Kary Mullis: Martyr or Menace?

"You either die a hero, or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain."

Disclaimer: The descriptions of what PCR is supposedly capable of in this article do not reflect my personal views on the technology. My intent is to provide an accurate representation of Kary Mullis’s perspective as the inventor of PCR. By referencing his own words, I aim to clarify how he envisioned its use and limitations, without endorsing or disputing those claims personally.

In 2017, I began my journey that ultimately led to uncovering the lies of virology. At the time, I was lost and searching for answers. The catalyst was the shock of a fraudulent HIV/AIDS diagnosis given to a loved one. Desperate to make sense of it and to support my loved one through the devastation of what felt like a scarlet letter, I turned to the internet for information. I needed to understand how an HIV diagnosis—one that didn’t align with my loved one’s timeline or history—could have happened. Little did I know, this search for answers would challenge and ultimately dismantle everything I believed about “pathogens” and disease.

Initially, I encountered the usual mainstream claims: HIV tests were said to be 99.9% accurate. But I wasn’t content to accept the approved narrative at face value. I needed to understand how such certainty was determined, especially when I knew the diagnosis of my loved one was false. My search eventually led me to a website called VirusMyth.com. It was there that a seed of doubt in virology was planted—one that would grow to change my life forever.

Eager to learn more, I delved into the works of those challenging the mainstream view. The voices of the Perth Group, Dr. Stefan Lanka, David Crowe, Dr. Roberto Giraldo, and others profoundly shaped my views—not only on the accuracy of HIV tests but also on whether HIV itself existed or caused a syndrome called AIDS. Yet, one voice stood out amongst the rest: Kary Mullis, the man credited with discovering polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology, which had become central to the HIV diagnostic process.

I remember being astonished that the inventor of the very technology used to “confirm” positive HIV “antibody” tests not only challenged the entire HIV/AIDS dogma but also believed his invention should never be used as the sole means to diagnose “infectious” diseases. Kary Mullis’s account of his awakening resonated deeply with me. He described his desperate search for a single scientific paper—or even a collection of them—that could definitively prove HIV as the “probable cause of AIDS.” His fruitless quest, including a direct confrontation with HIV “co-discoverer” Luc Montagnier, is detailed in the foreword to prominent retrovirologist and HIV/AIDS skeptic Peter Duesberg’s book Inventing the AIDS Virus.

“In 1988 I was working as a consultant at Specialty Labs in Santa Monica, setting up analytic routines for the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). I knew a lot about setting up analytic routines for anything with nucleic acids in it because I had invented the Polymerase Chain Reaction. That's why they had hired me.

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), on the other hand, was something I did not know a lot about. Thus, when I found myself writing a report on our progress and goals for the project, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, I recognized that I did not know the scientific reference to support a statement I had just written: "HIV is the probable cause of AIDS."

So I turned to the virologist at the next desk, a reliable and competent fellow, and asked him for the reference. He said I didn't need one. I disagreed. While it's true that certain scientific discoveries or techniques are so well established that their sources are no longer referenced in the contemporary literature, that didn't seem to be the case with the HIV/AIDS connection. It was totally remarkable to me that the individual who had discovered the cause of a deadly and as-yet-uncured disease would not be continually referenced in the scientific papers until that disease was cured and forgotten. But as I would soon learn, the name of that individual - who would surely be Nobel material - was on the tip of no one's tongue.

Of course, this simple reference had to be out there somewhere. Otherwise tens of thousands of public servants and esteemed scientists of many callings, trying to solve the tragic deaths of a large number of homosexual and/or intravenous (IV) drug-using men between the ages of twenty-five and forty, would not have allowed their research to settle into one narrow channel of investigation. Everyone wouldn't fish in the same pond unless it was well established that all the other ponds were empty. There had to be a published paper, or perhaps several of them, which taken together indicated that HIV was the probable cause of AIDS. There just had to be.

I did computer searches, but came up with nothing. Of course, you can miss something important in computer searches by not putting in just the right key words. To be certain about a scientific issue, it's best to ask other scientists directly. That's one thing that scientific conferences in faraway places with nice beaches are for.

I was going to a lot of meetings and conferences as part of my job. I got in the habit of approaching anyone who gave a talk about AIDS and asking him or her what reference I should quote for that increasingly problematic statement, "HIV is the probable cause of AIDS."

After ten or fifteen meetings over a couple years, I was getting pretty upset when no one could cite the reference. I didn't like the ugly conclusion that was forming in my mind: The entire campaign against a disease increasingly regarded as a twentieth century Black Plague was based on a hypothesis whose origins no one could recall. That defied both scientific and common sense.

Finally, I had an opportunity to question one of the giants in HIV and AIDS research, Dr Luc Montagnier of the Pasteur Institute, when he gave a talk in San Diego. It would be the last time I would be able to ask my little question without showing anger, and I figured Montagnier would know the answer. So I asked him.

With a look of condescending puzzlement, Montagnier said, "Why don't you quote the report from the Centers for Disease Control? "

I replied, "It doesn't really address the issue of whether or not HIV is the probable cause of AIDS, does it?"

"No," he admitted, no doubt wondering when I would just go away. He looked for support to the little circle of people around him, but they were all awaiting a more definitive response, like I was.

"Why don't you quote the work on SIV [Simian Immunodeficiency Virus]?" the good doctor offered.

"I read that too, Dr Montagnier," I responded. "What happened to those monkeys didn't remind me of AIDS. Besides, that paper was just published only a couple of months ago. I'm looking for the original paper where somebody showed that HIV caused AIDS.

This time, Dr Montagnier's response was to walk quickly away to greet an acquaintance across the room.

Cut to the scene inside my car just a few years ago. I was driving from Mendocino to San Diego. Like everyone else by now, I knew a lot more about AIDS than I wanted to. But I still didn't know who had determined that it was caused by HIV. Getting sleepy as I came over the San Bernardino Mountains, I switched on the radio and tuned in a guy who was talking about AIDS. His name was Peter Duesberg, and he was a prominent virologist at Berkeley. I'd heard of him, but had never read his papers or heard him speak. But I listened, now wide awake, while he explained exactly why I was having so much trouble finding the references that linked HIV to AIDS. There weren't any. No one had ever proved that HIV causes AIDS. When I got home, I invited Duesberg down to San Diego to present his ideas to a meeting of the American Association for Chemistry. Mostly skeptical at first, the audience stayed for the lecture, and then an hour of questions, and then stayed talking to each other until requested to clear the room. Everyone left with more questions than they had brought.

I like and respect Peter Duesberg. I don't think he knows necessarily what causes AIDS; we have disagreements about that. But we're both certain about what doesn't cause AIDS.

We have not been able to discover any good reasons why most of the people on earth believe that AIDS is a disease caused by a virus called HIV. There is simply no scientific evidence demonstrating that this is true.

We have also not been able to discover why doctors prescribe a toxic drug called AZT (Zidovudine) to people who have no other complaint than the presence of antibodies to HIV in their blood. In fact, we cannot understand why humans would take that drug for any reason.

We cannot understand how all this madness came about, and having both lived in Berkeley, we've seen some strange things indeed. We know that to err is human, but the HIV/AIDS hypothesis is one hell of a mistake.

I say this rather strongly as a warning. Duesberg has been saying it for a long time.”

Mullis’s words deeply resonated with me, particularly his approach to uncovering the truth. Kary wasn’t a virologist or an “expert” in the HIV/AIDS narrative, but that didn’t deter him from investigating and going straight to the source. Using simple logic, Mullis meticulously searched for the foundational evidence supporting the HIV/AIDS hypothesis—even confronting Montagnier directly. Yet, he discovered that no one could provide the necessary scientific evidence to substantiate the hypothesis.

“I think it's simple logic. It doesn't require that anyone have any specialized knowledge of the field. The fact is that if there were evidence that HIV causes AIDS-if anyone who was in fact a specialist in that area could write a review of the literature, in which a number of scientific studies were cited that either singly or as a group could support the hypothesis that HIV is the probable cause of AIDS-somebody would have written it. There's no paper, nor is there a review mentioning a number of papers that all taken together would support that statement.”

https://www.virusmyth.com/aids/hiv/ramullis.htm

The above quote from Mullis, taken from a 1994 Rethinking AIDS interview, had such a profound impact on me that I included it on the opening page of ViroLIEgy.com. It continues to serve as a guiding light in how I approach my own research to this day. Needless to say, Kary Mullis was instrumental in my awakening, and I’ve shared his words with many in the hope that they, too, might find value in his insights.

As “Covid” hysteria spread worldwide and PCR testing became central to the so-called “pandemic,” Kary Mullis naturally emerged as a pivotal figure in the information war. His warnings against using PCR solely as a diagnostic tool resurfaced, with memes and messages challenging the mainstream narrative. Mullis’s skepticism of the HIV/AIDS hypothesis and his outspoken criticisms of Anthony Fauci—a key figure in both “crises”—became rallying cries for those questioning the official story. Many saw him as a hero who would have exposed the misuse of his invention to fuel panic over an unproven hypothesis. His sudden and suspiciously-timed death in August 2019, just months before the “pandemic,” further elevated his legacy as a rebellious voice silenced by the pharmaceutical cartel.

