In the late 19th century, scientific medicine underwent a foundational shift—from the belief that miasma, or “bad air,” caused disease—to a germ-centered approach that focused on bacteria as the primary culprits. As bacterial research advanced, efforts to explain “infectious” disease centered on isolating specific microbes believed to cause specific illnesses. This shift began primarily in 1876 with Robert Koch’s work on anthrax, which—while accepted as the first “proven” case of bacterial causation—was still met with both logical and scientific criticism of his methods. Koch’s response to his critics led him to develop new techniques for obtaining pure cultures of bacteria while placing greater emphasis on the experimental demonstration of causation—both of which were missing from his anthrax work.

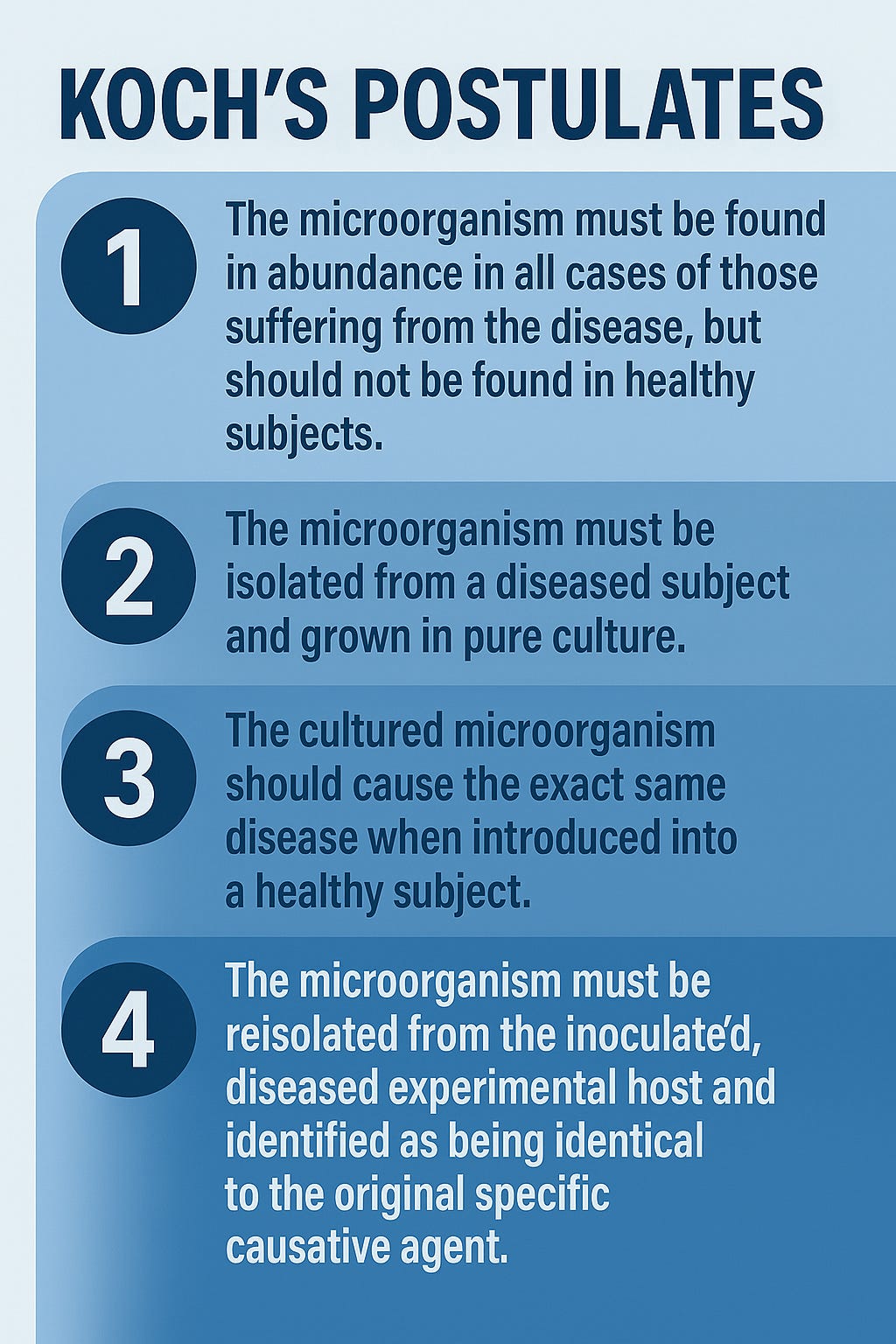

Recognizing the limits of mere association, Koch aimed to strengthen his claims by formalizing a repeatable, logically ordered framework designed to convince skeptics of the germ “theory.” Although he was not the first to propose causation criteria, Koch popularized a systematic approach—later known as Koch’s Postulates—which became the gold standard for establishing the microbiological etiology of disease. His postulates aimed to shift disease theory from speculation to testable, falsifiable hypotheses. For any microbe to be considered the causative agent of a disease, the evidence needed to satisfy all four postulates.

This was intended to ensure that the germ “theory” rested on a secure scientific foundation, not simply mere conjecture.

However, although Koch’s Postulates were widely accepted as the logical framework, it soon became clear that even when pure cultures were obtained, the criteria could not consistently be fulfilled. This failure undermined efforts to definitively prove bacteria as the cause of disease. Even Koch’s own research ran into contradictions: a bacterium might initially appear to fulfill the postulates, only to be later shown to violate one or more of them.

Beyond the difficulty in conclusively proving visible bacteria as causative agents through the fulfillment of the postulates, cases of disease began to emerge that could not be explained by microbes at all. In both human and plant pathology, phenomena were observed that eluded standard microbial detection—cases where no microbe could be found or reliably associated with the disease.

As it became evident that Koch’s Postulates had to be bent or ignored in order to claim that microbes caused disease—and that many diseases had no consistent microbial association—something had to give. When pure cultures failed to meet the criteria, a new theoretical entity was introduced: one that could explain disease without the burden of isolation or visibility. This pivotal shift was acknowledged in Principles of Virology:

“From these beginnings, investigation into the causes of infectious disease was placed on a secure scientific foundation, the first step toward rational treatment and ultimately control. Furthermore, during the last decade of the 19th century, failures of the paradigm that bacterial or fungal agents are responsible for all diseases led to the identification of a new class of infectious agents—submicroscopic pathogens that came to be called viruses.”

Fields Virology similarly admits that it was only when Koch’s Postulates—“an experimental method to be used in all situations”—broke down that the concept of the “virus” arose:

“By the end of the 19th century, these concepts became the dominant paradigm of medical microbiology. They outlined an experimental method to be used in all situations. It was only when these rules broke down and failed to yield a causative agent that the concept of a virus was born.”

These admissions reveal that the concept of the “virus” arose not from scientific success, but from failure—a desperate effort to preserve the causal framework of germ “theory” when its cornerstone could not be fulfilled.

One retrospective account candidly reflected:

“In Pasteur's day, and for many years after his death, the word "virus" was used to describe any cause of infectious disease. Many bacteriologists soon discovered the cause of numerous infections. However, some infections remained, many of them horrendous, for which no bacterial cause could be found. These agents were invisible and could only be grown in living animals. The discovery of viruses was the key that unlocked the door that withheld the secrets of the cause of these mysterious infections. And, although Koch's postulates could not be fulfilled for many of these infections, this did not stop the pioneer virologists from looking for viruses in infections for which no other cause could be found.”

This quote underscores what modern virology often obscures: the “virus” concept was born not from clear, causal demonstration, but as a placeholder for unknown causes due to the inability to satisfy Koch’s Postulates. It was a conceptual sleight of hand—preserving the appearance of scientific rigor while replacing evidence with inference.

With this new theoretical “pathogen”—an unseen, unisolated agent that escaped filters and evaded direct observation—scientists could continue to apply the germ “theory” framework in the face of contradictory evidence and the absence of visible microbes. It provided them with an explanation that maintained the illusion of causal certainty where none had been demonstrated.

This shift in explanation away from the logical framework of Koch’s Postulates gave rise to what would later become the first so-called “virus:” Tobacco Mosaic “Virus” (TMV). This case—though not involving human illness—played a pivotal role in shaping what the medical field came to accept as a “virus:” an invisible, theoretical “pathogen” invoked precisely when bacterial causation failed. As TMV is central to the emergence of the “virus” concept, it's time to examine in depth the key foundational evidence behind the “discovery” of the first “virus” and see whether it holds up under scrutiny.

