to recount in its entirety (a few can be found here and here), Jeremy's persistent confusion and his refusal to acknowledge his flawed reasoning provides a valuable case study. It will show how the flawed reasoning inherent within the field of virology was transferred into someone who presents himself as a logical thinker. This is an excellent example of how the inherent fallacies within the foundation of virology lead its defenders into illogical arguments.

My first attempt to point out Jeremy's fallacious reasoning was by highlighting his error in identifying the proper independent variable (IV)—which is the cause in a proposed cause-and-effect relationship—in the cell culture experiment. Setting aside the fact that the cell culture experiment is pseudoscientific and does not test any hypothesis derived from an observed natural phenomenon in accordance with the scientific method, if it were legitimate, the IV would need to be the specific “viral” particles assumed to cause the dependent variable (DV), the cytopathogenic effect (CPE). Jeremy has consistently misunderstood this point, repeatedly asserting that the unpurified inoculant—containing more than just the assumed “virus,” a fact he previously acknowledged by noting that particles of the same dimension may remain—is the independent variable in the experiment.

Why doesn't Jeremy know exactly what's contained within the sample? Because virologists do not verify whether the assumed “viral” particles actually exist in the fluids of a sick patient before any experimentation begins. Instead, the presence of these “viral” particles is assumed from the start and is then “confirmed” based on the observation of CPE at the end of the experiment. This is why Jeremy claims that the purpose of the cell culture experiment is to find out whether “viruses” are present within a sample.

Remember that to meet the time-order condition—a crucial first step in establishing a cause-and-effect relationship—the cause (the assumed “viral” particles) must exist before the experiment begins. Their presence cannot be determined as a result of the experiment itself. Therefore, when Jeremy claims that the entire purpose of the cell culture experiment is to determine whether a “virus” is present in a sample, he is implicitly engaging in all three core fallacies.

First, he begs the question by assuming (despite his denial) that there could be a pathogenic “virus” existing within the sample from the outset. The experiment assumes the existence of the “virus” to prove its presence. The argument is circular in that it is assuming what it is trying to prove.

Next, he affirms the consequent by implying that the observation of CPE, which is what the experiment is looking for, serves as evidence for the presence of the “virus.” There is the built-in assumptiom that because the cell culture shows CPE, a “virus” must be present. This reasoning assumes a single cause for the observed effect, ignoring other potential explanations.

Finally, he commits a false cause fallacy by implying that the experimental effect is due to the presence of a “virus,” despite the fact that there are numerous potential causes of CPE that do not require the involvement of an unproven “viral” cause. This mistakenly identifies a cause based solely on correlation without properly establishing causality.

Of course, Jeremy did not seem to understand his fallacious reasoning, and he denied that he had engaged in any such fallacies.

