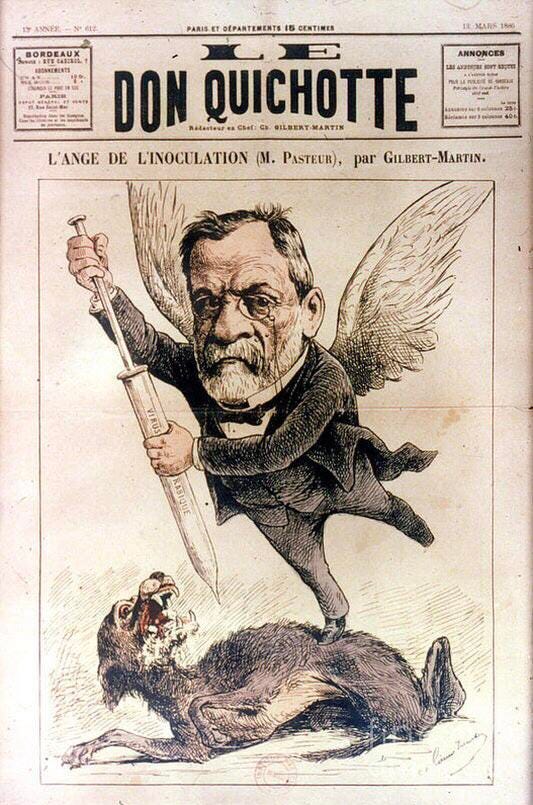

Pasteur's Method of Treating Hydrophobia

Utilizing popular fears and fantasies to impose new "medicines."

On December 15, 2023, I announced that I had begun the early stages of writing a book—something I had always dreamed of doing. With the wealth of material from both of my sites, I could have easily reformatted my existing work into one. However, I wasn’t content with simply repackaging old articles. If I was going to write a book, I wanted to dig deeper, presenting not just my previous research but also new evidence and fresh insights. What began as a short introductory booklet exposing the fraud of virology has since evolved into something much larger. To do this right, I felt it was necessary to trace the origins of the germ “theory” of disease and explore how it laid the foundation for virology as a subsidiary field.

As such, I have been conducting a more nuanced and detailed examination of Louis Pasteur’s work. Some of this research made its way into my article The Germ Hypothesis Part 1: Pasteur’s Problems, where I analyzed his experiments on chicken cholera, anthrax, and rabies. As I expanded on these areas for the book, I developed an even greater appreciation for just how fraudulent and deceptive his research truly was—especially regarding rabies. While I have written about rabies in the past—specifically about it being a “virus” of fear—it always seems that there is more underneath the surface left to discover. In fact, there is enough material on rabies alone to fill an entire book, making it particularly challenging to condense everything into just a portion of a chapter on Pasteur.

Fortunately, while researching this section, I came across what I consider to be one of the most concise and damning critiques of Pasteur’s rabies experiments. This critique was presented before the Philadelphia Medical Society by Dr. Charles Winslow Dulles on January 13, 1886. The introduction by the Victoria Street Society, united with the International Association for the Protection of Animals from Vivisection, described Dr. Dulles’ analysis as the most effective criticism of Pasteur’s hydrophobia treatment they had ever encountered. They noted that Pasteur’s own explanations were “lacking in the essential elements of cohesion, consistency, and clearness.”

INTRODUCTION.

THE following important paper forms by far the most effective criticism which we have yet seen on the Pasteurian theory of inoculation for hydrophobia. It is from the pen of an American medical man, who has evidently read the whole series of M. Pasteur's expositions of his system in the original Bulletins, and it will be seen that the result of this careful professional examination is to show that the explanations even from Pasteur's own mouth are lacking in the essential elements of cohesion, consistency, and clearness.

The paper of Dr. Dulles was originally read before the Philadelphia Medical Society, on the 13th of January last.

As I also find this paper to be a highly effective critique of Pasteur’s research, I am presenting it here in its entirety. However, to further clarify key points made by Dr. Dulles, I have included additional commentary and supporting evidence throughout. Hopefully, by the end, Pasteur’s fear-based fraud will be even clearer for all to see.

When Dr. Charles Winslow Dulles gave his presentation Pasteur's Method of Treating Hydrophobia to the Philadelphia Medical Society, he began by presenting a resume of Pasteur's rabies communications up to that point. The paper, however, begins by presenting his critique of Pasteur's seventh communication on rabies from October 1885, one of his last on the subject. According to leading Pasteur historian Gerald Geison's book The Private Science of Louis Pasteur, up to that point, Pasteur had provided only “brief and tantalizingly vague” (Geison, 189) accounts of his rabies research. However, his October 1885 address before the Académie des Sciences was an immediate sensation that has since been enshrined in legend (Geison, 193).

In this communication, as Dr. Dulles pointed out, Pasteur immediately admitted that his previous vaccination method described in prior communications rendered only 15 or 16 out of 20 dogs “refractory” to rabies. He also acknowledged that determining refractoriness—i.e., “immunity”—required no less than three or four months, significantly limiting the number of experiments he could conduct. Dissatisfied with these results, Pasteur devised an alternative approach.

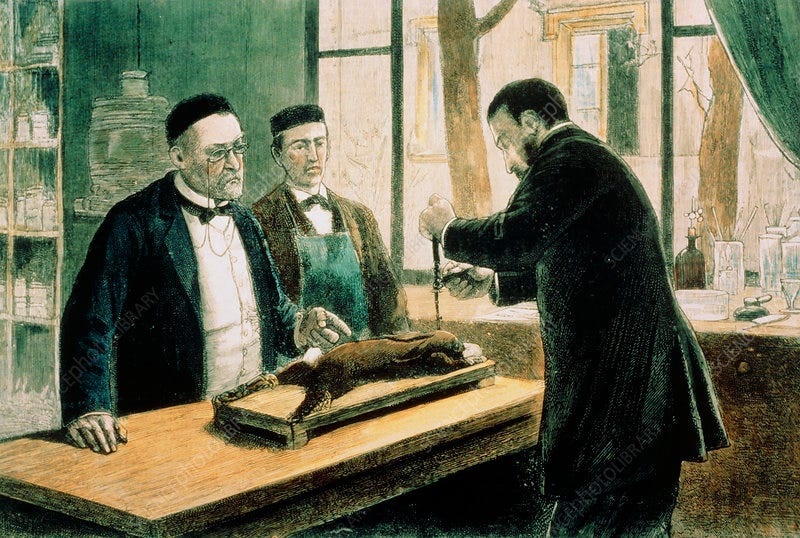

This new method involved trephination—removing a circular piece of bone from the skull—and injecting spinal cord material from a rabid dog directly into a rabbit’s brain. Once the rabbit succumbed, its spinal cord was harvested and injected into another rabbit in the same manner, with the process repeated multiple times. Eventually, the spinal cord from the final rabbit was removed and left to dry—a procedure Pasteur claimed reduced its “virulence.”