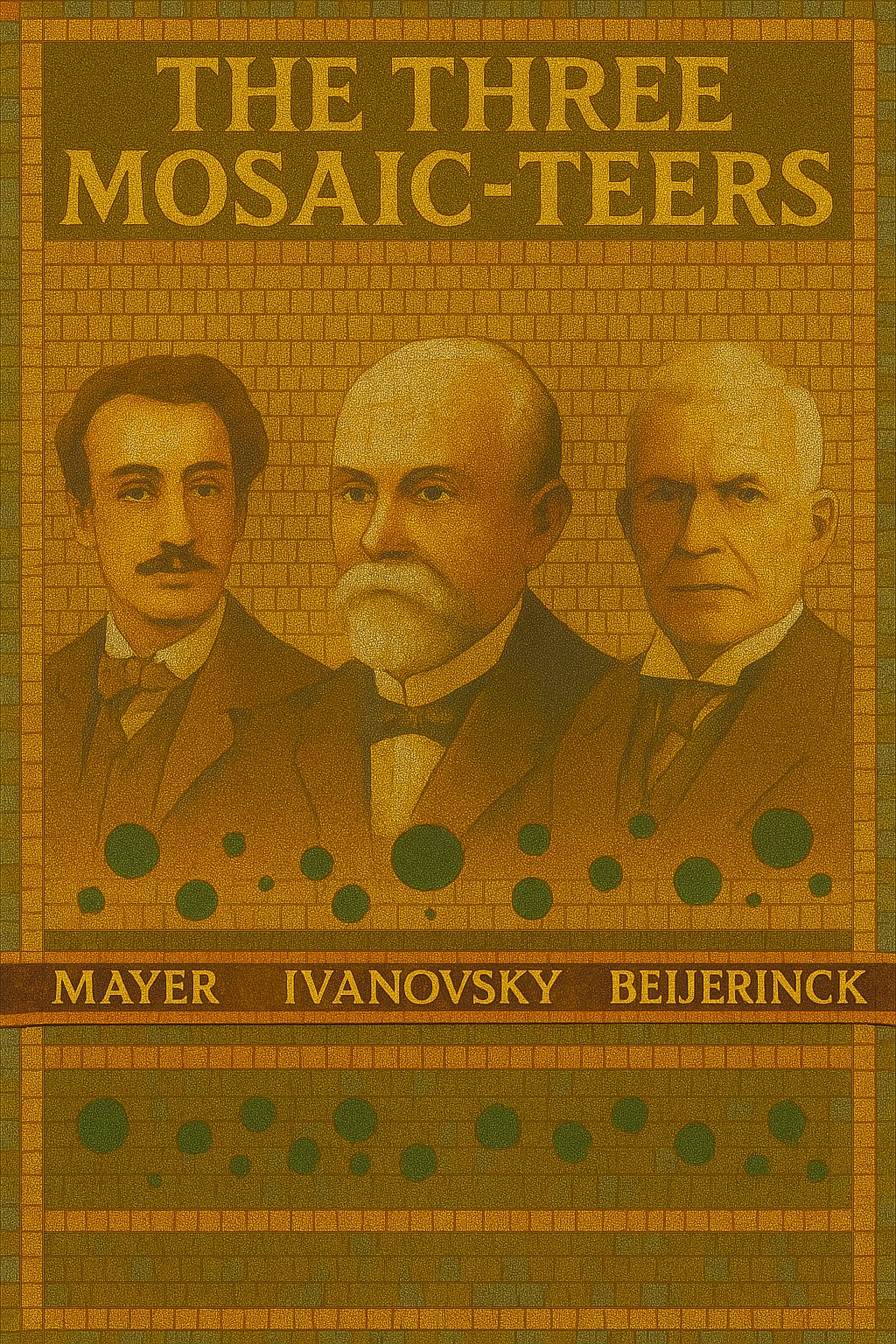

The Three Mosaic-Teers

Tobacco-Mosaic “Virus” (TMV) is the invisible agent that became associated with tobacco mosaic disease—a plant condition marked by mottling, yellowing, leaf curling, stunted growth, and necrosis. The disease caused major economic losses, prompting governments and institutions to investigate its cause, with the early focus placed squarely on identifying a microbial culprit.

It was through the independent efforts of three investigators—Adolf Mayer (1879), Dmitri Ivanovsky (1892), and Martinus Beijerinck (1898)—that the first “virus” was eventually declared. Notably, none of them were able to identify a microbial cause or satisfy the criteria later known as Koch’s Postulates, which remain the gold standard for establishing causation in “infectious” disease.

As recounted in Fields Virology, Adolf Mayer—a German scientist trained in chemical technology—was the first to investigate and name the disease in 1879. He mechanically transferred sap from diseased to healthy plants by sucking the emulsion of a ground diseased tobacco leaf into a capillary glass tube and injecting this into a large leaf vein of a healthy plant. Mayer reported that in nine out of ten cases, this process caused visible disease.

However, despite being able to induce symptoms experimentally, Mayer was unable to isolate a bacterial or fungal agent to account for the effect. Even though Koch’s Postulates had not yet been fully published, Mayer’s experiments failed to meet the logical requirements necessary to establish a causative agent of disease.

In a candid statement from 1882, Mayer speculated that the cause might be a “soluble, possibly enzyme-like contagium”—something too small to be filtered out or seen. Yet he admitted that “almost any analogy for such a supposition is failing in science.” This was an acknowledgment that he was observing symptoms without identifying a direct cause—essentially diagnosing by effect alone. In doing so, Mayer committed multiple logical fallacies: he affirmed the consequent by inferring a specific invisible agent solely from the presence of symptoms; he begged the question by presupposing the existence of such an agent to explain the very symptoms that were his only evidence; and he committed a false cause fallacy by assuming that symptom onset was caused by this hypothesized agent simply because it followed inoculation.

Interestingly, in a later 1886 paper, Mayer contradicted his earlier admission and claimed the disease was bacterial, despite no “infectious” forms having been isolated or described. This shift underscores the speculative and inconsistent nature of his conclusions—drawn from experiments that lacked a valid independent variable in the form of an identified, isolated agent, and that failed to include proper controls to rule out alternative causes such as chemical toxins, enzymes, or mechanical damage. Mayer’s interpretation was shaped more by prevailing assumptions than by conclusive evidence.

Adolf Mayer (1843–1942), a German scientist trained in the field of chemical technology (who had studied fermentation and plant nutrition), became the director of the Agricultural Experiment Station at Wageningen, Holland, in 1876. A few years later (1879), he began his research on diseases of tobacco and, although he was not the first to describe such diseases, he named the disease tobacco mosaic disease after the dark and light spots on infected leaves. In one of Mayer's experiments, he inoculated healthy plants with the juice extracted from diseased plants by grinding up the infected leaves in water. This was the first experimental transmission of a viral disease of plants, and Mayer reported that, “in nine cases out of ten (of inoculated plants), one will be successful in making the healthy plant ... heavily diseased” (109). Although these studies established the infectious nature of the disease, neither a bacterial nor a fungal agent could be consistently cultured or detected in these extracts, so Koch's postulates could not be satisfied. In a preliminary communication in 1882 (108), he speculated that the cause could be a “soluble, possibly enzyme-like contagium, although almost any analogy for such a supposition is failing in science.” However, 4 years later, in his definitive paper on this subject, Mayer concluded that the mosaic disease “is bacterial, but that the infectious forms have not yet been isolated, nor are their forms and mode of life known” (109).

The second researcher to investigate tobacco mosaic disease was Russian scientist Dmitri Ivanovsky. He essentially repeated Adolf Mayer's earlier work, with one critical addition: he passed the “infectious” sap through a Chamberland filter, designed to retain bacteria. When the filtered sap still caused disease in healthy plants, Ivanovsky concluded that something smaller than known bacteria must be responsible.

The next step was taken by Dimitri Ivanofsky (1864–1920), a Russian scientist working in St. Petersburg. In 1887 and again in 1890, Ivanofsky was commissioned by the Russian Department of Agriculture to investigate the cause of a tobacco disease on plantations in Bassarabia, Ukraine, and the Crimea. Ivanofsky rapidly repeated Mayer's observations, demonstrating that the sap of infected plants contained an agent able to transmit the disease to healthy plants, and he added one additional step. He passed the infected sap through a filter that blocked the passage of bacteria—the Chamberland filter, made of unglazed porcelain. The Chamberland filter, perfected to purify water by Charles Chamberland, one of Pasteur's collaborators, contained pores small enough to retard most bacteria. On February 12, 1892, Ivanofsky reported to the Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg that “the sap of leaves infected with tobacco mosaic disease retains its infectious properties even after filtration through Chamberland filter candles” ( 79). The importance of this experiment is that it provided an operational definition of viruses, an experimental technique by which an agent could qualify as a virus.

On February 12, 1892, he reported to the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg that “the sap of leaves infected with tobacco mosaic disease retains its infectious properties even after filtration through Chamberland filter candles.” This experiment has since been described as having “provided an operational definition of viruses”—a technique by which an agent could supposedly qualify as a “virus.”

However, this assertion reveals a foundational flaw in virology: it transformed an assumption into a definition. Ivanovsky, like Mayer, failed to identify any causative agent, and did not satisfy Koch’s Postulates. He did not observe, isolate, or purify a specific agent. Instead, he inferred that some invisible entity—presumably smaller than a bacterium—must be present because disease symptoms followed inoculation with filtered sap. Also like Mayer before him, Ivanovsky’s flawed reasoning commits multiple logical fallacies: it affirms the consequent by assuming that symptoms confirm the presence of an invisible agent; it begs the question by using symptoms—the only evidence—to infer the existence of the very agent presumed to cause them; and it commits a false cause fallacy by assuming that symptom onset was caused by the filtered material simply because it preceded it.

Ivanovsky speculated that the agent could be a toxin, but still clung to the idea of a bacterial cause—even though no bacteria could be cultured. Bound by the dominant bacteriological paradigm of his time, he even considered that the filter may have been faulty. As late as 1903, in his doctoral thesis, Ivanovsky had still not abandoned the bacterial hypothesis, insisting that the disease could ultimately be explained by bacteria that had eluded cultivation.

Ivanofsky, like Mayer before him, failed to culture an organism from the filtered sap and failed to satisfy Koch's postulates. He, too, was bound by the paradigm of the times suggesting that the filter might be defective or something might be wrong with his methods. He even suggested the possibility that a toxin (not a living/reproducing substance) might pass through the filter and cause the disease. As late as 1903, when Ivanofsky published his thesis (80), he could not depart from the possibility that bacteria caused this disease and that he and others had somehow failed to culture them. The dogma of the times and the obvious success of Koch's postulates kept most scientists from interpreting their data in a different way. It is equally curious that, at this time (1885), Pasteur was working with viruses and developing the rabies vaccine (117) but never investigated the unique nature of that infectious agent.

According to Alfred Grafe’s A History of Experimental Virology, Ivanovsky did not follow the established rules of etiological experiments and arrived at false conclusions. He never provided direct evidence in support of a bacterial cause, nor did he entertain the idea of a new type of “infectious” agent. In fact, he once claimed to have induced the disease using a bacterial culture, believing the issue could be solved without resorting to the “bold hypothesis” of proposing an entirely new kind of entity like a “virus.” This was in response to a hypothesis proposed by the third researcher involved in the “discovery” of TMV, Martinus Beijerinck.

Beijerinck essentially repeated Ivanovsky’s work, though he was seemingly unaware of the Russian scientist’s research. The key distinction was that Beijerinck observed the filtered sap could be diluted and still regain potency after passing through living plant tissue—suggesting it could “replicate,” but only in living cells, not in cell-free sap. This ruled out a toxin and led him to propose a self-replicating, filterable agent smaller than bacteria. He called it a contagium vivum fluidum—a contagious living fluid.

Ivanovsky, however, strongly rejected Beijerinck’s hypothesis. He wrote:

“We see that there is not a single fact which supports the hypothesis on the soluble character of the infectious agent of mosaic disease. On the contrary, the experiment with the diffusion into agar and especially the fractionated filtration clearly indicates that we are dealing with a contagium fixum.”

Ivanovsky’s arguments were persuasive enough that the examiners of his doctoral thesis concluded he had refuted Beijerinck’s hypothesis. Still, the debate over whether the agent was liquid or particulate in nature persisted for decades.

The third scientist to play a key role in the development of the concept of viruses was Martinus Beijerinck (1851–1931), a Dutch soil microbiologist who collaborated with Adolf Mayer at Wageningen. Beijerinck also showed that the sap of infected tobacco plants could retain its infectivity after filtration through a Chamberland candle filter. [He was unaware of Ivanofsky's work at the time (1898).] He then extended these studies by showing that the filtered sap could be diluted and then regain its “strength” after replication in living, growing tissue of the plant. The agent could reproduce itself (which meant that it was not a toxin) but only in living tissue, not in the cell-free sap of the plant. This explained the failure to culture the pathogen outside its host, and it set the stage for discovery of an organism smaller than bacteria (a filterable agent), not observable in the light microscope, and able to reproduce itself only in living cells or tissue. Beijerinck called this agent a “contagium vivum fluidum” (9), or a contagious living liquid. This concept began a 25-year debate about the nature of viruses; were they liquids or particles? This conflict was laid to rest when d'Herelle developed the plaque assay in 1917 (33) and when the first electron micrographs were taken of tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) in 1939 (88).