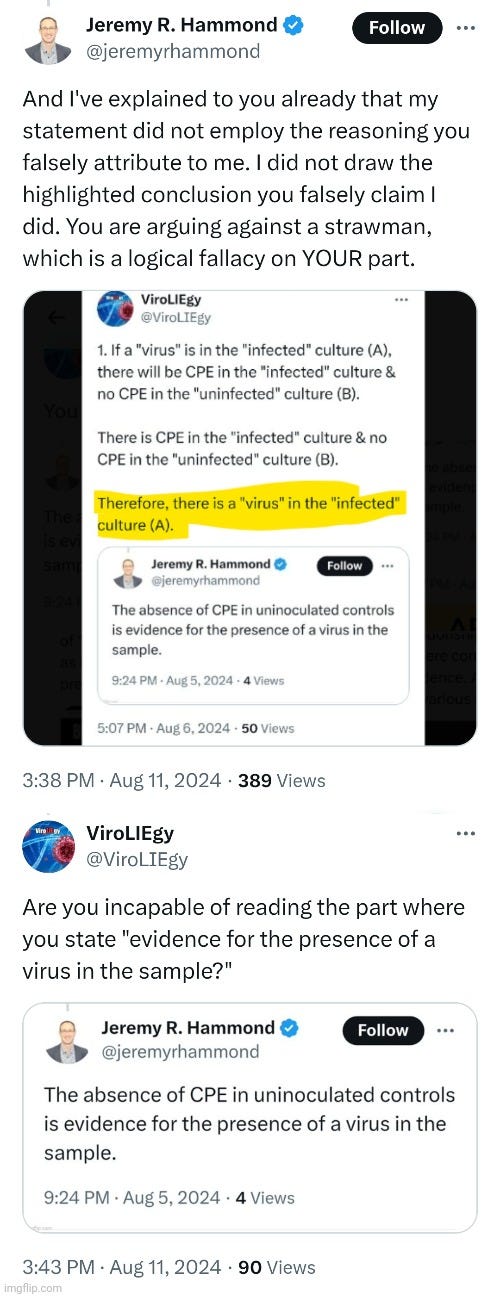

If there was any doubt as to what Jeremy was implying with his statement on the purpose of the cell culture experiment and the fallacies present within, his next response effectively removed it.

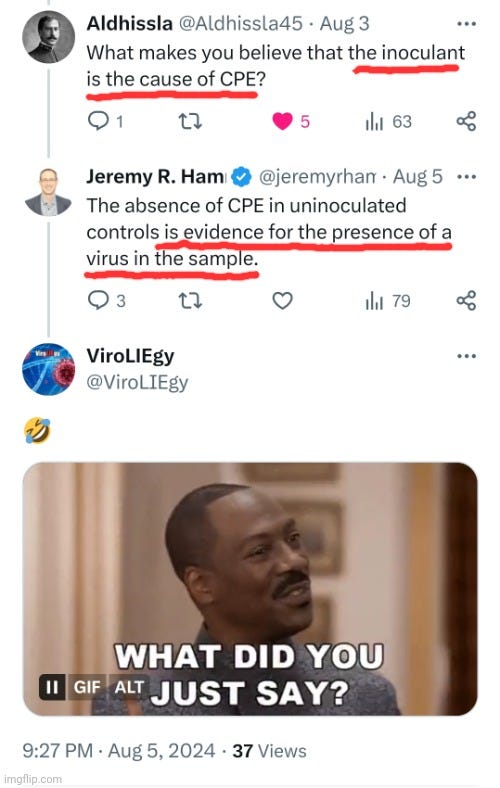

While defending his claim that he did not implicitly commit these fallacies, Jeremy once again committed all three by assuming a “viral” cause and attributing the CPE to it in order to claim the existence of the “virus” itself. By implying that because CPE is observed in the inoculated cultures (and not in the uninoculated controls), the “virus” must be present, he effectively ignored alternative explanations for the phenomenon. His response jumped to the conclusion that the “virus” is “always and ever” the cause of the CPE simply because the CPE occurs after the introduction of the inoculant. This fails to establish a direct causal relationship and disregards other potential factors that could cause the observed effects. Not only did Jeremy commit the core fallacies in question, but he also reinforced his flawed reasoning by demanding an explanation for what else could cause the observed CPE, thereby engaging in a burden of proof reversal fallacy. By asserting that it's impossible to do so while implying that the “virus” is the only possible cause, he doubled down on his logical errors.

This was not the only time that Jeremy locked down his fallacious reasoning. When asked by

what made him believe that the inoculant is the cause of any observed CPE, Jeremy responded by saying that an absence of CPE in an uninoculated control culture is evidence for the presence of a “virus” within the sample.In doing so, Jeremy engaged in begging the question regarding the existence of a pathogenic “virus” within the inoculant while also affirming the consequent by assuming that the presence or absence of CPE in inoculated and uninoculated cultures was evidence of a “viral” presence. By disregarding other potential factors that could explain the CPE, Jeremy further committed a false cause fallacy. This effectively demonstrates that his reasoning is trapped in an illogical, circular loop.