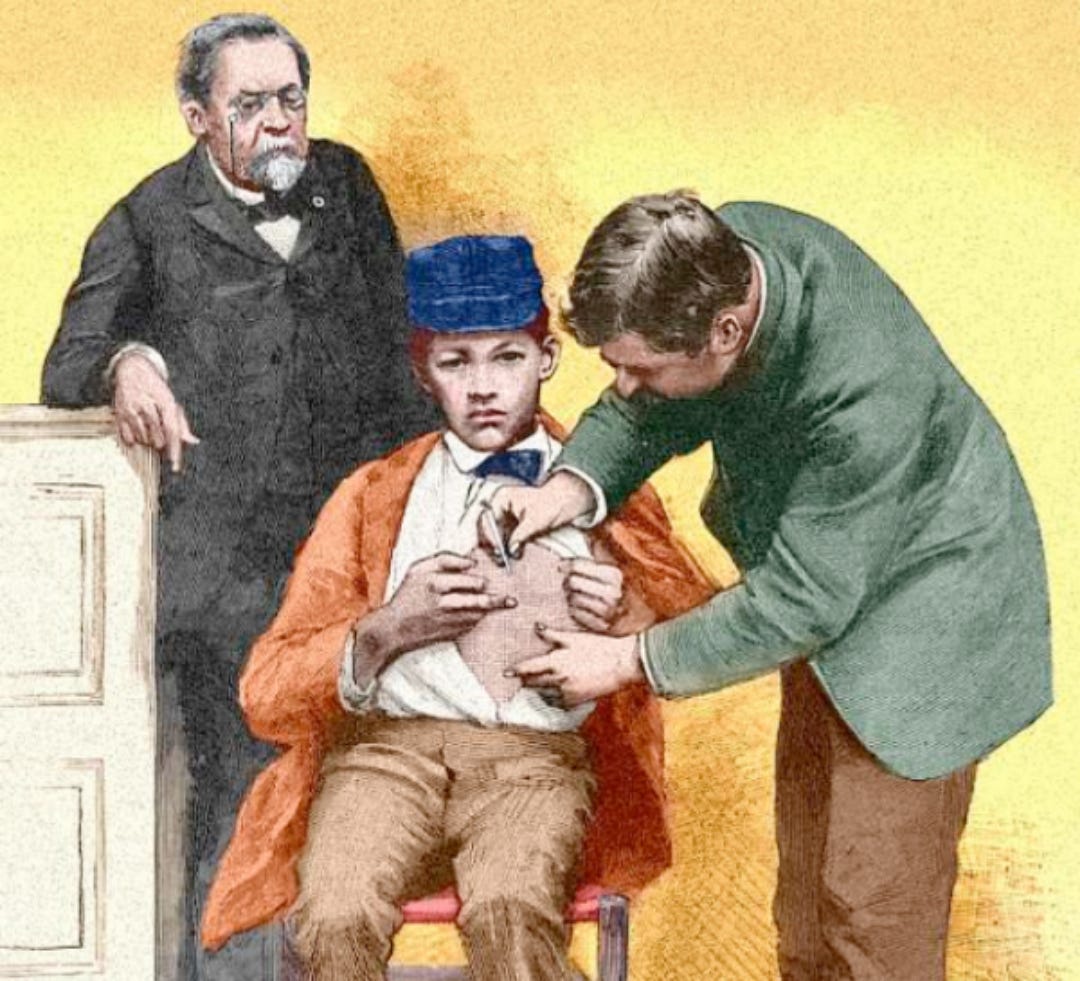

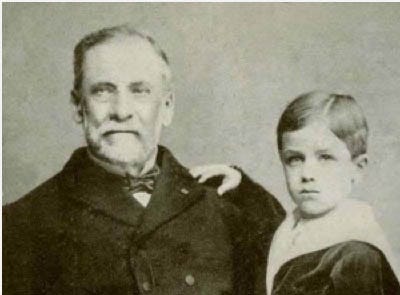

Once aged, a small piece of the dried spinal cord was dissolved in sterilized veal broth and injected subcutaneously into a dog using a Pravaz syringe. Dr. Dulles noted that the criteria for determining the optimal aging of the spinal cord were known only to Pasteur and his collaborators. This was the method utilized to create the treatment purportedly used on Joseph Meister, the 9-year-old boy Pasteur famously claimed in this address to have saved from a fatal case of rabies after multiple dog bites. However, as Dr. Dulles highlighted, Meister’s wounds had already been cauterized—the primary “cure” for rabies at the time—and the dog was diagnosed as rabid based solely on an autopsy finding that its stomach contained hay, straw, and bits of wood.

Pasteur's Method of Treating Hydrophobia

DR. DULLES first gave a resumé of Pasteur's communications. We give the last part of the discourse. Dr. Dulles said:- “Pasteur's seventh and last communication on this subject is boldly entitled, “Methode pour prévenir la rage après morsure” (Bull. de l'Acad. de Méd., October 27, 1885, pp. 1431-39). In this, after a complacent announcement of the value of his earlier discoveries, he confesses that his previous method would only render refractory to rabies fifteen or sixteen out of twenty dogs. To ascertain the fact of refractoriness requires not less than three or four months, he says, which restricts very much the application of the method-and, I may add, indicates how few experiments he could have carried out to their conclusions.

He had, therefore, attempted to discover a method which he could dare to call perfect. “After experiments, so to speak, innumerable, I have,” he says, “discovered a preventative method, which is practical and prompt, the successful applications of which to dogs are already numerous enough and sure enough for me to have confidence in its general applicability to all animals and to man himself” (loc. cit., p. 1432).

This method may be summarised as follows:- An attenuated virus is obtained by inoculating a rabbit, by trephining, with rabic spinal cord of a dog dying of ordinary rabies (rage des rues), and then a second rabbit with the spinal cord of the first and so on in series. After a very long series it is found that a “virus” is obtained which kills rabbits in seven days. When this point is reached, pieces of the spinal cord of one of the victims are removed with precautions of purity as great as it is possible to secure, and suspended in small flasks in which the air is kept dry by a piece of caustic potash. With each day that it is kept such a piece of spinal cord becomes less virulent.

The treatment consists in taking a small piece of one of these cords and “dissolving” (délayer) it in sterilised veal broth, and injecting a Pravaz syringeful under the skin of the dog. The age of the cord used must be such that it does not endanger the life of the subject of the experiment. How to ascertain the proper age Pasteur says he knows from experience; but unfortunately he forgets to say how anyone else may decide the matter (loc. cit., p. 1433). The effect of this treatment Pasteur, when he made his report, had tried on one human being, the now famous Joseph Meister, nine years old, bitten July 4th by a dog supposed to be mad. His bites were numerous. The principal ones had been cauterised the same day with carbolic acid. At an autopsy the dog's stomach was found to contain hay, straw, and bits of wood; and on this fact alone the diagnosis of rabies in the dog rests to this day. Pasteur called Dr. Vulpian and Dr. Grancher to see the boy, and they said he was most inevitably exposed to contract hydrophobia, on account of the severity and the number of his bites.

Interestingly, Pasteur relied on Drs. Alfred Vulpian and Emile Granger to examine and treat the young Meister rather than his most trusted collaborator, Emile Roux. This was because Roux had a “clear appreciation of just how boldly, even recklessly, Pasteur was willing to apply vaccines in the face of ambiguous experimental evidence about their safety or efficacy” (Geison, 237).

While working on the rabies vaccine, tensions between the two nearly led to a permanent rupture. Their disagreement centered on how much reliable evidence should be gathered through animal experimentation before it became ethical to proceed with human trials. Unlike Pasteur, Roux was a qualified medical doctor, fully licensed to practice medicine. He could have administered the so-called “life-saving” injections to Joseph Meister, yet he was noticeably absent from the entire ordeal (Geison, 238)

Geison suggested that Roux’s absence was likely due to his belief that Pasteur’s treatment of Meister constituted unjustified human experimentation (Geison, 238). As someone intimately familiar with the extent of both the animal and human experimentation conducted—as well as its success, or lack thereof—Roux clearly deemed the evidence insufficient to justify treating the young boy (Geison, 238–239). As such, he reportedly refused to sign the work on the rabies vaccine.