While Beijerinck's work essentially established the “virus” concept, according to Grafe, his idea about the causative agent being a liquid toxin rather than “infectious” particles was disregarded, rejected, and no longer discussed at the time. Grafe mentioned that even though Beijerinck’s ideas were close to the concept of the “virus” as it is known today, he made no attempt, theoretical or experimental, to prove or even to defend his hypothesis that the “infectious” agent was a contagious living fluid. Like his predecessors, he relied on unsound reasoning, committing the fallacies of affirming the consequent, begging the question, and false cause—inferring causation from correlation without identifying any direct mechanism or isolating a specific agent.

Regardless, as Fields Virology acknowledges, Mayer, Ivanovsky, and Beijerinck were all instrumental in the formation of the “virus” concept. At the time, the term virus—Latin for “slimy liquid” or “poison”—was used loosely to describe any “infectious” agent. It was eventually applied to the tobacco mosaic disease, not as a precise identification, but as a conceptual placeholder. TMV became the prototype of this new class of agents—not because conclusive evidence confirmed its nature or even its existence, but because no explanation could satisfy Koch’s Postulates or meet the standards of logical and scientific rigor. In effect, the idea of the “virus” emerged from a failure to prove causation.

Thus, Mayer, Ivanofsky, and Beijerinck each contributed to the development of a new concept: a filterable agent too small to observe in the light microscope but able to cause disease by multiplying in living cells. Loeffler and Frosch (101) rapidly described and isolated the first filterable agent from animals, the foot-and-mouth disease virus, and Walter Reed and his team in Cuba (1901) recognized the first human filterable virus, yellow fever virus (122). The term virus [from the Latin for slimy liquid or poison (76)] was at that time used interchangeably for any infectious agent and so was applied to TMV. The literature of the first decades of the 20th century most often referred to these infectious entities as filterable agents, and this was indeed the operational definition of viruses. Sometime later, the term virus became restricted in use to those agents that fulfilled the criteria developed by Mayer, Ivanofsky, and Beijerinck and that were the first agents to cause a disease that could not be proven by using Koch's postulates."

The fact that Mayer, Ivanovsky, and Beijerinck failed to logically or scientifically prove that any entity caused tobacco mosaic disease should raise serious red flags about the claim that a “virus” was discovered. They never isolated or purified any microbe as an independent variable to be used in scientific experiments to determine causation. Instead, they recreated nonspecific disease symptoms by mechanically injuring plants and rubbing unpurified fluids into the wounds—without using proper controls involving healthy plants treated identically. Had they done so, they might have realized that the inoculation method itself was to blame.

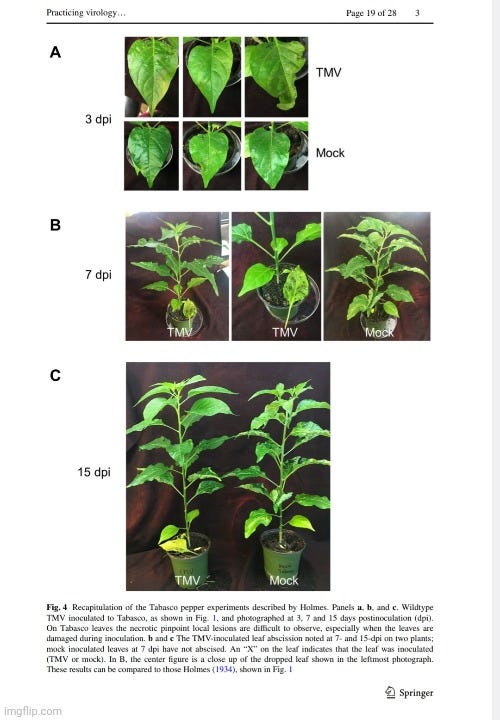

This was demonstrated in the paper Practicing virology: making and knowing a mid-twentieth century experiment with Tobacco mosaic virus published in 2022. In the revealing paper, Scholthof et al. set out to replicate a classic experiment from the 1930s that helped cement the “viral” paradigm in plant pathology. What they ended up documenting, however—perhaps unintentionally—is a striking case study in just how fragile, imprecise, and assumption-dependent the entire framework of experimental virology really is.

The paper detailed the researchers attempts to replicate the work of Francis O. Holmes, a virologist at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. In the late 1920s, Holmes developed and standardized the rapid and efficient inoculation method now known as mechanical (or rub) inoculation—a technique based on principles already used by Mayer, Ivanovsky, and Beijerinck, who also relied on mechanical injury to transmit “infectious” sap to healthy plants, though without formalizing the process.

Scholthof et al. used the rub-inoculation method, following Holmes’ technique, to apply sap from “TMV-infected” leaves to healthy tobacco and pepper plants. Leaves were gently abraded with carborundum or Celite to allow “virus” entry, then rinsed. Plants were observed daily for symptoms such as lesions, mottling, and leaf abscission.

Unexpectedly, both mock-inoculated (control) and TMV-inoculated Tabasco and bell pepper plants showed leaf drop, which they found puzzling since rapid abscission is typically associated with the L-gene in “TMV-infected” plants. Historical findings by Holmes also noted that leaf drop can occur in older plants or under varying environmental conditions. This should have completely undermined the interpretation that TMV caused the leaf drop. When the negative control exhibits the outcome attributed to a “virus,” the hypothesis is falsified—or should have been.

The researchers shifted focus to possible contributing factors: environmental conditions, potential contamination in mock controls, genetic variability in the California Wonder pepper strain, and even the inoculation method itself. They noted that although TMV rub-inoculation is widely used in plant pathology labs due to its perceived simplicity, it is notoriously prone to errors. Overly vigorous rubbing can damage leaves, and outcomes can vary based on the materials used and a host of other circumstantial features—despite the method being standardized since the 1930s. In other words, the technique itself was a major determining factor in producing disease—whether or not TMV was presumed to be present.

They concluded:

“In our pursuit of a decades old experiment using established, standard methodology we found nearly every element (soil, watering regimen, plants, lighting, inoculum, and pest control measures) affected our ability to make and learn from Holmes. This has ramifications for scientists and historians who decide to replicate key experiments in their field.”

While Scholthof et al. intended to honor Holmes’ foundational work in virology, what they’ve actually done is expose how unstable that foundation is. The symptoms attributed to TMV appeared in the controls. The techniques used to induce symptoms were themselves inherently injurious. The outcomes were shaped by a multitude of uncontrolled variables. And the conclusions did not emerge from dispassionate observation, but from belief sustained through methodological ritual—one that traces directly back to Mayer, Ivanovsky, and Beijerinck. These early pioneers filtered plant sap and applied it to wounded leaves, interpreting resulting symptoms as proof of a “virus,” despite never isolating one. Scholthof’s modern homage ends up confirming the same thing: the method makes the “virus”—not the other way around.

Had Mayer, Ivanofsky, and Beijerinck not confined themselves to a microbial hypothesis for tobacco mosaic disease, they may have recognized that other factors—not a mysterious “virus”—were responsible for the symptoms they observed. It is now well-established that these symptoms vary depending on the plant species and the environmental conditions, which can either bring out or mask signs of disease. The symptoms attributed to TMV are known to result from a wide range of non-“viral” factors, including high temperatures, insect feeding, growth regulators, herbicides, mineral deficiencies, and even mineral excesses.

Moreover, every hallmark symptom—leaf distortion or deformation, mosaic patterns of light and dark green (or yellow and green), chlorotic mottling, necrotic spotting, flower color breaking, and general stunting—is nonspecific. In other words, no symptom can be definitively tied to TMV. Diagnosis based on symptoms alone is not possible and ultimately circular, especially when the inoculation method itself is damaging and the presence of TMV is assumed rather than demonstrated.

And that’s assuming symptoms show up at all. Growers are instructed to inspect incoming plant material for visible signs of disease, but also to randomly sample asymptomatic plants for testing—since “infection” is said to occur even in the absence of symptoms. Currently, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are the main methods used to detect TMV. Detection is said to be challenging, as TMV may be unevenly distributed in plant tissues and present at low levels, allowing it to go undetected. It’s not uncommon, we’re told, for symptoms to be delayed by weeks after initial “infection.” Some “attenuated strains” of TMV are said to cause no symptoms at all, and may even suppress symptoms when coexisting with more “virulent” strains in the same plant.

Despite this, it is asserted that once a plant is “infected,” it remains so for life—even if it never shows signs of illness. The “infection” is not typically passed through seed to offspring, but when it is detected in progeny, mechanical damage during transplanting is blamed for introducing the “virus.” Yet as Scholthof et al. demonstrate, mechanical damage alone is sufficient to explain the observed disease symptoms without the presumed “viral” presence.

In short, TMV stretches the boundaries of logic and rests on an unfalsifiable premise: that healthy carriers—plants with no signs of disease—can still be considered “infected” by an invisible agent, whose presence is assumed rather than proven. This belief hinges not on direct observation or causal demonstration, but on inference layered atop inference—beginning with Mayer, Ivanovsky, and Beijerinck. None of them isolated a causal agent. None fulfilled Koch’s Postulates. Each interpreted the emergence of nonspecific symptoms after sap inoculation as confirmation of an “agent,” without considering that the symptoms were themselves the result of the invasive procedure or other environmental stressors. Their reasoning was circular: assuming an invisible agent causes disease, and then interpreting any sign of disease—even in wounded or healthy plants—as evidence of that agent.

By ignoring alternative explanations and failing to rule out mechanical injury, toxicity, or nutritional imbalance, these early virologists built a hypothesis on methodologically compromised ground. Worse, they presented their conclusions as if the agent had been conclusively demonstrated, when in reality no such entity had been purified, visualized, or shown to act alone in producing disease. Over time, this logical sleight of hand solidified into scientific dogma, carried forward by rituals of symptom-based diagnosis, belief in asymptomatic “infections,” and the use of indirect molecular assays that presuppose what they claim to detect. The concept of TMV, like that of the “virus” itself, was never discovered—it was constructed. And from the very beginning, that construction was riddled with fallacies.