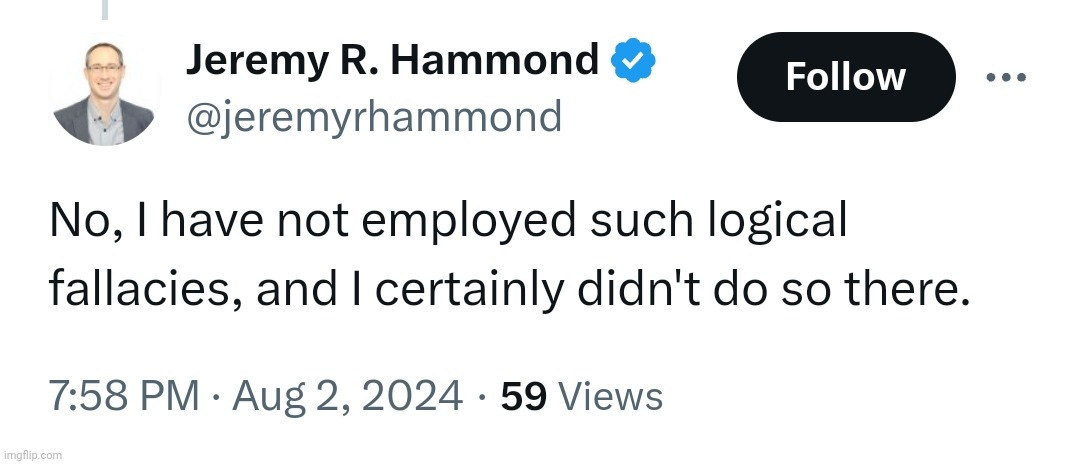

Despite pointing out the core fallacies in his reasoning, Jeremy insisted that I had merely claimed he committed such fallacies without providing specific examples.

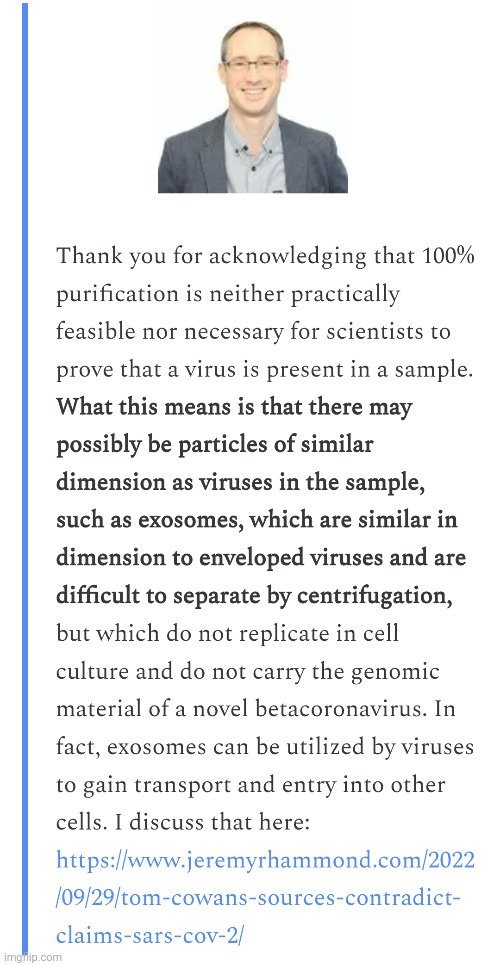

To address this, I provided Jeremy with a direct passage from an article he wrote in response to my article discussing our previous conversation. In the passage, Jeremy clearly stated that, if a “virus” is the cause of a patient's illness, then a sample from the patient should produce CPE when inoculated into a cell culture, as compared to an uninoculated culture.

Jeremy's “if, then…” statement is a textbook example of the affirming the consequent fallacy. He also begs the question by assuming a pathogenic “virus” exists within the patient’s sample and then attributing an observed effect to this unproven entity. Additionally, he commits a false cause fallacy by ignoring other known factors that can lead to CPE. There is no need to jump to a conclusion of a “viral” cause when other plausible explanations have not been ruled out.

Unsuprisingly, when faced with the fallacious reasoning displayed in his article, Jeremy did not own his logical errors.