Meister received a half-syringeful of fifteen-day-old spinal cord, followed by twelve additional injections over the next ten days, with increasingly fresh and supposedly more “virulent” materials. Because he did not succumb to the disease—even after receiving materials purportedly more “virulent” than the bite of a rabid street dog—the boy was considered “cured.” Pasteur's notebooks revealed that the last three “virulent” inoculations were not necessary to “cure” young Meister. In a highly unethical move, he had them performed in order to test the “effectiveness” of his method by deliberately attempting to “infect” (i.e. poison) the child with the rabies “virus” to demonstrate that the vaccine prevented further “infection.”

Dr. Dulles noted that Pasteur's evidence was inadequate. There was no proof that the dog that had bitten the young Meister was ever rabid, and since his wounds had already been cauterized, there was no reason to assume that the boy would have succumbed to the disease. Even if he had been in danger of becoming ill, Dr. Dulles argued that it was far too early for Pasteur to claim success.

“The death of this child appearing inevitable,” Pasteur then decided, “not without keen and cruel solicitude,” to try his new method on him. He inoculated the boy with a half syringeful of spinal cord (he says, meaning no doubt diluted or délayé) fifteen days old. He made in all twelve hypodermic injections in ten days, each day using a fresher cord, and then sent the boy home cured, having “escaped not only the hydrophobia which his bites might have developed, but that with which I had inoculated him, to test the immunity due to the treatment, a hydrophobia more virulent than that of street dogs” (loc. cit., p. 1436).

In commenting upon this communication there are two sets of objections raised. One relates to the case of the boy Joseph Meister, which has attracted such attention the whole world over. The other relates to the general statements made, regarded from a scientific standpoint.

In regard to the case of the boy, it may be briefly stated:-First, because there is no proof that the dog that bit him was mad (everybody ought to know that the contents of a dog's stomach are of no value as evidence of rabies), and because the boy's wounds had been cauterised, there is not reason to assume that he was in danger of having hydrophobia; and, secondly, if he was, it is by far too soon to say he is free from danger.

Dr. Dulles noted that Dr. Jules Guérin, a French physician and surgeon known for his work in orthopedics and anatomy, immediately opposed Pasteur's evidence, although his protest was ignored by the President of the Académie de Médecine. While Pasteur boasted of having conducted innumerable experiments, he never provided exact numbers or detailed accounts. According to Dr. Dulles’ calculations, for Pasteur to have performed uninterrupted chains of successful experiments, he would have needed approximately 130 to 140 rabbits and a continuous period of two and a half to nearly three years without any interruptions or failures. Dr. Dulles questioned the plausibility of such an experimental record and the trustworthiness of Pasteur's claims. Moreover, he pointed out that in the only detailed account of these experiments, Pasteur had admitted that half of the spinal cords used in the critical experiment on Joseph Meister showed no evidence of “virus” when tested on rabbits. Out of eleven spinal cords, five were found to be without the “virus,” five were deemed “virulent,” and Pasteur provided no information about the final one.

Dr. Dulles discussed the inconsistencies and contradictions in Pasteur's statements over time, remarking that “they are so inconsistent that the cordial acceptance of almost any one of them seems to demand that the preceding ones should be banished from our memory.” He highlighted several of these inconsistencies, culminating in Pasteur's claim that the protective character of his “virus” depended on a reduction in quantity rather than a reduction in its “virulence.” This directly contradicted his earlier statements regarding his chicken cholera vaccine. Dr. Dulles questioned how Pasteur could reconcile a method that used reduced quantities of “virus”—which initially appeared to cause severe disease—with later claims that the same method was now “protective.” In doing so, he suggested that there were significant flaws in Pasteur's experimental design and interpretation of the data.

When we come to compare the assertions in this communication with the evidence in support of them, we do not wonder that the prudent Jules Guérin begged the unwilling President to let him utter a word of protest before this announcement should go out to the world with the sanction of the Académie de Médecine. As usual, Pasteur, in this communication, speaks of his last experiment as “always” successful (loc. cit., p. 1432). Again, his experiments have been “innumerable, so to speak.” Unfortunately, here as elsewhere (with one exception), the actual number is not named, and his vague statement will bear analysing. The conclusions at which he has arrived could only properly rest on a number of uninterrupted series of experiments, each complete and successful from beginning to end. Now, I have taken the trouble to figure out what a single series would involve, and I find it means no interruption and no failure in experiments requiring one hundred and thirty or one hundred and forty rabbits, and a period of from about two and a half to nearly three years! An interruption anywhere would break up a whole series. Now-supposing no interruption occurred-how many such series could Pasteur have been carrying on during the three years since, he says (loc. cit., p. 1432), he began them? Again, what seems to me the most fatal objection to the idea that Pasteur's experiments could possibly have been trustworthy throughout these immense series is the fact that, by his own admission, a full half of the spinal cords, used in the crucial experiment on Joseph Meister, which gave him such “cruel inquietudes”-as well it might-proved to have no virus when tested on rabbits! Out of eleven, he says, five were without virus, five were virulent; and of one, singularly enough, he says nothing (loc. cit., p. 1436). If this could happen in the only detailed experiment which Pasteur has ever recorded, and when everything seemed to depend upon the infallibility which Pasteur has so often claimed, what are we to think of the experiments done in the secrecy of his laboratory, of which no record has ever been given, and of which not a single witness has ever spoken except Pasteur?

Another matter to be remarked just here is that until now Pasteur had given no hint that the virus of hydrophobia could be attenuated so simply as by dessicating the spinal cord. And yet, if his own statements are true, he must have been far advanced in his experience with this method at the very time when he was startling the world with his backward and forward modifications of the virus in monkeys and rabbits, and presenting this as the way to obtain the virus for what he called his three little inoculations. If we take the trouble to place side by side Pasteur's statements at different times, we see that they are so inconsistent that the cordial acceptance of almost any one of them seems to demand that the preceding ones should be banished from our memory. At first it was in the brain that the virus was to be obtained in perfect purity; then trephining and intradural inoculation was the sovereign method; then intravenous inoculations were said to simplify the matter; then blood was a good virus; then smaller quantities produced fiercer rabies; then inoculations in series modified the virus after many variations; then a few monkeys and rabbits did the work; then rabbits alone sufficed, while the virus was weakened by drying the cord. And, to crown all, forgetting the traditions of his own work in regard to charbon and chicken cholera, Pasteur says that the protective character of his virus depends upon a reduction in quantity and not in the virulence of the virus (loc. cit., p. 1437).

What! And when we catch our breath, we cannot but recall what has gone before, and say: If the hypodermic injection of reduced quantities of virus was the means Pasteur found would most readily produce the most furious form of rabies, in February, 1884, when he must have been half-way through the series of experiments upon which the present communication rests, how could the remaining half have sufficed to show that the same way of proceeding would exert a kind and protective influence on the same animals and on men?

It’s worth noting that while Pasteur believed he was working with the causative agent of rabies, he openly admitted that he was never able to isolate one. As French physician and Pasteur biographer Patrice Debré wrote in his book Louis Pasteur, Pasteur repeatedly tried in vain to cultivate a rabies microbe for isolation. Realizing that this was impossible, he became obsessed with finding a way to halt the march of his “invisible enemy.” Debré even praised Pasteur for being “able to hold on to his conceptions in the face of an exception that invalidated them” (Debré, 415). Because Pasteur expected to find a “virus”—which referred to a poison or miasma at the time—Debré noted that he simply “divined the virus,” never questioning its existence despite its invisibility (Debré 414).

However, this suggests a clear case of confirmation bias, where Pasteur’s expectations shaped his interpretation of the evidence rather than allowing the data to guide him independently. He was predisposed to assuming a microbial cause for rabies and never rigorously tested alternative explanations. Instead, he engaged in begging the question—assuming a microbial cause existed and then treating his inability to cultivate it as proof of its “invisibility” rather than reconsidering his premise.