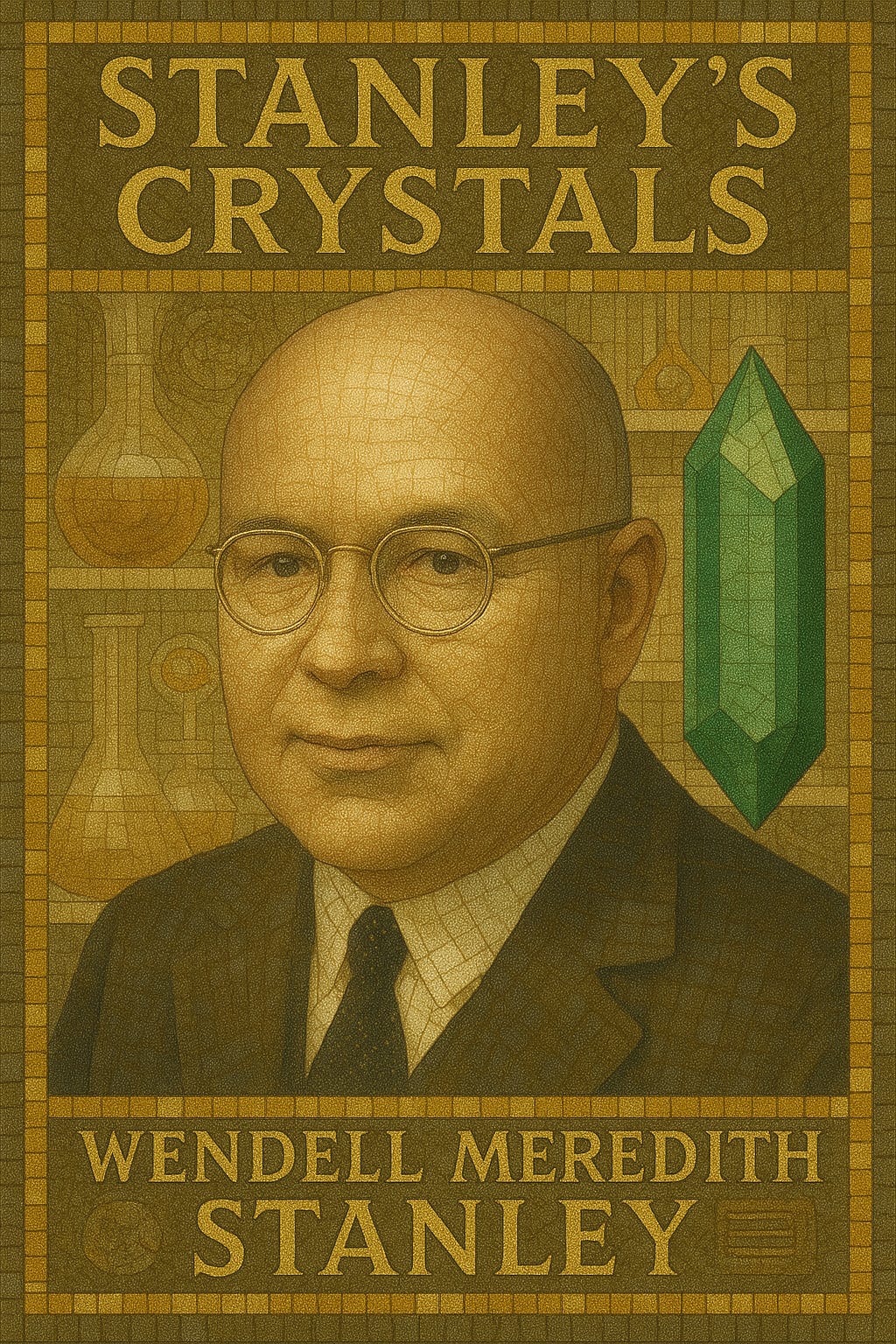

Stanley's Crystals

As Mayer, Ivanovsky, and Beijerinck did not purify, isolate, or identify a causative agent at the time the “virus” concept was established, questions remained as to whether the observed effects in plants were caused by a toxic fluid or an unseen particle. According to historian Tor van Halvoort's 1993 book Research styles in virus studies in the twentieth century: controversies and the formation of consensus, interpretations of the tobacco mosaic “virus” ranged from a small microbe or ultramicrobe to a chemical compound produced by the plant itself—i.e., endogenous rather than exogenous—well into the 1930s.

Several researchers at the time rejected the idea that tobacco mosaic disease was caused by an outside invader. In 1899, Albert Woods supported the enzymes oxidase and peroxidase as possible causes. Woods, drawing from experiments that artificially induced mosaic symptoms in plants, concluded the cause was internal to the plant. He noted that rapidly growing tobacco plants, when cut back, produced new leaves with mosaic-like mottling:

“The young shoots grew very rapidly and were invariably mottled and often distorted exactly as in the mosaic disease.”

Other researchers shared Woods’s endogenous view, including Kurt Heintzel, who also pointed to oxidase activity, and Friedrich Hunger, who believed it was a metabolic disorder. German geneticist and botanist Erwin Baur questioned the strictly parasitic model of plant disease. Studying “infectious” variegation (chlorosis) in Abutilon, Baur observed that variegated and non-variegated plants could grow side by side without signs of transmission. Since he could induce the condition through artificial means, he concluded that some “infectious” plant diseases were not caused by living organisms. Baur warned that clinging to “the old dogma of the unconditionally parasitic nature of all infectious disease” was an impediment to progress.

Support for a chemical-toxin model continued well into the 1930s. In 1931, Vinson and Petre described the tobacco mosaic “virus” as behaving chemically, concluding:

“...it is probable that the virus which we have investigated reacted as a chemical substance.”

Their findings were reaffirmed in 1933 by Barton-Wright and McBain, who replicated the experiments and stated:

“We have repeated this work in detail and confirmed it in every particular, and we are also of the opinion that the virus in this case behaves as a chemical compound and not as a living organism.”

Despite this ongoing debate over whether “viruses” were chemical (endogenous) or physical (exogenous) entities, the matter was claimed to be “settled” in 1935 when American biochemist Wendell Meredith Stanley crystallized a substance presumed to contain the tobacco mosaic “virus.” His work became the cornerstone for the idea that “viruses” were self-replicating particles rather than chemical toxins and is still cited by virologists today as evidence of purification and isolation.

Stanley was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1946 “for their preparation of enzymes and virus proteins in a pure form.” According to the Nobel biography, prior to this achievement, “viruses” could only be inferred by the symptoms they produced, as they were too small to be seen under a microscope. The prize site states that Stanley succeeded in extracting the tobacco mosaic “virus” in pure crystal form.

“Many infectious diseases are caused by viruses—very small biological particles. They are far too small to be visible under a microscope and could only be identified with the help of the symptoms they cause. Wendell Stanley studied the tobacco mosaic virus, which attacks the leaves of tobacco plants. From considerable quantities of infected tobacco leaves, he succeeded in extracting the virus in the form of pure crystals in 1935. Through further research, Stanley was able to show that the tobacco mosaic virus is composed of protein and ribonucleic acid, or RNA.”

The American Association of Immunologists stated that, with his “isolation” and crystallization of TMV, Stanley demonstrated that “viruses” blurred the lines between the living organisms studied by biologists and the nonliving molecules studied by chemists. The Rockefeller University supports this narrative, stating that “viruses were the subject of both intense investigation and wild speculation until 1935, when Rockefeller Institute scientist Wendell M. Stanley purified the tobacco mosaic virus and made one of the most surprising discoveries of the 20th century: that a virus has properties definitive of both living and nonliving matter.” Thus, this was clearly a key moment in the history of virology—one that allowed proponents to have their cake and eat it too, conveniently bypassing the scientific standards applied to both biology and chemistry.

However, did Stanley really do all that is claimed? In his 1935 paper Isolation of a Crystalline Protein Possessing the Properties of Tobacco-Mosaic Virus, Stanley himself asserted to have isolated a crystalline protein from juice of “infected” Turkish tobacco plants that retained the biological activity attributed to the tobacco mosaic “virus.” He described the material as proteinaceous based on positive reactions with several protein-detecting reagents and chemical composition (20% nitrogen). His method involved sequential chemical fractionation—using ammonium sulfate precipitation, pH adjustments, lead subacetate, and celite filtration—to remove visible contaminants, followed by crystallization under specific salt and pH conditions. The resulting crystals were considered “highly infectious” when diluted and rubbed on susceptible plants, which Stanley took as confirmation of the presence and purity of the “virus.”

Yet Stanley’s interpretation rested on a series of unverified assumptions and methodological limitations. Crucially, he never demonstrated that a discrete, uniform “viral” particle was present in the crystals. Instead, he assumed that the observed “infectivity” was caused by a single molecular species—an assumption that commits the false cause fallacy. His claim of “purity” relied not on direct evidence, but on affirming the consequent: the crystals caused lesions, lesions are associated with “infection,” therefore the crystals must contain the “infectious” agent. But correlation does not confirm identity or purity.

Moreover, Stanley inferred “infectivity” solely from lesion counts on test plants—without visualizing or isolating any distinct particle. This amounts to begging the question, as he presupposed the presence of a “virus” to validate its detection. And with no access to electron microscopy or ultracentrifugation at the time, he lacked the tools to characterize particle morphology or confirm homogeneity. These interpretive leaps, resting on indirect effects rather than direct observation, opened the door to misattribution and overconfidence in what the crystals actually contained.

In a notably candid conclusion, Stanley acknowledged the difficulty—if not impossibility—of proving the purity of a protein, and merely assumed that a “virus” required living cells for replication, as this was not experimentally demonstrated:

“Although it is difficult, if not impossible, to obtain conclusive positive proof of the purity of a protein, there is strong evidence that the crystalline protein herein described is either pure or is a solid solution of proteins. As yet no evidence for the existence of a mixture of active and inactive material in the ciystals has been obtained. Tobacco-mosaic virus is regarded as an autocatalytic protein which, for the present, may be assumed to require the presence of living cells for multiplication.”

Stanley’s admission is telling. Rather than offering definitive proof, he relied on assumptions—both about the purity of his crystalline product and the nature of “viral” replication in living cells. This ambiguity did not go unnoticed. In the paper The discovery of the chemical nature of tobacco mosaic virus, the authors concluded that although Stanley is widely credited with elucidating the nature of the “virus,” clear “proof of ambiguity” can be found throughout his work.

Within a few weeks of the publication, Stanley was criticized by phytopathologist Frederick Bawden and biochemist Bill Pirie. The English researchers had prepared “liquid crystalline” TMV substances that resulted in chemical analyses of the preparations that differed from the data reported by Stanley. Pirie would later repeatedly accuse Stanley of gradually assimilating their data to avoid the need of revoking his early claim that he really had isolated TMV in 1935. Regardless, Bawden and Pirie challenged this isolation as they questioned whether the material they had “isolated” was the “virus” as it truly was inside the “infected” plant. They stated in 1936:

“[W]e feel that it is still not proved, nor is there any evidence that the particles we have observed exist as such in infected sap.”

Bawdin and Pirie argued that the very process of “isolating” tobacco mosaic “virus” material resulted in the loss of the defining characteristic that originally distinguished it from bacteria—its ability to pass through fine filters. As they put it:

“During the processes of purification ... the virus undergoes a change that is not readily reversed, and loses completely the property that first distinguished tobacco mosaic virus as a new type of disease agent, namely, that it should pass fine filters.”

