An Inquiry into the Logical Basis of the Germ Theory

The germ “theory:" a scientific foundation or a logical fallacy?

To those familiar with my work, it comes as no surprise that I take great interest in highlighting the forgotten voices from the formative years of germ “theory” and virology—those who examined the rise of these pseudoscientific fields with critical eyes. These individuals had front-row seats to history, and they witnessed firsthand the unscientific, contradictory foundations that shaped our modern beliefs about health, disease, and wellness. They recognized the manipulation by vested interests and warned against the manufactured acceptance of germ “theory” by a fearful, uninformed public. And they spoke out—attempting to avert what they foresaw as a grave disaster.

Amongst the earliest of these voices was the great French chemist Antoine Béchamp, a rival of Pasteur and proponent of the competing terrain theory. He astutely recognized how the public had been misled in the preface to his 1867 publication La Théorie du Microzyma (translation from Bechamp or Pasteur: A Lost Chapter in the History of Biology):

“The general public, however intelligent, are struck only by that which it takes little trouble to understand. They have been told that the interior of the body is something more or less like the contents of a vessel filled with wine, and that this interior is not injured – that we do not become ill, except when germs, originally created morbid, penetrate into it from without, and then become microbes.

The public do not know whether this is true; they do not even know what a microbe is, but they take it on the word of the master; they believe it because it is simple and easy to understand; they believe and they repeat that the microbe makes us ill without inquiring further, because they have not the leisure – nor, perhaps, the capacity – to probe to the depths that which they are asked to believe.”