While many see Mullis as an unsung hero, others view him as a hidden villain designed to obscure the truth. Frustrated by the rise of Mullis as a martyr, these individuals seek to reframe him as a menace. They point to his unwavering belief in PCR, his acceptance of “viruses” and “antibodies,” his ties to the pharmaceutical industry, and his Nobel Prize win as reasons to discredit him. Critics have gone to great lengths to dismiss and smear him as a gatekeeper blocking access to the real truth, penning lengthy essays that lean on dubious connections to sow doubt and distrust. Perhaps the central argument from these individuals is that Mullis’s words have been misinterpreted, asserting that he actually supported using PCR as a sole diagnostic tool for “infectious” disease rather than opposing it, making him the monster responsible for current and future “pandemics.”

Two competing narratives surround Mullis—his role as a seeker of truth and his beliefs about the use of his invention. Whether he is the hero some revere or the villain others portray may always be open to interpretation. However, we can address what appears to be the central question that has fueled doubts about him: Did Kary Mullis truly believe PCR could be used as the sole method to diagnose “infectious” disease, as it was during the “Covid crisis?” Is he responsible for the misuse of his invention as a diagnostic tool to fabricate cases in order to declare “pandemics?” And will clarifying his views help resolve the confusion about him and sway opinions one way or the other? Let’s find out.

The debate over whether Kary Mullis supported the use of PCR as a diagnostic test for “infectious” disease centers on three main pieces of evidence: his 1985 PCR patent and a paper on PCR attributed to him, a section from his 1998 book, and an email from a 2007 HIV judicial case. As Mullis might suggest, to thoroughly examine these pieces of evidence and the questions they raise, it’s important to return to the foundational source. In this case, that means considering Mullis’s own statements about his invention and its intended purpose. The widely accepted narrative of PCR’s invention is that Mullis had a “Eureka!” moment in April 1983 while driving, which led him to develop a process for making unlimited copies of DNA fragments. Mullis reflected on this breakthrough and his excitement over PCR’s potential in a 1990 paper, where he emphasized its remarkable ability to amplify DNA from virtually any source—whether ancient samples, forensic evidence, or complex biological mixtures. He described the process as relatively simple, suitable for both pure DNA samples and those containing various biological components.

The Unusual Origin of the Polymerase Chain Reaction

A surprisingly simple method for making unlimited copies of DNA fragments was conceived under unlikely circumstances-during a moonlit drive through the mountains of California

“Sometimes a good idea comes to you when you are not looking for it. Through an improbable combination of coincidences, naivete and lucky mistakes, such a revelation came to me one Friday night in April, 1983, as I gripped the steering wheel of my car and snaked along a moonlit mountain road into northern California's redwood country. That was how I stumbled across a process that could make unlimited numbers of copies of genes, a process now known as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Beginning with a single molecule of the genetic material DNA, the PCR can generate 100 billion similar molecules in an afternoon. The reaction is easy to execute: it requires no more than a test tube, a few simple reagents and a source of heat. The DNA sample that one wishes to copy can be pure, or it can be a minute part of an extremely complex mixture of biological materials. The DNA may come from a hospital tissue specimen, from a single human hair, from a drop of dried blood at the scene of a crime, from the tissues of a mummified brain or from a 40,000-year-old woolly mammoth frozen in a glacier.”

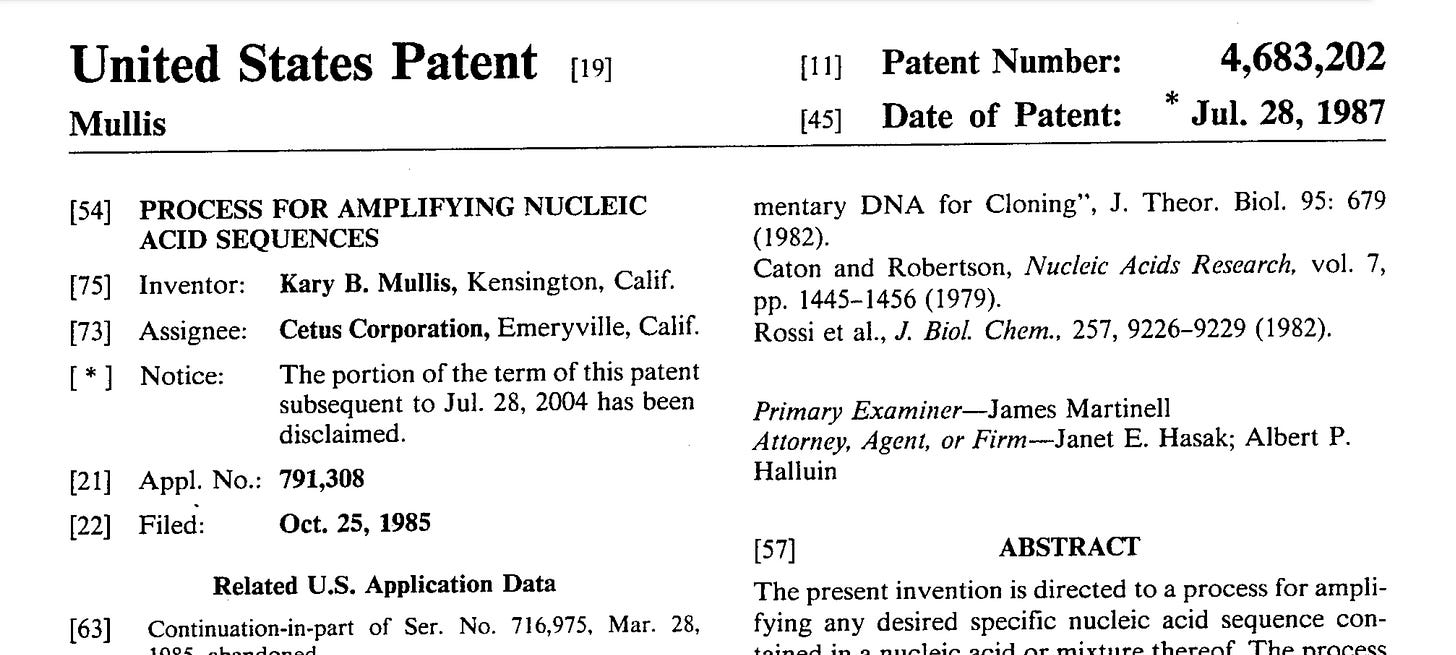

The 1985 Patent

In 1985, Kary Mullis patented his invention, describing it as a “process for amplifying any desired specific nucleic acid sequence contained in a nucleic acid or mixture thereof.” Its potential applications were outlined, emphasizing PCR’s ability to detect and characterize specific nucleic acid sequences associated with “infectious” diseases, genetic disorders, or cellular abnormalities like cancer. As an example, the prenatal diagnosis of sickle cell anemia, a genetic condition, was highlighted. The patent also discussed the potential for diagnosing “infectious” diseases, stating: “Various infectious diseases can be diagnosed by the presence in clinical samples of specific DNA sequences characteristic of the causative microorganism.”

A prior patent by Stanley Falkow was referenced, which described using DNA hybridization probes for diagnosing “infectious” diseases, and it was proposed how to improve upon this method’s sensitivity and specificity through the specific amplification of suspected DNA sequences before detection. The patent also pointed to a process detailed by Ward in European Patent 63,879, which PCR could be used to enhance the clinical utility of DNA probes by incorporating non-radioactively labeled probes, simplifying routine diagnostics for “infectious” diseases.

These were suggestions for untested theoretical applications that could make existing procedures, such as those by Falkow and Ward, more practical in routine clinical settings. At the time the patent was written, PCR was envisioned as being used to detect “infectious” diseases, pathological abnormalities, and non-pathological DNA polymorphisms in organisms’ genomes. Specifically, the anticipation was that PCR could help identify, in patient DNA samples, sequences associated with “infectious” diseases.

“The method herein may also be used to enable detection and/or characterization of specific nucleic acid sequences associated with infectious diseases, genetic disorders or cellular disorders such as cancer. Amplification is useful when the amount of nucleic acid available for analysis is very small, as, for example, in the prenatal diagnosis of sickle cell anemia using DNA obtained from fetal cells. Amplification is particularly useful if such an analysis is to be done on a small sample using non-radioactive detection techniques which may be inherently insensitive, or where radioactive techniques are being employed but where rapid detection is desirable.”

“Various infectious diseases can be diagnosed by the presence in clinical samples of specific DNA sequences characteristic of the causative microorganism. These include bacteria, such as Salmonella, Chlamydia, and Neisseria; viruses, such as the hepatitis viruses; and protozoan parasites, such as the Plasmodium responsible for malaria. U.S. Pat. No. 4,358,535 issued to Falkow describes the use of specific DNA hybridization probes for the diagnosis of infectious diseases. A problem inherent in the Falkow procedure is that a relatively small number of pathogenic organisms may be present in a clinical sample from an infected patient and the DNA extracted from these may constitute only a very small fraction of the total DNA in the sample. Specific amplification of suspected sequences prior to immobilization and hybridization detection of the DNA samples could greatly improve the sensitivity and specificity of these procedures.