Additionally, they found evidence suggesting that TMV existed within plant cells as insoluble complexes. This led them to conclude that when making extracts from “infected” leaves—by separating the presumed “virus” from plant tissue and cell debris—essential components of the “virus” might be lost in the process. As a result, Bawden and Pirie rejected the notion that the isolated “crystalline” preparation represented a pure sample of tobacco mosaic “virus.” In fact, they viewed plant “viruses” as nucleo-proteins—molecules not fundamentally different from normal components produced by the host cell. This suggests that the particles claimed to be TMV are actually endogenous to the plant, rather than exogenous invaders.

A later paper, W. M. Stanley’s Crystallization of the Tobacco Mosaic Virus 1930-1940 agreed with Bawdin and Pirie on the lack of purity of the crystalized preparations, identifying major technical flaws and experimental oversights in Stanley's work. Contrary to Stanley’s claims, his “pure” TMV crystal was later revealed to be chemically impure—containing water, residual plant components, and a substantial amount of non-protein material.

The authors noted that Stanley made claims without adequate evidence, and he benefitted greatly from social and institutional affiliations, particularly with The Svedberg and Arne Tiselius of the University of Uppsala and the Rockefeller Institute, where Stanley's work received high-level support. Tiselius’s influence with the Nobel Committee helped secure Stanley the chemistry prize, despite the questionable foundation of his claims:

“Yet Stanley’s work was flawed by technical errors and misconceptions. As several critics in the late 1930s pointed out, without receiving much attention, his virus sample contained water and impurities and thus was not a true crystal. It also contained a significant fraction of nonprotein material-about 6 percent nucleic acid (RNA)-which Stanley had missed entirely, and which turned out to be the crucial component, the viral hereditary material. Furthermore, the property of self-replication in viruses was not based on enzyme action and crystal growth, as Stanley often claimed without adequate evidence, but turned out to be a direct consequence of the structure of nucleic acids. How can we explain these technical and conceptual errors in the light of the international recognition bestowed on the young Stanley and his leadership in science?”

“Stanley also drew heavily on the protein researches and on the scientific reputation of The Svedberg and Arne Tiselius at the University of Uppsala. The Uppsala group had a special relationship with the Rockefeller Institute and shared its sophisticated Swedish technology and its laboratory expertise, as well as some scientific biases, with members of the institute. In cultivating the Uppsala connection, Stanley benefited from technological and social advantages that placed his laboratory in the vanguard of research. Tiselius’s support and influence carried considerable weight with the Nobel Committee in awarding Stanley the chemistry prize (Tiselius himself was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1948).3”

“Physicochemical techniques alone did not uncover the key to biological knowledge. Eventually Stanley’s errors were corrected, his results reinterpreted, and old theories discarded, reintegrating Stanley into an account of biology that is “restricted to the enumeration of successful investigations.”

Even though Stanley’s work has been promoted as the definitive proof of a purified “viral” particle and as the foundation for elucidating the true nature of the “virus,” his conclusions were fundamentally flawed. They rested on indirect biochemical measurements, unverified assumptions about replication and structure, and the absence of definitive purification or direct visualization of a discrete, autonomous “viral” entity. Rather than isolating a uniquely identifiable “infectious” particle, Stanley worked with what he believed to be a “crystalline protein” capable of autocatalysis—an idea that was speculative and later contradicted by the “discovery” of nucleic acids as the “true” carriers of genetic information.

As Matthews’ Plant Virology later admitted, “Crystallization used to be taken as an important criterion of purity, but it does not distinguish components that co-crystallize with the infectious virus.” This casts further doubt on the assumption that Stanley’s crystalline product was “pure” or definitively “viral.” His interpretation was retroactively adjusted to fit into a developing “viral” paradigm, not because it objectively demonstrated the existence of “viruses” as defined today, but because institutional momentum, technological optimism, and social prestige demanded a story of success. Thus, Stanley’s findings were not the confirmation of “viral theory,” but the beginning of a narrative built upon reinterpretation and selective emphasis, rather than direct, falsifiable scientific demonstration.

