Syphilis is a disease that I had never given much thought about for the majority of my life. I was born at a time when syphilis was moved aside as the big bad sexually transmitted disease in order to make room for its successor to the throne in HIV. Growing up, we were never really taught much about syphilis in school or at home as it seemed to be relegated as a relic of the past. Instead, we were bombarded by horror stories of the terrifying death that awaited anyone unlucky enough to be diagnosed with HIV. We were taught to fear blood, needles, and drug use, concepts much easier for children to grasp over sexual intercourse. Thus, when I found out that a family member of mine had been diagnosed with syphilis in the past, I didn't know what to make of it other than it didn't seem as terrifying to me as HIV. The news about this past diagnosis did not provoke much of a reaction in me at all.

Eventually, my relative, who had not suffered any symptoms for decades, was told to get a series of three penicillin injections in order to cure a “latent infection.” Even though we were hesitant about the use of antibiotics, we accepted the decision as we were told that, even though there were no symptoms presently, the bacteria could resctivate at any time, leading to severe neurological complications, blindness and ultimately death. It was decided that it was best for this person to finally be rid of this label that they had been burdened with for decades.

However, the promised “cure” was nowhere to be found. After completing the series of injections, my relative became ill with flu-like symptoms. Over a few weeks’ time, this led to rapid weight loss, a fever, severe cough, fatigue, and extreme sweating. While these are somewhat generic symptoms, they are commonly associated with syphilis, as noted by the CDC:

In addition to rashes, signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis may include:

fever

swollen lymph nodes

sore throat

patchy hair loss

headaches

weight loss

muscle aches

fatigue

https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis-detailed.htm

Upon returning to the doctor's office, instead of admitting that the injections were unsuccessful and were actually harmful, my relative was diagnosed with HIV, a “virus” that was tested for prior to the penicillin injections which had come back negative. Thus, we were led to believe that my relative, in the span of about 6-8 weeks, had syphilis but not HIV, was cured of the syphilis through the 3 penicillin injections, and then somehow acquired HIV within that timeframe leading to the exact same symptoms assigned to syphilis as well as side effects of the penicillin injections themselves. Not only that, we were also told that it was full blown AIDS at this point. Knowing this person's history, we knew HIV was an impossibility, and we knew, according to their own narrative, acquiring AIDS that quickly was an impossibility as well. Thus, we demanded further testing to find out the “true” cause of disease. The hospital eventually agreed and ultimately decided on a diagnosis of tuberculosis, which resulted in 9 months of additional toxic antibiotic overload to treat the symptoms of disease brought about by the first round of toxic antibiotics, eventually leading to a long, drawn-out death for my relative. Little did I know at the time as to how intimately connected these diseases are to one another. I believe that, upon exploring syphilis, known throughout history as “the great imitator,” it will become clear that these diseases have far more in common than people realize.

Syphilis is a huge topic and one I've been meaning to explore more in-depth for quite some time. It is personal and a bit painful for me as the diagnosis and treatment for this disease was the beginning of a long nightmare for my family. However, as there is much that encompasses the history of the disease, it is very difficult to distill the syphilis scam down into just one article. Thus, I am doing a series on this so-called bacterial disease in order to hopefully do the topic some justice. In this article, my intent is to provide a brief history on the disease and examine the discovery of the syphilis bacterium. We need to ask ourselves if the association of a bacterium with those suffering certain symptoms is enough to prove causation. Did the discovery of the Treponema pallidum satisfy the logical requirements of Koch's Postulates in order to prove the bacterium as the cause of disease? Were there any other microbes found that could have potentially been the “pathogen?” Was T. Pallidum even a new bacterium that was morphologically distinguishable from previous bacterial discoveries? Was it unanimous that T. pallidum was the etiological agent or was this a decision by those in a position of power and influence? Let's explore these questions and see what we can uncover.

The Origins Of Syphilis

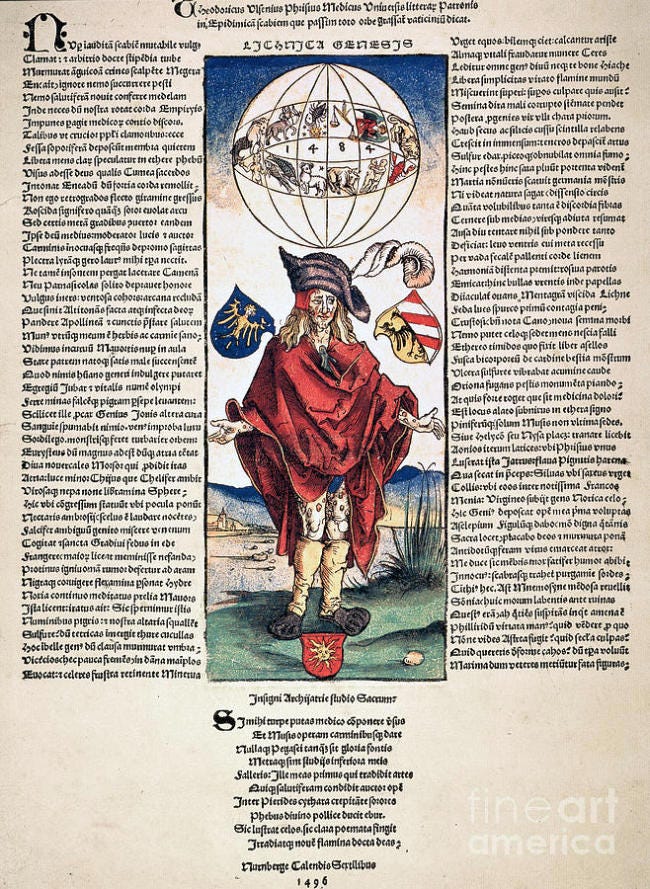

While there are many hypotheses about the origin of the disease known as syphilis, it appears that the first distinction of there being a new disease was based upon the woodblock drawing of a German artist named Albrecht Dürer in 1496. The drawing was accompanied by text from physician Theodorus Ulsenius warning of a new disease, where he supposedly described the signs and symptoms and stated that these were in relation to the great astrological conjunction of 1484. While the disease was said not to be curable, drinking the water from the river Jordan was prescribed, calling upon stories of curing leprosy in such a manner:

Syphilis in art: an entertainment in four parts. Part 1

“An example of Durer's work accompanied a broadsheet issued to the public on 1st day of August 1496. The broadsheet was written by the Nuremberg physician, Theodorus Ulsenius. The first edition, but not the second, was dated (fig 7). In it Ulsenius apologises for his, a doctor's excursion into poetry. He warns about the new disease that is sweeping the country, describes its signs and symptoms, says it cannot be cured and purports to establish a direct connection between the epidemic and the great astrological conjunction of 1484. Note this date on the globe with the signs of the Zodiac. The decastich, a poetic footnote by Ulsenius, admonishes the reader to keep calm and advises any victim of the disease to drink the waters of Jordan, presumably a reference to 1 Kings, 5, 14, where Haaman is cured of leprosy by dipping himself seven times in the river Jordan.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1194440/

It is said that this depiction attributed to Dürer was inspired by an outbreak of lesions which occurred amongst the soldiers fighting for France against Italy in 1495. How a supposed sexually transmitted disease broke out amongst the men at war was not described, nor do we really need the details. The symptoms were likened to leprosy and were described by Ulsenious as boils, ulcers, and crusts with the astrological conjunction of 1484 deemed as the cause presented to him in a dream by the Sun god Apollo. Interestingly, the disease was later often referred to as the Great Pox in order to distinguish it from smallpox, which was seen as a less severe version:

“In 1495, a wretched new disease emerged among mercenary soldiers fighting in the armies of Charles VIII, King of France, on the battlegrounds of the First Italian Wars (1494–1498).[11] The first sign was a small, often painless, genital lesion that spread into a rash of pustules across the body. The sores subsided and then returned, often escalating into cavitating lesions that disfigured victims; its effects could be fatal. A Venetian physician, Alexandri Benedetto, compared their misery to the most infamous biblical disease: ‘The entire body is repulsive to look at, and the suffering is so great…that this sickness is even more horrifying than incurable leprosy…’ (Benedetto, 1497, in Quétel, 1990, p 10). Like the biblical accounts of lepers who suffered before them, victims of the epidemic became social outcasts (Quétel, 1990, p 23). Their putrefying wounds produced a ‘loathsome secretion making such a stink’ that it was feared as a source of contagion (Ulrich von Hutten, 1519, in Quétel, 1990, p 28).[12] Initially called the French disease (Mal Francese, Morbus Gallicus, Franzosenkrankheit) because of its early association with the soldiers of a French king, or the ‘Great Pox’ in vernacular English, it has been broadly accepted that the epidemic was a more virulent strain of the bacterial disease known in contemporary medicine as syphilis (Sudhoff, 1925, IX; Quétel, 1990, 3; Panofsky, 1961, p 3).[13]”

“While the subject of this section – the remarkable Vaticinium in Epidemicam Scabiem by Theodorus Ulsenius – was related to these Syphilisblätter in terms of its mode of production and communicative function, its imagery contrasted the overtly Christian themes of its contemporaries. Rather than attributing the outbreak to God’s direct intervention, the epidemic was ascribed to astrological causes. Two columns of Latin verse by Ulsenius attribute the arrival of the ‘boils, ulcers and crusts’ of the Great Pox to the so-called Great Conjunction of 1484, an astrological event in which ‘no less than five planets, all except Venus and Luna, met in the Sign of Scorpion’ (Ulsenius quoted in Panofsky, 1961, pp 5 and 14). This conjunction was revealed to Ulsenius in a dream by Apollo – Greco-Roman god of truth, prophecy, healing and the Sun, among other attributes. Regrettably, Ulsenius woke before Apollo could divulge a cure.”

It was also around this same time when Christopher Columbus was exploring the America's and was said to have given the Native American's both influenza and smallpox by interacting with them. This exchange supposedly led to Columbus and his crew bringing home the great pox, rather than the small pox, back to Europe with them in 1493. It is claimed that it was from the return of this expedition that the disease quickly spread throughout Europe. The disease was eventually given the name syphilis by 16th century poet Girolamo Fracastoro, who, like Ulsenius, also wrote of a vengeful sun god, who struck down the mythical shepherd Syphilis with disease. While the name syphilis eventually stuck, these same symptoms were classified under many names throughout the centuries, mostly based on geographical locations and/or attributed to a given population as the cause:

THE GREAT POX

“Columbus’s exploration of this new world was no exception. Shortly after his crew's arrival, the indigenous population was decimated by epidemics of influenza and smallpox that swept across the continent. The evidence suggests that this was a mutual disease exchange; by 1495, Columbus and his crew arrived back in Europe and they brought the ‘Great Pox’ (as opposed to the ‘Small Pox’) with them. This ‘Great Pox’ soon gained notoriety because of the severity and location of its physical symptoms:

“boils that stood out like acorns, from whence issued such filthy stinking matter that who so ever came within the scent, believed himself infected” [Von Hutten (1519), translation from Major (1945) p31(5)].

Today we know this disease as syphilis thanks to Girolamo Fracastoro, the famous 16th century mathematician, physician and poet from Verona, who described a dreadful plague sent by a vengeful sun god to strike down the mythical shepherd Syphilis in his poem Syphilis sive morbus gallicus. This name has stuck to this day.”

“These names had one thing in common – an inherent desire to attribute this terrible disease to foreigners and aliens. The French named it the ‘Neapolitan disease’, the Russians the ‘Polish disease’, the Polish and the Persians called it the ‘Turkish disease’, and the Turkish called it the ‘Christian disease’. Further afield, the Tahitians named it the ‘British disease’ and in Japan it was known as the ‘Chinese pox’.

Thus, we have a hypothesis that Columbus brought a new disease, which consisted of ulcers, boils, and crusts reminiscent of leprosy, from the Americas to Europe. However, was this really a new disease as depicted by Dürer and Ulsenius in the uncovered woodblock from 1496, or is this yet another case of mistaken identity? As is often the case with many of these diseases, both leprosy and syphilis (along with tuberculosis) were commonly confused with one another as well as many other conditions involving flu-like symptoms and eruptions of the skin:

Leprosy: A nearly forgotten malady

“For centuries leprosy was feared because of its contagious nature (though this was exaggerated) and the disfigurement it caused. It was believed to be highly contagious and was treated with mercury—as was syphilis. Many cases thought to be leprosy were confused with syphilis and tuberculosis. The diseases commonly coexisted.”

https://hekint.org/2017/12/29/leprosy-nearly-forgotten-malady/

Even based on serological tests, there is cross-reactivity between leprosy and syphilis as demonstrated by this WHO study in 1953:

A Study on the Behavior of Leprosy in Serological Tests for Syphilis

“The extent to which leprosy interferes with the routine serological test for syphilis has been variously reported by different workers. It has been observed that different test techniques show different percentages of positive reactions.”

“The sera obtained from leprosy patients in general, and particularly from those with the lepromatous type of leprosy, give rise to many biologically false positive reactions in serological tests for syphilis, probably because the quality of the lipoids, liberated by the breakdown of lepra bacilli, is somewhat similar in its antigenic nature to that of heart extract.”

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/265831

This means that even using supposedly specific immunological markers, many times these two diseases cannot be distinguished from one another. Thus, it appears that we have yet another instance where the same symptoms of disease were rebranded and reclassified as separate diseases that were then assumed to be caused by different pathogens. This makes sense when the symptoms are viewed on a continuum of progressing stages of the same detoxification process. These symptoms can start from a relatively benign state and progressively get worse based on the terrain of the individual and the treatments employed:

sniffles, sneezes, cough, and congestion >

fever, sweats, chills, skin eruptions, swollen lymph nodes >

vomiting, diarrhea, bleeding >

trouble breathing, neurological symptoms, cancer, and death

These symptoms are all varying stages of the same dis-ease process that is brought about by the body attempting to detoxify and heal itself.

Of course, the conditions that the individuals are in who are experiencing these symptoms as well as their environment is rarely examined as potential causes for any state of dis-ease. Was it taken into consideration what effects that the long voyage at sea without adequate food supplies, unsanitary living conditions, and the stress of travelling to a new world had on the health of Columbus's crew? How about the effects that stress and the ravages of war combined with being surrounded by death, destruction, and unsanitary conditions had on the French army? These factors are rarely taken into consideration. The invisible microbe is to blame, and a treatment is needed in order to heal the body that is seen as incapable of healing itself.