Routine clinical use of DNA probes for the diagnosis of infectious diseases would be simplified considerably if non-radioactively labeled probes could be employed as described in EP 63,879 to Ward. In this procedure biotin-containing DNA probes are detected by chromogenic enzymes linked to avidin or biotin-specific antibodies. This type of detection is convenient, but relatively insensitive. The combination of specific DNA amplification by the present method and the use of stably labeled probes could provide the convenience and sensitivity required to make the Falkow and Ward procedures useful in a routine clinical setting.

The amplification process can also be utilized to produce sufficient quantities of DNA from a single copy human gene such that detection by a simple non-specific DNA stain such as ethidium bromide can be employed so as to make a DNA diagnosis directly.

In addition to detecting infectious diseases and pathological abnormalities in the genome of organisms, the process herein can also be used to detect DNA polymorphism which may not be associated with any pathological state.”

“The present process is expected to be useful in detecting, in a patient DNA sample, a specific sequence associated with an infectious disease such as, e.g., Chlamydia using a biotinylated hybridization probe spanning the desired amplified sequence and using the process described in U.S. Pat. No. 4,358,535, supra.”

The language in Kary Mullis's 1985 patent does suggest that his invention could be used to detect sequences related to “pathogenic” entities in order to diagnose “infectious” diseases. This has been a cornerstone argument for those who claim that Mullis was not opposed to the use of PCR for diagnosing such diseases. However, this argument reveals a misunderstanding of the patent process and disregards Mullis’s later statements on the subject.

At the time of the patent's filing in 1985, PCR was considered a groundbreaking innovation with immense potential. Many of the applications described in the patent, including diagnostic uses for “infectious” diseases, were speculative and had not been fully realized or validated. The patent’s primary focus was on detailing the PCR process itself, with examples like “infectious” disease detection included to illustrate the broad potential scope of the technology.

In a 2005 interview, Mullis explained that, at that time, he was trying to think of all possible uses for his invention, but that his primary focus was on one area: looking for genetic diseases, particularly defects in fetal material or in people who were already grown up but needed a definitive diagnosis.

“At the time, it was very early on. I was just thinking of it as a way of testing, because the amount of genetic testing going on at that time, in 1983, would have been manageable, in terms of send it by FedEx to some company, and we’ll send you back the answer the next day. The idea that PCR was going to be used in every DNA laboratory in the world, in the way it is now, for all kinds of things, hadn’t really set in to me. I figured it was going to spread. I kept thinking of things it would be useful for, but mostly just for that one, looking for genetic diseases, particularly defects in fetal material or in people who were already grown up but needed a definitive diagnosis. I was thinking of it more of that way. The number of people undergoing these procedures back then was very, very small.”

He went on to explain how patents work, highlighting the distinction between his patent, US4683202A, which described the invention itself, and another patent, US4683195A, filed by Cetus, the organization he worked for at the time, which outlined numerous theoretical applications for the technology. Both patents contained identical language in sections related to the use of PCR for “infectious” disease diagnosis.

Since patents are a collaborative effort involving corporate patent attorneys, technical writers, and scientists within the company, it is doubtful Mullis even wrote the sections discussing PCR’s potential application to “infectious” disease diagnosis. In fact, further reinforcing this doubt, Making PCR: A Story of Biotechnology (1996) by Paul Rabinow notes that Cetus initially saw PCR’s commercial potential in diagnostic tests, with Tom White and Jeff Price playing key roles in developing PCR methods for “infectious” disease diagnostics. Henry Erlich, leader of the human genetics team listed on the “applications” patent alongside Kary Mullis, was focused on the company's demand for commercial products such as diagnostic and forensic tests.

Tom White recognized the potential in Mullis’ idea and tasked Erlich and his human genetics team—including Randy Saiki, Steve Scharf, and Norm Arnheim—with working in parallel with Mullis. The language in the patents focused on “infectious” disease diagnostics closely mirrors that of a 1985 paper by Saiki, Arnheim, and Erlich, which will be discussed further later. It is very likely that these men were the ones who included the material relating to PCR and “infectious” disease in the patent.

Mullis further explained that he did not concern himself with the listed uses, as his name was automatically included on all related patents. This strategy allowed Cetus to claim a broad range of potential applications for PCR, primarily to protect the company from others attempting to patent specific uses of the invention.

“To people who don’t understand how things work at the patent office, because it has a lower number, it looks like it had been applied for earlier. If you read the patent carefully you saw that one of them was really the invention and the other one was the uses of it. Then there were just probably 100 patents on the various uses of PCR and so forth, which I didn’t care about. My name is always on those anyway, because it allowed Cetus to claim a whole lot of uses of PCR that really looked kind of obvious. They still had my name on it. It’s an element of patent law that if you invent something new you can patent all kinds of applications of it that are not really novel. They’re only novel when they’re used in conjunction with this new thing, like taking a piece of DNA that you have copied using PCR and doing various things that are known already in the art that you can do with DNA, which is not itself really an invention. If you’re the inventor of the original thing that is considered an invention, then you can patent all those things.

The reason the patent office does that is to prevent somebody else later on from using your invention and patenting some application of it that really itself is not an invention. Because of a different patent examiner looking at it and changing it, he doesn’t see it. He gives them a patent on some use of your invention, which is really not novel. Then you end up having to pay money to somebody to use your invention in that way, and it’s not considered fair. Any other invention that you try to patent using your invention, they just give it to you, but they put a little thing on there that says that whenever the original patent is no longer valid, this patent is longer valid, its time runs out. It’s called a terminal disclaimer. You can see that on a lot of the later patents on the PCR line. They'll say this is granted under a terminal disclaimer regarding patent number such and such.”

https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/items/43ae071a-2a9a-4670-b600-7c20666f9df8

In a 1994 paper, Kary Mullis reflected on the process of writing a patent, describing it as an exercise in presenting an invention as transformative, with the potential to enable future possibilities, without necessarily having to prove them. He admitted to leaving the drafting of the claims—what he called the “meat of the patent”—to his colleague Janet, as he was unaware of their critical importance. Mullis emphasized that the claims determine ownership of the invention, cautioning that anything not explicitly included would not be legally protected.

Looking back, Mullis acknowledged that neither he nor Janet had a thorough understanding of patent litigation, which left their claims vulnerable to challenges. Despite this, his goal was to craft broad claims that would avoid being shortsighted, while expressing the invention’s essence with clarity and brevity. This approach, though academically appealing, lacked the strategic redundancy necessary to withstand legal scrutiny.

PCR and Scientific Invention: The Trial of DuPont vs. Cetus

“A patent claim, besides being a single, long, run-on sentence with which your worst English teacher in high school would have been unamused, and your best English teacher would have been intrigued on account of your cleverness for contriving its intricacies, is a mechanism by which you describe what you have invented and distinguish it from what may have been done similarly in the past, with the ultimate goal of claiming that you have done something that makes almost everything possible and that is exemplary of anything useful someone might want to do in the future and yet is not exemplary of anything that has been done in the past, most of which simply pointed out the need for your invention without showing the way to it.

When Janet and I were writing the application for what became US 4,683,202, Janet told me at first to leave the claims mainly to her, which suited me fine, as I was ignorant of the central importance of claims and had never appreciated their puzzling elegance. I had no idea I would someday be testifying as to their appropriateness in a federal court and that on their validity would hang a serious fraction of a billion dollars. We worked pretty well together though and as time passed so did the division of labor. The claims were as much my fault as hers.

A claim is the meat of a patent. If it is not in the claims, then you do not own it in the end, and if it is in a claim and somebody can prove to the patent office or a court that anything in your claim has already been done somewhere else in the past and published, then your patent can be invalidated.

The patent office and the federal courts arise from independent branches of government. The executive branch patent and trademark lawyers, in keeping with the general irrational nature of civilization as augmented by Thomas Jefferson et al., are constitutionally subordinate even in matters requiring their specialized skills to the plain old general practitioner type of lawyers and judges who hang around federal courts and are more skilled in the arts of murder and rape than in chemistry. It is the judicial branch, these guys, that finally decides.

Disregarding this technicality, it is fair that if something's already in the public domain, a pretender to its invention should not be allowed to have a monopoly on its use just because of greed or a misunderstanding.

If someone explained patent litigation to me while Janet and I were drafting our claims, I certainly was not paying attention. Our claims were not baroque enough to deal brusquely, when the time came, with the infidels from Wilmington.

We had a breakthrough, a pioneering invention, and we wanted broad claims that would not appear shortsighted when derivative technologies started to appear. But I did not want them to wander all over the place or diverge into triple counterpoint. I wanted them to say what they had to say in the least number of words, and get out of there. Janet was not a debater in high school, would not stoop to vitriol when logic failed, and could not type as fast as I. She is an agreeable person and friendly. As we batted sections of the draft back and forth on the computer, I prevailed in bringing a sense of my own esthetics into the document, and in my desire that the wording be lean, I naively left the patent open to attack. In a lean, logical way we covered everything, but without the benefit of comfortable near-redundant fall back positions. I'd never been in litigation. I was playing without a full deck, emulating an academic publication. Janet sensed what it might be like to have a patent challenged, but couldn't bring herself to expose me to the fact that her colleagues were not lean and logical, in fact, with exceptions, they were fat and illogical, and somebody else was always paying for the paper, and the writing on it, and the later reading of it, by the hour.”