Ruska's Particles

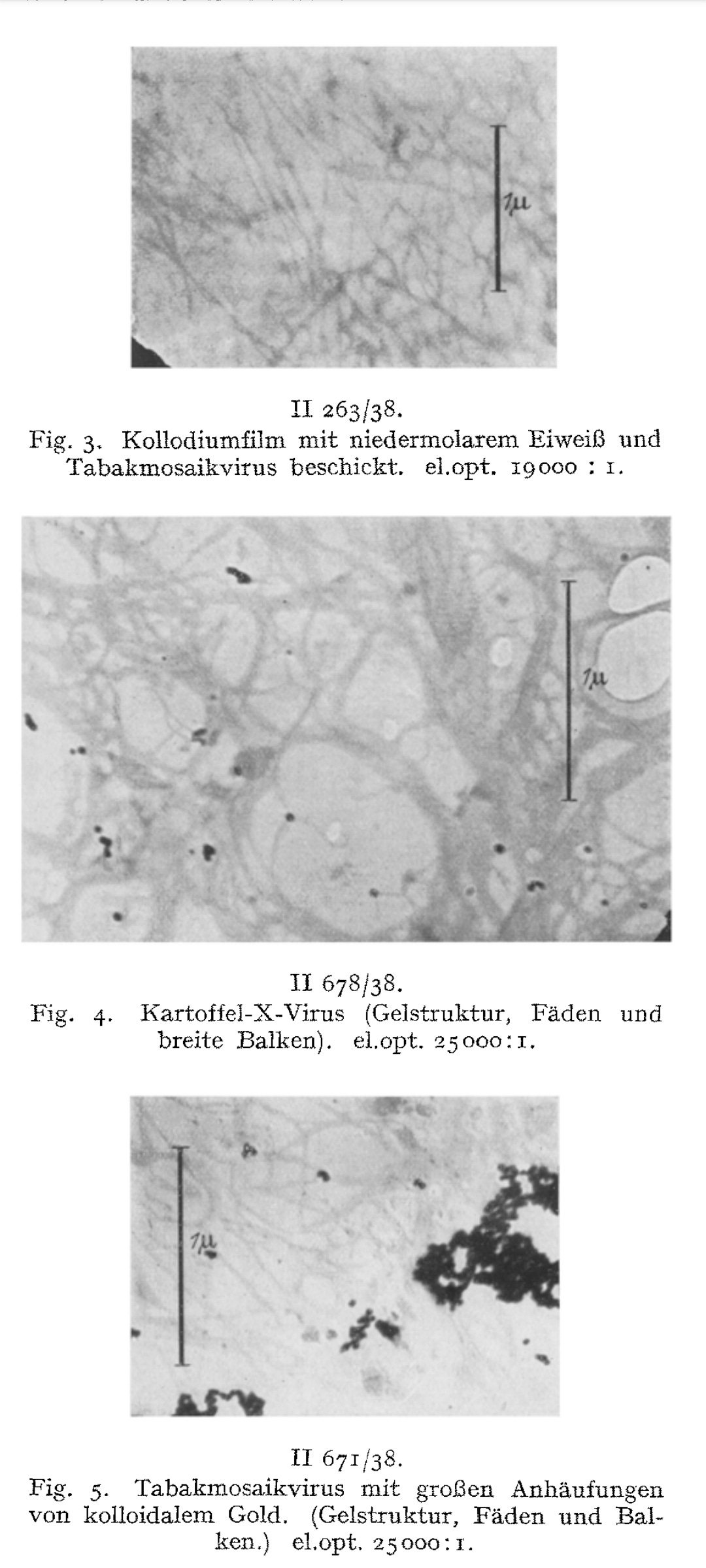

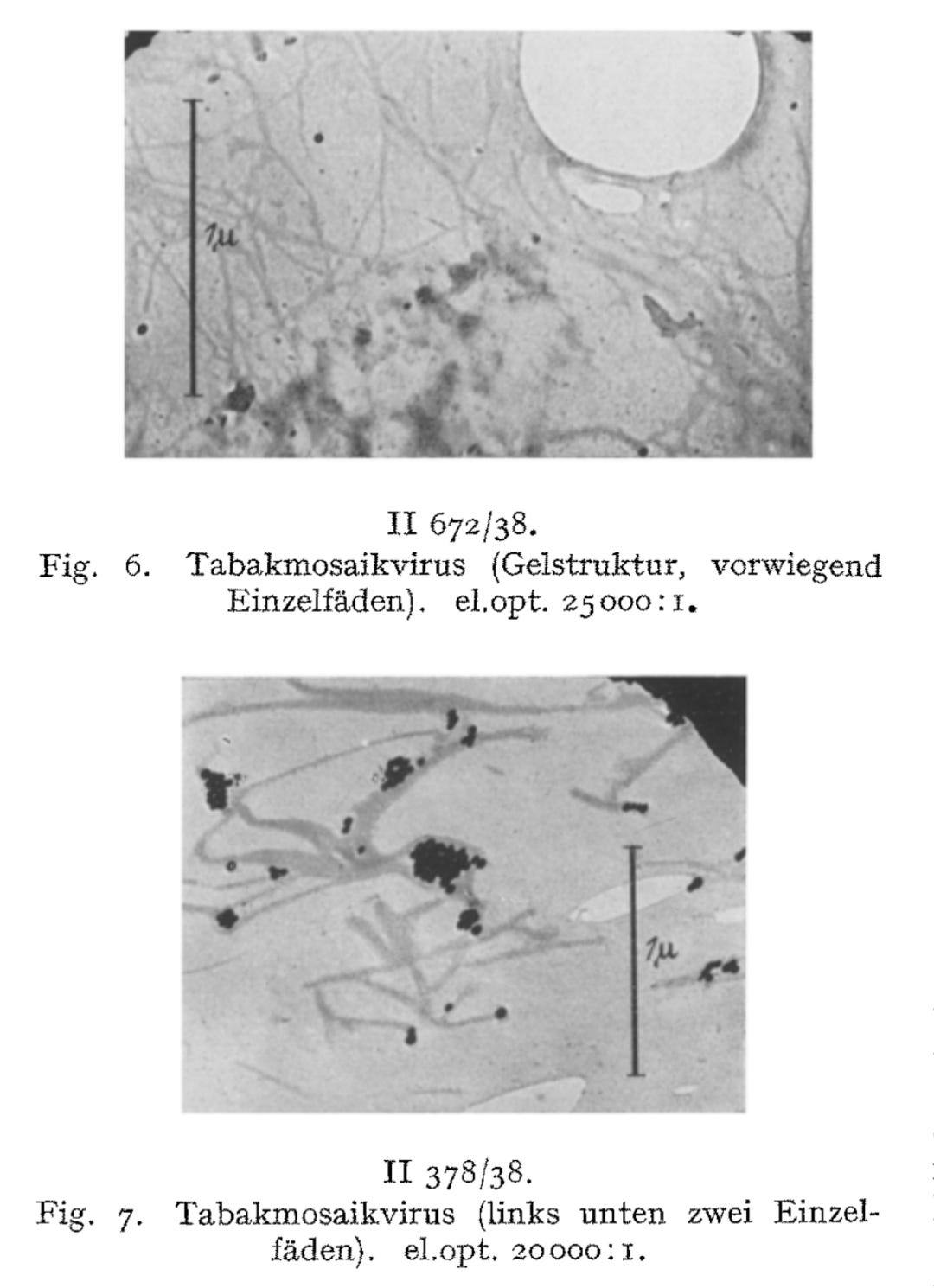

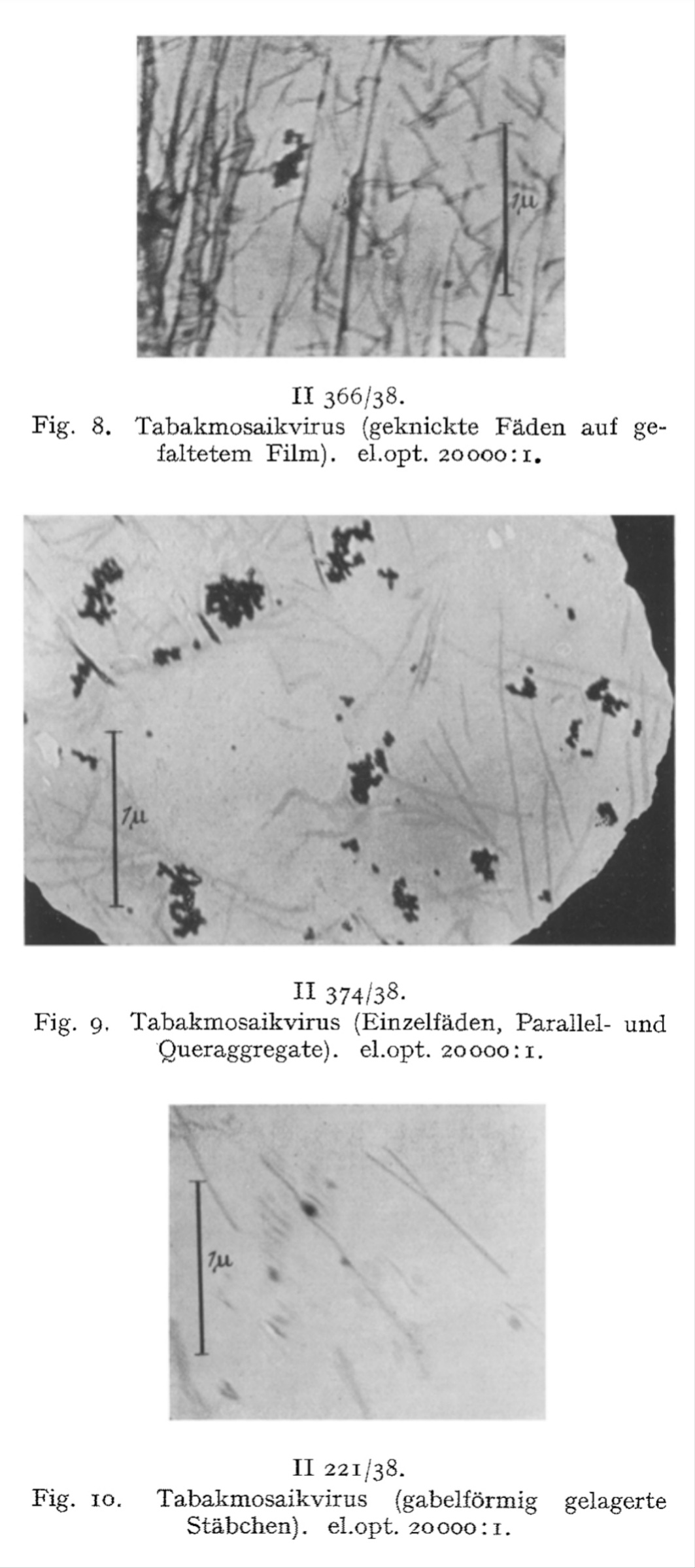

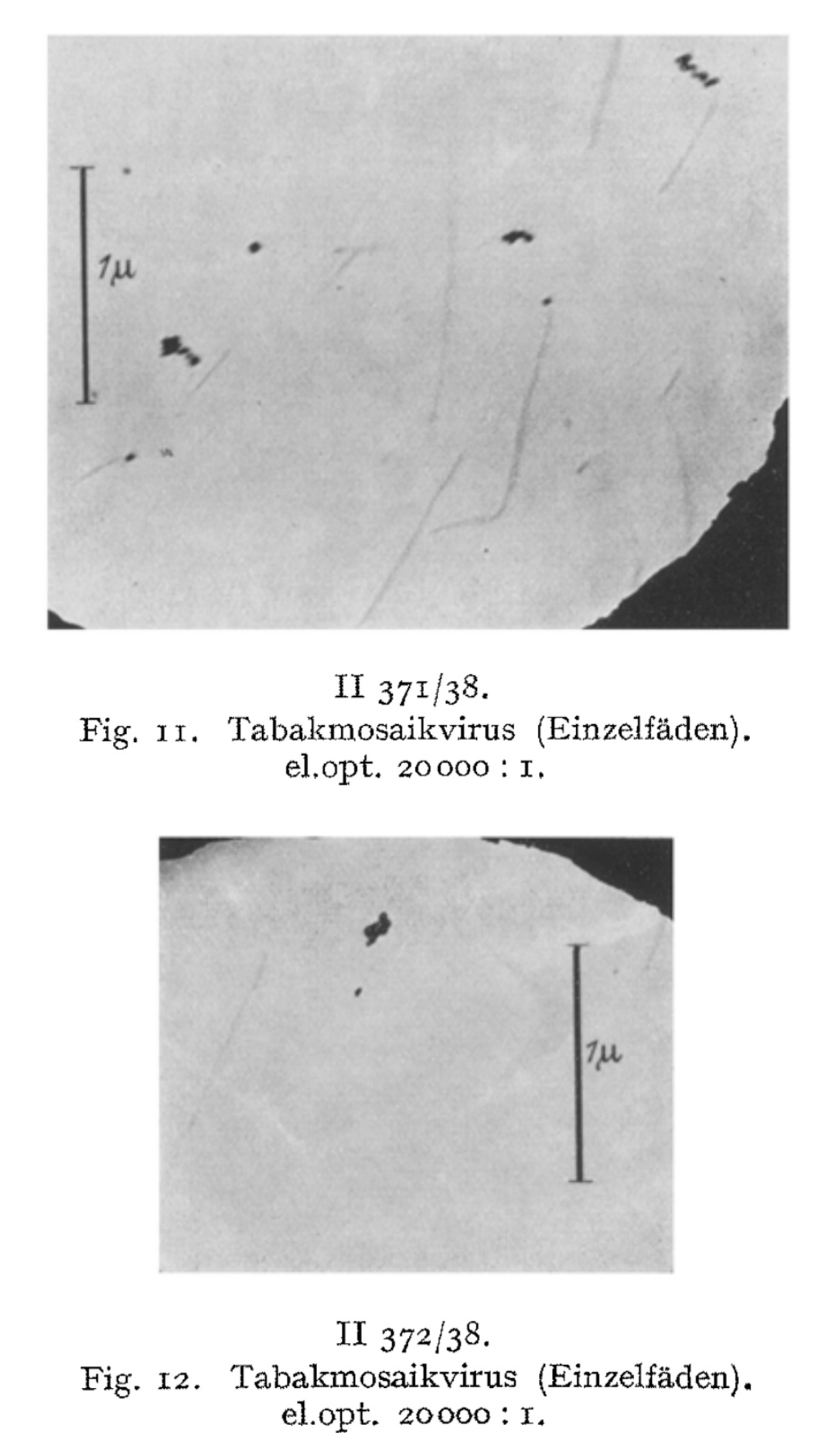

The lack of a purified and isolated particle proven to cause tobacco mosaic disease did not deter German electron microscopist Helmut Ruska from relying on prior investigations into “the probable shape, particle size of the final infectious unit, and the molecular weight of this viral protein” to guide his attempts at visualizing the presumed “virus” using the newly developed electron microscope in his 1939 paper Die Sichtbarmachung yon pflanzlichem Virus im Obermikroskop. Referring to Wendell Stanley’s 1935 claim, Ruska remarked that “Stanley’s surprising finding that the ‘pathogen’ of tobacco mosaic disease is a high-molecular protein has led to considerable research in recent years,” signaling both the influence and the uncertainty of Stanley’s conclusion. Ruska referenced indirect physicochemical methods—including behavior in solution, light scattering, and sedimentation rates—to determine what kind of particle to look for, reflecting a model-driven approach. He acknowledged that the available evidence was contradictory, yet used it to justify assumptions about the shape of the “virus.”

“The investigations were carried out using the X-ray method according to Debye–Scherrer, viscometry, the determination of the diffusion constant, the sedimentation constant, and the sedimentation rate in the gravitational field of high-speed centrifuges according to the method of Svedberg. The results of this work, although still contradictory in some points, justify the assumption that these viruses must be elongated molecules of very high molecular weight.”

Using this inferred framework, Ruska attempted to visualize TMV by applying a colloidal solution—a “virus sol”—from “infected” plant material onto a carrier film, allowing it to dry, and then imaging the residue with the electron microscope. Through this process, he observed rod- or thread-like structures which he measured to be about 300 millimicrons (300 nm) long and approximately 15 nm in diameter—dimensions consistent with those previously estimated via indirect methods such as ultracentrifugation and X-ray scattering.

These rod-like structures, he claimed, were the “virus” particles themselves. Ruska further speculated that clumping of these rods led to visible aggregations and even suggested that they had now directly visualized a previously hypothetical process—”virus aggregation.”

In the conclusion of the paper, Ruska summarized the key findings from their work, noting that they had demonstrated the possibility of imaging the “virus” particles.

Summary.

The possibility of making tobacco mosaic and potato X-virus visible and imageable under the microscope is demonstrated.

The preparative starting situation is described. When the virus sol dries out, a dry mass with a directional structure is formed on the carrier film.

With sufficiently diluted virus sols, it is possible to prevent lateral aggregation, so that the rods or threads dry out isolated from one another.

The measured dimensions of the smallest structures correspond to those determined by X-ray imaging and ultracentrifugation.

We consider the rod- or thread-like structures with dimensions of around 300 m/t or 150 m/t in length and around 15 m/t in diameter to be the molecules of the TM virus and regard multiples of these as linear or lateral aggregations.