While the etiological cause of syphilis remained a mystery for centuries, this did not stop the physicians of the day from resorting to toxic treatments in order to '“cure” their patients. There were two popular methods which were most commonly used for the treatment of this “new disease.” The first consisted of the wood of an Evergreen known as “holy wood” which was made into a steaming hot drink meant to help the patient sweat the toxins out. The second was a mercury cream that was rubbed onto the patient in hopes that the resulting toxicity would cause them to become diuretic and salivate enough to excrete the syphilis toxins out from within. This approach was also used for leprosy at the time as mercury was seen as a solvent of sorts for skin eruptions. Sadly, many succumbed to mercury poisoning. A third, and less common approach, was to go to a bathhouse in order to sweat out the toxins. As can be seen, in all cases, the idea was to help expel toxins from the body. Interestingly, the less toxic “holy wood” remedy was reserved for the wealthy while the highly toxic mercury was given to the poor:

“After mercury, the second most popular remedy against syphilis was guaiac or “Holy Wood.” It was a substance obtained from evergreen trees indigenous to South America and the West Indies, becoming the remedy for wealthy patients while mercury was administered to the poor.”

“There are itching sensations and an unpleasant pain in the joints. The skin is inflamed with revolting scabs and is covered in swellings and tubercules, which are of a livid red color at first and then become blacker. It most often begins with the private parts. Nothing could be more serious than this curse, this barbarian poison.”

-Italian doctor Nicolò Squillaci wrote in a letter dated 1495

The Discovery of T. Pallidum

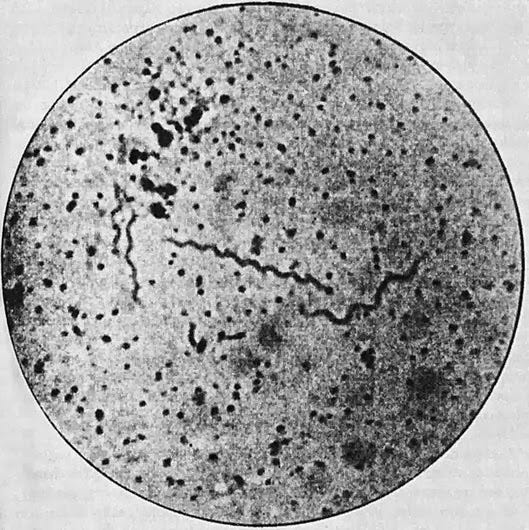

While the cause of syphilis was assumed for centuries to be a poison in need of being purged from within the body, it wasn't until the early 1900's, with the sudden boom in finding bacterial causes of disease, that the presumed bacterial cause of syphilis was identified. This outside invader was discovered in 1905 by German zoologist Fritz Schaudinn and dermatologist Erich Hoffmann. According to the 1914 edition of the Textbook of Skin and Venereal Diseases, the bacterium was found after smear preparations from spleen juice obtained via puncture. These spirochetes were said to eventually be identified in the organs assumed to be afflicted by the disease as well as in the blood and organ juices. The fact that the spirochaetes were supposedly seen in such high numbers was taken as proof that this bacterium was the cause of the disease:

Textbook of Skin and Venereal Diseases

“The assumption, voiced by all of us long ago based on the nature of the course of the disease and in analogy with other diseases, tuberculosis, leprosy, snot, that the poison of syphilis must be an organized poison, has finally become tangible truth — that of SCHAUDINN when working together discovered Spirochaeta with E. HOFFMANK on March 3, 1905. pallid a is the causative agent of syphilis. Spirochaeta pallida was first found in smear preparations from primary lesions, weeping papules, in the lymph gland juice. detected in the spleen juice obtained by puncture. This was soon followed by the detection of the microorganism in closed syphilitic efflorescences that were far removed from the site of infection, licking roseola, papules, and also the detection of masses of spirochetes in congenital syphilis in the efflorescences and all internal organs. The naturally very important postulate with regard to the etiological significance, the detection of the spirochetes in the flowing blood, was also fulfilled in a flawless manner. While the findings mentioned so far refer to investigations of secretions or organ juice in the living state or in the dry preparation, a very important advance was made by the method discovered by E. BERTARELLI and VOLPINO, by means of silver impregnation, to represent the spirochetes in the section preparation. In rapid succession, the spirochetes were detected in papules, primary lesions, lymph glands and in congenital syphilis in all internal organs in acquired syphilis in such numbers that any remaining doubts as to the etiological significance of this microorganism were bound to be silenced. The relationship of the spirochetes to the disease processes in the tissue, which was already demonstrated in the early days, is proof of the etiological significance. At the edge of the infiltrates, just where the disease process is advancing, there is the most plentiful accumulation of spirochetes, while in the inner parts of the infiltration they tend to be more sparse. The spirochetes are particularly found in the lymphatic spaces, between the connective tissue fibrils, in the walls of the lymphatic vessels and veins, and in the interepithelial gaps.”

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-99262-9_122

For a little more insight into what was done to discover this bacterium, I have translated the method section from the 1905 report by Schaudinn and Hoffmann. It was immediately stated that there were many negative results in finding the bacterium in syphilitic patients. However, this was chalked up to the incorrect removal of the material being studied. While they maintained that the spirochetes could be found in the fluids of chancres and pustules, it apparently mattered in how the samples were made in order to get the results that they desired. The researchers felt that simple secretion preparations were the least suitable, primarily because they usually contained only sparse or no spirochetes, and instead, there were all kinds of different bacteria and other spirochete species in large numbers in the preparations. Cleaning the preparations with physiological saline solution was done to get rid of many of these microorganisms. It is unclear how the two researchers determined that the discarded microorganisms were not the causative agents that they were looking for. They claimed that the best material to find these spirochetes in was within the pemphigus blisters in newborns as well as pustular lesions in adults which was obtained by scraping off some tissue fluid from the bottom of the opened blister. Tissues used for examination were usually fixed with formalin, but alcohol could also utilized instead. Tissues which were fixed for years were also considered acceptable. The researchers used Eosinazu stain in order to stain the spirochetes to a red color which was said to be beneficial for differential diagnosis. In other words, if the spirochetes were red, they were the syphilis bacterium. If they did not stain red (or any of the alternative colors eventually used for staining purposes), the bacteria were presumably something else:

The Etiology of Syphilis

“The correct removal of the material is of decisive importance for the success of the examination in the fresh state and in the stained smear; In addition to a lack of practice and perseverance, mistakes in this direction are primarily responsible for the multiple negative results of some authors. Spirochaeta pallida is usually found most abundantly in the tissue juice obtained by squeezing excised primary lesions and papules 3 ) . This type of U, which Schaudinn and I first chose with good reason.

However, research can only be carried out in a few cases and is not suitable for practice; however, it is not necessary either, since under certain conditions the spirochetes can be found almost constantly in the secretion of chancres and papules. As I first showed and had Mulzer examine more closely, one can either use the surface secretion or the stimulating serum that oozes out after prolonged rubbing, or finally the events obtained by scratching with a platinum spatula or spoon and those obtained in this way. Compare secretion, irritation serum and scraping preparations with one another with regard to their Spirochaetae pallidae content. Simple secretion preparations proved to be the least suitable, because they usually contain only sparse or even no Spirochaetae palhdae, but on the other hand all kinds of bacteria and sometimes also other spirochete species in large numbers. The stimulus serum technique yields very good results 1) if the surface of an eroded primary affection or a papule is rubbed with a platinum loop, copious amounts of serum 2 ) usually swell out after a short time, which is very well suited both for fresh examination and for the preparation of thin smears. By scratching with a platinum spatula one often obtains material to be examined (events) that is even richer in spirochetes, especially if one sticks to the periphery of erosion. Thorough cleaning of the papules and chancres with a physiological saline solution is usually sufficient to completely or largely eliminate the different types of microorganisms parasitizing on the surface. Sclerosis and papules that have already been treated with calomel, iodoform, or another antiseptic must be thoroughly washed and usually bandaged with sterile MuU or physiological saline for 1 to 2 days before the examination can be carried out with any prospect of success. Remove from closed efflorescences.