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4612-0257-8_35

Mullis acknowledged that the claims in the PCR patent were designed to cover not only the known uses of the invention but also potential future applications. He noted, however, that some of these claims may have been overly ambitious or not entirely grounded in practical reality at the time, which could have left the patent vulnerable to legal challenges later.

This highlights an often-misunderstood aspect of the patent process: inventors are not required to fully prove their invention works or explain every detail of how it functions. In other words, not all the claims are based on actual data, and they can be hypothetical predictions. Inventors are allowed to include what are known as prophetic examples, which are predicted experimental methods and results that are written in the present or future tense. These are hypothetical uses or applications of an invention that have not yet been experimentally verified at the time the patent is filed. The essential requirement is to disclose enough information so that someone skilled in the relevant field can understand the invention and assess the scope of the claims.

“Although it may surprise scientists, one can receive a patent in many jurisdictions without implementing an invention in practice and demonstrating that it works as expected. Instead, inventors applying for patents are allowed to include predicted experimental methods and results, known as prophetic examples, as long as the examples are not written in the past tense (1–3). Allowing untested inventions to be patented may encourage earlier disclosures about new ideas and provide earlier certainty regarding legal rights—which may help small firms acquire financing to bring their ideas to market.”

“A patent application need only contain sufficient information that a skilled researcher in the field would recognize as credibly demonstrating how to make and use the invention (6). Prophetic examples are one way to help satisfy this legal standard for inventions that have not yet been demonstrated to work (2). Although prophetic examples that are close variations on actual experiments are preferable, many prophetic examples appear to be entirely hypothetical predictions. Preliminary research suggests that these examples are particularly prevalent in chemistry and biology; an estimated 17% of examples in U.S. patents in these fields are prophetic, and almost one-quarter of U.S. patents in these fields have at least one prophetic example—making prophetic examples a commonplace feature (for examples, see the box) (7).”

Patent claims need only to appear logical and plausible to the reviewer for approval. Once approved, those claims are legally protected, even if they are never realized in practice or if the invention is used in ways not initially envisioned. Ultimately, the goal of patent drafting is to cover all conceivable applications to prevent others from patenting derivative uses and claiming ownership.

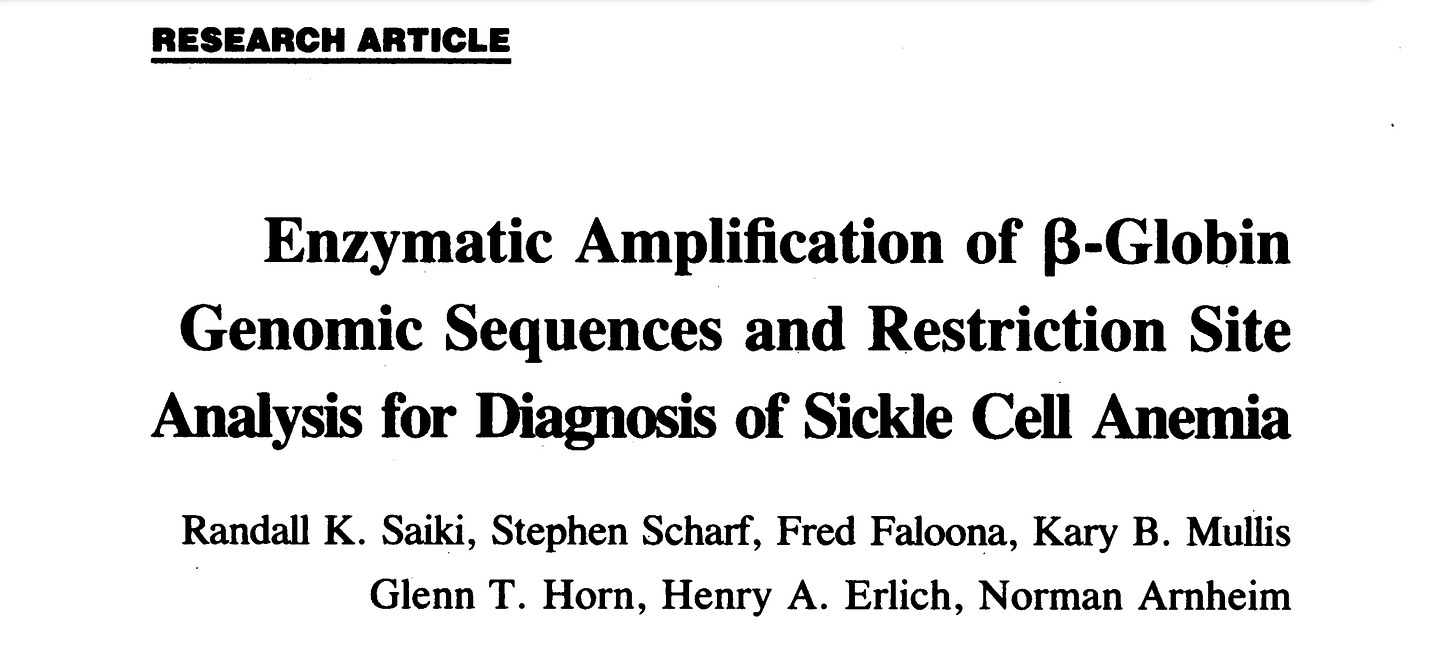

The 1985 Paper(s)

Using Mullis's 1985 PCR patent as evidence that he believed his invention should be used to diagnose “infectious” diseases is misleading and contradicts his actual vision, which was for diagnosing genetic diseases. Possibly realizing this, along with misrepresenting the patent, detractors of Mullis often cite another 1985 paper to support the claim that Mullis favored PCR as a diagnostic tool for “infectious” diseases. This is based on a line within the paper stating that PCR could be generally applicable to diagnosing genetic diseases other than sickle cell anemia, as well as in the use of DNA probes for diagnosing “infectious” diseases.

Enzymatic Amplification of B-Globin Genomic Sequences and Restriction Site Analysis for Diagnosis of Sickle Cell Anemia

“We have developed a procedure for the detection of the sickle cell mutation that is very rapid and is at least two orders of magnitude more sensitive than standard Southern blotting. There are two special features to this protocol. The first is a method for amplifying specific B-globin DNA sequences with the use of oligonucleotide primers and DNA polymerase (12). The second is the analysis of the B-globin genotype by solution hybridization of the amplified DNA with a specific oligonucleotide probe and subsequent digestion with a restriction endonuclease (13). These two techniques increase the speed and sensitivity, and lessen the complexity of prenatal diagnosis for sickle cell anemia; they may also be generally applicable to the diagnosis of other genetic diseases and in the use of DNA probes for infectious disease diagnosis.”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2999980/

However, Randall Saiki was the lead author of this paper, with Kary Mullis listed as one of several co-authors. Mullis was apparently involved in name only and never saw the final draft until it was printed. According to Rabinow, two papers were being worked on simultaneously. Mullis was writing a “fundamentals” paper detailing the PCR method, which was intended to be published first, while Saiki and his team were working on the “applications” paper, which would follow.

Tom White had given Mullis a firm deadline of November 1, 1985, to complete the “fundamentals” paper, after which Cetus would submit the “applications” paper for publication. However, since Saiki had already presented PCR at a conference in October, Cetus was under pressure to establish priority in the literature for commercial and patent purposes. When Mullis failed to complete his paper on time, Cetus proceeded with publishing Saiki's paper first.

Mullis later recounted how angered he was by the paper and how he felt betrayed by his company.

“The paper [Saiki RK, Scharf S, Faloona F, Mullis KB, Horn GT, Erlich HA, Arnheim N. Enzymatic amplification of beta-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science. 1985 Dec 20;230(4732):1350-4] went through many different editings, under the influence, I think, of the editor of Science, who obviously thought, “Hey, you can’t publish data that you don‟t explain how you got.” They ended up explaining exactly how to do PCR, and I never ended up seeing that edition, that editing of the paper that, instead of just saying, using the method of Mullis and Faloona, actually explained how they did it. I didn’t see that until it was in the goddamn magazine, so that pissed me off.

That happened around Christmas in 1985. I felt totally betrayed by them doing that. When the whole story had to be told in truth to lawyers under oath, when Du Pont sued Cetus to try to overturn the patents, in that case, they finally had to buck up to the fact that they had actually screwed me over on that.”

Mullis’ “fundamentals” paper, co-authored with his lab technician Fred Faloona, described his invention in detail. Initially, he submitted it to Nature and Science, two of the most prestigious scientific journals, but both rejected it, citing a lack of novelty and referencing the “applications” paper submitted by his co-workers.

It was not until 1987 that Mullis finally succeeded in publishing his work, which appeared in Methods in Enzymology Volume 155. In this paper, he outlined his method for exponentially amplifying a nucleic acid sequence in vitro and discussed what he saw as its potential applications, which included DNA diagnostics and molecular cloning.

Specific Synthesis of DNA in Vitro via a Polymerase-Catalyzed Chain Reaction

“We have devised a method whereby a nucleic acid sequence can be exponentially amplified in vitro. The same method can be used to alter the amplified sequence or to append new sequence information to it. It is necessary that the ends of the sequence be known in sufficient detail that oligonucleotides can be synthesized which will hybridize to them, and that a small amount of the sequence be available to initiate the reaction.”