As he was having difficulty with understanding his fallacious reasoning, I provided Jeremy with a detailed explanation as to how he engaged in the core fallacies.

This was once again met with denial on Jeremy's part.

It became very apparent to me that Jeremy would not acknowledge the core fallacies ingrained in the cell culture experiment or his continued reliance on this flawed reasoning to defend virology. Unable to provide any logical counterarguments to my explanations of his frequent use of flawed logic, Jeremy tried a different tactic. He began accusing me of committing a straw man fallacy by misrepresenting his position. Initially, he attempted to argue that he never concluded that the presence or absence of CPE indicates a “viral” presence in a sample, even though he had clearly made that claim.

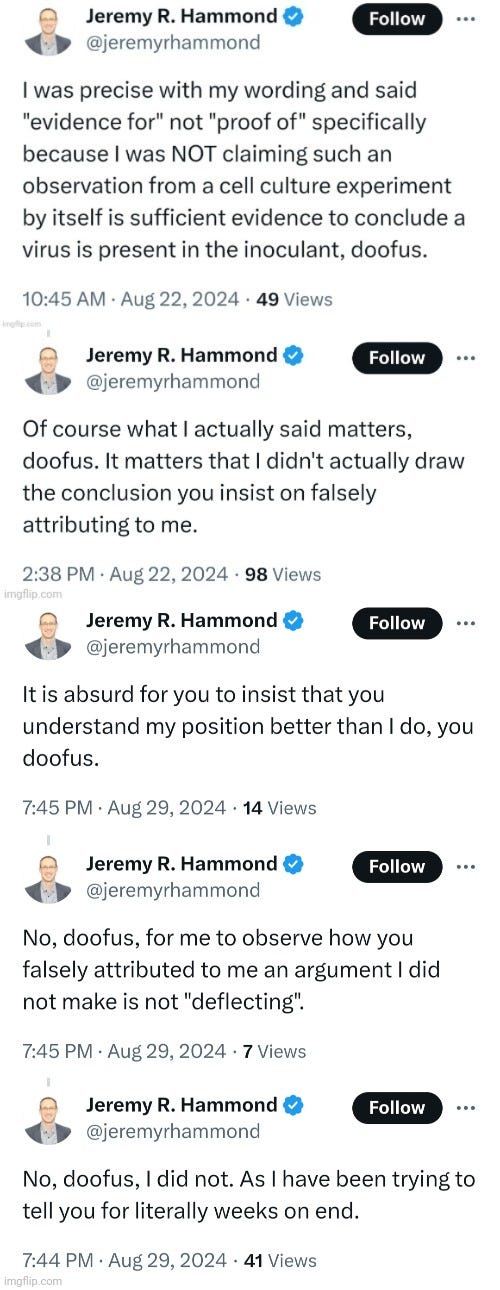

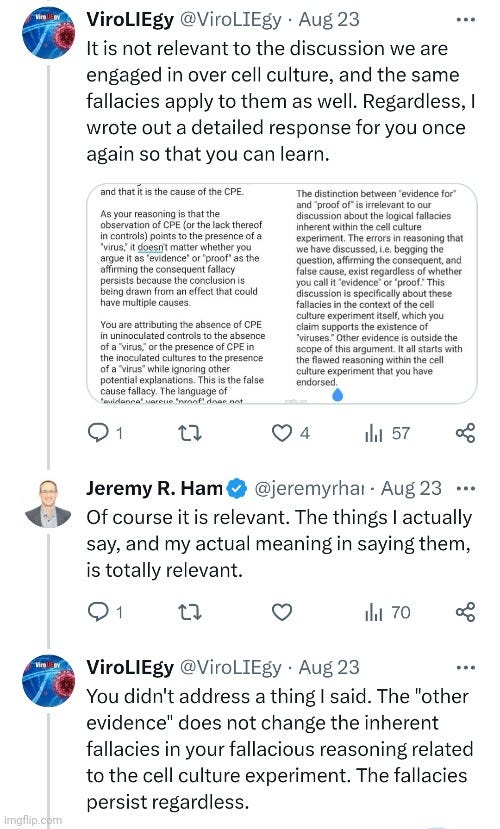

When that tactic failed, Jeremy argued that he never stated that CPE was “sufficient evidence” of a “virus.”