Carefully cut the horny layer with a scalpel, avoiding bleeding as much as possible, and then try to extract tissue fluid from the rete and the papillary layer. For tertiary exanthema and gums must be removed from the edge zone. The best material is obtained from pemphigus blisters in newborns and pustular lesions in adults by scraping or scraping off some tissue fluid from the bottom of the opened blister. Glands are punctured according to the prescription I have given; With the tip of the needle one first tries to reach the cortical layer on the convexity of the gland punctured in the longitudinal diameter and aspirates vigorously while gradually withdrawing the syringe. The examination of the blood is most promising if one punctures the congested cubital vein. In the case of internal organs, a fresh cut is made and, after the blood has been dabbed off, some tissue juice is removed, if possible from the edge of visible disease foci. For examining the spirochetes in section, the organs etc. are best fixed in 10 percent formalin solution (formalin 1.0 distilled water 9.0) and leave it there until processing; Bertarelli and Volpino recommend alcohol instead. Pieces that have been in the fixing liquid for years can still be impregnated. Practiced observers with a keen eye are advised to carry out a fresh examination as the simplest and fastest method. This method has proven itself to me and my co-workers particularly for papule and sclerosis secretion 1 ), whose spirochete content is to be checked quickly before being used in the animal experiment; Diluting the starting material with a little physiological (0.85 percent) saline often proved to be expedient. A good Apochromat 2 ) (I use Zeiss 2mm, 1.3 or 1.4 alert) and Konipensations eyepiece 6 to 12 are essential for this examination, bright illumination with Auerlicht and correct deflection by lowering the condenser is recommended. Instead of the hanging drop, for the fresh examination not only of the Syphilis spirochete, but also of other species, I choose the simple coverslip preparation framed with vaseline, in which these microorganisms, as my student Beer and I have shown, remain mobile for weeks in the absence of air so that it is extraordinarily suitable for the continuous study of the movements and the influence of reagents, immune serum, etc. Smear preparations can be made on coverslips or slides 1 ); the thinner they are, the more the delicate spirochetes appear after the coloring. According to our initial information, the fixation usually takes place in absolute alcohol. 10 minutes long; it is not necessary, however, and the air-dried preparations can be stained without further ado, if necessary after carefully drawing them through the flame. As Halle and I have shown, when using Weidenreich's method — prior osmation 2 ) of the slide and the resulting momentary fixation — thicker smears can also be used, in which the larger number of spirochetes naturally makes it much easier to find them . Among the numerous stains recommended over time, the Eosinazu stain first tested by Schaudinn and myself, in the form later sharply specified by Giemsa himself, has so far claimed first place and is in fact not surpassed by any newer method; in 3/4 to 1 hour there is a clear, characteristic red coloration of the syphilis spirochete, which is not unimportant in terms of differential diagnosis. Röna-Preis and Berger recommended modifications which produce sufficient coloring after only a few minutes of heating. Marino blue or hot gentian violet solution (Herxheimer) are also useful and have been used with good success by a number of authors x ) More recommended for clinical purposes. 2) Instead of osmic acid, the cheaper formalin can also be chosen.

In very thin, low-protein smears - possibly mixed with physiological saline solution - Löffler's flagella staining gives excellent results and at the same time the best representation of the "flagellas" discovered by Schaudinn Volpino's method, which corresponds roughly to v. Ermenghem's scourge staining, is not very recommendable because it is too uncertain and precipitates easily, although it gives excellent results in the hands of Bertarelli and some other authors, as I know from my own experience, gives excellent results. The most popular is the modification of Ramon-y-Cajal's method tested by Levaditi, which is excellent for the internal organs in particular, but also for the skin. Pieces of skin (primary lesions, papules, etc.) and glands are, in my experience, better treated by the second argentum-pyridine method discovered by Levaditi and Manouelian, since the tissue fibers do not become so dark brown and the spirochetes also become more tender impregnate and allow details of the structure to be seen better. Restaining of the sections is not necessary, but can be done very well and is advisable for studying intracellular storage; Of all the solutions mentioned, the most recommendable seems to me to be Unnasche's polychrome methylene blue, which, if correctly differentiated with glycerol ether, also shows the numerous plasma cells in the syphilitic growths alongside the spirochetes. For a more detailed study of the relationship between the spirochetes and the individual tissue components, Verse's suggestion that some of the successive sections in the series should be completely desilvered with a concentrated solution of sodium thiosulphate and then treated with the usual tissue stains deserves attention. I have to confine myself to this brief list of the most important methods, while referring to the appendix for a more detailed description, and now I will go on to present the test results.”

https://archive.org/details/dietiologieder00hoff

Satisfying Koch's Postulates?

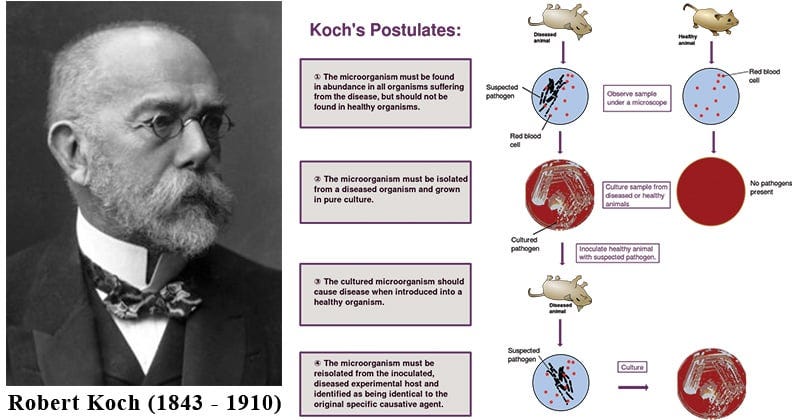

One must ask if finding spirochetes in those claimed to be syphilis patients is indeed enough evidence in order to claim a certain microbe is the causative agent of disease. If we are to hold these researchers to the accepted logical standards for proving microbes as pathogens capable of causing disease as established by Robert Koch in 1890, finding the spirochetes is only part one of the process:

The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms suffering from the disease but should not be found in healthy organisms.

The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture.

The cultured microorganism should cause the same disease when introduced into a healthy organism.

The microorganism must be reisolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

The act of finding a bacterium in a sick individual is not, in and of itself, conclusive evidence of causality as correlation does not equal causation. The other steps of Koch's Postulates must be satisfied before the microbe can be designated as the causative agent. With that in mind, let’s see how T. pallidum stacks up with Koch’s Postulates.

1. The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms suffering from the disease but should not be found in healthy organisms.

According to Koch's first Postulate, the presumed pathogenic microbe should be found in abundance in every person afflicted with the disease. This makes sense logically according to their narrative as there should be millions, if not billions, of these specific microorganisms within the body at the time of illness if they are to be able to overload the “immune” system in order to cause disease. Koch also stated that the microbe must not be found within the healthy as, if it is, this would show that the microbe was not the cause disease.

