At this point in time, we really should be getting used to this rotating cast of colorful “viral” characters being paraded about as the causes for the exact same symptoms of disease. If it isn't “SARS-COV-2,” it's one of the influenza “viruses” running amuck. If it isn't influenza, it must be the “adenovirus.” No wait, it is most likely “norovirus.” Nah, it has to be the “respiratory syncytial virus.” Or perhaps it is the “human metapneumovirus.” Marburg or Ebola? Dengue? Avian flu? Strawberry hepatitis A? Tomato flu? How many invisible “viral” boogeymen must be identified as the cause for the exact same symptoms of disease before the public starts to catch on to this recycled script?

Recently, we have seen an influx of fungal and bacterial culprits cropping up to take the place of the overused “viral” plot device. Perhaps the CDC is aware that it is pushing the boundary of believability with these numerous warnings of constant “viral” threats? There have been alerts of bacterial outbreaks such as salmonella and listeria in certain food items. We've seen streptococcus A play a starring role in cases of sore throats in children. The CDC warned that the “deadly” Burkholderia pseudomallei was found in the gulf states as well as in Missouri. We've even had Candida auris emerging as an urgent antimicrobial resistance threat in hospitals as well as cases of fungal meningitis in Mexico.

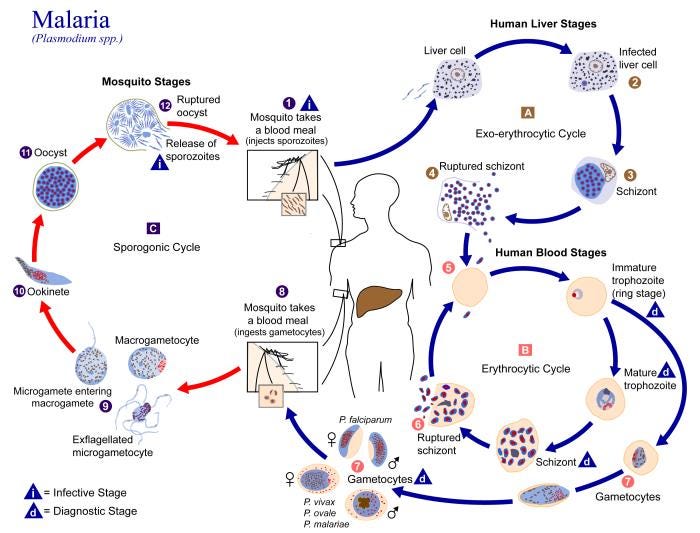

Despite the overloading of a plethora of pathogens that we must contend with, the CDC has now added one more culprit to the list. This is an invisible boogeyman that most here in North America probably would not have thought to have seen in the headlines locally any time soon. The current pathogen that we are supposed to be terrified of and on the lookout for is the protozoa known as the plasmodium parasite. This single-celled organism is the associated cause of malaria, a disease that is mostly seen in the southern hemisphere, especially in the African nations. It has now somehow found its way to American shores.

According to the CDC, while we see around 2000 cases of malaria every year here in the US, these cases are relegated to those who traveled overseas to endemic countries. As malaria is not considered contagious, it is not a major concern if these cases are coming from those who traveled abroad. However, the CDC wants us to know that recently, cases were identified where the individuals had no history of travel to an endemic area. Thus, these are rare local cases where the victim acquired the disease from an “infected” mosquito right here in the US.

So far, there are a total of 5 such cases; four in Florida and one in Texas. It is said that these cases are not related in any way. However, surveillance is ongoing in order to identify any more cases in the surrounding areas where they occurred. While the CDC pushed the red panic button to sound the malaria alarm, all patients have recovered and the risk of catching the disease is considered extremely low. Despite the fact that these cases are considered extremely rare here in the US, the CDC has alerted clinicians to consider a malaria diagnosis in any person with a fever of unknown origin regardless of their travel history.

Locally Acquired Malaria Cases Identified in the United States

“CDC is collaborating with two U.S. state health departments with ongoing investigations of locally acquired mosquito-transmitted Plasmodium vivax malaria cases. There is no evidence to suggest the cases in the two states (Florida and Texas) are related. In Florida, four cases within close geographic proximity have been identified, and active surveillance for additional cases is ongoing. Mosquito surveillance and control measures have been implemented in the affected area. In Texas, one case has been identified, and surveillance for additional cases, as well as mosquito surveillance and control, are ongoing. All patients have received treatment and are improving. Locally acquired mosquito-borne malaria has not occurred in the United States since 2003 when eight cases of locally acquired P. vivax malaria were identified in Palm Beach County, FL (1). Despite these cases, the risk of locally acquired malaria remains extremely low in the United States. However, Anopheles mosquito vectors, found throughout many regions of the country, are capable of transmitting malaria if they feed on a malaria-infected person (2). The risk is higher in areas where local climatic conditions allow the Anopheles mosquito to survive during most of or the entire year and where travelers from malaria-endemic areas are found. In addition to routinely considering malaria as a cause of febrile illness among patients with a history of international travel to areas where malaria is transmitted, clinicians should consider a malaria diagnosis in any person with a fever of unknown origin regardless of their travel history. Clinicians practicing in areas of the United States where locally acquired malaria cases have occurred should follow guidance from their state and local health departments. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of people with malaria can prevent progression to severe disease or death and limit ongoing transmission to local Anopheles mosquitos. Individuals can take steps to prevent mosquito bites and control mosquitos at home to prevent malaria and other mosquito-borne illnesses.”