He tried to distinguish between “proof of a virus” and “evidence of a virus” to claim that he was not engaging in fallacious reasoning.

Unfortunately for Jeremy, the core fallacies remain even if he backtracks by saying that CPE is not “sufficient evidence” or “proof of” a “virus,” but rather “evidence for” one. The fallacies also persist despite the presence of additional evidence—whether it be EM images, antibody testing, genomic data, etc.—because all of these forms of evidence rely on the cell culture experiment as their logically flawed foundation. In response, I provided Jeremy with a rather lengthy explanation that exceeded Twitter's character limit, which I am reproducing here:

Whether you say “evidence for” or “proof of,” the begging the question fallacy remains because you are still assuming the existence of the “virus” and that it is the cause of the CPE.

As your reasoning is that the observation of CPE (or the lack thereof in controls) points to the presence of a “virus,” it doesn't matter whether you argue it as “evidence” or “proof” as the affirming the consequent fallacy persists because the conclusion is being drawn from an effect that could have multiple causes.

You are attributing the absence of CPE in uninoculated controls to the absence of a “virus,” or the presence of CPE in the inoculated cultures to the presence of a “virus,” while ignoring other potential explanations. This is the false cause fallacy. The language of “evidence” versus “proof” does not change the fact that you are making an unsupported causal inference.

The distinction between “evidence for” and “proof of” is irrelevant to our discussion about the logical fallacies inherent within the cell culture experiment. The errors in reasoning that we have discussed, i.e. begging the question, affirming the consequent, and false cause, exist regardless of whether you call it “evidence” or “proof.” This discussion is specifically about these fallacies in the context of the cell culture experiment itself, which you claim supports the existence of “viruses.” Other evidence is outside the scope of this argument. It all starts with the flawed reasoning within the cell culture experiment that you have endorsed.

Regarding the “other evidence,” I broke down for Jeremy why these same core fallacies persist regardless of a combined effort to produce “sufficient evidence.”

Evidence like EM, antibody tests, and sequencing still relies upon initial cell culture steps where “viruses” are assumed to be present without independent verification outside of these circular arguments. Thus, the begging the question fallacy remains regardless of these forms of evidence.

Even if EM, antibody tests, and sequencing provide additional evidence, these methods also start with “viruses” being assumed to exist in a sample prepared via the cell culture. This evidence is interpreted under the assumption that the “virus” is the cause of observed phenomena, which is the same circular logic fallacy displayed in affirming the consequent.

The presence of other evidence such as EM or genomic data does not necessarily rule out other potential causes of CPE. Each method still depends upon the assumption that the “virus,” which is claimed to be “isolated” and amplified via the cell culture, is the sole cause of these effects. Thus, the false cause fallacy remains despite your use of “other evidence.”

The use of additional forms of evidence like EM, antibody testing, and genomic sequencing do not independently verify the existence of a “virus” outside the context of the original cell culture experiment where the fallacies discussed were engaged. The evidence from these methods is derived from materials (“viral” particles or genetic material) that are obtained through the initial cell culture experiment. Thus, they still depend upon that primary method where the fallacies were originally engaged.

If you wanted to absolve yourself of the logical fallacies, you would need to provide evidence of the existence of a “virus” and its role in causing CPE that does not rely on assuming the “virus’s” presence in the first place. As long as your argumentation and evidence depends upon the initial cell culture steps involving these assumptions, the logical fallacies still apply.

Unsurprisingly, Jeremy simply ignored the points that I made while reiterating that his words are relevant.