Regarding Schaudinn and Hoffman's T. pallidum, we have a few issues when trying to fulfill this first Postulate. At the same time that their discovery was announced, another German zoologist, by the name of John Siegel, found a different bacterium named Cytorrhyctes luis. This bacterium was also claimed to be the causative agent of syphilis. There was quite a bit of debate at the time between the researchers and their two discoveries, and it even caused the president of the Berlin Medical Society enough embarrassment over the matter to the point where he closed a session by stating: "the session is closed until a new etiologic agent is found for syphilis.” In other words, neither bacterium world be accepted as the etiological cause of syphilis and it was announced that another causative agent would need to be found in order for future sessions to proceed. However, within 6 months, it was ultimately decided by a majority that Siegel's findings were invalid due to various other researchers finding Schaudinn and Hoffman's spirochete:

“In 1905 two different etiologic agents for syphilis were proposed in Berlin, one, the Cytorrhyctes luis, by John Siegel, the other, Spirochaete pallida, by Fritz Schaudinn. Both scientists were pupils of Franz Eilhard Schulze, and were outsiders to the Berlin medical establishment. Both belonged to the same thought collective, used the same thought style, and started from the same supposition that the etiologic agent of syphilis must be a protist. Both used the same morphological approach, the same microscopes and the same stains. Both presented their findings in the same societies, used the same rhetoric, published in the same journals, used the same arguments to criticise each other’s shortcomings. Both were backed by powerful institutions and enlisted the support of prestigious patrons. Within half a year, the scientific community at large had in its overwhelming majority accepted Schaudinn’s results and rejected those of Siegel. Social forces thus cannot be shown to have played any role in deciding the issue.”

https://coek.info/pdf-siegel-schaudinn-fleck-and-the-etiology-of-syphilis-.html

We can see this conundrum of competing bacterium backed up in the 1997 book Spirochaetes, Serology, and Salvarsan: Ludwik Fleck and the construction of medical knowledge about syphilis which sheds further light on the presumed finding of the etiological cause of syphilis. While it became the accepted cause of syphilis, the discovery of T. pallidum was not the final proof necessary in order to determine the etiological cause of syphilis as there was much important information missing in regard to pathology, microbiology, and epidemiology. The author noted that, in the history of medical science, it was normal for a disease to be redefined in terms of the specific cause that was discovered. An example with tuberculosis was provided whereas, after the Mycobacterium tuberculosis was accepted as the causative agent of tuberculosis, any diseased state where the bacterium was found was considered a tuberculosis case. In other words, no matter what symptoms were being experienced, if the bacterium was found, the disease and the associated symptoms were officially tuberculosis. Similarly, if the bacterium was not found even though the clinical picture was clearly that of tuberculosis (or insert any other disease in this example), then it was not a case of tuberculosis and must be considered as something else entirely.

The author noted that the fulfillment of Koch's Postulates must be met in order for a pathogen to be considered the causative agent and for the redefinition of the disease to line up with the cases associated with the causative agent. The author reiterated that Schaudinn and Hoffmann's findings were met with extreme skepticism when they were announced due to the discovery of Siegel's alternative causative agent. However, because many others observed spirochetes in syphilitic cases, it was decided that Schaudinn and Hoffman would win the day, even though the recreation of the disease through pure culture had not been achieved (more on this later). Thus, it is clear that T. pallidum was not able to fulfill the remaining Koch postulates at the time it was accepted as the causative agent, and it was stated that this definitive proof would never come. All the scientific community had was correlation equaling causation as it was assumed that, because many researchers observed the same spirochetes in cases of the disease, it was the etiological agent. Even then, the same spirochetes were seen in other diseases such as yaws, as noted also in 1905, with the discovery of Spirochaeta pertenuis by Aldo Castellani. This spirochete was said to be indistinguishable from T. pallidum. Thus, the spirochetes were not specific to a certain disease, which violates the laws of specificity of the causative agents of disease:

Spirochaetes Serology And Salvarsan

“As an example he refers to the acceptance by the medical community of Fritz Schaudinn's Spirochaeta pallida and its rejection of John Siegel's Cytorrhyctes luis as the aetiological agent of syphilis (100/131).”

The 'aetiological' concept of syphilis

The 'aetiological' concept of syphilis became established with the discovery in 1905 of the causative agent, Spirochaeta pallida (now Treponema pallidum), by Fritz Schaudinn and Erich Hoffmann. As Fleck rightly points out, this achievement does not constitute the final consummation of the development of the modern concept of syphilis as a specific disease, because such a process is "incomplete in principle, involved as it is in subsequent discoveries and new features of pathology, microbiology, and epidemiology" (19/28). In the next chapter I will deal in detail with the discovery and subsequent acceptance of the pale spirochaete as the aetiological agent of syphilis. Here I will use the example of syphilis to discuss a fundamental question that is often raised in the philosophy of medicine: How should diseases be defined? Can they be defined by their 'causes' or, in the case of infectious diseases, by their 'aetiological agents'? The case of syphilis presents some interesting complications which may shed a new light on this philosophical problem and stimulate further reflection. Discussion of these complications will also provide a suitable occasion for broaching the vexed question of the essentially venereal character of syphilis and for examining alternatives to the prevalent 'venereal fixation'.

In the history of medical science it is a quite normal occurrence that a particular disease, after its cause has been identified, will become redefined precisely in terms of that specific cause. A case in point is the redefinition of tuberculosis. Already in 1883, only one year after Koch's discovery of the tubercle bacillus, Adolf Strümpell wrote in the first edition of his well-known Lehrbuch der speciellen Pathologie und Therapie: "The definition of tuberculosis is no longer based on any outward anatomical characteristic. Any disease which is caused by the pathogenic action of a specific species of bacterium, the tubercle bacillus discovered by Koch, is considered tuberculous". This redefinition raises a problem, because it would seem to transform the prima facie informative statement that tuberculosis is caused by the tubercle bacillus into a mere tautology. The problem has been highlighted by the Danish physician and philosopher Henrik Wulff in a comment on the position taken by the Australian philosopher J.L. Mackie. In a seminal article on causes and conditions, Mackie used the example of yellow fever:

"[...] we may say that the yellow fever virus is the cause of yellow fever. (This statement is not, as it might appear to be, tautologous, for the yellow fever virus and the disease itself can be independently specified)".

Not so, replies Wulff:

"I think that he is wrong on this point. There are mild cases of infection with yellow fever virus which no clinician could recognize clinically with certainty, but we should still say that the patient suffered from yellow fever, if we succeeded in isolating the virus from a blood sample. Similarly we can imagine clinical pictures, which are indistinguishable from typical yellow fever, but we would not say that such patients suffered from yellow fever, if some other infective agent was isolated. Yellow fever has been redefined to mean yellow fever virus infection [emphasis added]."

Wulff holds that this case can be generalized and that causal factors are never (or very rarely) necessary in relation to a disease entity except by definition.

Although I agree with Wulff that redefinition of diseases in terms of presumed causes is what normally happens in medicine (the above example of tuberculosis is just another illustration), I would like to amend his position in order to avoid some of its unpleasant consequences. Is it really no more than a tautology to state that yellow fever is caused by the yellow fever virus, tuberculosis by the tubercle bacillus, or syphilis by the pale spirochaete?