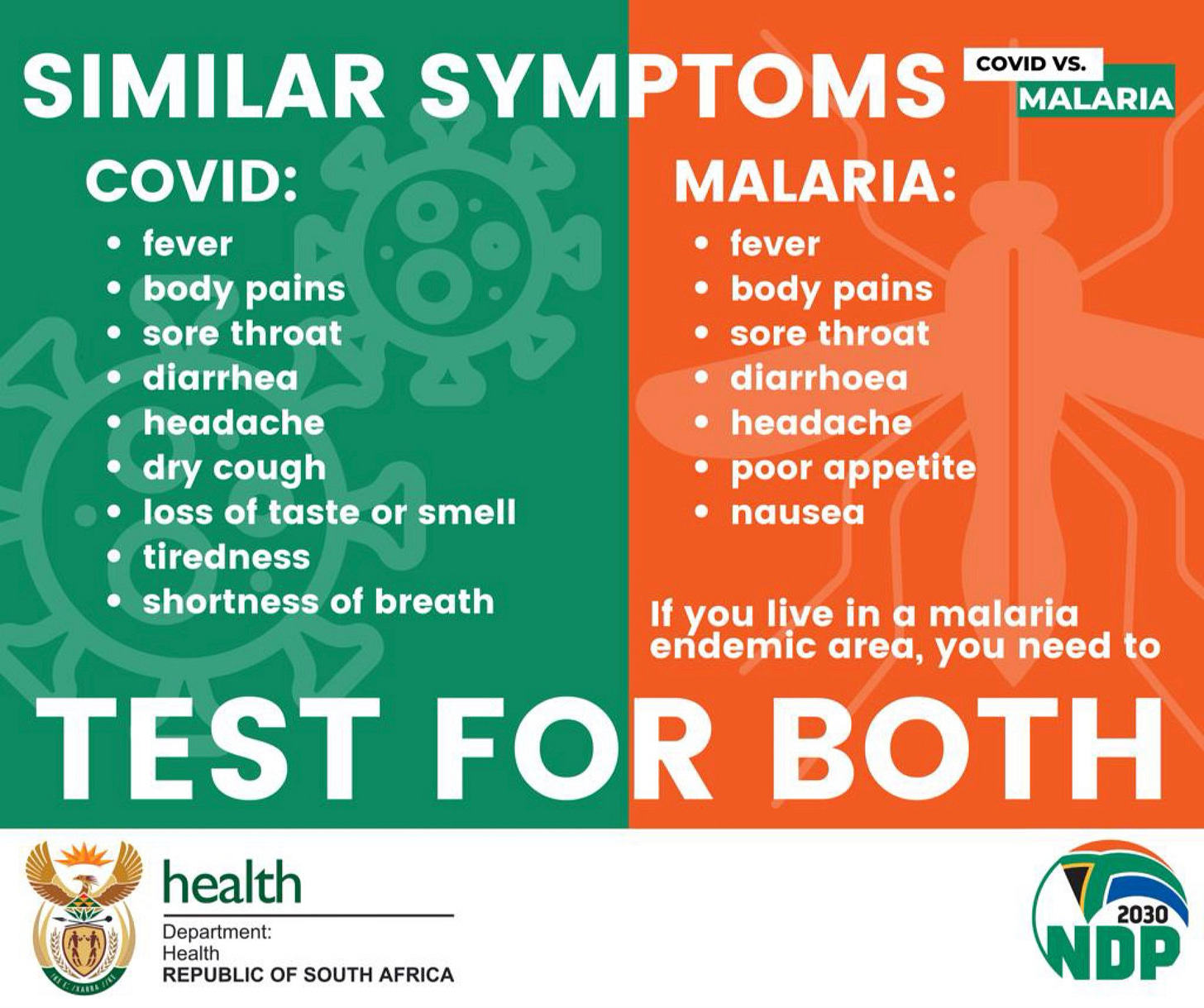

As for the symptoms that clinicians should be on the lookout for, the CDC states that the clinical manifestations of malaria are non-specific and include fever, chills, headache, myalgias, and fatigue, as well as the possibility of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. To those paying attention, these are the exact same symptoms associated with many other diseases already seen in the US. The CDC notes that cases may spring up within 7 days after a mosquito bite or as late as a year. In other words, people better get their calendars out and mark down the date of any mosquito bites they receive in order to ensure that the non-specific symptoms that they may suffer at any time within a year from that date are not malaria. If these symptoms are not treated promptly, the CDC warns that one may experience chronic infection causing relapsing episodes. Relapses may occur after months or even years without symptoms:

“Clinical manifestations of malaria are non-specific and include fever, chills, headache, myalgias, and fatigue. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea may also occur. For most people, symptoms begin 10 days to 4 weeks after infection, although a person may feel ill as early as 7 days or as late as 1 year after infection. If not treated promptly, malaria may progress to severe disease, a life-threatening stage, in which mental status changes, seizures, renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and coma may occur.”

“P. vivax and P. ovale canremaindormant in the liver and such infections require additional treatment; failure to treat the dormant hepatic stages may result in chronic infection, causing relapsing episodes. Relapses may occur after months or even years without symptoms.”

“Consider the diagnosis of malaria in any person with a fever of unknown origin, regardless of international travel history, particularly if they have been to the areas with recent locally acquired malaria.”

https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2023/han00494.asp

If malaria symptoms are non-specific, just how accurate are the diagnoses based upon these non-specific symptoms? According to mainstream media sources, Christopher Shingler, the Texas man who was diagnosed with malaria, was initially misdiagnosed with either “Covid-19” or the catch-all “viral” infection depending on the source one reads. Interestingly, according to Shingler, he stated that his whole National Guard unit was getting torn up by mosquitoes for days, yet he was the only one who experienced any symptoms afterwards:

U.S. malaria patient says the disease was initially misdiagnosed

“Medics gave the 21-year-old tests for Covid-19, and at a hospital the Brazoria County resident was told he likely had a viral infection.”

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/rcna92142

Texas man who got malaria says he was misdiagnosed with Covid-19; disease is rare in U.S.

“Christopher Shingler, a 21-year-old National Guard member stationed near the Texas-Mexico border, caught one of the first cases of malaria contracted in the U.S. in 20 years — but his case was initially (mis)diagnosed.

With symptoms of fever, difficulty eating, and vomiting, Shingler was initially tested for Covid-19 by medics — but it took further tests for his malaria to be confirmed, reported NBC News.”

“We were getting torn up by mosquitoes, chiggers, whatever you can think of, you can name,” Shingler stated. “We were getting torn up the entire time we were out there, especially that first night.”

But, he added, he was not aware of anyone else from his unit who got sick from the insect bites.”

We are told that this man was initially diagnosed with either “Covid-19” or some other related “viral” illness based upon his symptoms and testing. However, for some reason, perhaps due to no one else in his unit displaying any signs or symptoms of disease whatsoever, further testing was carried out and his diagnosis changed. While it is not stated what testing was done to “confirm” his diagnosis of malaria, one study found that the rapid diagnostic tests, commonly used here in the US, have a false-positive rate of 26.8% whereas the false-negative rate was 48.6%. The positive predictive value was 58.1% whereas the negative predictive value was 67.6%. It was concluded that the tests should not be used as a stand-alone test kit. Another study looked at the blood smear test, considered the “gold standard” for malaria diagnosis, and found that the positive predictive value was low with 27/73 (37%) patients diagnosed with malaria that did not have the disease. When US Peace Corps volunteers were diagnosed by blood smear in local clinics in sub-Saharan Africa, the diagnosis could be confirmed in only 25% of cases. It would seem that Shingler's symptoms went from being a typical “viral” cause into a rare case that was claimed to be caused by parasites via way of mosquito bites based upon inaccurate tests.