As Dr. Dulles pointed out, Pasteur ultimately rationalized his contradictory results by proposing that his “invisible enemy” was actually two distinct substances: one animate, which germinated in the nervous system, and one inanimate, which arrested its development. Rather than acknowledging flaws in his hypothesis, Pasteur created a fictional narrative of competing substances to reconcile his failed attempts at isolation with his unwavering belief in a microbial cause.

But I must close my comments on this communication with the latest of Pasteur's theories. He actually intimates that the virus of hydrophobia “may be formed of two distinct substances, and that by the side of one which is animate and capable of germinating in the nervous system, there may be another, inanimate, having the power, when in proper proportions, to arrest the development of the former” (loc. cit., 1438).

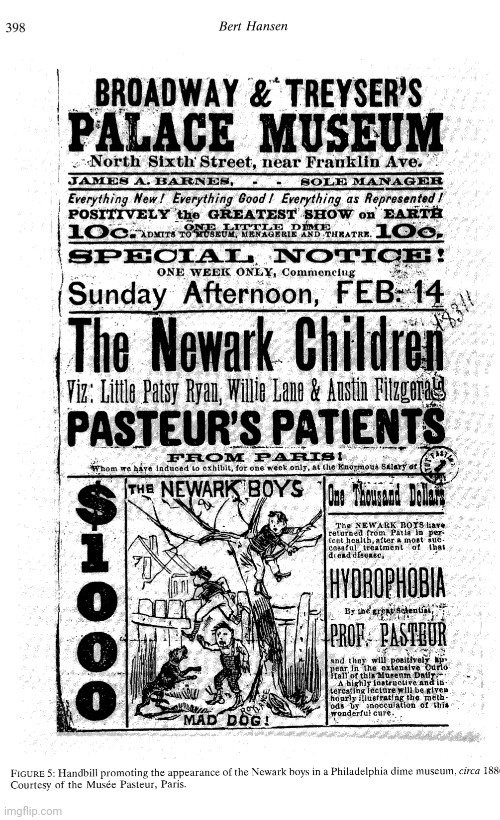

Dr. Dulles then examined the contradictory evidence surrounding Pasteur’s rabies cases after Joseph Meister. One notable incident involved four boys from Newark, New Jersey, who were allegedly attacked by a rabid dog. A fundraising campaign—backed by figures like Andrew Carnegie, a key promoter of germ “theory” in America and an architect of the allopathic takeover of our medical system—sent the boys to Paris for Pasteur’s treatment. Afterward, they were paraded around as proof of his “cure,” showcased as living advertisements to promote his success.

However, as Dr. Dulles pointed out, there was no evidence that the dog that attacked the boys was rabid to begin with. In fact, the four boys were not the only ones bitten—two other boys were also attacked yet remained disease-free despite not receiving Pasteur’s treatment in Paris. Notably, Dr. Dulles did not mention that four dogs were also bitten by the supposedly rabid dog, yet none of them developed the disease either.

Dr. Dulles also highlighted the tragic case of a 10-year-old girl who received Pasteur's treatment—Louise Pelletier. According to Rene J. Dubos's Louis Pasteur: Free Lance of Science, she was brought to Pasteur on November 9, 1885, 37 days after being bitten on the head by a mountain dog. Believing that such a delay often led to fatal outcomes, Pasteur was reluctant to treat her, as she had not yet shown any symptoms of rabies. However, at the pleading of her parents, he proceeded with the treatment. On November 27—eleven days after the treatment concluded—the first symptoms of hydrophobia appeared, and Louise Pelletier tragically passed away.

Pasteur excused this failure due to the young age of the girl and the proximity of the bite to the brain. However, as Dr. Dulles pointed out, the facts did not support this belief. According to a report to the Academie de Medicine by Dr. Dujardin-Beaumetz, which Pasteur should have been familiar with as he was a member, cases occurring in the Department of the Seine over the years 1881, 1882, and 1883, showed that there was no relation between the point of inoculation and the period of incubation.

Dr. Dulles pointed out the contradictions in Pasteur's statements, where he stressed on December 8th, after the girl’s death, that he was confident his treatment will be successful if commenced at any time before actual hydrophobia sets in, “even if a year or more elapses between the bite and the commencement of treatment.” However, on January 1st, he asserted that his treatment is efficacious fifteen days after a bite.

Since M. Pasteur made his last communication to the Académie de Médecine and to the Académie des Sciences, the enterprising New York Herald has given much space to discussing his method and its application. We have all heard of the four children sent from Newark to Paris, after being bitten by a dog of which there is not the remotest evidence that it was mad, and of their return to America in apparently as good a state of health as is still enjoyed by the remaining two, who were bitten at the same time by the same dog, and who have never stirred from home. Three other Americans have gone over-viz., a man named Kaufmann, another by the name of Sattler, and a boy named Edward Bucklin. In regard to these patients there is equally little evidence that they have been exposed to the bite of a rabid dog. Indeed, in the case of one of them, it is denied that he was bitten at all. Pasteur is said to have refused to practise on him, and again he is said to have done so. All these seem to have maintained their health in spite of their bites, their fears, their long journey, and their inoculations with Pasteur's weak and strong viruses. One of M. Pasteur's patients, a girl aged ten, died of rabies while under treatment by him. This mishap Pasteur explained by saying she had come to him thirty-six days after being bitten, and that the virus in her system had made too great progress to be stopped. Its rapid action he explained on account of her youth-an assertion which is not borne out by facts-and because she had been bitten on the head, i.e., near to the brain. This latter explanation is in accord with one of Pasteur's theories borrowed from Davaine; but it is also opposed to facts with which he should have been familiar; for, as lately as April 8, 1884, Dr. Dujardin-Beaumetz added, to what was clear enough before to any one who had carefully studied the subject, the confirmation of a report to the Academy of Medicine, of which M. Pasteur is a member, on the cases occurring in the Department of the Seine, in the three years 1881, 1882, and 1883 (thirty-four cases in all), which showed that there was no relation between the point of inoculation and the period of incubation.

On December 8th Pasteur said: “I am confident my treatment will be successful, if commenced at any time before actual hydrophobia sets in, even if a year or more elapses between the bite and the commencement of treatment.” This was on the very day, I believe, on which the little girl died, and suggested to him that thirty-six days was a long time to wait, while on January 1st of this year he says that his treatment is efficacious even fifteen days after a bite!

Dr. Dulles criticized Pasteur for keeping his method a secret, despite claiming that it was simple and practicable. For instance, Pasteur never revealed how much veal broth should be mixed with a given quantity of so-called rabid spinal cord used in his injections. This secrecy meant that no one outside of Pasteur and his colleagues could verify his experiments. As Geison noted, many in the medical and scientific press considered Pasteur to be an “egomaniacal and intolerant representative of ‘official’ science, as well as an unscrupulous, secretive, and greedy opportunist.” Pasteur was so secretive about the direction of his research that even his trusted collaborator, Emile Duclaux, complained of his “Olympian silence.”

The very last utterance of Pasteur on this subject is contained in the statement prepared for the New York Herald, under his direction, by his assistant, M. E. Wasserzug, on January 1st of this year. This embodies a good account of his last method, in which it is noticeable that while he specifies that he uses half a Pravaz syringeful of his mixture of rabic medulla and sterilised veal broth for a child (as compared with three-quarters of a syringeful used for adults), he omits entirely as he has invariably omitted-to say how much of the veal broth is used to mix with a given quantity of so-called rabic spinal cord. This quite material omission is accompanied by two opposite statements: one, that his method is very simple and very practicable; and the other, that outside of M. Pasteur and of his laboratory, there does not exist a single person in the world capable of undertaking the treatment with certainty of success (sûrement).