It must be stressed that the introduction of an aetiological definition of a certain disease entity does not occur at point zero of historical development. As a purportedly stipulative definition it is not a free choice independent of all preceding history, as Fleck would also emphasize. It often presupposes a prior definition of the disease entity in clinical or other non-aetiological terms. In order to clarify a point of principle we can divide, somewhat artificially, the period following the discovery of a candidate microbial agent of a particular disease into two stages. In the first stage the relevant scientific community will have to reach a decision whether it will accept the proposed microbe as the aetiological agent responsible for the disease. Ideally, the community will be guided in this decision by the methodological rules for establishing causality laid down by Robert Koch and known as Koch's postulates. To be meaningful at all, these rules presuppose that the candidate agent and the disease itself can be, to use Mackie's words, "independently specified". Of course, in practice the application of these rules is not always simple and straightforward. Sometimes circularity cannot be completely avoided. Let us suppose, however, that these difficulties have been adequately dealt with and that the microbial candidate Y applying for the vacancy of 'aetiological agent of disease X' has passed Koch's severe test with flying colours. At that moment we would have good reasons to assert "Disease X is caused by microbe Y" without thereby uttering an empty tautology. Now the second stage sets in and disease X will be redefined as 'the disease that is caused by microbe Y'. This means that the relevant scientific community will treat the proposition "Disease X is caused by microbe Y" from then on effectively as an analytic statement. It is to be left in place, come what may. Apparently contrary phenomena, such as those alluded to by Wulff, have to be assimilated by making adjustments elsewhere in the conceptual fabric. Perhaps they can be addressed by introducing Nicolle's notion of infection apparente (cf. Fleck: 18/27), or by splitting off a new disease entity called pseudo-X or para-X. Such at least is the solution the finitist or network theory would suggest for the problem of tautology or analyticity which engaged the philosophers Mackie and Wulff. It will be clear that the finitist viewpoint represents an intermediate position between the views of both.”

“After this philosophical excursion it is time to return to the historical case of syphilis. What were the consequences for the concept of syphilis when in May 1905 Schaudinn and Hoffmann proclaimed to the German medical world that they had identified a pale spirochaete, Spirochata pallida, as the probable causative agent of the disease?

Initially, their announcement met with extreme skepticism. The pale spirochaete also had to contend with a rival pretender for the title of aetiological agent of syphilis, John Siegel's Cytorrhyctes luis, which was supported by eminent protozoologists. According to an official German report released on 12 August 1905, however, spirochaetes had already been found "by more than a hundred authors in the most diverse products of syphilis" (16/25). This large number of confirmations tipped the balance in favour of Spirochaeta pallida. On 18 January 1906, Germany's foremost dermatologist and venereologist, Albert Neisser, declared that Schaudinn's spirochaete was "in all likelihood" (mitgrdsster Wahrscheinlichkeit) the aetiological agent of syphilis, "although the compelling proof: 'experimental production of the disease through pure cultures', has not yet been provided". This 'compelling proof would never be produced. The spirochaete stubbornly resisted any attempt at pure culture. Koch's postulates could therefore not be fully satisfied. Even in the absence of this crowning piece of evidence, Spirochaeta pallida was accepted as the causative agent of syphilis. The modalities which accompanied the attribution of its aetiological status ('probable', 'in all likelihood' etcetera) were eventually omitted.”

“Although the aetiological concept of syphilis became more firmly entrenched, it also had to meet a challenge from an unsuspected quarter. By a strange coincidence the year 1905 not only witnessed the discovery of Spirochaeta pallida but also the discovery of another spirochaete, which was admittedly indistinguishable from the first one yet presumably different, because it was found in a disease that was (presumably) different from syphilis. This microbe was called Spirochaeta pertenuis by its discoverer, Aldo Castellani, director of the clinic for tropical diseases at Colombo (Ceylon). Castellani had found the spirochaete among sufferers from yaws (framboesia tropica) at his clinic. After consulting Schaudinn about his find - they jointly examined the microscopic preparations - Castellani drew the following conclusion as to the nature of his spirochaete:

"In my view this species is at the moment morphologically indistinguishable from Spirochaeta pallida (Schaudinn). But because I believe that yaws differs from syphilis, I am inclined to think that the spirochaete I have found in yaws - if it figures indeed in the aetiology - must be biologically different from the syphilis spirochaete. I therefore suggested the name Spirochaeta pertenuis seu Pallida".

These considerations clearly support the observation made by Fleck in a related context, that it is the disease that defines the causative agent rather than the other way around (18/27). The same view was expressed several decades later. Writing about the classification of pathogenic treponemes, Paul Hardy Jr. stated in 1976 that"[..] the identity of some members of this group depends more upon certain features of the diseases they produce than upon specific characteristics of the organisms themselves". If Castellani had concluded that Spirochaeta pallida apparently causes syphilis on some and yaws on other occasions, he would have violated the principle of aetiological specificity. If the diseases are different, then the causes must be different (although as yet no difference was discernable!). But are syphilis and yaws really distinct disease entities?”

What this tells us is that the association of the T. pallidum with the syphilis disease was tenuous at best. This was even known by Schaudinn himself. On page 56 of the book A System of Syphilis, the author, Russian zoologist Elie Metchnikof, stated that in a personal communication from Schaudinn, he had admitted that he had difficulty in finding the spirochetes and that, at times, he could only find a single example after a whole day’s search. Schaudinn also admitted in the letter that he felt that the spirochetes he found were different from others within the genital tract, but that he had no definitive proof of his belief:

“Some days before this was published I received a letter from Schaudinn, dated May 2, in which he told me of his discovery, and asked me to send him films taken both from the primary lesions and from the enlarged glands of syphilitic monkeys. He told me the difficulty he had sometimes experienced in finding these spirilla, as he had actually at times only found a single example after a whole day’s search. At the end of this letter Schaudinn expressed his opinion in the following words as to the two different varieties of spirochaetes “I have at the present time no doubt at all that the S pirochaete pallida is distinct from the other varieties which are to be found in the genital tract, although up to the present I can adduce no definite proof of my opinion.”

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/430116

It is clear from this admission by Schaudinn that T. pallidum was not found in abundance of all cases of the disease that it was supposed to cause. However, the inability to always find the spirochetes in large numbers is only part of the problem in regards to fulfilling the first of Koch's Postulates. Today, it is estimated that 50% of those with syphilis are asymptomatic:

“Approximately 50% of people with syphilis are asymptomatic. The progression of syphilis is divided into three stages; primary, secondary and tertiary. An asymptomatic latent period, which may last more than a decade, separates the secondary and tertiary stages.”

https://bpac.org.nz/BT/2012/June/06_syphilis.aspx

In other words, in half of the cases where the T. pallidum bacterium is detected, it is found in those who are healthy and symptom-free. Even in those with symptoms, it is not always found in abundance. Thus, Schaudinn and Hoffman's bacterium fails the two core tenets of Koch's very first Postulate. We could honestly end our dissection of syphilis as a bacterial disease right here. However, for the fun of it, let's move on to Postulate # 2.