“The polymerase chain reaction has thus found immediate use in developmental DNA diagnostic procedures and in molecular cloning from genomic DNA; it should be useful wherever increased amounts and relative purification of a particular nucleic acid sequence would be advantageous, or when alterations or additions to the ends of a sequence are required.”

This excerpt from Mullis reflects his early perspective on the intended uses of PCR, emphasizing its value in specific, well-defined applications such as developmental DNA diagnostics, molecular cloning, and sequence-specific amplification. His focus on achieving “increased amounts and relative purification of a particular nucleic acid sequence” highlights that PCR was designed as a tool to amplify specific genetic sequences, not as a standalone diagnostic test. Mullis’s insights align with his broader view of PCR as a tool for studying and manipulating genetic material, rather than for diagnosing “infectious” diseases.

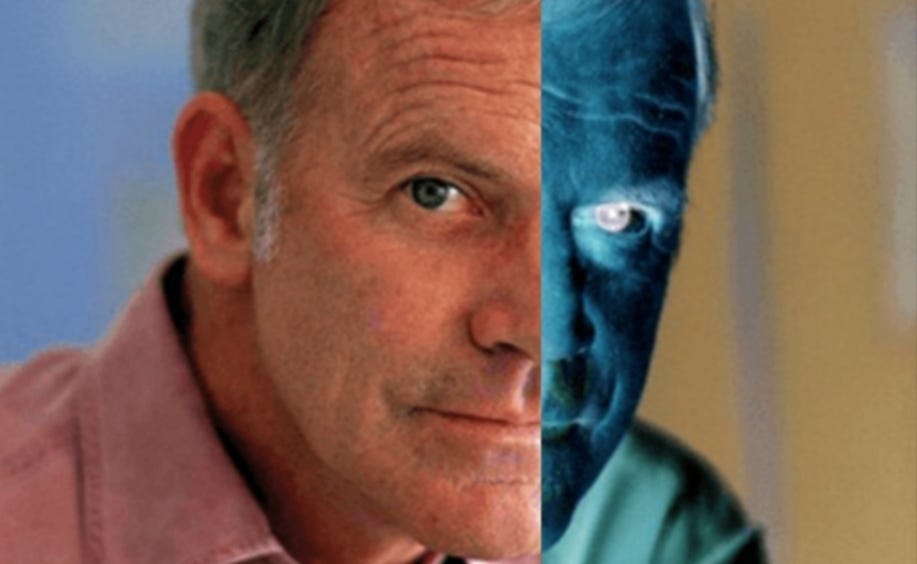

The 1997 Interview

Thus, the 1985 patent and paper are not “smoking guns” proving that Kary Mullis intended for his invention to be used as a diagnostic tool for “infectious” diseases. However, to eliminate any lingering doubts about his stance, Mullis directly addressed the issue twelve years later during a question-and-answer session in Santa Monica on July 12, 1997. When asked about the misuse of PCR, Mullis explained that its ability to amplify tiny amounts of genetic material could lead to misleading conclusions. He emphasized that PCR can detect fragments of almost anything in anyone, making it difficult to determine whether the detected material is significant or harmful. Mullis stated that results are often overinterpreted, assigning undue meaning to the presence of amplified molecules. While he acknowledged PCR's strength in producing measurable quantities, he clarified that it does not indicate illness, harm, or causation. Instead, it relies on inferences from invisible components, undermining its diagnostic value and rendering many results meaningless.

I don’t think you can “misuse” PCR—the results, the interpretation of it—see, if…they could find this virus in you at all, and PCR, if you do it well, you can find almost anything in anybody, it starts making you believe in the sort of Buddhist notion that everything is contained in everything else…if you can amplify one single molecule up to something you can really measure, which PCR can do, then there are very few molecules that you don’t have at least one single one of them in your body. That is how it can be thought of as misuse of it—to claim that it is meaningful.

The real misuse of it is, you don’t need to test for HIV, you don’t need to test for the other 10,000 other retroviruses that are unnamed…it allows you to take a minuscule amount of anything and make it measurable and then talk about its meaning as if it is important—that’s not a misuse that is a sort of misinterpretation…the measurement for it is not exact at all. It’s not as good as our measurement for things like apples. An apple is an apple. If you get enough things that look kind of like an apple and you stick them all together, you might think of it as an apple. Those tests are all based on things that are invisible and the results are inferred…

It’s a process that’s used to make a whole lot of something out of something…it doesn’t tell you that you’re sick and it doesn’t tell you that the thing you ended up with really was going to hurt you or anything like that.”

Despite Mullis's clear and unequivocal remarks discrediting the use of PCR as a diagnostic tool for “infectious” diseases, some have attempted to dismiss his comments as “edited” or taken out of context. For those interested in hearing Mullis's unedited response in its entirety, please refer to the videos linked below.

Corporate Greed and AIDS Part 1 (Mullis starts speaking at around the 1 hour and 29 minute mark)

Corporate Greed and AIDS Part 2 (Mullis answers the PCR question at about the 48 minute and 50 second mark)

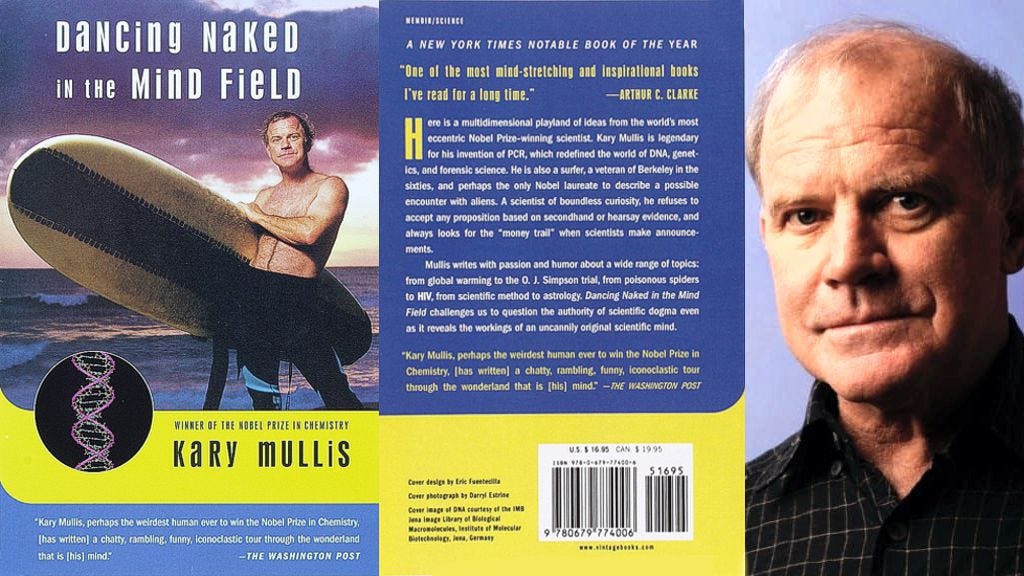

The 1998 Book

Interestingly, some have argued that Mullis later contradicted himself on page 105 of his 1998 book Dancing in the Mind Field. The highlighted section discussed PCRs value in diagnosing genetic diseases while also being used to detect genes from so-called “infectious pathogens” that are difficult or impossible to culture.

“The procedure would be valuable in diagnosing genetic diseases by looking into a person’s genes. It would find infectious diseases by detecting the genes of pathogens that were difficult or impossible to culture. PCR would solve murders from DNA samples in trace materials—semen, blood, hair. The field of molecular paleobiology would blossom because of PCR. Its practitioners would inquire into the specifics of evolution from the DNA in ancient specimens. The branchings and migrations of early man would be revealed from fossil DNA and its descendant DNA in modern humans. And when DNA was finally found on other planets, it would be PCR that would tell us whether we had been there before or whether life on other planets was unrelated to us and had its own separate roots.”

However, while Kary Mullis acknowledged PCR's utility in detecting the genetic material of “pathogens” that are difficult to culture, he did not imply that PCR alone is sufficient to diagnose an “infectious” disease. Instead, the passage highlights PCR's role in identifying genetic material, which would support research and investigations but does not address critical clinical interpretation issues. These would include distinguishing “active infections” from “harmless genetic fragments” or contamination. Therefore, it is not a contradiction as it aligns with Mullis's previous views, and this passage should not be misconstrued as Mullis advocating for PCR as a standalone diagnostic tool for “infectious” diseases. Rather, it emphasized his belief in it as a valuable component within broader scientific and investigative contexts.

The 2007 Paranzee Case

Mullis recent portrayal as a villain who supported the use of his invention, PCR, as a diagnostic test for “infectious” diseases hinges on one final piece of evidence often cited as the definitive blow to his credibility. In 2007, Mullis became indirectly involved in the South Australian case of Andre Chad Parenzee, a man sentenced to nine years in prison in 2007 on three counts of “endangering life” after one of his alleged victims, a mother of two, was diagnosed with HIV. The defense, heavily influenced by Eleni Papadopulos-Eleopulos and the Perth Group, argued that HIV does not exist. As part of her testimony, Papadopulos-Eleopulos claimed that Mullis had expressed doubts about the reliability of PCR, a statement noted in Judge Sulan's final ruling.

“Ms Papadopulos-Eleopulos had said that the inventor of PCR was purported to have expressed a lack of confidence in PCR. Professor Mullis received a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for having invented the PCR technique. As a consequence of the reference to Professor Mullis, Professor McDonald made contact with him.”