Dr. Dulles then leveled his harshest criticism at Pasteur, arguing that the so-called “proofs” were nothing more than his unsupported assertions. He pointed out that Pasteur’s claims were not only internally contradictory but also contradicted established facts, some of which he seemed unaware of. Dr. Dulles found no evidence that Pasteur was even familiar with the clinical manifestations of hydrophobia or its history.

A few years before his critique of Pasteur’s work, Dr. Dulles wrote the short 44-page booklet Disorders Mistaken for Hydrophobia, in which he noted that the symptoms of hydrophobia appeared in no fewer than thirty disorders—and likely many more. Rather than acknowledging these cases as misdiagnoses of human rabies, physicians classified them under the vague label of spurious hydrophobia, as if it were a distinct condition. Dulles argued that this term merely created a new category without identifying the true causes of these cases, suggesting that many supposed rabies diagnoses were, in fact, misdiagnoses of other conditions. Dr. Edward Charles Spitzka, an esteemed late-19th century neurologist, agreed with Dr. Dulles, stating, “The resemblance between the spurious hydrophobia and the so-called real affection is so great that I cannot criticise anyone for believing, with Dulles, that the existence of a genuine hydrophobia in man is not proven.”

Dr. Dulles pointed out that Pasteur appeared either ignorant of or willfully dismissive of the research from his own country, never acknowledging whether it had contributed anything of value, nor did he recognize the work of researchers outside France. This lines up with Geison's observations as he frequently noted Pasteur’s obsessive focus on priority. Pasteur spent significant time and effort attempting to establish himself as the first to discover something, thereby securing fame and fortune. This often led him to recreate or slightly modify the work of others and present it as his own, or, alternatively, to dismiss or discredit others’ contributions in favor of his own.

And now when we look back over the whole of M. Pasteur's work in connection with the subject of hydrophobia, how shall we judge it? The final impression is to say the least disappointing. In spite of the distinctness of his assertion and belief that he has solved the problem of the cure of hydrophobia, or of its prevention at any time before its outbreak, when we try to follow the steps by which he has reached this conclusion we find ourselves in bewilderment. We seem to be in a maze, travelling blindfolded, cheered here and there by his assurance that all will be well. At length he seems to say, “Look about you, we are safe!” But when we look about, the safety does not appear. The proofs of it are still nothing but his bare assertions. When we examine these we find they are in part contradictory of each other, while in part they contradict facts of which he does not seem to be aware. When we seek for evidence that he is familiar with the clinical manifestations of what is called hydrophobia, or with its history in past ages, we cannot find it. It does not appear anywhere that he has ever seen a case of this sort or ever studied the descriptions which others have given of it. The same is true in regard to the work of others who have studied hydrophobia experimentally. He seems to be ignorant of, or he wilfully ignores, the labours of his own countrymen, never mentioning one as if he had contributed anything of value to our knowledge of the subject, and being doubtless utterly unaware that anyone outside of France has brought patience, perseverance, and skill to bear upon the intricate problem.

Dr. Dulles highlighted Pasteur’s first failure in rabies research, stemming from his mistaken belief in a “saliva microbe” as the cause of the disease. This embarrassing episode began on December 10, 1880, when Pasteur learned of a five-year-old boy who died a month after being bitten on the face by a supposedly rabid dog. Using a painter’s pencil, Pasteur collected mucus from the boy’s mouth, mixed it with water, and injected the solution into two rabbits—both of which died within 36 hours. Over the following weeks, he used the blood from these rabbits to induce similar symptoms in other rabbits and dogs, identifying a “new” microbe with a figure-eight shape, reminiscent of one he had previously observed in chicken cholera studies.

By January 1881, Pasteur claimed to have discovered “a new disease produced by the saliva of a child dead of rabies” and speculated that the microbe had some “hidden relation” to rabies. However, he acknowledged its distinct physiological properties and pathological effects. Despite referring to it in his notebooks as the “microbe of rabies,” experiments soon revealed that injecting it into animals produced symptoms markedly different from what was considered “ordinary rabies.” Worse still, this microbe was found not only in rabies victims but also in healthy individuals and those suffering from unrelated illnesses (Geison, 182-183).

Dr. Dulles pointed out that proper control investigations would have revealed that neither the saliva microbe nor the symptoms associated with it were new. Pasteur’s announcement was soon discredited in multiple ways, with his fiercest critic being German bacteriologist Robert Koch—the very man later credited with “proving” Pasteur’s germ “theory.” At the time, Koch criticized Pasteur for assuming that all “infectious” diseases are parasitic and caused by microbes. He condemned Pasteur’s flawed approach, arguing that he was looking for the causative microbe in the wrong place—saliva rather than the sublingual glands. Koch emphasized that saliva naturally contains bacteria, including so-called pathogens, even in healthy individuals. Furthermore, he criticized Pasteur’s reliance on impure materials and his choice of test animals, arguing that starting with rabbits instead of dogs led to erroneous conclusions about rabies in canines.

In his 1883 paper Remarks on Hydrophobia, Dr. Dulles highlighted that Pasteur himself soon discovered, through his own experiments, that his excitement over the saliva microbe was premature and mistaken. Pasteur acknowledged that the effects he attributed to “rabietic” saliva could also be produced using the saliva of patients with other diseases—and even that of perfectly healthy individuals. Dulles further noted that these findings were later confirmed through experiments conducted by Sternberg and Formad.

Dr. Dulles also reported in this paper that Dr. Robert White demonstrated his conviction that hydrophobia was not caused by the inoculation of a “virus” present in the saliva of a rabid dog by conducting a series of experiments on various animals—and ultimately, on himself. In all cases, no injurious effects were observed.

As recounted in his 1826 book, Doubts of Hydrophobia as a Specific Disease to Be Communicated by the Bite of a Dog, with Experiments on the Supposed Virus Generated in That Animal During the Complaint Termed Madness, Dr. White inoculated rabbits, cats, and other animals with the blood and salivary secretions of two rabid dogs but was unable to induce disease. He also tested the alleged contagion on himself, stating:

"I have also inserted a portion of the supposed poison on the point of a lancet in my own arm, an experiment I would at any time repeat, but without any effect, not even the slightest irritation succeeding the wound."

Dr. White further acknowledged the work of Mr. John Hunter, who had conducted similar experiments with the same negative results.

The very outset of his work in the beginning of 1881 is marked by a positive announcement of a new microbe and a new disease, and an angry repudiation of the suggestion of Colin that control investigations and experiments would show that neither microbe nor disease was new.

This announcement, however, was soon shown to be erroneous in every part of it. He next adopts the ingenious (but mistaken) notion of Davaine, that the nervous system is the channel, and its centre the goal, of the virus of hydrophobia; for which appropriation of his ideas Davaine soon appeared in the lists against Pasteur, and joined the number of those who have questioned his honesty as well as his ability.

Dr. Dulles criticized Pasteur's secrecy, highlighting that no one outside his laboratory could reproduce his results. In fact, experiments conducted independently of Pasteur directly contradicted his methods and claims about the so-called “rabies microbe.” For example, in his paper How Can We Prevent False Hydrophobia?, Dr. Edward Charles Spitzka demonstrated that rabies and hydrophobia could be induced in dogs by inserting any foreign substance into their brains, not just materials Pasteur deemed “rabid.” Dr. Spitzka used a variety of substances, including soft soap, calf’s marrow, calf’s end, and even the spinal cord of a man who was claimed to have died of rabies. He inoculated the dogs using the same trepanning technique advocated by Pasteur. All of the dogs exhibited symptoms of madness, including “epileptic delirium,” which resembled human rabies. Dr. Spitzka concluded that the “method of demonstrating rabies by direct inoculation of the brain is fallacious” and that rabies diagnoses were being obtained through “misleading methods.”