2. The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture.

In order for a microbe to be considered a valid independent variable in order to be used in experiments to determine cause-and-effect, the microbe must be shown to exist in a purified (i.e. free of contaminants, pollutants, foreign materials, etc.) and isolated (i.e. separated from everything else) state. In microbiology terms, a pure culture means that the culture contains nothing but the single organism of interest. Koch knew that obtaining a pure culture was a vital and logical requirement as it negates any potential confounding variables (i.e. other microorganisms) which could influence the results. However, as we learned with Siegel's Cytorrhyctes luis, there were competing microorganisms claimed to be found in syphilitic cases. According to a paper published in 1912 by Hideo Noguchi, M.D, there were numerous microbes over the previous few decades which were, at one point or another, considered the causative agent of syphilis, including a bacterium discovered by Lustgarten which was indistinguishable from the tuberculosis bacteria found by Koch. However, this bacterium was also found in other diseases, healthy people and in normal smegma (combination of shed skin cells, skin oils, and moisture in the male/female genitalia) and was ultimately decided not to be the cause of syphilis:

Experimental Research in Syphilis

“Research in syphilis became henceforth increasingly active, and the discoveries of the causative organism were announced year after year from different quarters, only to be disproved after a shorter or longer period of refutation and controversy among the investigators at the time. Hallier, in 1869, found in the syphilitic blood his Coniothecium Syphilicum and held it as the cause. Lostorfers, in 1872, announced his discovery of minute sparkling granules in the Syphilitic blood which was kept for a few days in a moist chamber, but his finding was discredited by Neumann. Biesiadecki, Vajda and others. Then came, in 1878-9). Klebs' discovery in chancre-juice of numerous actively mobile granules and rods which he called Helicomonades. In 1888, Birch-Hirschfeld stained in the tissues from gumma, papules, and chancres, minute bacteria which others considered as mast-cell granules, while Martillean and Hamonic reported in the same year their alleged success in reproducing the syphilitic lesions in pigs and monkeys with their bouillon cultures of cocci and bacteria. In 1884, the well-known discovery of Lustgarten was heralded from Weigerfs laboratory. He demonstrated the presence of a bacillus in certain syphilitic products which resembled the tubercle bacillus discovered by Koch in 1882. The finding was confirmed by a number of reputable bacteriologists, among whom were Doutrelepont, Schütze, Giletti, de Giacomi, Gottstèin, Babes and Baumgarten. It soon met with severe criticism, however, by Alvarez, Tavel, Klcinpcrcr, Mailerstock, Bitter and many others, who not only failed to find this bacillus in the sections of the syphilitic tissues, but found it in other diseases as well as in normal smegma. Tlius the discovery of Lustgarten gradually passed from general interest. In spite of Lustgartens mistake, a great many investigators went further on to find the real organism of syphilis. Most of them described the cocci-like granules in the blood or lesions of syphilitics and claimed to have obtained pure cultures of so-called syphilis bacillus or syphilis coccus from the blood or glands. Van Niessen siill asserts that a poly-morphous bacillus which he obtained from the syphilitic blood and named syphilomyccs is the cause of syphilis. He maintains that Spirocheta pallida is only one of the life cycles of this bacillus, although Hoffmann points out that there is absolutely no resemblance between the pallida and Van Niessen's bacillus in any stage of development. Similar bacilli were reported to lie present in the syphilitic blood, by de Lisle and Jullien, Paulsen, Joseph and Piorkowski, but they are now considered to be due to external contamination. There are also certain investigators who claim to have found protozoa in syphilitic products, hut their findings were soon disproved as mostly due to the artefact or decomposition products.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)17741-5

As there are many competing microorganisms within the fluids of syphilitic patients, it becomes absolutely essential to make sure that whatever microbe is being studied as a potential causative agent is separated from any of these other microorganisms. However, as we learned earlier, T. pallidum cannot be grown in a pure culture. This was confirmed in a 1981 review of the attempts to grow the bacterium in a pure culture. It was stated that, despite many attempts with various methods over 75 years, cultivation of T. pallidum remained unsuccessful. When success was claimed, independent reproducibility could not be achieved, and any potential “success” was met with bacterium that were not considered “infectious.” Rather than claiming that T. pallidum was not pathogenic, it was decided that there are other versions of the treponemes that are non-pathogenic:

In vitro cultivation of Treponema pallidum: a review

“In 1905, Schaudinn & Hoffman (82) discovered that T. pallidum caused syphilis. An intense interest then evolved in growing this organism in vitro (99). An analysis of numbers of publications demonstrates the rise and fall of interest: between 1905 and 1920, 78 reports; between 1920 and 1940, 29 reports; and between 1940 and 1966, 20 reports. There are two probable reasons for the decline in interest. First, in the late 1940s penicillin was shown to be very effective in the treatment of syphilis and it was thought that the disease would soon disappear. In the past 30 years, however, the continued epidemic of syphilis demonstrates the fallacy of this thinking. Secondly, the frustration of attempting to grow T. pallidum is indicated by the accumulated failures over the past 75 years. Many intensive, well planned investigations have been performed and many different extracts, culture media, nutrients, and additives have been tested under a variety of experimental conditions, but still T. pallidum has not been successfully cultured in vitro.

Many reports have claimed cultivation of T. pallidum. In 1906, Volpino & Fontana (96), and in 1909 Schereschewsky (83), initially reported in vitro growth. Since then, other claims have been made. In each case, two problems occurred. Other laboratories were unable to reproduce the original findings, or the cultured organisms lost their ability to induce lesions. Subsequent research has shown that some past ''successes" were the result of contamination with non-pathogenic treponemes.”

Because of the issues with obtaining pure cultures with many bacteria, it was eventually decided that there are bacteria that can be considered the cause of disease despite not fulfilling Koch's 2nd accepted criterion for proving pathogenicity. Note that the bacterium for leprosy is also listed among those that cannot fulfill these Postulates:

“It is already widely accepted that some species of bacteria cause disease despite the fact that they do not fulfill Koch’s Postulates since Mycobacterium leprae and Treponema pallidum, (which are implicated in leprosy, and syphilis respectively) cannot be grown in pure culture medium.”

https://mpkb.org/home/pathogenesis/kochs_postulates

Thus, we can see that T. pallidum cannot fulfill either Postulates 1 or 2. Once again, we could easily stop right here in our investigation, but what would be the fun in that? Let's see how well it stacks up with Postulate 3.

3. The cultured microorganism should cause the same disease when introduced into a healthy organism.

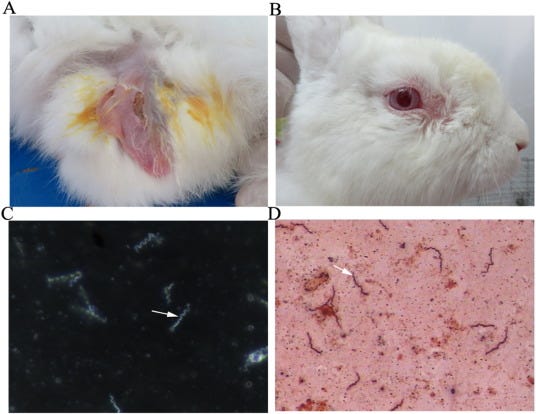

In order for the microbe to be considered the cause of the disease it is associated with; it is necessary to show that the microbe can produce the exact same symptoms of disease when introduced into healthy hosts experimentally. Obviously, if it does not cause the same symptoms, the microorganism would be considered a failure. This creates a rather big problem for T. pallidum because, as syphilis is considered a human disease, there is no animal model that can accurately recreate every stage of the human disease. This means that any information derived from animals is of limited value. As the bacterium cannot be grown in pure culture, there is not enough of it to use, and it cannot be manipulated during experimentation as required by the scientific method. While rabbit models are considered the closest to mimicking the human condition, to date, no animal model can recreate the late stages of syphilis:

The pathogenesis of syphilis: the Great Mimicker, revisited

“Syphilis is a chronic sexually transmitted infection caused by Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum. Its protean clinical presentations earned it the name of the ‘Great Mimicker’. Understanding of disease pathogenesis and how host–pathogen interactions influence the course of disease have been compromised by the facts that the organism cannot be grown in vitro and, as an exclusively human pathogen, inferences made from animal models are of limited applicability. Many questions remain about how T. pallidum biology contributes to distinctive features of syphilis, such as its ability to persist in the presence of a brisk host response or its propensity for neuro-invasion and congenital transmission.”