This leaves us with some very interesting questions. How did this diagnostic mistake happen? Is it that easy to mistake a “viral” case of disease over one claimed to be caused by parasites? Is it even true that the symptoms of disease known as malaria are rare here in the US? Was the link between the symptoms claimed as malaria and the plasmodium parasite ever proven by fulfilling Koch’s Postulates? Is there any scientific evidence backing up the assertions made by the CDC and other health organizations about the cause of this disease? Or is this just another in a long line of clever smoke and mirror tricks used to fool the masses into believing in yet another fictional threat for the same symptoms of disease requiring a specific pharmaceutical regimen as a “cure?” Let's find out.

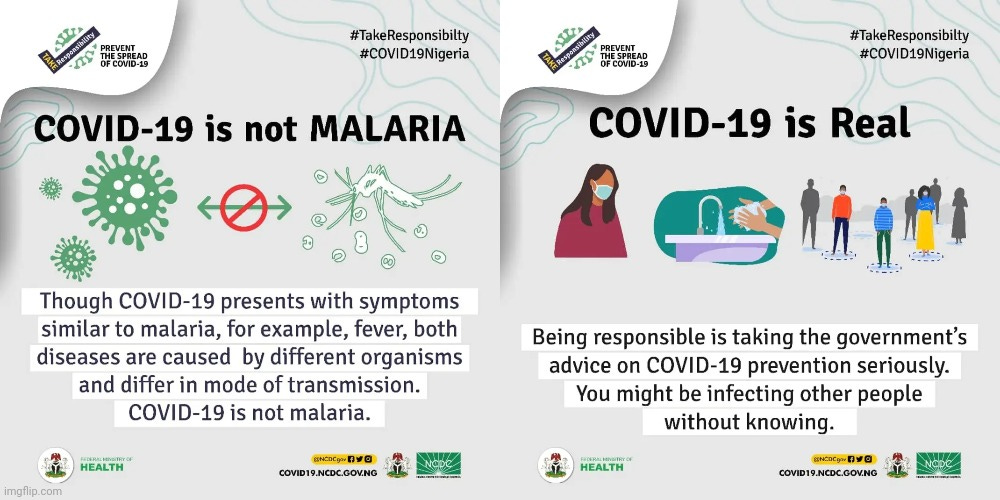

A quick investigation into Christopher Shingler's case of mistaken identity between “Covid-19” and malaria finds that both diseases are, for all intents and purposes, identical. In fact, these “diseases” are said to mimic each other in many ways. Even the lung x-rays look the same between the two. The Nigerian CDC had to put out an ad campaign trying to convince the population that these are different diseases, but they could only point to the fictional organisms said to be the causative agents and the scientifically unproven mode of transmission as the ways to differentiate them.

Interestingly, Africa had the least amount of “Covid” cases in the world, primarily due to the fact that the majority of the people presenting with these symptoms were diagnosed as malaria patients rather than as “Covid.” In cases where “Covid” is considered the correct diagnosis, anti-malarial drugs such as chloroquine and hydroxychloriquine are given as there is no standardized treatment protocol for “Covid.” Blurring the lines even further, there are said to be common clinical, pathological, and immunedeterminant levels shared between these two “separate” diseases. This leads to difficulty in diagnosing between them, and it is said that they may be commonly misdiagnosed for one another, as seen in the case with Shingler in Texas:

The striking mimics between COVID-19 and malaria: A review

“According to the recent WHO data on COVID-19 morbidity rates, the African region reported the least number of COVID-19 confirmed cases as of 25th July, 2022 is (9,187,634) followed by the Eastern Mediterranean region (22,490,905), and highest numbers reported for the European region (238,567,709) (2). Thus far, there is no standardized protocol for the management of COVID-19 infection, nevertheless, several regimens including antimalarial, antiviral and immune system strengthening medications have been prescribed (6). Malaria and COVID-19 can have similar clinical presentations such as but are not limited to fever, backache, fatigue, shortness of breath, diarrhea, headache, stomach cramp, muscle pain, etc. (7). Additionally, several other common presentations at the clinical, pathological, and immunedeterminants levels have been illustrated. These common symptoms make the diagnosis challenging in places where proper health access and facilities are scarce, and diagnosis does not involve high throughput PCR testing used worldwide (8). Again, due to scarce facilities and large number of cases in most hospitals in Sub-Saharan Africa, empirical treatments are often given without laboratory testing (diagnosis). Thus, malaria cases might be misdiagnosed as COVID-19 or vice versa in both malaria-endemic and malaria-free zones (9), though the concomitant infection was also reported (10).”

“Covid” is not the only “disease” said to present with the same and/or similar symptoms as malaria. There are many conditions that present with the exact same symptoms that must be ruled out in order to confirm a malaria diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of malaria includes bacterial “infections” as well as numerous “viral infections” such as dengue, yellow fever, zika, ebola, and any of the numerous respiratory “viruses.”

There are no specific symptoms that differentiate malaria from other so-called diseases. These same symptoms regularly occur in the US under different names. The only difference that can be claimed is the assumed cause, whether it is “viral,” bacterial, fungal, or, as in this case, parasitic. Thus, we must ask whether it was ever scientifically validated that the non-specific symptoms associated with malaria is actually caused by the plasmodium parasite. Was this parasitic discovery, and the presumed relationship to malaria, proven by fulfilling Koch's Postulates, considered the necessary requirements to establish that a specific microorganism causes a specific disease? To answer these questions, we must first look to the work of two men who laid the foundation for the claim that the plasmodium parasite causes malaria, and that this parasite can be transmitted via the mosquito.