In the sense of submicroscopic morphology, the fiber structure for the micellar to molecular range could be visualized and imaged for the first time on a protein dry gel.

We have directly visualized the aggregation of TM virus molecules, which was previously hypothetical and only demonstrated by indirect methods, and found it to be a surprisingly easy reaction, initially occurring in a linear chain, which continues continuously until the formation of light-microscopically and then macroscopically visible particles. Figs. 7-12 have in common that they exhibit thread- or rod-shaped individual particles that vary greatly in length but are quite uniform in width.

In view of this fact, the question arose as to whether these distinct individual particles should be regarded as the molecules of the TM virus, or as molecules aggregated predominantly in the longitudinal direction, or as supermolecular structures. The interpretation of the findings must be based on a comparison of the figures obtained from the indirect methods with the quantities measurable in these images, taking into account the resolution and imaging fidelity of the microscopy.

Yet even in light of these observations, Ruska posed a fundamental question: were these individual particles truly the molecules of the TM “virus,” aggregates predominantly aligned longitudinally, or supermolecular structures? He acknowledged that interpretations remained provisional, emphasizing the need to compare these images with the indirect measurements and consider resolution limits of the early electron microscope. This reveals that—for all his breakthroughs—Ruska recognized that he was operating at the outer limits of certainty.

While Ruska’s pioneering use of electron microscopy to visualize presumed “virus” particles was considered a technological milestone, his conclusions regarding the identity, structure, and “infectivity” of the tobacco mosaic “virus” rested on a series of unverified assumptions. These include equating visually observed rod-like structures with “viral” particles without adequate controls, extrapolating from poorly resolved images, combining inconsistent physicochemical data to estimate molecular weight, and failing to account for contamination or aggregation effects. Ruska’s reliance on indirect, model-driven reasoning—paired with a tendency to infer causality from correlation—ultimately weakened the reliability of his findings. Ruska’s paper reflects the limitations of early “virus” research, where the desire to visualize and name “the pathogen” substituted for rigorous demonstration of isolation and causative proof.

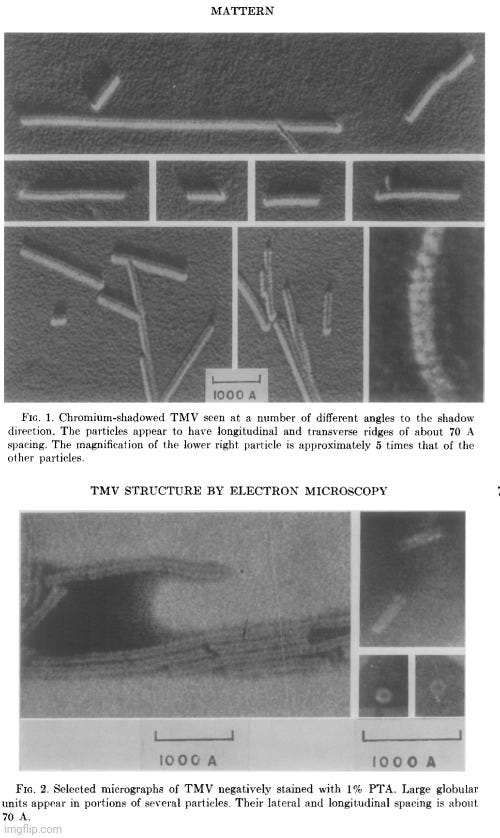

Despite the widespread reliance on indirect physicochemical methods—such as sedimentation rates, light scattering, and X-ray diffraction—to deduce the shape and structure of the presumed tobacco mosaic “virus,” even mid-20th-century researchers acknowledged unresolved contradictions between these model-based interpretations and actual electron micrographic observations. In the 1962 study Electron Microscopic Observations of Tobacco Mosaic Virus Structure, author Carl Mattern openly stated that electron microscopy had “failed to confirm convincingly the present view of TMV protein structure,” and that some of the visual data were “incompatible with the X-ray diffraction-deduced structure.”

“The current concept of the structure of tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) has been derived largely from X-ray diffraction studies and biochemical data. Singularly, little has been contributed by electron microscopy except the over-all dimensions of this rodlike plant virus. Not only has electron microscopy failed to confirm convincingly the present view of TMV protein structure, but the interpretations given some electron microscopic data appear to be incompatible with the X-ray diffraction-deduced structure.

This communication will present additional electron micrographic observations of what appear to be structural elements on the surface of TMV. These, too, present difficulties in that they appear to be incompatible with the current view of TMV structure. Several hypotheses are advanced as possible explanations for these apparent discrepancies.”

Mattern conceded that new EM observations only compounded the problem, as the visible surface features of TMV again failed to align with prevailing structural assumptions. He noted that the model of “virus” produced by X-ray diffraction had “not been confirmed convincingly by direct observation in the electron microscope.” He proposed several possible explanations: the features might be imaging artifacts, though this was unlikely given their reproducibility across multiple preparations and methods; they might result from structural shifts during sample preparation, such as dehydration or metal shadowing; or, more radically, they might point to limitations or inaccuracies in the prevailing structural model itself. Though the last possibility was considered least likely in the absence of a better-fitting model, the study underscored a fundamental tension: that different techniques produced contradictory representations of the same presumed structure. Mattern ultimately admitted that none of the proposed explanations fully resolved the inconsistencies, concluding that it was “imperative that there be found explanations for apparent discrepancies between the results obtained from these two disciplines.”

This directly contrasts with Helmut Ruska’s earlier insistence that indirect methods must ultimately be confirmed by compatibility with electron micrographs. While Ruska accepted that the available evidence for the shape of the “virus” was inconsistent, he still argued that visual observations must correlate with the theoretical models. That such compatibility remained elusive decades later casts serious doubt on the model-driven approach—and raises deeper questions about whether the structure, or even the very identity, of TMV was ever empirically confirmed.

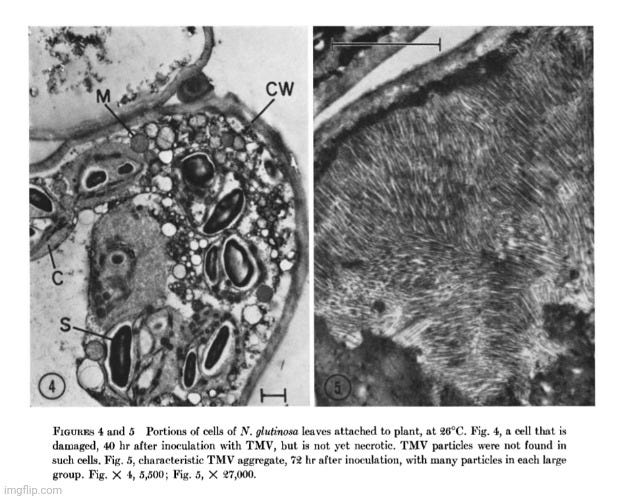

Further research adds to the growing evidence that the particles claimed to be a “pathogenic virus” responsible for tobacco mosaic disease are not what they are claimed to be. In the 1964 paper An Electron Microscope Study of Tobacco Mosaic Virus Lesions in Nicotiana glutinosa L., M. Weintraub, Ph.D., and H. W. J. Ragetli, Ph.D. aimed to detect the earliest cytological changes following inoculation with the presumed TMV and to follow the progression of those changes through to the terminal stages. To do so, they examined ultra-thin sections of Nicotiana glutinosa leaves at short intervals from 0 to 78 hours after inoculation with a concentrated solution of TMV.

Despite observing pathological changes over the entire timeframe, the researchers did not observe any structures at any stage that could be identified as TMV particles. This absence directly contradicts the expectation that a replicating “virus” should be visible, especially when using electron microscopy. Rather than question the assumption that a “virus” was responsible, the authors attempted to rationalize this damning evidence:

“The absence of recognizable virus particles in our sections, and our calculation that a very small amount of virus is synthesized, fits well with the hypothesis of Ackermann (1) that the primary cytopathogenic effect of viruses may be not in the synthesis of foreign materials but in the uncoupling of the normal metabolic processes and controls. This could well explain the devastating effects on cellular structure of a limited virus synthesis.”

These conclusions severely undermine the idea that a tobacco mosaic “virus” is directly and causally responsible for the observed cell pathology. The absence of “virus” particles—paired with a proposed alternative explanation based on metabolic disruption—strongly suggests that the so-called “viral” damage is most likely, in fact, the result of the cell’s own collapse under stress.

In a 1967 follow-up study titled Some Conditions Affecting the Intracellular Arrangement and Concentration of Tobacco Mosaic Virus Particles in Local Lesions, Weintraub and Ragetli attempted to clarify their earlier findings by examining N. glutinosa leaves under different conditions using electron microscopy. Their results revealed that TMV-like particles were rarely observed in living, attached leaves: “packets of particles about 285 mµ long that resembled TMV particles were found, but only in five cells out of 96 examined.” These packets were “very small, consisting of about 25 particles in a single row,” and were only seen in totally necrotic cells—never in damaged but still-living ones. They admitted that “virus particles were never observed in the cells before necrotic changes occurred,” and that “no particles were observed in many clearly necrotic cells.” This contradicts the expectation that “virus” particles should be abundant prior to or during the onset of cell death if TMV is the direct cause.

In detached leaves at the same temperature (21°C), however, “at least one-half of the cells examined contained TMV particles,” often arranged in long rows or loose clusters near starch grains. At higher temperatures (26°C), particles remained mostly undetectable in attached leaves until the tissue was fully necrotic. In contrast, detached leaves at 26°C showed widespread accumulation of particles, often in crystalline arrays or vesicle-bound clusters. This stark difference suggests that the appearance of “viral” particles depends heavily on experimental conditions—including whether tissue is attached or detached and at what temperature it is kept. These findings raise the possibility that the presence of “virus-like” particles is a consequence of necrosis or cellular breakdown—not a cause. Weintraub and Ragetli themselves noted that “crystals of similar appearance have been observed in healthy N. glutinosa leaves exposed to high temperatures,” further undermining the idea that these structures are specific indicators of “pathogenic” activity.

This interpretation is further supported by standard references in the field. As Matthews’ Plant Virology acknowledges, “some normal structures in cells could be mistaken for virus-induced effects—for example, crystalline or membrane-bound inclusions in plastids.” It also notes that “nuclei of healthy cells sometimes contain crystalline structures that might be mistaken for viral inclusions.” Even the apparent cellular degeneration often cited as evidence of “viral” activity—such as “disorganization of membrane systems, presence of numerous osmiophilic granules, and disintegration of organelles”—is admitted to be “similar to normal degenerative processes associated with aging or degeneration induced by other agents.” These statements make clear that the visual markers of presumed “viral” activity are not unique to “viruses” at all, and may simply reflect nonspecific stress responses or normal variation within healthy cells.