In another instance, Austrian physician Dr. Anton von Frisch was sent for an internship in Pasteur's laboratory to learn his vaccination method in 1886. He eventually returned to Vienna, bringing with him rabbits that were said to be “infected” with rabies. However, when Dr. von Frisch attempted his own experiments, he was unable to reproduce the results claimed by Pasteur’s team. Unable to verify the vaccine’s efficacy, Dr. von Frisch questioned its usefulness and effectiveness, publishing a critical work titled The Treatment of Rabies Disease: An Experimental Critique of Pasteur’s Method. He remarked, “M. Pasteur has replied to my objections without refuting them; I therefore await with the same calmness the last word on this question. The whole method still has an insufficient experimental basis, and we are not justified in applying it to man.” His conclusion received support from one of Vienna's most renowned doctors, Theodor Billroth.

Dr. Dulles highlighted the work of Pierre-Victor Galtier, whose findings challenged Pasteur’s rigid claims by demonstrating that rabies did not always follow the predictable, fatal course Pasteur described. Galtier also observed the absence of the "rabies microbe" in the nerve centers, reporting that injections of nervous tissue did not consistently produce rabies in recipient animals (Geison, 189).

Dr. Dulles further criticized Pasteur’s claim that the “virus” of rabies resided in the spinal cord, arguing that it was based entirely on Pasteur’s personal interpretation of rabies—an interpretation fluid enough to accommodate nearly all experimental outcomes. Pasteur asserted that one part of the spinal cord might contain the "virus" while the rest did not, a notion that Dr. Dulles dismissed as “simply absurd.” He saw this as yet another example of Pasteur adjusting his conclusions to fit failed demonstrations. Additionally, Dr. Dulles pointed out that Pasteur, a chemist with no demonstrated diagnostic expertise, relied on the presence of certain granules in brain tissue as a marker of rabies. However, these granules had been described before Pasteur took interest in them and were not exclusive to rabid animals.

A year and a half later, December 12, 1882, Pasteur claims to have discovered that the virus of hydrophobia has its principal seat in the brain, and that it there can be gathered in perfect purity and inoculated with absolute certainty, its effects being “prompt and sure.” We have not time to discuss the theoretical objections to this assertion, which are very many. It is enough to point out that although Pasteur has repeated it many times, it has never been confirmed outside of his laboratory, that it stands opposed to the experiments of a much more candid experimenter, Galtier, of Lyons, and that it is not true of what happens even in Pasteur's own laboratory, for some of his animals recovered spontaneously (Bull. de l'Acad. de Méd., 1883, p. 92).

He next announces the finding of the virus in the spinal cord, often in all parts of it. The evidence of this, as of the preceding assertion, rests upon Pasteur's opinion of what he calls rabies. This we have already seen to be elastic enough to cover almost any result of his experiments, and entirely too elastic to be trustworthy.

Fourteen months after this, Pasteur announced a new doctrine-viz., that when what he calls hydrophobic virus is introduced into the circulation it becomes “fixed” and multiplies, at first in the spinal cord, and that one part of the cord might contain the virus when the rest did not. This is, on its face, simply absurd; but it illustrates the boldness of Pasteur in filling up with an assertion a gap in his demonstrations. This very boldness has misled some who have followed with incautious and uncritical haste the rapid succession of brilliant discoveries announced by Pasteur. For example, when he passes smoothly over an admission that he has never discovered a microbe in his virus, that he is only tempted to believe, in one of infinite smallness from the detection of certain minute granules, by which he claims to be able to distinguish a rabid brain from a healthy one, who pauses to reflect that, on the one hand, he has never demonstrated his skill in this mode of diagnosis; and, on the other hand, that such granules as he speaks of were described before he had thought of them, and are not peculiar to the brains of rabid animals at all?

Dr. Dulles underscored Pasteur’s glaring admission that he had never successfully cultivated his rabies “virus,” a stark contrast to his claims of success with anthrax and chicken cholera. He also criticized Pasteur’s paradoxical assertion that he could induce a more severe and “furious” form of rabies by using a weaker “virus” and in smaller quantities—an idea that defied basic logic, as one would expect a stronger “virus” or a higher dose to produce a more severe disease. Compounding this contradiction, Pasteur also claimed that his protective treatment worked by reducing the quantity—not the quality—of the “virus.” This raised an obvious question: if reducing the quantity of the “virus” led to protection, how could using less of a weaker “virus” result in a more severe illness? If both statements were true, they directly contradicted fundamental principles of cause and effect.

Again, when Pasteur casually admits that he has never been able to cultivate or to isolate what he calls the virus of hydrophobia outside of the body, who calls attention to the relation of this admission to the fundamental principles of his own work in regard to anthrax and foul-cholera? Again, who has lifted up a voice against the contradiction of these fundamental principles in Pasteur's assertion that he could produce the more grave and furious forms of hydrophobia on the sole condition of using a weaker virus, and less of it? And is it not new today, to ask how, if this be true, it can also be true that his so-called protective virus owes its protective character to a reduction in the quantity and not in the quality of the virulent material? or how this last statement can be believed at all?

Dr. Dulles pointed out Pasteur’s flawed assumption that structural similarities imply physiological equivalence, leading him to treat monkeys as suitable substitutes for humans in his experiments. However, Antoine Béchamp had already exposed this reasoning as incorrect in another context. The long and contentious rivalry between Pasteur and Béchamp is thoroughly examined in Ethel Hume’s book, Bechamp or Pasteur? A Lost Chapter in the History of Biology.

Dulles also pointed out that, despite Pasteur’s claims of success, not a single dog had been made “refractory” to rabies outside of his laboratory. He reiterated that, by Pasteur’s own admission, he had only managed to render “refractory” fifteen or sixteen out of twenty dogs. Furthermore, Dulles noted that in Pasteur’s final address in October 1885, he entirely abandoned his theory of using monkeys as part of the process for manipulating his “virus.” Instead, Pasteur presented a new method along with the remarkable claim that the protective character of his “virus” was due to a reduction in quantity rather than quality. He also asserted that his method would prove protective at any time before the outbreak of hydrophobia, even if one or two years had passed since the bite. As previously mentioned, Pasteur held this position until the death of young Louis Pelletier under his supervision led him to reduce this period to thirty-five days, which was later shortened to about fifteen.

The next theory announced by Pasteur was that inoculation of animals in series produced a fixed degree of virulence for each species; and for want of opportunity to experiment on man that monkeys could be considered a suitable substitute. This latter idea shows how Pasteur has been misled by the supposition that similarity of physical structure indicates a similarity in physiological nature-an error which has been admirably exposed (à propos of another matter) by M. Béchamp (Bull. de l'Acad. de Méd., May 8, 1888).

In May, 1884, came Pasteur's announcement that by weakening his virus by transmission through monkeys, and by strengthening it by transmission through rabbits, he had obtained a virus which would prove protective in dogs, and the application of which would eradicate hydrophobia from the world. In regard to this claim, I content myself with a single remark-viz., that in the two years which have elapsed since Pasteur made it, not a single dog has been made refractory to rabies outside of his laboratory; and that in his laboratory he has only succeeded in rendering “refractory,” as he calls it, fifteen or sixteen out of twenty dogs!