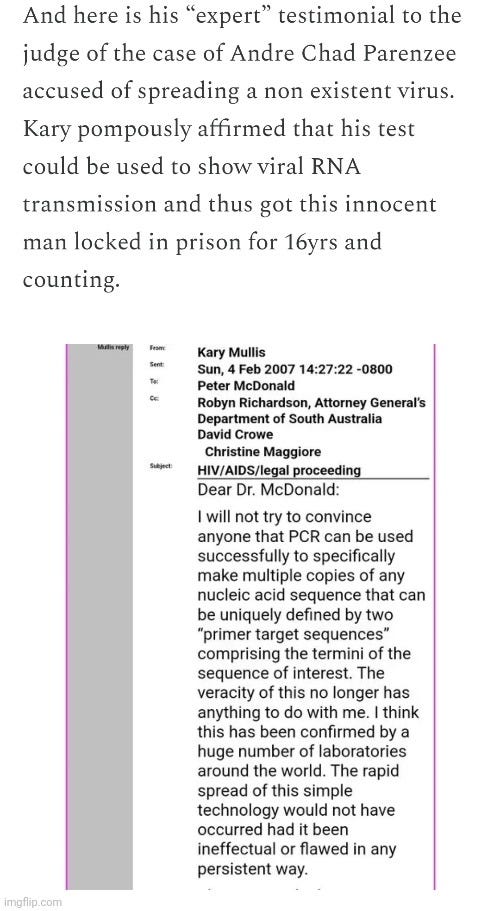

One of the prosecution's witnesses, Professor Peter James McDonald, contacted Kary Mullis after Eleni Papadopulos-Eleopulos referenced him during the case. A cropped portion of Mullis’s response to McDonald has since been misrepresented to suggest that Mullis “pompously affirmed that his test could be used to demonstrate viral RNA transmission.” It is further claimed that this alleged affirmation played a key role in Parenzee’s conviction.

However, does the cropped portion of Mullis's response truly convey what his detractors claim it does? And, more importantly, did it play a decisive role in Parenzee's conviction? To answer these questions, let’s examine the full email exchange and see if the matter can be clarified. This is what Professor McDonald wrote to Kary Mullis on February 3rd, 2007:

I am assisting the prosecution in an Appeal to the Supreme court in South Australia about a conviction for criminal transmission of HIV. The basis for that Appeal is that HIV does not exist and that the PCR technology is flawed. So in effect the technical basis for identification of virus is on trial.

The group of denialists giving evidence are people from Perth [Eliopolous-Papdopolous and Turner] who quote you as indicating that PCR technology is erroneous and misleading.

Can I ask you to comment on this statement. The Supreme Court Trial will continue for another few days and I would appreciate your comment as a matter of urgency.

I look forward to your response

Peter McDonald

Emeritus Professor

Kary Mullis responded a day later on February 4th, 2007:

Dear Dr. McDonald:

I will not try to convince anyone that PCR can be used successfully to specifically make multiple copies of any nucleic acid sequence that can be uniquely defined by two “primer target sequences” comprising the termini of the sequence of interest. The veracity of this no longer has anything to do with me. I think this has been confirmed by a huge number of laboratories around the world. The rapid spread of this simple technology would not have occurred had it been ineffectual or flawed in any persistent way.

The matter which you are considering, if I understand it correctly, is that the presence or absence of a given nucleic acid sequence, as determined by PCR, can be used as a reliable marker for a living organism in a biological sample. This is done quite often in scientific studies, but that does not mean there could never be exceptions. Remember scientific studies are done with the understanding that findings will be subject to scrutiny from colleagues. A nucleic acid segment very similar in size and terminal base could easily, in a cursory examination, be mistaken for the sequence in question. If this happened in the course of a normal scientific finding, somebody would finally notice it. Papers are retracted all the time. I am not aware of the nature of the evidence you are considering, but when it comes to legal issues, retractions don’t necessarily make up for the original mistake, and if I were to offer advice to the courts system of Australia, I would plead that they realize that the AIDS/HIV issue is what is not settled scientifically, not the effectiveness of PCR.

I have enclosed a paper I published some years ago which encapsulates my personal opinion concerning the cause of AIDS. I represent a very small minority among scientists who have seriously considered this matter. Many scientific issues which are controversial are often decided in favor of the minority, by experiments. Some of the time the majority gets it right.

Prosecuting people based on an unproven hypothesis would seem to be unfair and rash. To cloak the real issues in a veneer of irrelevant technological detail is, in my opinion, a bit of a sham, unworthy of Australians.

Sincerely yours,

Dr. Kary B. Mullis

Professor McDonald followed up with a response on February 17th, 2007, stating that Mullis had helped to confirm his view that PCR was a valid technology and that the quote of him “having no confidence in the technology” was inaccurate.

Many thanks for taking the time to respond to my request.

Your views were helpful in terms of confirming the validity of PCR in which you were being quoted as “having no confidence in the technology”.

Overall I think I share with you some scepticism about the jump from scientific observation to a deduction that HIV transmission and pathogenesis is set in stone and becomes a legitimate basis for criminal prosecution.

I personally do not believe that it is appropriate to lock people in jail for sexual transmission of HIV – but that is the law!

I thank you for your assistance and would be happy to keep a dialogue.

Kindest regards from down under

Peter

As seen from this exchange, Mullis was informed by Professor McDonald that the defense had claimed PCR technology was flawed and that the Perth Group had quoted him as saying that PCR was “erroneous and misleading.” In response, Mullis naturally defended his invention, stating that PCR can be used to “specifically make multiple copies of any nucleic acid sequence that can be uniquely defined by two ‘primer target sequences’ comprising the termini of the sequence of interest.” In doing so, Mullis affirmed his belief that PCR is a powerful tool for amplifying specific nucleic acid sequences—not as a diagnostic test.

Mullis also clarified that while PCR can detect the presence or absence of specific nucleic acid sequences, this does not automatically equate to identifying a living organism in a biological sample. He cautioned that false positives or misinterpretations could occur, especially if similar sequences were mistakenly amplified. This highlighted the importance of careful interpretation of PCR results, particularly in high-stakes applications such as medical diagnoses or legal proceedings.

Further, Mullis reiterated his personal skepticism about the mainstream hypothesis linking HIV to AIDS. He emphasized that the HIV/AIDS debate was scientifically unsettled, suggesting that the causal relationship between HIV and AIDS was not universally accepted among scientists. His comments reflected a broader concern about the validity of using HIV as a definitive marker for disease, particularly in legal contexts.

Mullis also expressed unease about prosecuting individuals based on what he deemed an “unproven hypothesis.” He warned against relying on PCR results as definitive evidence in legal cases involving HIV transmission, particularly given the unresolved scientific questions surrounding HIV and AIDS causation.

In the court’s final decision, Judge Sulan addressed this exchange. He noted that Professor McDonald interpreted Mullis’s response as expressing confidence in the PCR system, emphasizing that the debate was “not a controversy around whether PCR is a valid technology or technique.” McDonald also highlighted Mullis's 1995 paper, which discussed the ongoing controversy over the HIV/AIDS hypothesis. While the defense attorney, Kevin Borick, cited Mullis’s paper and other evidence of a continuing scientific debate, the judge dismissed it. He characterized Mullis’s views as an older, unsupported theory and argued that Mullis, despite his stature, was “not working or researching specifically in the area of HIV/AIDS.” Thus, the judge concluded that Mullis’s paper did not substantiate a meaningful scientific controversy.

“Professor McDonald said the effect of Professor Mullis’ answer was to

express confidence in the PCR system. Professor McDonald said that the controversy around HIV is not a controversy around whether PCR is a valid technology or technique. Professor Mullis had stated in a paper titled “A hypothetical disease of the immune system that may bear some relation to the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome” that there was a controversy as to whether and how HIV caused AIDS.In his paper, Professor Mullis observed:

The cells of an individual immune system could be so highly infected with latent viruses that were immunicologically distinct from one another as to result in an immune dysfunction resembling the acquired deficiency syndrome.

That was a theory propounded by Professor Mullis some ten years ago. Professor McDonald commented that the paper and the hypothesis postulated by Professor Mullis has not had any support from experts in the field of HIV/AIDS research.

Mr Borick QC contended that there is a continuing controversy in respect of whether HIV causes AIDS. He sought to support that contention by reference to the paper of Professor Mullis.

I consider that Professor Mullis’ views, as expressed in the paper ten years ago, are not supported by research. Over the past ten years since the paper was written, there is no evidence in any of the research that has been conducted in respect of the HIV/AIDS virus that the hypothesis of Professor Mullis has any scientific basis. The fact that a scientist who does not work or research specifically in the area of HIV/AIDS publishes an hypothesis does not establish that there is a genuine scientific debate about whether HIV causes AIDS.”

In essence, Judge Sulan committed a genetic fallacy—evaluating the validity of Mullis’s statements based solely on their source rather than their content—when he dismissed Mullis’s warnings and the arguments of the Perth Group regarding the HIV/AIDS debate. While Professor McDonald highlighted Mullis’s confidence in PCR as a technology, he overlooked Mullis’s crucial caution about the interpretation of its results. When the full exchange is considered in its proper context, along with the judge’s own words, it becomes evident that Mullis’s responses did not undermine the case. Unfortunately, his warnings about the limitations and potential misuse of PCR were disregarded.