This reveals how much of virology—even in the supposedly well-understood TMV system—relies more on interpretation than direct evidence. The belief that “viruses” cause such damage is preserved not through confirmation, but despite the absence of it. This calls into question the scientific rigor and foundational assumptions of the field.

The findings of Weintraub and Ragetli were anticipated in a 1958 paper by Thomas Shalla titled Relations of Tobacco Mosaic Virus and Barley Stripe Mosaic Virus to Their Host Cells As Revealed by Ultrathin Tissue-Sectioning for the Electron Microscope. In it, Shalla examined over 1,000 ultrathin sections of epidermal, mesophyll, and hair cells from mature and embryonic leaves of tobacco and tomato plants systemically “infected” with tobacco mosaic “virus.” Despite the systemic nature of the presumed “infection” and the presence of cytological degeneration in various cell types, Shalla failed to observe rod-shaped particles resembling TMV—except in cells containing crystalline inclusion bodies. Even in cells adjacent to necrotic lesions, which were assumed to be active sites of “virus” synthesis, no recognizable TMV particles were seen.

Because TMV particles were absent where they were expected, Shalla proposed that the “virus” must exist in a smaller or altered form during replication—different from the ~300 nm rod typically found in sap or inclusion bodies. This speculative, post hoc explanation was introduced to preserve the “virus” hypothesis in the face of contradictory evidence.

Rather than supporting the “virus” model, this paper inadvertently exposes a recurring problem in virology: the failure to directly observe “viruses” where they are presumed to act, followed by rationalizations instead of reevaluation. Shalla himself noted that multiple forms “related to TMV” appeared in “infected” plants, but with properties differing from the canonical 300 nm rod. TMV-like proteins were detected even in the absence of full “viral” structures, and preliminary claims were made about an “infective” RNA component in plant sap—yet these findings lacked direct correlation with intact particles. Even more troubling, other researchers reported that nucleic acid material in “infected” cells exhibited different ultraviolet absorption and ribonuclease sensitivity than the TMV model predicted, suggesting a mismatch between biochemical observations and the accepted “viral” structure. These contradictions reveal a deeper issue: what is presumed to be a coherent “viral” entity is, in practice, a patchwork of loosely connected and often conflicting data. The assertion that the active form of the “virus” is simply undetectable, coupled with reliance on indirect assays such as sap “infectivity” or tissue damage, leaves the replication hypothesis unsupported by direct evidence. What is presented as “virus replication” often rests on inferred outcomes, not observed mechanisms. This reveals that virology tends to sustain its foundational claims through interpretation rather than empirical verification.

Despite widespread claims that the tobacco mosaic "virus" was the first to be visualized and characterized through electron microscopy, the primary literature reveals a far more uncertain foundation. Researchers like Helmut Ruska, Mattern, Weintraub and Ragetli, and Shalla openly acknowledged the limitations of their observations, the speculative nature of their interpretations, and the lack of consistent correlation between particle presence and the lesions assumed to represent “viral” replication.

The assumption that the rod-shaped structures observed under electron microscopes were definitive evidence of “viral” particles rested not on direct experimental proof, but on analogies, heuristics, and prior expectations. Weintraub and Ragetli’s work is especially revealing: even with sophisticated imaging techniques and ultra-thin tissue sectioning protocols, they rarely detected TMV particles in attached, living “infected” leaves—finding them only in a handful of fully necrotic cells, and never in damaged but still-viable ones. Moreover, no particles were seen in many necrotic cells, and in detached leaves, particles appeared abundantly regardless of whether the tissue was necrotic or not. These findings—suggesting that the appearance of TMV particles may be a consequence of necrosis or tissue detachment, rather than its cause—directly undermined the visual narrative constructed by earlier EM work. Yet instead of provoking a serious re-evaluation of the “virus” hypothesis, the results were met with reinterpretation and rationalization designed to preserve it.

Taken together, the historical record shows that what has been presented as empirical confirmation of a “viral” agent was, in fact, inference built upon prior assumptions. This pattern—of presuming a “virus” at the outset and then interpreting ambiguous or inconsistent findings through that lens—calls into question the methodological rigor and falsifiability of foundational virological claims. At minimum, it demonstrates the need to critically reexamine what counts as evidence in the field.

In the case of tobacco mosaic “virus,” the absence of direct, replicable demonstration of “viral” particles in the very locations they are assumed to be most active undermines the core narrative of “virus” replication. What remains is not a settled matter of science, but a pseudoscientific hypothesis that has been protected through interpretive flexibility rather than rigorous confirmation.

The Tobacco Mosaic Crumbles

The foundation of the “virus” concept is built on failure—failures that have been reframed as progress. From the outset, virology has struggled to meet the standards of scientific inquiry: the inability to satisfy Koch’s logical framework, the absence of a consistently identifiable causative agent, the routine neglect of proper controls, the unwillingness to examine alternative causes, and the persistent use of circular, assumption-laden reasoning. These are not minor oversights or temporary gaps in understanding—they are fundamental flaws. The cracks in the “virus” mosaic are numerous, and they remain clearly visible to those willing to examine the scientific literature critically and logically.

The tobacco mosaic “virus” was not a breakthrough in understanding disease—it was a pivot point. It marked the transition from observation-based science to belief-based inference, from demonstrable cause-and-effect to models built on indirect signs and symbolic proxies. The “first virus” earned its title not by satisfying the demands of rigorous proof, but by becoming the first to be accepted without it. It was the prototype for a new kind of “science”—one in which contradictions are smoothed over, anomalies ignored, and missing evidence explained away through ever-changing speculation.

The consequences of this shift have been profound. An entire field was built on protecting an idea—that disease must come from an invading, invisible agent—rather than on empirical certainty. When direct evidence was missing or contradicted the hypothesis, it was not the hypothesis that was questioned—but reality that was reinterpreted. This is not science as method; it is science as mythology.

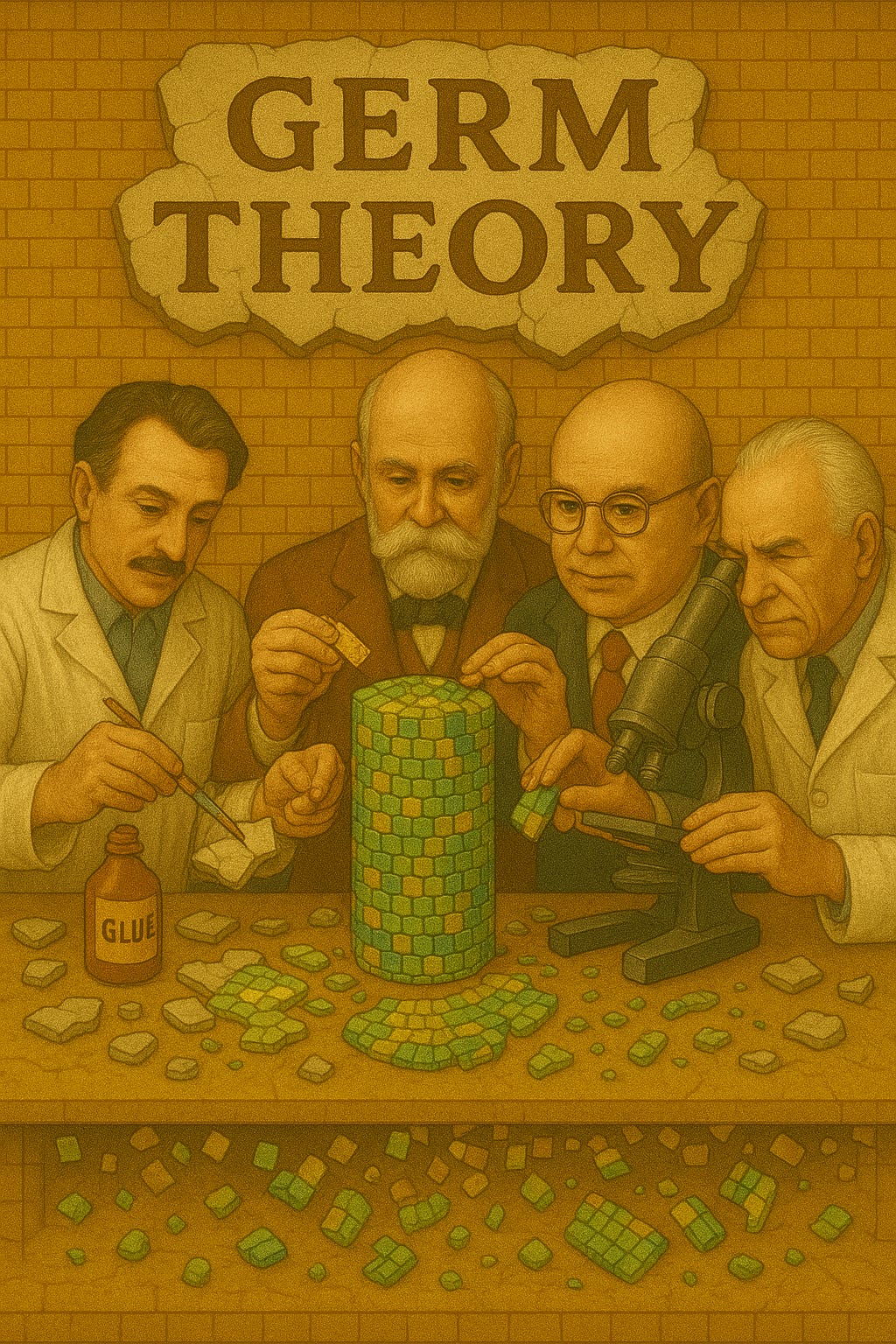

Mayer, Ivanovsky, Beijerinck, Stanley, and Ruska are heralded as the fathers of virology. But what they truly fathered was a narrative—a patchwork of assumptions, methodological shortcuts, and circular reasoning elevated to the status of scientific fact. In transforming the tobacco mosaic “virus” into a foundational myth, they ushered in an era where belief stood in for proof and where failure to demonstrate causation was reframed as evidence of something invisible. What they pioneered was not a discovery, but a deception: gluing together the crumbling pieces of the germ “theory” into the mosaic that became the tobacco mosaic “virus.”

was able to find the humor in the latest “pandemic” scam.The Baileys also delivered another strong Q&A session.

demolished the latest study erroneously claiming to put the vaccine/autism debate to bed. has an excellent expose on the connection between chickenpox and arsenic. added some much needed critical thinking and logic to recent E. coli scares. provided an excellent interview with Dr. Tim Cowan.There was also an excellent break-down of the spike protein deception.

examined Pasteur's anthrax disaster. presented an amusing long-lost Sherlock Holmes tale.

Thank you, Mike. Job well done.

Project Veritas Psyop used to push contagion theory & anal swabs https://nuremberg2.substack.com/p/project-veritas-psyop-used-to-push-contagion-theory-anal-swabs