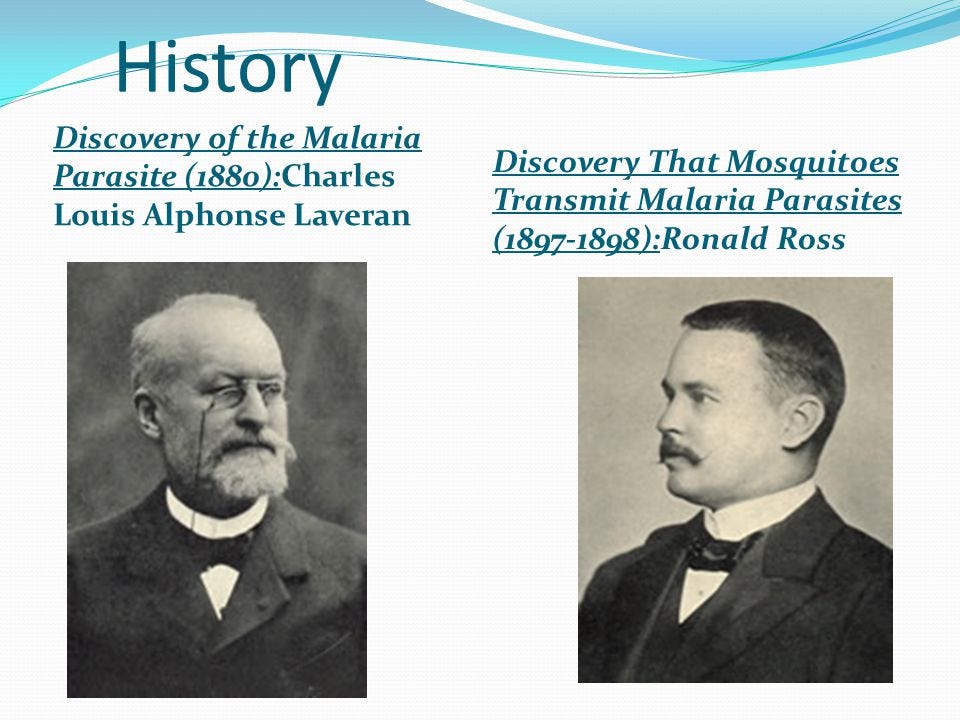

According to the CDC, malaria was originally considered to be caused by the bad air that was coming from the surrounding marshlands. The disease derived the name malaria from the Italian word “mala aria,” which translates to “bad air.” However, with the rise of Louis Pasteur's germ theory, this idea was disregarded and a bacterial cause was searched for instead. Italian and American researchers investigated the marshlands, and various algae, aquatic protozoa, and bacteria, such as Bacillus malariae in Italy, were incriminated as causal agents in the disease. Yet, for reasons undefined, these presumed causal agents were disregarded, and it wasn't until French physician Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran discovered the plasmodium parasite in 1880 that a single organism was accepted as the true cause.

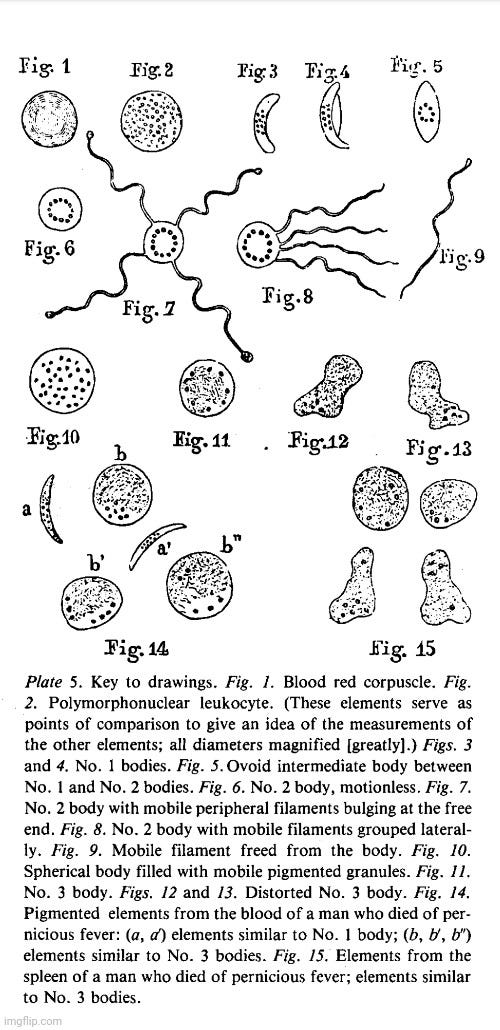

To discover his parasite, Laveran examined the blood of malaria patients and saw filiform elements that he originally thought were leukocytes, i.e. normal blood cells. However, as the elements he observed were more mobile and had various forms, the French physician decided that these were not normal constituents of the blood, but rather parasites. According to the editors notes at the beginning of the 1982 reprinting of Laveran's 1880 paper, it is said that this was the third time microorganisms were found in the blood and considered to be the causative agent of disease. The first two were associated with relapsing fever and anthrax. Interestingly, many other investigators noted different microorganisms in the blood of malaria patients -Meckel (1847), Furichs (1858), Planer (1854), Delafield (1872), and Jones (1876)- yet as none of them developed their observations in a systematic manner, it seems Laveran's parasite won by default:

“During a series of microscopic blood examinations of malaria patients in Constantine, he discovered spherical pigmented bodies with ameboid movement which he had until then confused with pigmented leukocytes. This was the third time that micro-organisms had been found in human blood, the first two being the causative agents of relapsing fever and anthrax. When Laveran's discovery was confirmed, the Academy of Sciences in Paris elected him to honorary membership. In 1904, Laveran retired from military service and joined the Pasteur Institute, where he devoted himself entirely to bacteriologic and parasitologic research. He published more than 600 scientific papers dealing with malaria and many other tropical diseases. In 1907, he received the Nobel Prize as "initiator and pioneer of the pathology of protozoa."

Many others had seen various objects in the peripheral blood of malaria patients-Meckel (1847), Furichs (1858), Planer (1854), Delafield (1872), and Jones (1876)-yet none developed their observations in a systematic manner. Laveran's first communication appeared in the Bulletin de l'Academie de Medecine, 19:1235-1236, 1880. The brevity of the original article did not do justice to this monumental discovery.”

Looking at Laveran's 1880 paper, it is clear that, at no point, was any parasite proven to cause the disease he associated it with. The paper is riddled with assumptions and the mistaken belief that correlation equals causation. Upon examining the blood of a malaria patient, Laveran noticed among the red corpuscles elements that seemed to him to be parasites. He then examined the blood of 44 malaria patients and found these same elements in 26 cases (i.e. not all of them). While Laveran stated that these elements were not found in those who were not ill, we will see that this statement was proven untrue by later research. In any case, this observation somehow convinced Laveran of their parasitic nature. He referred to these elements in three forms: No. 1, 2, and 3.