What Jeremy seems content to ignore is that distinguishing between “evidence for” and “proof of” does not absolve him from committing the core fallacies identified. The issue isn’t about whether or not he claims CPE is “sufficient proof.” It’s about the structure of his argument. For example, regarding the affirming the consequent fallacy, the logical error persists because when he claims that the absence of CPE in the uninoculated control is “evidence for” the presence of a “virus” in the inoculant, he is still relying on a circular argument that assumes what it sets out to prove, regardless of his choice of wording.

Jeremy seems unable to understand that his flawed reasoning still begs the question and affirms the consequent because it presupposes the existence of the “virus” to explain the observation of CPE, without independent verification of the “virus” outside of the cell culture experiment. Whether he describes it as “evidence for” or “proof of” does not change the fact that the logical structure of his argument is fundamentally flawed. The fallacies rest on an assumed premise rather than one that has been demonstrated.

If Jeremy were intellectually honest, he would acknowledge the fallacious reasoning that he has fallen victim to in his defense of an illogical and pseudoscientific field. To absolve himself of this flawed circular logic, Jeremy would need to recognize that certain evidence must first demonstrate the existence of a “virus” and its role in causing cytopathic effects without assuming its presence from the outset. This evidence would include:

Purification and Isolation: The assumed “viral” particles must be purified and isolated away from other contaminants (like cell debris, bacteria, host organelles, etc.) directly from the fluids of a sick host, without the use of cell cultures.

Direct Visualization: After purification and isolation, the assumed “viral” particles would need to be directly visualized to determine their size, shape, and structure, ensuring that these particles exist independently of culturing.

Characterization: The purified and isolated “viral” particles would need to be characterized in order to determine their unique properties, such as protein composition.

Controlled Experiments: Experiments would then need to be conducted where these purified and characterized “viral” particles (free from contamination) are introduced to healthy cells in a controlled environment to observe if CPE occurs. Control groups should include cells exposed to purified samples without the “virus” and cells exposed to other potentially causative agents.

Independent Replication: These experiments must be replicated independently with consistent results showing that CPE only occurs in the presence of the purified “virus.”

Pathogenicity and Contagion Experiments: Experiments in humans and animals would need to be conducted to demonstrate pathogenicity and contagion through natural exposure routes (such as aerosolization, inhalation, or direct exposure to the sick) to purified and isolated particles.

Elimination of Other Causes: Studies must be conducted to rule out other possible causes of CPE (such as toxins or chemical agents) to ensure that the “virus” is the sole factor causing the effect.

Only then could the inherent fallacies ingrained in current cell culture experiments begin to be avoided, and the illogical loop broken. However, as Jeremy knows well, this essential evidence does not exist.

Therefore, Jeremy and others who defend virology will continue to engage in a continuous cycle of logically fallacious reasoning. This is precisely why it is critical to understand the core fallacies embedded in the foundation of virology and the pseudoscientific nature of the cell culture experiment. The entire framework of “virus” isolation and identification, as practiced today, relies on assumptions that bypass the necessary steps of independent verification and validation. Without recognizing these flaws, one cannot properly evaluate the evidence or make scientifically sound and rational arguments. If one cannot recognize the flawed reasoning within the position they defend, they are bound to repeat the same errors. This will lead them to continue irrationally defending their mistakes, even when attempting to make a simple argument.

A true scientific approach requires a willingness to question foundational assumptions and to revise beliefs in light of new, more rigorous evidence. It also demands intellectual honesty to acknowledge flawed reasoning and seek corrections. Until this happens, the field of virology will remain trapped in a cycle of confirmation bias and unproven assertions, and those who defend it will be stuck in a pattern of repetitive, illogical, and flawed reasoning.

put out a video that set the record straight on recent allegations of plagiarism.The Baileys also discussed the truth about contagion and how such a concept has never been scientifically established.

In relation to this article on logical fallacies, I want to highlight once again Dr. Mark Bailey's excellent essay Virology's Event Horizon that also explores these themes.

had a busy week with FOI's exposing:Monkeypox.

Avian flu.