Gunning for Clarity

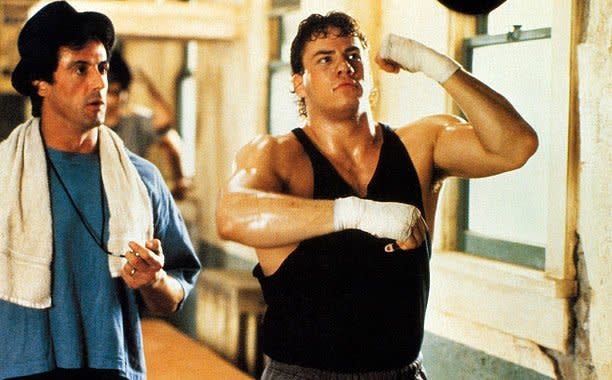

Hopefully, it is now clear that Kary Mullis did not support the use of PCR as a standalone diagnostic tool and that his 1985 patent, paper, 1998 book, and his email response in the 2007 Paranzee case have been misrepresented to suggest otherwise. Moreover, contrary to accusations from his detractors, Mullis did not intentionally contribute to anyone's incarceration. However, for those still harboring doubts, an email exchange with Tommy Morrison may further clarify Mullis’s stance.

Morrison, a two-time heavyweight boxing champion and co-star of Rocky V (as Tommy Gunn), was forced to retire in 1996 after testing positive for HIV, effectively ending his boxing career. However, in 2007, after testing negative for HIV on multiple occasions, Morrison launched an attempted comeback. Deeply concerned about whether existing tests could truly confirm “active HIV infection,” Morrison sought to challenge the mainstream narrative surrounding HIV/AIDS. It was through these efforts that he became acquainted with Kary Mullis, who shared his skepticism and provided insights into the limitations of PCR testing.

In an email to Tommy Morrison and his wife, Trisha, on May 5th, 2013, Kary Mullis clarified that PCR detects only small fragments of nucleic acid, not entire “viruses” or isolated organisms. While acknowledging the tool's remarkable sensitivity, he emphasized its limitations in confirming the presence of a complete “infectious virus.” Mullis explained that PCR results depend on the arbitrary choice of primers—short sequences designed to target specific regions of nucleic acid. While this ensures a degree of specificity, he highlighted that these primers only match small portions of a much larger sequence. This, combined with sequence variability among strains, makes the definition of “HIV positive” potentially ambiguous.

Mullis questioned the clinical and scientific implications of detecting HIV sequences, arguing that the mere presence of such sequences does not necessarily indicate disease or justify treatments that might carry significant risks. He compared PCR to diagnostic tools like prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, cautioning against making life-altering decisions based on single test results without corroborative evidence. Mullis's concerns reflected his broader skepticism about the overreliance on molecular tests like PCR in clinical and diagnostic contexts.

Dear Tommy (and Trisha),

A number of diseases are detected by the fact that using two sequences known to be contained in the DNA/RNA of some organism and running a PCR reaction, containing that DNA, a fragment of a known size predictable from the sequence of that organism will be produced. Further evidence (and much more credible) for the presence of that particular organism can be obtained by sequencing the fragment so obtained. An intermediate level of confidence can be obtained by so-called hybridization of the obtained fragment with a known sequence standard.

Most diseases can be diagnosed with some independent measure not related to DNA, but over the years DNA evidence has become a well-trusted method, and the mere presence of HIV DNA sequences in your blood is sufficient cause for most physicians to pronounce that you have AIDS and treat you for it. (You can have your prostate gland surgically removed based on higher than expected levels of prostate hormone, but I wouldn’t recommend it without collaborative evidence of rampant prostate cancer.)

The issue of assigning meaning to the evidence of HIV sequences in people is in my opinion the real outstanding issue, and my opinion is that there is insufficient evidence to conclude that such sequences are dangerous enough to the person (if at all) to justify a treatment that may very well be.

I have made myself clear on this issue for years. If I were to discover something which would make me think otherwise, I would feel honor-bound to make that very public.

Sadly anybody who can read and really wants to know about the issue of AIDS can read about it forever and still not know much about it as it is a highly contested issue and the financial consequences are immense. There are a large number of such issues in the world. Welcome to Earth.

PCR detects a very small segment of the nucleic acid which is part of the virus itself. The specific fragment detected is determined by the somewhat arbitrary choice of DNA primers used which become the ends of the amplified fragment (not virus isolation). They have to be in the sequence for it to be amplified in the first place, but they can be rather a small part of the total sequence. (Two to three hundred nucleotides is usually chosen out of several thousand in the total retrovirus). When incorporated in a cell the virus exists as DNA, when it is released from the cell in its infectious form it is RNA; which can be converted easily into DNA in the cell or in vitro for purposes of amplification. There are many sequence variations among the sequences called HIV. Any one of them can get you classed as what they consider HIV positive. And due to the tiny amounts of nucleic acid detectable after many cycles of PCR amplification (after 30 cycles one copy will get you about a billion copies) the test is super sensitive. Antibodies are detected by a non-PCR test called an EIisa. Elisa testing is not so specific as PCR as there are many antibodies not specific to HIV which may cross-react in this test. If a sequence amplifies with primers designed to HIV, it is HIV by definition. In order to amplify and produce a fragment of approximately the correct size the original sequence must hybridize with the primers, and therefore it must be at least a very close match (at least at the primer sites) to what has been defined as HIV. (now called HIV-AIDS in case there are any skeptics).

Kary Mullis

The “Hero” We Needed, But Not The One We Deserve.

"Joe Neilands called me one day and he said something like if you’ll start talking to the press about all kinds of issues and stuff, and I was starting to talk about AIDS…because they were using PCR to detect it, the HIV molecule, and I was going to a lot of those meetings and I was thinking these guys are on the wrong track and they’ve got blinders on them in a sense, he said if you just stop that, you know, you’re probably going to get the Nobel Prize but they don’t have to give it to you until you’re dead, so make it easier on yourself and just, I said you wouldn’t stop talking about something that you thought was important, would you Joe?”

-Kary Mullis

Nobel Prize Interview June 2005

Kary Mullis, like anyone, was not without flaws. He was a known womanizer and has been described by friends, colleagues, and critics as a hippie, acidhead, and hothead. One article called him a “contradictory figure—a rhapsodizing LSD-using Berkeley progressive,” while his own alumni publication described him as an “interpersonal wrecking ball” who frequently fought with others and engaged in adultery with lab mates. Beyond his personal flaws, Mullis is often criticized for not fully investigating the pseudoscientific foundational claims supporting the existence of “viruses” and “antibodies.” Others fault him for accepting the Nobel Prize and maintaining ties to the pharmaceutical industry, with some labeling him a “useful idiot,” “controlled opposition,” or even an “establishment shill.”

While it’s impossible to definitively classify Mullis as a hero or villain, one thing is clear: the current misuse of PCR as a diagnostic tool for “infectious” disease does not support the notion that he was a menace to society. Mullis consistently stated that using PCR in this way was a fundamental misuse of his invention. Thus, this misapplication of his invention cannot be held against him. He stressed that PCR could detect nearly anything in anyone, given its sensitivity, and highlighted the core problem: the interpretation and assignment of meaning to the detection of small, incomplete fragments of genetic material. A positive PCR test, according to Mullis, had no inherent diagnostic value. As he explained, such a result “doesn’t tell you that you’re sick, and it doesn’t tell you that the thing you ended up with really was going to hurt you or anything like that.” PCR was developed as a tool to detect and amplify nucleic acids in research, not to diagnose “infectious” disease in clinical settings.

Although Mullis is no longer alive to comment directly, his own words strongly suggest that he would have opposed how PCR was used during the “pandemic.” Specifically, he would have rejected the widespread reliance on PCR tests as the sole criterion for diagnosing “Covid.” Those who knew Mullis, such as the late Canadian researcher David Crowe, understood that he would have viewed the current use of PCR as a fundamental misuse of the technology.

“I’m sad that he isn’t here to defend his manufacturing technique. Kary did not invent a test. He invented a very powerful manufacturing technique that is being abused. What are the best applications for PCR? Not medical diagnostics. He knew that and he always said that.”

https://uncoverdc.com/2020/04/07/was-the-covid-19-test-meant-to-detect-a-virus

Kary Mullis's position is well-known and documented in various places. His views even aligned with the manufacturers of PCR tests for HIV, who acknowledged this inability to make diagnoses by including warnings in their inserts against using the PCR technology as a diagnostic tool.

Answer Received From Doctors & Scientists: The “PCR viral load” test is a DNA-fragment replicating test that was never meant to be used – and that still cannot be used – to detect “whole infectious virus”, as pointed out by the tests’ inventor himself, Dr. Kary Mullis. The manufacturers themselves acknowledge it is impossible to detect the presence of an “active infection” with the PCR “viral load” test and confirm this with this Disclaimer in their test packets:

PCR VIRAL LOAD TEST: The AMPLICOR HIV-1 (PCR “Viral Load”) MONITOR test, is not intended to be used as a screening test for HIV or as a diagnostic test to confirm the presence of HIV infection” (Roche, Amplicor HIV Monitor Test Kit).