Laveran noted that the rapid and varied movements of the filaments of No. 2 bodies, as well as the modifications of form they go through, led him to believe they were like an organism known as an infusoria, which are minute freshwater life forms that include amoeba, ciliates, euglenoids, protozoa, unicellular algae and small invertebrates. He wondered if the bodies he referred to as No. 1 and No. 2 could be the result of an agglutination of cystlike parasites formed by normal elements in the blood. He also pondered whether they could be fully developed parasites that sometimes leave the bodies to lead independent lives. The latter was the hypothesis that he settled upon. Laveran noted that, once free, these bodies acted like filariae, i.e. worm-like parasites seen in insects, and claimed that several researchers thought that filariae play an important part in the pathology of swamp fever.

Laveran posited three reasons why his elements were parasites similar to those associated with swamp fever.

They are always found in malaria cases (although he admitted that they are not present in every case of the disease).

The elements vanish from the blood after long treatments of quinine sulfate, and thus the patients are considered “cured.”

Similar elements desctibed as No. 1 and 3 are found in the blood of patients who have died of pernicious fever (i.e. these elements are not specific to malaria).

Laveran concluded that the presence of these elements that he assumed were parasites in the blood were probably the principal cause of malaria and asked several questions that were not answered by his paper:

Where did these “parasitic” elements found in the blood of malaria patients come from?

How do they get into the human system?

How do they cause intermittent fever and other signs of malaria?

A Newly Discovered Parasite in the Blood of Patients Suffering from Malaria. Parasitic Etiology of Attacks of Malaria.

“On 20 October of this year, while I was examining microscopically the blood of a patient suffering from malaria, I noticed, among the red corpuscles, elements that seemed to me to be parasites. Since then, I have examined the blood of 44 malaria patients; in 26 cases, these same elements were present. This convinced me of their parasitic nature. These elements were not found in the blood of patients who were not ill with malaria. I will describe these elements as No.1, No. 2, and No.3. Eventually, it will become evident that this nomenclature is useful as it makes no assumptions as to the nature of the parasites.”

“The very fact that the parasitic organisms above described are found in an alkaline medium such as blood leads one to think that the parasites are of animal and not vegetable origin. The rapid and very varied movements of the filaments of No.2 bodies, as well as the modifications of form they go through, lead the researcher to think of an organism like an infusoria. Is it as I first thought, an amoeba, or could bodies No. 1 and No.2 be the result of an agglutination of cystlike parasites formed by normal elements in the blood? Could these parasites, fully developed, be the mobile filaments of No.2 bodies, that sometimes leave the bodies to lead independent lives? This last hypothesis seems to me the most probable one. Once free, the mobile filaments are very much like filariae; and several researchers, Hallier among them, think filariae play an important part in the pathology of swamp fevers. The small, mobile, bright bodies, almost always present in the preparations, may be the first phase of an evolution of an organism. Quite often, one of these little bodies attaches itself to a red corpuscle and makes the effort, if I may say so, to penetrate into the interior.

The important role played by the parasites above described in the pathogenesis of swamp fevers may be evaluated as follows:

(1) These parasites are found only in the blood of patients suffering from malaria. It is fair to add that they are not always found there but, since only one or two drops of blood are examined, it is obvious that when the parasites are very scarce, their presence is difficult to establish.

(2) These parasites, while abundant in the blood of patients who have suffered from the fever for some time and who received no regular treatment, vanish from the blood of those treated for a long time with quinine sulfate, and who may be considered cured. Many of the patients I examined had received quinine sulfate for several days, and that could explain the high percentage of negative results I obtained.

(3) In the blood of patients who have died of pernicious fever, one finds a great number of pigmented elements that look very much like No. 3 bodies or, in rarer instances, No.1 bodies. The presence of these elements in capillaries of all tissues and of all organs, particularly of the spleen and liver, is characteristic of acute malarial infection. Fig. 14 shows pigmented bodies found in the blood of a man who died of pernicious fever, and Fig. 15, similar bodies found in spleen tissue in another case of pernicious fever. The resemblance of these bodies to those I described as No.1 bodies and No. 3 bodies, and whose parasitic nature I believe to have established, is striking.

From where come these parasitic elements found in the blood of malaria patients? How do they get into the human system? How do they cause intermittent fever and other signs of malaria? Only now is one able to pose these important questions.

Conclusion

Parasitic elements are found in the blood of patients who are ill with malaria. Up to now, these elements were thought incorrectly to be pigmented leukocytes. The presence of these parasites in the blood probably is the principal cause of malaria.”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6750753/

Laveran's questions about how these parasites found their way into the human body in order to cause disease remained unanswered for 17 years until Sir Ronald Ross, a British medical doctor, found what he thought may be cells containing similar “parasites” in the stomach tissue of mosquitoes:

“On 20 August 1897, in Secunderabad, Ross made his landmark discovery. While dissecting the stomach tissue of an anopheline mosquito fed four days previously on a malarious patient, he found the malaria parasite and went on to prove the role of Anopheles mosquitoes in the transmission of malaria parasites in humans.”