The next and last announcement of Pasteur, made last October, was that he had devised a method to prevent the outbreak of hydrophobia after the bite of a mad dog. In this method we find him, without any explanation, dropping entirely the recent theory about monkeys as a part of the machinery for manipulating his virus, and passing by what he had declared to be a simpler mode of operating-viz., by intravenous inoculation to take up hypodermic injection as the method of inoculating, pieces of spinal cord, rubbed up in an unstated quantity of veal broth as a virus, dessication as a means of attenuation, with the astounding explanation that the protective character of his virus was due to a reduction in quantity and not in quality! It seems strange that Pasteur should not have noticed the mutual contradictions of different parts of this announcement; but it is still stranger that he should have failed to see the destructive inference to be drawn from the facts to which I have already alluded-that in his crucial test (in the case of the boy Meister) one half of the inoculation afterwards proved to contain no virus whatever!

Finally, we have Pasteur's positive announcement that his method would prove protective at any time before the outbreak of hydrophobia, even if one or two years had elapsed since the bite, which he stuck to until a case dying under his hands led him to reduce this long period at one sweep to thirty-five days, which was soon after cut down to about fifteen. How soon the short space of fifteen days may be reduced to fifteen minutes we may tremble to contemplate, in view of the rapid rate of reduction which has prevailed thus far.

Dr. Dulles criticized Pasteur for abandoning the belief that the “real virus” of rabies resided in the saliva. Instead, Pasteur opted to use an artificial irritant that never actually caused rabies, but rather induced a peculiar form of septic or inflammatory disease. Dulles pointed out that, being unqualified to properly diagnose rabies, Pasteur arbitrarily labeled his experimental disease as the true one. According to Vaccines: A Biography, rabies diagnoses in the 19th century were based solely on clinical grounds. This, the book suggests, “probably led to diagnostic errors” due to the overlapping clinical manifestations of other encephalitis’s affecting animals. The book also advised caution regarding the many human rabies cases reported at the time. This difficulty in reliably diagnosing rabies clinically is echoed by the WHO, which states that “diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone is difficult and often unreliable.” As Geison noted, there was considerable uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis of rabies, and Pasteur himself acknowledged this, highlighting some of the uncertainties when speaking to the Academie des Sciences about several cases of “false rabies” (Geison, 200).

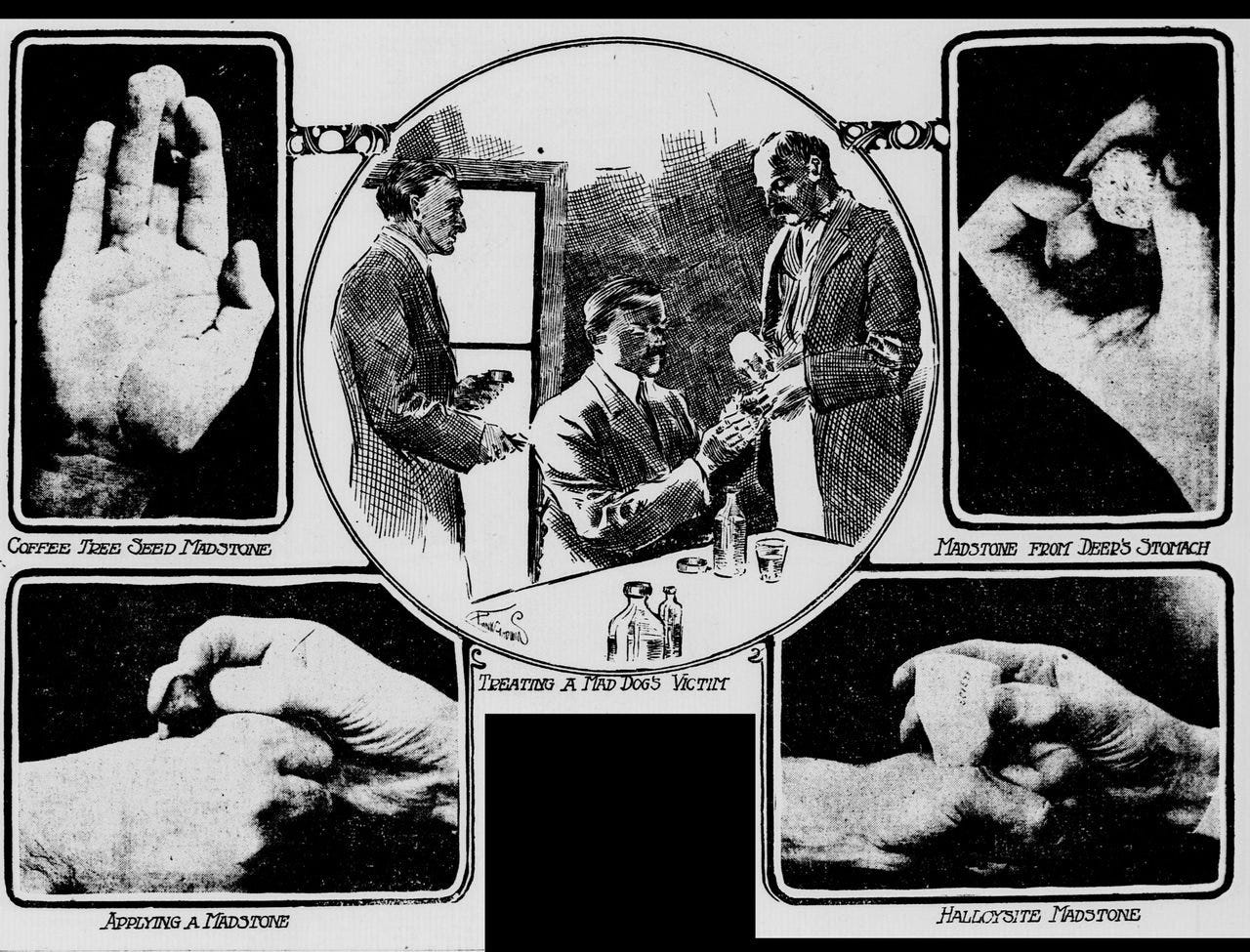

Dr. Dulles also highlighted the ambiguity surrounding the actual success rate of Pasteur's method, suggesting it may have been no more effective than other unproven remedies (“nostrums”) popular at the time, such as the mad stone, which primarily served to alleviate fear. He echoed this concern in his 1883 paper, noting that alongside charms and nostrums, other contemporary “cures” included ducking, bleeding, mercurial saturation, and the administration of violent poisons like large doses of belladonna and prussic acid. Pilocarpine, oxygen, and curare were also employed. As with the deaths attributed to Pasteur's vaccines—later reclassified as rabies fatalities—many of the symptoms and fatalities linked to rabies may, in fact, have resulted from these very treatments. Over time, these iatrogenic effects became embedded in the folklore surrounding the disease.

In this context, Dr. Dulles questioned whether Pasteur's method worked more as a psychological placebo, rather than being truly scientifically validated. He concluded that Pasteur's method was “founded upon untrustworthy experiments and unsound reasoning” and should be “rejected and condemned in the interests of humanity as well as of science.”

One other point must not be overlooked in judging Pasteur's theories from a scientific standpoint, and that is that he has utterly abandoned the only natural virus of hydrophobia, the only one which can be asserted to communicate the disorder from one animal to another-the saliva-and has used an artificial irritant, which probably has never produced rabies at all, but only a peculiar form of septic or simple inflammatory disease, of the significance of which his lack of medical education and experience make him unfit to judge, and which he has quite arbitrarily labelled hydrophobia!