The artus® HI Virus-1 RG RT-PCR Kit by QIAGEN also has a similar disclaimer:

The artus HI Virus-1 RG RT-PCR Kit is not intended to be used as a screening test for HIV or as a diagnostic test to confirm the presence of HIV infection.

As does the COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HIV-1 Test, version 2.0.

The COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 Test v2.0 is not intended for use as a screening test for the presence of HIV-1 in blood or blood products or as a diagnostic test to confirm the presence of HIV-1 infection.

Even the PCR tests used for “SARS-CoV-2,” such as the CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel, acknowledged that they could not determine the presence of an “infectious virus” or establish that what was detected caused disease, rendering a positive result essentially meaningless.

“Detection of viral RNA may not indicate the presence of infectious virus or that 2019-nCoV is the causative agent for clinical symptoms.”

The resurgence of Kary Mullis’s views on PCR came at a critical moment during the “pandemic,” as people sought reasons to challenge the official narrative. Despite his flaws, Mullis emerged as a rallying figure, particularly in opposition to the widespread use of PCR testing as a requirement for work or travel as well as a harsh critic of Anthony Fauci. In the midst of a pandemic of PCR testing, many turned to Mullis as a credible voice of authority, given his well-documented opposition to using his invention as the sole means to diagnose “infectious” disease.

Mullis’s words became a powerful tool for challenging the official narrative. His stance helped awaken many to the misuse of PCR testing and the broader fraud being perpetrated on the population. The fact that the inventor of PCR openly criticized its use for diagnosing “infectious” disease is profoundly damaging to the official “Covid-19” narrative and underscores what he likely would have seen as the widespread misuse of PCR technology. Like it or not, as a Nobel Laureate and the creator of PCR, Kary Mullis’s voice carries significant weight. For those unfamiliar with the debate, discovering that Mullis opposed the diagnostic use of his invention is a powerful revelation.

As his views successfully broke through the fear-driven propaganda to help wake up many by challenging the official narrative, an important question arises: why are some so determined to misrepresent Mullis’s stance and downplay his opposition to PCR’s diagnostic use? What purpose is served by distorting or obscuring his position, especially when clear evidence supports it? Is it an attempt to undermine his credibility and frame him as a villain to protect the prevailing narrative?

Discrediting Mullis as a “bad actor,” “clown,” or “fraud” serves to protect the mainstream narrative by silencing the man who best understood the limitations of his creation. Misrepresenting his stance erases one of the most compelling arguments for the layperson against using PCR as a diagnostic tool for “infectious” disease. These efforts to mischaracterize him appear to be calculated attempts to suppress this inconvenient truth, undermining a key challenge to the widespread reliance on PCR during the “pandemic.”

Kary Mullis may not have been a perfect person and, unfortunately, held onto some beliefs aligned with mainstream pharmaceutical narratives. While he deserves criticism for not fully following through with the logical process that led him to question both the HIV/AIDS hypothesis and climate change, his willingness to challenge foundational claims was nonetheless significant. He was a powerful voice against the HIV/AIDS hypothesis, calling it “one hell of a mistake.” He was a fierce critic of Anthony Fauci, the man who spearheaded both the HIV/AIDS and the “Covid” fear campaigns, stating that Fauci “didn't know anything about anything…and I'll say that to his face.” Mullis also challenged his own “scientific” fraternity, stating that “there are no old wise men up there at the top of science…making sure that we don't do somethin’ really dumb” and that the “academy of science is just a bunch of idiots just like everybody else.”

For those seeking guidance from an authoritative figure, Kary Mullis stands as a valid source, and his words have helped awaken many to the frauds we now face. Misrepresenting or misinterpreting his views is a disservice to those who could learn from him, as it obscures the truth he sought to reveal.

Ultimately, how one views Mullis depends on their perspective. While he may not fit the idealized image of a hero, he is far from the villain others have tried to portray him as. The truth likely lies somewhere in between. Regardless of how he is characterized, it wouldn’t matter even if Mullis were exactly as his detractors claim. In the grand scheme, the debate over his character and motives is secondary.

What truly matters is that the words left behind of an authoritative figure within the mainstream paradigm have been wielded effectively to challenge and expose its flaws.

In that sense, Kary Mullis gets a heroic last act—even if it may have been unintended.

Written interviews and articles with Kary Mullis:

Kary Mullis: The Great Gene Machine Interviewed April 1992 by Anthony Liversidge

AIDS; Words from the Front by Celia Farber from Spin July 1994

Rethinking AIDS March/April 1994

THE MEDICAL ESTABLISHMENT VS. THE TRUTH Book Excerpt by Kary Mullis Penthouse Sept. 1998

WHAT CAUSES AIDS?

It's An Open Question by Charles A. Thomas Jr., Kary B. Mullis, & Phillip E. Johnson Reason June 1994

DISSENTING ON AIDS: THE CASE AGAINST THE HIV-CAUSES-AIDS HYPOTHESIS by Kary B. Mullis, Phillip E. Johnson & Charles A. Thomas Jr. The San Diego Union-Tribune 15 May 1994

Scientist at Work/Kary Mullis; After the 'Eureka,' a Nobelist Drops Out by Nicholas Wade Sept. 15, 1998

Kary B. Mullis Nobel Prize Interview June 2005

Relevant video interviews with Kary Mullis:

Kary Mullis The full interview by Gary Null

Kary Mullis: Celebrating the scientific experiment

Dean Rotbart interview Dr. Kary Mullis

Dr Kary Mullis inventor of pcr test questions the intention behind viral diseases

Dr. Kary B. Mullis | Conversations with Scientists & Astronauts

I've been following this issue for years. I have concluded that most of the same people who villainize him for "believing in viruses" and being unclear about the nature and consequences of his own invention remind me of the pearl-clutching progressives and 'liberals' who despise America's founders for owning slaves when they would have certainly thought nothing of it had they lived in those times. Or railing against Nazis without understanding that, statistically, most all of them would be members of the party if they lived in that milieu. Mullis invented a useful tool, and warned colleagues sometimes to the point of tears NOT to use it for diagnostic purposes. His death is suspicious. Cut him some slack. I vote Hero.

Per his request, I am posting a comment that I received via e-mail from Val Turner of the Perth Group.

The following is taken from The Perth Group unpublished manuscript “HIV-A virus like no other” (search for Racaniello at http://www.theperthgroup.com/HIV/TPGVirusLikeNoOther.pdf).

“As seductive as molecular biology has become, it is important not to equate it with virology. DNA, RNA and proteins are large molecules composed of repeated subunits (polymers). Viruses are infectious particles made of nucleic acid, proteins and other molecules. As Vincent Racaniello teaches his students “A virus is not the same as a virus [nucleic acid] sequence. If you isolate a 200 nucleotide sequence from a specimen that does not mean that the virus is present”. 180 In fact this matter was specifically addressed in the Parenzee leave for appeal hearing 181 when the Prosecutor presented a paper entitled “Sequence-Based Identification of Microbial Pathogens: a Reconsideration of Koch’s Postulates” as evidence that genetic methods can be used to prove a virus exists. During cross-examination one of us (EPE) read to the court what the authors stated in their paper: “…with only amplified sequence available, the biological role or even existence of these inferred microorganisms remains unclear” (emphasis ours). Ultimately, the HIV experts, including Gallo testified, that to identify the viral genome the virus particles must be purified. http://theperthgroup.com/OTHER/ENVCommentary.pdf#page=37 ”

In summary, Mullis made the point, “PCR allows a scientist to turn a minute scrap of stuff into a helluva lot of stuff”. However, PCR does not tell you the provenance of that stuff. For those wishing to know more about this chronically neglected problem, please consider Eleni Papadopulos’ magnum opus, The Isolation of HIV: Has it really been achieved”.

http://www.theperthgroup.com/CONTINUUM/PapadopolousReallyAchieved1996.pdf

REFERENCES

180. This video virology lecture is no longer available. Racaniello V. What is a virus? 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-C0r_-1DufM However it is at the WayBack Machine. https://web.archive.org/web/20250000000000*/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-C0r_-1DufM

In 2025 Racaniello says the same thing in the latest iteration of the same lecture. https://youtu.be/3pX0x3mC4Io?t=3131

Addressing AI and virology in 2025 Racaniello says: “The point is they were able to identify many new RNA viruses that hadn’t been found before −161,000 putative RNA virus species, which is huge. Now, this is an example of how AI is transforming virology. They say putative, because they have just a sequence, right?. They don’t have virus so they don’t know if the virus actually exists…because just having a sequence doesn’t prove that there is a virus around”.

181. The Parenzee Case. In 2006/2007 Andre Chad Parenzee made an application for leave to appeal to his earlier conviction for endangering the lives of three women following “unprotected sexual intercourse…when he knew he was infected with the virus HIV”. (R v PARENZEE [2007] Supreme Court of South Australia.

https://jade.io/j/?a=outline&id=8353). http://www.tig.org.za/Transcript_Perth_Group_evidence.htm

182. Fredericks DN, Relman DA. Sequence-based identification of microbial pathogens: a reconsideration of Koch’s postulates. Clin Microbiol Rev 1996. 9:18-33.