https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/history/ross.html

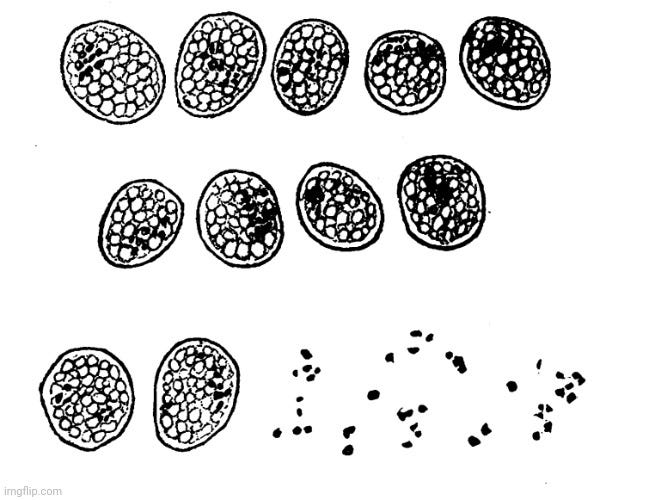

However, did Sir Ross really discover the assumed malaria parasite in the stomachs of mosquitoes, thus proving that these parasites are transmitted to humans via mosquito bites? According to his own words, Ross acknowledged that this endeavor was a difficult one due to there being “no a priori indication of what the derived parasite will be like precisely, nor in what particular species of insect the experiment will be successful.” In other words, Ross went in with the assumption that he could feed the blood of malaria patients to mosquitoes and then find the parasite within them, but he did not know what the parasite would be like or whether mosquitoes could even harbor them. Ross was regularly unsuccessful finding the assumed parasite during numerous attempts with various species of mosquitoes. He admitted to not being able to succeed in tracing any parasite to the ingestion of malarial blood, nor in being able to observe special protozoa in the evacuations due to digestion. That is, until Ross found a new species of brown mosquito that he claimed were difficult to procure due to their rarity. Within this species, he found only 2 mosquitoes that contained “remarkable and suspicious cells containing pigment identical in appearance to that of the parasite of malaria,” which he then went on to describe within the rest of the paper that can be found at the link below:

ON SOME PECULIAR PIGMENTED CELLS FOUND IN TWO MOSQUITOS FED ON MALARIAL BLOOD.

By Surgeon-Major RONALD ROSS, I.M.S., (with note by Surgeon-Major SMYTH, M.D, I.M.S.)

“For the last two years I have been endeavouring to cultivate the parasite of malaria in the mosquito. The method adopted has been to feed mosquitos, bred in bottles from the larva, on patients having crescents in the blood, and then to examine their tissues for parasites similar to the haemamoeba in man. The study is a difficult one, as there is no a priori indication of what the derived parasite will be like precisely, nor in what particular species of insect the experiment will be successful, while the investigation requires a thorough knowledge of the minute anatomy of the mosquito. Hitherto the species employed have been mostly brindled and grey varieties of the insect; but though I have been able to find no fewer than six new parasite of the mosquito, namely a nematode, a fungus, a gregarine, a sarcosporidium (?), a coccidium (?), and certain swarm spores in the stomach, besides one or two doubtfully parasitic forms, I have not yet succeeded in tracing any parasite to the ingestion of malarial blood, nor in observing special protozoa in the evacuations due to such digestion. Lately, however, on abandoning the brindled and grey mosquitos and commencing similar work on a new, brown species, of which I have as yet obtained very few individuals, I succeeded in finding in two of them certain remarkable and suspicious cells containing pigment identical in appearance to that of the parasite of malaria. As these cells appear to me to be very worthy of attention, while the peculiar species of mosquito seems most unfortunately to be so rare in this place that it may be a long time before I can procure any more for farther study, I think it would be advisable to place on record a brief description both of the cells and of the mosquitos.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2408186/

Sir Ross sent his findings to The British Medical Journal, which, in turn, sent them to three other researchers: Dr. Thin, Mr. Bland Sutton, and Dr. Patrick Manson. Both Manson and Sutton responded with their thoughts on Ross's discovery. According to Dr. Patrick Manson, while he felt that Ross did discover cells with a pigment indistinguishable from those characteristic of the malaria parasite, until the cells were stained and their exact structure was more carefully studied, it was impossible to say if they contained parasites. While he was inclined to believe that the cells may contain the malaria parasite, Dr. Manson stated that it was possible that they may contain a parasite that is not the malaria parasite. He also suggested that the pigmented cells may be normal to the species of mosquito that Ross was working with. He felt that the pigment may not represent living parasites at all, but rather a pigment that is taken up by the cells of the mosquitos stomach when ingesting malarial blood. Dr. Manson stated that more work was necessary before this matter could be settled:

"I have examined Surgeon-Major Ross's slides with great interest, and find that his description of the pigmented cells he refers to is accurate. There can be no question that these cells contain a pigment optically indistinguishable from the pigment which is so characteristic a feature in the malaria parasite. The cells are evidently in the wall of the insect's stomach, and are quite different in appearance from any other structure in the preparations. They stand out with remarkable distinctness, the outline of the cell wall, if such it be, being sharply defined, the entire body reminding one of a coccidium-invaded epithelial cell. Until these cells have been stained and their exact structure more carefully studied, it is impossible to say if they contain parasites. Considering the peculiar grouping of the pigment in many instances, a grouping that forcibly recalls what one sees in the living malaria parasite, and the distinctness and regularity of the outlines of the bodies, I am inclined to think that Ross may have found the extracorporeal phase of malaria. If this be the case, then he has made a discovery of the first importance. It is just possible, however, that these cells may be something quite other than this. Possibly, if they do contain a parasite, it may be that this parasite is not the malaria parasite; possibly these pigmented cells are normal to the species of mosquito he is working with; possibly the pigment, though malarial, does not represent a living parasite, for we can conceive that a pigment having been set free in the stomach of the malaria-fed mosquito may be taken up by the cells in the insect's stomach. More work is required before the matter can be finally settled. I have been so impressed by the possibilities of Ross's discovery that I had the accompanying drawings made from his preparations."

Mr. Bland Sutton shared many of Dr. Manson's thoughts. However, he questioned why this pigmented appearance was only found in one species of mosquito. He saw no trace of the malaria parasite within Ross's preparations, although he could not rule it out as they were unstained. Straying from Dr. Manson, Mr. Sutton felt that these appearances did not represent parasites, and that the extra-corporeal stage of the parasite of malaria had not yet been observed. He felt that these preparations did not show any development of the parasite of malaria in the mosquito's stomach:

“What is to me extraordinary about the matter, and requires further explanation, is why this appearance is found only in one species of mosquito. I see no trace of the parasite of malaria itself in these preparations, but, as they are unstained, it does not necessarily follow that it is not there. It will be evident, from what I have remarked, that I consider that these appearances do not represent parasites, and that the extra-corporeal stage of the parasite of malaria, which Koch and Pfeiffer were, I believe, the first to suggest might be found in the mosquito, has not yet been observed, for, so far, all the changes in the form of the crescent, and in the throwing out of flagella, which take place in the mosquito's stomach, can be produced at will (as has been shown by my friend Dr. Marshall, and afterwards verified by Dr. Manson), by the simple addition of distilled water. Although I have not been able to satisfy myself that these preparations show any development of the parasite of malaria in the mosquito's stomach, I hope it will not be considered that I undervalue the great importance of Surgeon-Major Ross's investigations.”