The results of the application of Pasteur's method may be summed up as follows: One death under his hands,* with a lame explanation; over a hundred persons to testify that his inoculations probably do no immediate harm; an almost equal number to illustrate the well-known advantage of having one's fears allayed-in all, no more than is credited to a host of nostrums. Besides which, the excitement it has aroused has brought about a senseless alarm in regard to dogs, and led to the killing of innumerable innocent and unfortunate animals to bear witness to the sharpening of men's fears and the dulling of their judgment.

In conclusion, then, I venture to express my opinion that Pasteur's so-called method of treating hydrophobia before the outbreak does appear to be founded upon untrustworthy experiments and unsound reasoning, and ought to be rejected and condemned in the interests of humanity as well as of science.

While Dr. Dulles was highly critical of Pasteur, describing his “arrogance, impatience of correction, ignorance or disparagement of what others have done; his secret methods, his hasty assumptions, his illogical conclusions,” and how these led to many scientific and personal enemies, he still acknowledged Pasteur’s achievements outside the realm of rabies. Dulles recognized Pasteur's work on ferments and spontaneous generation, which, in his view, immortalized him. Dr. Dulles stated that “he seems to me to deserve all the honor he has received for his unwearied labors and magnificent achievements in the cause of science.”

But while I thus characterise this last work of M. Pasteur, let me not be misunderstood. Here, as in other theories and practices which he has presented to the world, there is much to criticise. Pasteur's arrogance, impatience of correction, ignorance or disparagement of what others have done; his secret methods, his hasty assumptions, his illogical conclusions have made him many scientific and personal enemies. But, after all, Pasteur is the man who placed on a new and apparently secure basis our knowledge of the nature of ferments; who disproved the theory of spontaneous generation; who laid the foundation upon which rests the whole system of antiseptic surgery, for the establishment of which the name of Lister will be justly immortal. Such a man is Pasteur; and, whatever of error may seem to mar some of his best endeavours, and however the future may adjudicate their claims, he seems to me to deserve all the honour he has received for his unwearied labours, and his magnificent achievements in the cause of science.

His very achievements in the right direction, however, make any error on his part all the more dangerous to the cause of truth, and make it all the more the duty of thinking men to sift the evidence upon which he rests his extravagant claim of having discovered a means of preventing the outbreak of hydrophobia.

Thus, Dr. Dulles was not a biased critic seeking to tear Pasteur down. Rather, he believed that Pasteur’s significant achievements made any errors in his work all the more dangerous to the pursuit of truth. This is why Dulles openly challenged what he saw as faulty science and erroneous conclusions from the celebrated chemist.

In the article The Rouyer Affair, Pasteur was quoted as saying that one must “force oneself for days, weeks, sometimes years to fight oneself, to strive to ruin one's own experiments, and to proclaim one's discovery only when one has exhausted all contrary hypotheses” when convinced of an important scientific fact. He described this waiting process as “an arduous task.” However, the article noted that Pasteur repeatedly set aside these principles to achieve his goals.

As Dr. Dulles observed, Pasteur never isolated a rabies microbe. When he initially claimed to have done so, his conclusions were soon proven erroneous. Pasteur's methods of diagnosis were unreliable, and the symptoms attributed to rabies could have been caused by numerous other conditions. Using artificial and unnatural methods, he induced experimental disease that he labeled as rabies. His supposed “successes” occurred in cases where the animal in question could not be reliably shown to have been rabid, nor was there proof that the victim would have succumbed to disease without intervention. In some instances, individuals bitten by the same animal survived without treatment, while others who received Pasteur’s injections later died of the very disease his method was meant to prevent.

Dr. Dulles had many reasons to criticize Pasteur’s experimental evidence—and he was not alone in his criticisms. Yet, over time, the voices of reason—those demanding valid scientific proof for Pasteur's claims—were drowned out and largely forgotten.

Upon retrospective examination, it becomes evident that the symptoms associated with rabies were always rare and nonspecific, often arising from causes unrelated to animal bites. The diagnosis of rabies, both in animals and humans, has historically been unreliable. As historian Gerald Geison noted, there was a “very high degree of uncertainty in the correlation between animal bites and the subsequent appearance of rabies, even when the biting animal was certifiably rabid.” In fact, the vast majority of people bitten by “rabid” animals could forgo Pasteur’s treatment without ever experiencing illness. Moreover, cases presenting with symptoms attributed to rabies were not always fatal and often resolved on their own—especially when the person learned that the biting animal was still alive and healthy. Even in Pasteur's experiments, some dogs injected with a rabies “virus” that was supposedly “virulent” enough to kill others displayed symptoms of rabies yet ultimately recovered.

These inconsistencies suggest that rabies has always been a fear-driven disease, rooted in the nonspecific symptom of hydrophobia and reinforced by the terrifying image of an enraged, frothing animal. Dr. Spitzka quoted a leading American comparative pathologist who observed that humans “often contract a pseudo-hydrophobia as the result of fear, and [it] is curable by moral suasion only.” He further noted, in Pepper’s System of Medicine by American Authors, that extreme heat could “strongly favor the increase of that nervous fear which so often generates a fatal pseudo-hydrophobia (lyssophobia) in persons that have been bitten by dogs.” Many medical writers of the time acknowledged that one of the most difficult conditions to distinguish from so-called “genuine” rabies was fear-induced hydrophobia—a psychological condition rather than an “infectious” disease. In other words, rabies has always been a disease of the imagination rather than a demonstrable “viral infection,” and Louis Pasteur understood precisely how to exploit public fears to advance his own agenda.

Patrice Debré acknowledged that Pasteur skillfully manipulated public fears and fantasies to establish a new form of medicine. Today, based on his questionable claims, it is widely accepted that rabies is an “infectious” disease caused by a “virus,” transmitted from animals to humans through bites, and that it is 100% fatal if left untreated. This belief persists despite contradictory evidence, wildly inconsistent “incubation” periods—sometimes lasting up to 40 years—and numerous cases of people bitten by confirmed rabid animals who never developed symptoms, along with documented instances of spontaneous recovery. The fear-based narrative has been deeply ingrained in public consciousness.

Pasteur’s pseudoscientific methods and toxic treatments were backed by powerful figures, including French Emperor Napoleon III, the wealthy Rothschild banking family (particularly Baron James de Rothschild), industrialists, private donors, and influential businesses. His work conveniently aligned with special interests, ensuring that his findings were promoted as truth, even in the absence of scientific evidence. Fear was all that was needed, as Dr. Spitzka astutely observed regarding the Pasteur Institute’s establishment, “I believe I am doing that institution no injustice when I say that the more hydrophobia scare can be created in the community, the better it will flourish.”

As German physicist Max Planck remarked, “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” Likewise, the rabies narrative has not endured due to scientific rigor—as demonstrated by Dr. Dulles—but because each generation has been conditioned through fear propaganda to accept it without question. With every passing era, the myth becomes further entrenched. It is therefore imperative that we break free from this fear-based dogma before it becomes permanently ingrained beyond challenge.

If you haven't been following

over the last month plus (if so, why haven't you), there has been a lot of great content as is the norm for the dynamic duo! showed how the NIAID failed formal challenges to cite scientific evidence of HPV or monkeypox “virus” existence. looked at how the next “pandemic” has already been arranged. examined how we are being prepared for the next “pandemic” through fear. investigated how reliable AI is at providing accurate answers.

This is a detailed account of the scattershot approach to medical science. Just keep modifying the theory if falsifying results are obtained, speak with authority of unproven conjectures, rely on renowned professional organizations to provide complimentary excuses for shoddy work, and so on. Hydrophobia is more rabies-phobia. As James Joyce wrote, "history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake."

Your continued research and writing are so valuable! Any idea on when your book treatise will be completed?