“The study of T. pallidum and syphilis pathogenesis has been hindered by the fact that it cannot be cultivated for sustained periods using artificial media. While it can be passaged for a limited number of generations with a generation time of 30–33 h using rabbit epithelial cell monolayers under micro-aerobic conditions at 33–35 ◦C, these methods currently provide neither the quantity of organisms nor the flexibility in their manipulation to make them useful tools for the study of T. pallidum –host interactions. In vivo propagation by inoculation of rabbit testis yields substantial numbers of organisms and is the most commonly used method for generating organisms for study. Similarly, while several animal models for syphilis have been described, rabbit models most closely resemble the primary infection and pathogenesis of disseminated infection. Late-stage manifestations have not been documented in any animal model [9].”

In this next source, it is stated that even though the rabbit model can produce a similar (i.e. resembling without being identical) disease, the understanding of T. pallidum pathogenicity is hampered by difficulties with genetically manipulating rabbits and the lack of appropriate immune reagents. While mice are said to be able to be “infected” with the bacterium, the characteristic lesions cannot be recreated and thus, the limited and incomplete rabbit model remains the best attempt to experimentally recreate the human disease:

Characterization of Treponema pallidum Dissemination in C57BL/6 Mice

“Rabbits are the most commonly used animal model in studies of syphilis because the pathological changes and serological responses of rabbits after infection with T. pallidum are similar to those in humans. However, although the bacterium was identified microscopically early in the 20th century, our understanding of the pathogenicity of T. pallidum is still limited owing to difficulties in genetic manipulation of rabbits. Additionally, appropriate immune reagents have not been established, making such models even more difficult to establish (3–6).

In contrast, mice, which have a well-defined genetic and immunological background, are frequently used for studies of many infectious diseases. Indeed, many studies of T. pallidum infection in inbred mice have been reported. T. pallidum has been shown to be able to infect mice and persist within mice. However, infection in mice was not accompanied by skin lesions, as observed in other animal models (7–9), and no further studies have evaluated the merits and demerits of mice as subjects of T. pallidum.”

“Different animal models have been tested, including mice; however, it seems that no model has been shown to be better than rabbits. Moreover, except for two studies (7, 16), no reports have demonstrated the development of cutaneous lesions after T. pallidum inoculation in mice.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7819853/

Returning to the book Spirochaetes, Serology, and Salvarsan: Ludwik Fleck and the construction of medical knowledge about syphilis, it is stated that the artificial rabbit syphilis is not the same as human syphilis. Only a few of the characteristics of the human illness can be artificially recreated in rabbits. It is stated that there is a problem with translating the results from the artificially recreated rabbit disease and considering it equivalent to the human disease. These animal studies are thus considered not representative or reliable in regard to saying anything about human disease. They are likened to weak analogies:

“In this particular case the 'object', human syphilis, was 'brought home' by having it transmitted to rabbits. It is evident, however, that by this 'translation' the very object changes its character. Rabbit syphilis is not the same as human syphilis. Only a few of the manifestations characteristic of the human affection are also found in the artificially induced disease of the rabbits (the main reason for considering the latter condition a form of syphilis at all is that it can in turn be transmitted to apes and monkeys, which then show many more symptoms similar to those of human syphilitics). Translation, as Latour would say, involves treating situations that are not equivalent as if they were equivalent. A substance that is effective for rabbit syphilis would not automatically also be effective for human syphilis. Traditionally, the problem has been formulated as turning on the representativeness and reliability of the 'animal model' for extrapolating the results obtained in animal studies to the human counterpart. A recent publication concludes that such studies are little more than heuristics, based on weak analogies. The lamentation uttered in 1929 by the Dutch gynaecologist J.A. van Dongen with regard to the results of female sex hormone therapy must sound familiar to many laboratory and clinical researchers: "the route from the white mouse in the laboratory to homo sapiens in the consulting-room is a long route that is not yet bridged".

As a final nail in the coffin of Postulate 3, we return to the 1912 paper by Hideo Noguchi, M.D. Here, we find that Schaudinn was unable to fulfill Koch's Postulates as he could not obtain a pure culture and recreate the same disease in animals experimentally:

“Thus Spirochada pallida, Schaudinn, fulfilled almost all the requirements laid down by Koch before being accepted us the causative agagen of syphilis. The only missing link was that it pure culture of this organism should he able to produce the pathologic changes in experimental animals similar to those found in human syphilis.”

It should hopefully be clear that Schaudinn and Hoffman's T. pallidum was unsuccessful in fulfilling any of the first 3 of Koch's Postulates for proving a microorganism as the causative agent of disease.

T. pallidum is not always found in abundance in those with disease and is regularly detected in those who are healthy.

T. pallidum cannot be grown in a pure culture and cannot be isolated from the many known microorganisms within the fluids of syphilitic patients that were, at one point or another, also claimed to be the causative agent.

There is no animal model that can successfully recreate the human disease.

T. pallidum, by default, fails the 4th Postulate as the bacterium can not be reisolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent. Thus, what we have is the very definition of a case of correlation equaling causation that blatantly ignores the required standards that were agreed upon as neccessary to be satisfied in order to obtain definitive proof.

How many lives have been ruined over the fraudulent claim that the symptoms of detoxification lumped together as syphilis are caused by a bacterium that was never scientifically proven to cause any disease whatsoever? How many people had their health destroyed by toxic penicillin injections which napalmed their entire body to stamp out a bacteria that is found in those who are healthy as well? Just because a bacterium is found in people with symptoms of disease does not mean it is the cause of said disease. Standards were established that were supposed to be followed in order to avoid the trap of correlation equaling causation. Sadly, this criteria has regularly been trampled on and ignored in order to to claim a causative agent despite the failure to prove one. Sadly, the stigma of the diagnosis and the damage from the treatment has negatively impacted those unfortunate enough to receive the label and, as in the case of my relative, they paid the ultimate price as the belief in a bacterial cause cost them their lives.

served up another excellent helping of Freedom of Information requests including the "SARS-COV-2" genome, RSV, measles, and the spike protein. just released the second part of her fantastic look at the absurdity of the numerous diseases cropping up in the headlines currently.Three of my favorite people, Jerneja Tomsic PhD, Jordan Grant MD, and Dawn Lester discuss the problems with ‘science’ to find the answer to the question: Where did it all go wrong?"

https://odysee.com/@David_Parker_and_Dawn_Lester:5/Science-Scientism---Pseudoscience:d

Jerneja Tomsic also joined

to discuss the unscientific nature of both the PCR “tests” and the viral genomic sequencing process, as well as the dogmatic, consensus-based nature of the health sciences community.https://www.bitchute.com/video/fXMwlsUj4ITX/

and Dr. Mark Bailey both joined Patrick Timpone for an engaging cconversation covering many aspects of the "viral” lie.

Great post- lots of research in this one. Syphilis supposedly leads to insanity- but that's more likely due to treatment with mercury. Is "treatment" the real illness?