Based upon Sir Ross's own words as well as those of Dr. Manson and Mr. Sutton, it is rather clear that Sir Ross, in no way, proved that he had found the malaria parasite in the stomachs of mosquitoes. Even if he had, this would not mean that a mosquito would be able to transmit a parasite to a human in order to cause disease. While not entirely necessary, we can throw even more shade on Sir Ross's findings by looking at a 2007 World Health Organization bulletin looking back at his work. In it, we get an immediate excuse as to why Sir Ross was unsuccessful in his endeavors for two years while trying to find the malaria parasite in mosquitoes. He was working with what we now “know” to be insusceptible mosquito species. When he was able to eventually find “novel objects” in the stomachs of only two brown mosquitoes, the WHO admits that his paper was submitted and accepted to the The British Medical Journal - without appropriate controls, such as mosquitoes from the same source fed on a crescent/gametocyte-negative volunteer, and without replication. The WHO bulletin even posed the question: What hope would it have of getting past the editor and reviewers [today]? The WHO characterized the study as “hardly conforming to the concept of a controlled and replicated study.” Fortunately for Ross, much like the journals of today, the editors of The British Medical Journal in 1897 did not care that the work lacked basic scientific requirements in order to be published:

Malaria, mosquitoes and the legacy of Ronald Ross

“In 1895, Ronald Ross was based in Sekunderabad, India, where he embarked on his quest to determine whether mosquitoes transmitted malaria parasites of man. For two years his studies were clouded by observations on what we now know to be insusceptible mosquito species. He nonetheless observed “flagellation” of Plasmodium in the bloodmeal of these insects, the true nature of which was revealed by McCallum in 1897.1 Ross’s later work also benefited from the numerous observations on insects infected by other parasites (including helminths, fungi and gregarines) he made in this early phase of his quest for the malaria vector. Eventually in July 1897 he reared 20 adult “brown” mosquitoes from collected larvae. Following identification of a volunteer (Husein Khan) infected with crescents of malignant tertian malaria and the expenditure of 8 annas (one anna per blood-fed mosquito!), Ross embarked on a four-day study of the resultant engorged insects. This “compact” study was written up and submitted for publication.

Imagine today sending an article to a leading medical journal in which you describe observations on novel objects found on the midguts of just two “brown” mosquitoes, obtained from larvae of natural origin, that you had previously fed on a naturally infected patient – with no appropriate controls and no replicates! What hope would it have of getting past the editor and reviewers? Thankfully, Ronald Ross’s paper was more fortunate: it was published by the British Medical Journal on 18 December 1897.2 His conclusions were understandably modest. “To sum up: The [putative malarial] cells appear to be very exceptional; they have as yet been found only in a single species of mosquito fed on malarial blood; they seem to grow between the fourth and fifth day; and they contain the characteristic pigment of the parasite of malaria.” So begins one of the most influential stories for malaria research and control.”

“There were, however, no controls, such as mosquitoes from the same source fed on a crescent/gametocyte-negative volunteer. In this regard Ross excuses himself, stating “I have not yet succeeded in obtaining any more of the species of mosquito referred to,” and felt it was adequate to describe results from other mosquito species (including a genus Aedes now known to be refractory to infection by P. falciparum) fed on different volunteers. While hardly conforming to the concept of a controlled and replicated study, Ross commendably obtained, and reported fully, a second opinion on the nature of the preparations from Surgeon-Major John Smyth, whose comments are very detailed.”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2636258/

As can be seen, the two pivotal pieces of information regarding the causative role of a plasmodium parasite in the non-specific symptoms of disease labelled as malaria, i.e. that of the discovery of the parasite itself by Laveran as well as finding the parasite in mosquitoes by Ross, are of a highly questionable nature. Even if we were to accept that what was found by Laveran is a parasite, does this mean that it is a causative agent of disease? In order to answer this, let’s turn to Koch's Postulates, the necessary logical requirements that must be fulfilled in order to establish that any microorganism can cause disease. Let's examine each postulate briefly and see how the plasmodium parasite holds up:

1. The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organisms suffering from the disease, but should not be found in healthy organisms.

According to the WHO, the vast majority of those who are diagnosed with the plasmodium parasite have few, if any, symptoms:

Malaria Pathogenesis

"When we turn to the parasite inside the human host, only a small number of these morphological stages lead to clinical disease and the vast majority of all malaria-infected patients in the world produce few (if any) symptoms in the human (WHO 2015)."

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5749143/#A025569C77

Asymptomatic malaria is commonly seen, with one study showing a prevalence rate of 55% with another showing 67% of the cases classified as asymptomatic. A study from May 2020 stated that the majority of the population in malaria endemic areas (>60%) is asymptomatic (without overt symptoms), even in high transmission areas. In a 2013 review, it was found that seven studies reported 73–98% of the P. falciparum infections to be asymptomatic, while five studies reporting on P. vivax found 64–100% of infections to be asymptomatic.

It is admitted that using the simple microscopic test in order to diagnose malaria has a pretty significant drawback. In patients who live in endemic areas, malaria infections may be asymptomatic and of little clinical significance. It is said that finding the presence of parasites in such patients cannot be assumed as the cause of the symptoms of an illness, which may have other causes. In other words, finding the parasites within an individual does not mean that the parasite will cause or is the cause of future disease. In such cases, there is currently no diagnostic to associate malaria infection with disease.

It can be seen that the majority of those identified with the plasmodium parasite are symptom-free and entirely healthy. Going back to Laveran, remember that he claimed that the parasite is only found in those with disease, which led him to believe it to be the causative agent of malaria. This is patently false. Also, recall that Laveran admitted that he could not find the assumed parasite in all cases of the disease. Thus, it is clear that the plasmodium parasite cannot fulfill the very first of Koch's Postulates as it is not found in all cases of the disease, and it is regularly found in those who are healthy.

2. The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture.

This one is fairly straightforward. In 1996, Fredericks and Relman summarized the problem in an article in Clinical Microbiological Reviews:

“Organisms such as Plasmodium falciparum and herpes simplex virus or other viruses cannot be grown alone, i.e., in cell-free culture, and hence cannot fulfill Koch's postulates, yet they are unequivocally pathogenic.”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8665474/

Even if it was able to get past the first Postulate, as the plasmodium parasite can not be grown in pure culture, it cannot satisfy the second of Koch's Postulates.