Hantavirus.

broke down the monkeypox scam in two recent articles: presented a powerful FOI where the CDC essentially admitted to not being able to properly purify and isolate “viruses” in order to obtain a valid genome. provided a look back at an interview with the late journalist John Lauritsen discussing the dangers of AZT use for HIV/AIDS in the 1990s.

You might have also mentioned the 'Appeal to Authority' fallacy. My personal favorite and germane to the virology 'expert' situation.

The Appeal to Authority fallacy occurs when someone relies solely on the opinion or testimony of an authority figure to support a claim, without providing sufficient evidence or logical reasoning to justify the claim. This fallacy is committed when:

* An authority figure is cited without demonstrating their expertise or relevance to the topic at hand.

* The authority’s opinion is presented as fact, without considering alternative perspectives or evidence.

* The argument relies solely on the authority’s reputation or prestige, rather than logical argumentation.

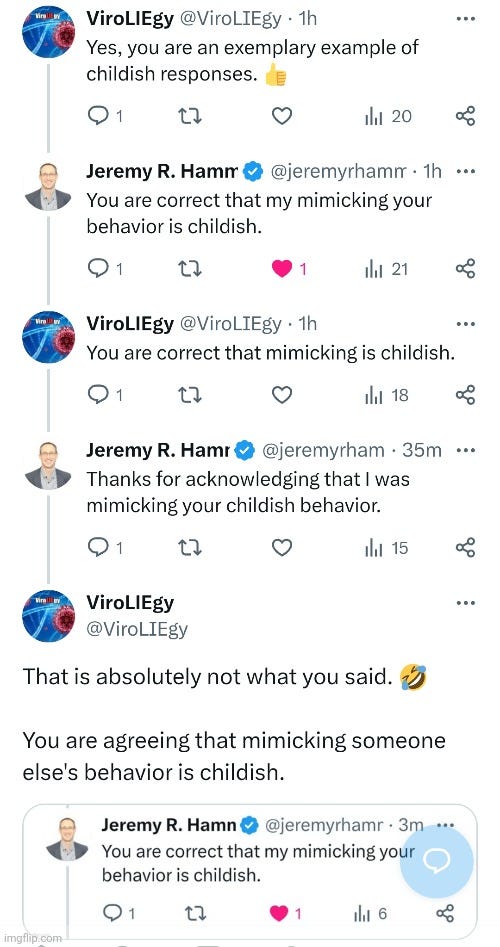

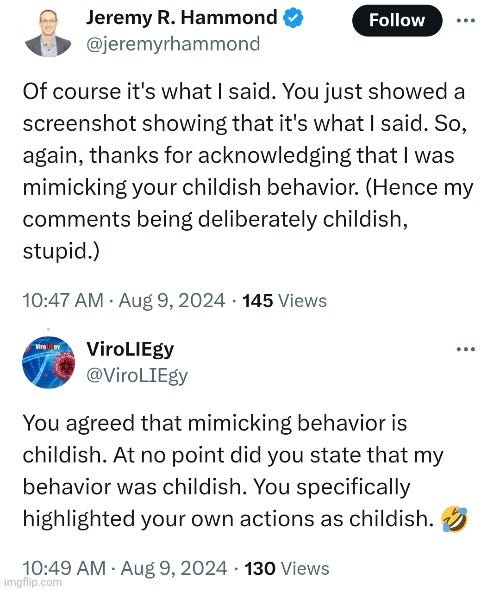

I was thinking Hammond could be aware but unwilling to acknowledge his use of logical fallacies--intellectually dishonest, as you said--until the end, where he appeared to be unable to understand the meaning of his own words! What was he calling "childish?" Not your behavior--but his own! Yet he denied it. Or does he have that poor a grasp of grammar? Can someone really not grasp the meaning of their own words, when reading and re-reading it? Sometimes I wonder about the apparent dumbing-down of so many, maybe all of us to a degree. Education, trauma, vaccine injury, poisons in the food and water, maybe even 5G--it seems that at least some people's brains just don't work very well! Hammond is an example.

And thanks for the detailed exposition of these logical fallacies. It is so important to know about how they work and be able to recognize them literally all around us.