3. The cultured microorganism should cause the same disease when introduced into a healthy organism.

It is clear that neither Laveran nor Ross successfully proved that the plasmodium parasite was able to cause the disease they associated it with as neither researcher even attempted pathogenicity studies. Thus, we are left to the proceeding decades to see if these studies were ever carried out in order to successfully establish an experimental model recreating the disease seen in humans. Going by a review of the experimental models up to 2011, it appears that this was never successfully established using proper experiments in accordance with the scientific method. It is stated that when investigating human malaria, the studies show an association and cannot conclude causality. The studies are observational research on humans who “naturally acquire” malaria, and these studies are criticized as inconclusive. It is said that the lack of access to relevant organs and tissue samples, as well as the inability to manipulate the “immune response” when performing mechanistic studies, are major limitations hindering the study of human malaria. Increased funding along with repositories of human samples and clinical data are needed in order to confirm hypotheses in this human disease. It is stated that this lack of access to human samples often precludes the opportunity to validate findings in existing animal models, thus their relevance remains unproven. In order to identify which models best approximate human infection and disease, it was agreed that human and animal researchers must work together to find a suitable solution:

"Although the major focus of the ensuing discussion was animal models, Nick Anstey (Menzies School of Public Health, Darwin) pointed out that researchers have faced similar challenges when seeking support to investigate human malaria, which often entails studies of association that cannot conclude causality. For this reason, observational research on humans who naturally acquire malaria is sometimes criticized as inconclusive, with the consequence that funding and publication are impeded in this area. Despite these criticisms, studies of malaria in humans are clearly desirable, but many limitations, such as the lack of access to relevant organs and tissue samples, and the inability to manipulate the immune response for mechanistic studies, mandate additional approaches, where animal models may be most appropriate. Furthermore, all meaningful studies on human malaria require appropriately documented samples, which are not always readily available to the global research community."

"A consensus of the attendees was the need for funding to establish repositories of human samples in conjunction with carefully collected clinical data, as these would offer invaluable resources to confirm hypotheses in the human disease. This lack of access to human samples often precludes the opportunity to validate findings in existing animal models, thus their relevance remains unproven. Closer collaborations between scientists performing human studies and those performing animal studies are needed to find parallels and differences between these research approaches, to identify which models best approximate human infection and disease."

https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2875-10-23

Another study noted that the observation of “infected” humans can not answer critical questions related to malaria. In fact, it noted that the exact mechanisms whereby malaria parasites cause severe disease remains unknown. The authors stated that it is unlikely that any single model will reproduce the complexity and spectrum of disease observed in human malaria “infections.” They also noted that the spectrum of disease in humans is broad and, due to this, we are not able to fully understand the pathological mechanisms of malaria. The key recommendation was that the development and standardization of animal models was a priority.

Thus, without being able to prove causation with human or animal experiments in order to confirm the hypothesis that the plasmodium parasite causes the symptoms of disease it is associated with, it is clear that the plasmodium parasite also fails not only Koch's third Postulate, but also the fourth one as well:

4. The microorganism must be reisolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

Malaria is just another label for the exact same symptoms seen year-round all over the world. These symptoms are presented back to us with different names, causal microorganisms, and treatments. Diagnostic criteria cannot clinically distinguish between these diseases, thus the necessity for PCR and other fraudulent tests in order to supply the label and perpetuate the lie. This is why Christopher Shingler was at first either a “Covid” patient or one who had the non-specific “viral infection” tag, and was later able to be changed to a victim of a mosquito-born parasitic attack. They can easily change the diagnosis for the same symptoms based upon non-specific evidence such as finding “parasites” in the blood that are also seen in healthy humans. How many “Covid” cases or “viral infections” could be changed to a malaria diagnosis here in the US if everyone was checked for the plasmodium parasite? How many asymptomatic “infections” would be found upon mass testing?

Beyond these glaring issues, when one investigates the history of malaria, it is clear that the scientific evidence proving the causative agent does not exist. Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran was unable to show that the plasmodium parasite he discovered caused the symptoms of disease known as malaria. Sir Ronald Ross failed to do the same with the pigmented cells he found in mosquitoes. The plasmodium parasite is regularly found in those without disease as well as not found in all cases of those with the disease. It cannot be grown in a pure culture, and the evidence for causality is based upon observational studies rather than experimental evidence derived from the scientific method. Neither man fulfilled Koch's Postulates in order to prove that the plasmodium parasite was the causative agent of disease. Neither man followed the steps of the scientific method in order to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. The very foundations holding up the fictional narrative that mosquitoes are able to cause disease via the plasmodium parasite is made up of rotten-to-the-core wood ready to cave under the immense amount of pseudoscientific pressure being piled on top.

goes notarized with her excellent Freedom of Information requests. examined the epidemic of fake research flooding the “sciences.” investigated the ridiculous claim that diabetes is linked to “Covid.” had an entertaining look at Fan Wu's “SARS-COV-2” paper and the odd timeline surrounding it. examined whether the CDC was manipulating death certificates. provided insight into the recent Joe Rogan and Robert Kennedy Jr. podcast in his latest. knocked it outta the park yet again with this takedown of the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer.

And to back up Mike's wonderful article...

December 5, 2022:

Roger Andoh acting as FOIA Officer in the Office of the Chief Operating Officer, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention failed to provide or cite any record that describes controlled experiments proving that parasites cause malaria. Instead, Roger cited 5 irrelevant/unscientific papers.

Very briefly:

1st paper, Studies on Human Malaria….

– small sample size, no controls, invalid independent variable, not even designed to test for causation of malaria

– monkeys were inoculated intrahepatically with crushed mosquito salivary glands and monkey serum-saline, as well as intravenously with supernatant from centrifuged crushed mosquito bodies (minus salivary glands) and monkey serum-saline

2nd paper, Chloroquine Resistant…

– small sample size, no controls, invalid independent variable, not even designed to test for causation of malaria

-infected blood from a human was innoculated intravenously into 1 splenectomized monkey, then blood from that monkey was subpassaged into other splenectomized monkies, etc

The remaining papers are equally irrelevant and unresponsive. See for yourself:

https://www.fluoridefreepeel.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/CDC-parasites-causing-malaria-PACKAGE-redacted.pdf

Excellent summary! Interesting that a dewormer, ivermectin, supposedly cures “Covid“.