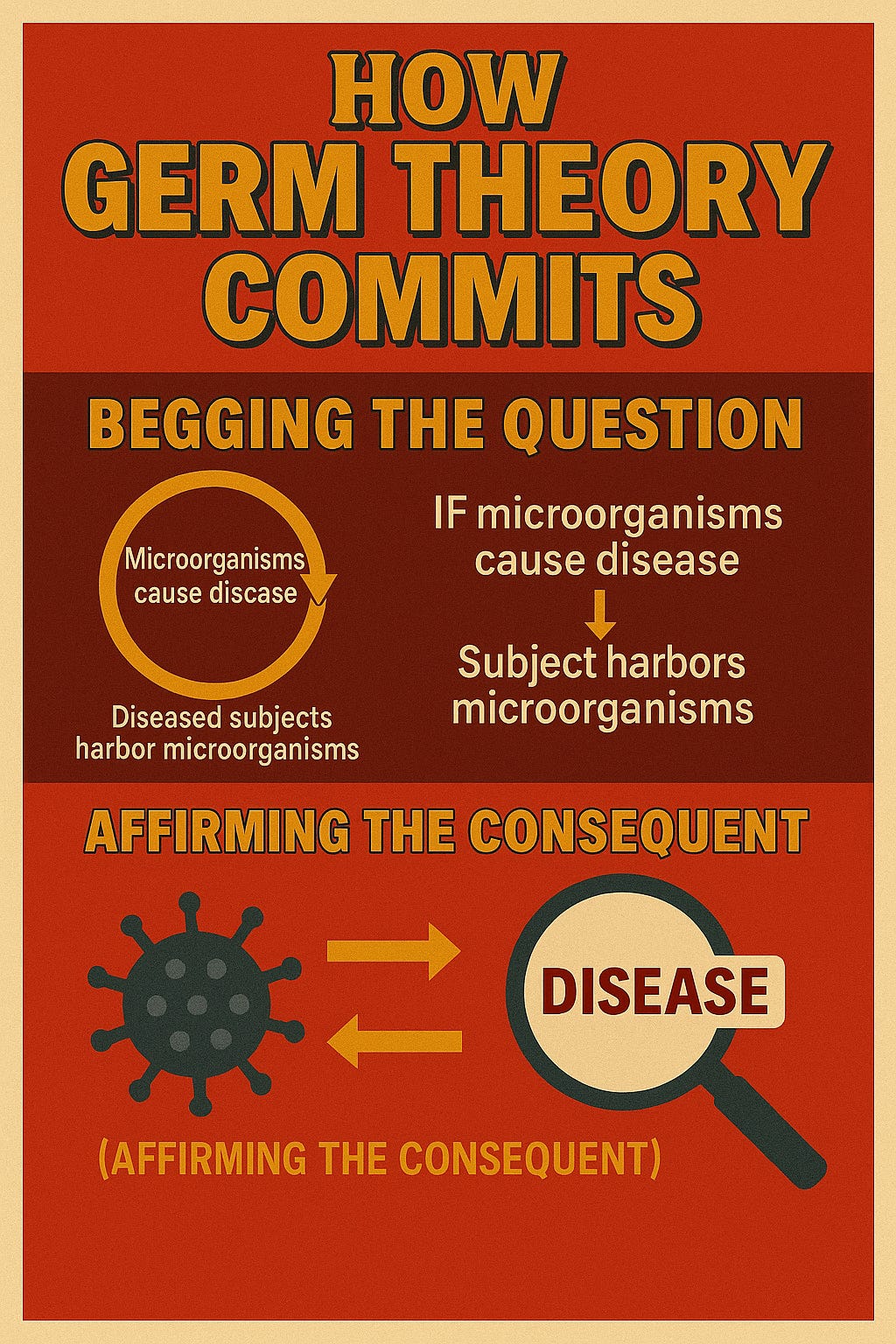

Decades before germ “theory” reached mainstream dominance, American physician Dr. Edward P. Hurd raised concerns about its flawed logic. In his 1874 paper On the Germ Theory of Disease, Hurd questioned whether germs were truly the cause of disease rather than mere byproducts of it. He specifically criticized the fallacy of affirming the consequent—the mistaken belief that if cause A (a germ) is always found with effect B (a disease), then A must have caused B. Hurd pointed out that simply showing a germ is always present with a disease does not prove causation. To establish a valid causal link, one must introduce the germ into a healthy environment and observe whether the disease follows—something germ theorists had failed to do:

“There is no proof that all that have as yet been found are not accompaniments, or effects, and not causes of the diseased conditions with which they are found associated. Halber has not yet completed the cycle of proof necessary to establish tho causal nexus between one single disease and the micrococcus found witli that disease. He has relied exclusively on what logicians call the method of agreement—the method of difference he has not tried. It is of little account for him to show that the supposed cause A always exists with the disease B, and hence B is the effect of A. Into a preexisting set of circumstances where B does not exist he must introduce A and produce the disease. This he has not attempted, and hence his speculations are of little worth.”

Another outspoken critic was Lionel S. Beale, pioneer of the microscope for medicine, who warned in 1878 how speculative claims—like germs causing disease—can rapidly gain traction through repetition and institutional backing. A few “authorities” assert, others repeat, officials endorse, and suddenly the world believes what was never proven:

“It is curious to observe how very easily in these days an untenable doctrine may be forced into notoriety, and taught far and wide as if it were actually demonstrated truth. A few authorities perhaps in Germany graphically portray what they please to call the results of observations, and after marshalling before the reader certain facts and arguments, remark that the evidence is perfectly conclusive in favour, say, of the view that certain contagious diseases are due to microzymes. Papers, with "new observations," soon follow, and confirm the original statement in every particular. Pupils, friends, admirers, accept and diffuse the new doctrine. Abstracts and memoirs multiply, and the conclusions arrived at abroad are supported and promulgated here, under the patronage of a government official, and published in a blue book. Those unacquainted with the art and mystery of transforming arbitrary assertions into scientific conclusions are easily convinced that the whole scientific world is agreed upon this one question at any rate, while in point of fact the speculative and far-fetched arguments would not have withstood careful and intelligent examination.”

Renowned British surgeon Dr. Lawson Tait, considered the greatest abdominal surgeon of his time, openly dismissed the fear of germs, once stating he would prefer a mass of germs over a wet sponge during surgery. In the 1887 paper An Address on the Development of Surgery and the Germ Theory, he declared:

“Let me only say that the best of all proof of the fallacy of their assertions is the fact that every attempt to elevate the germ facts of putrefaction into a germ theory of disease has miserably failed, and has failed nowhere so conspicuously as when obtruded into the realms of the treatment of disease.”

In the 1894 paper A Criticism of the “Germ Theory of Disease,” Based on the Baconian Method, Dr. Tait wrote that the germ “theory” wasn’t a theory or even a hypothesis. It was just a jumble of facts—some true, many false— with no coherent explanation behind them. No working hypothesis. No actual theory. It was simply dogma:

“The germ theory of disease is not a theory at all. It is not even a hypothesis. It is a mere congeries of facts some truly stated, but mixed up with a far greater bulk inaccurately (indeed, untruly stated), upon which not even a working hypotheses has yet been suggested, far less a theory built.”

In 1913, Dr. Herbert Snow—a surgeon, medical writer, and cancer researcher—published the article The Germ Theory of Disease (which I reprinted with additional commentary here) in which he exposed the lack of scientific proof that any microbe causes disease. His opening remarks are scathing:

“The Germ Theory of Disease, so prominent in medical literature and practice, began with the efforts of the chemist Pasteur to apply to human, maladies—which, not being a doctor, he only knew academically—deductions drawn from the phenomenoa he had observed in fermentation. There has never been anything approaching scientific proof of the casual association of micro-organisms with disease; and in most instances wherein such an association has been pretended, there is abundant evidence emphatically contradicting that view. Yet most unfortunately this lame and defective theory has become the foundation of a very extensive system of quackery, in the prosecution of which millions of capital are embarked, and no expense spared to hoodwink the public with the more credulous members of the Medical Faculty. It may then not be out of place to survey, as fudicially as may be, the position in which the Germ Theory now stands; with the ill consequences very conspicuously resulting from its premature adoption as a proven axiom of Science.”

By the 1920s, cracks in the germ “theory” narrative were becoming harder to ignore. In Principles and Practice of Naturopathy (1925), Dr. E.W. Cordingley, M.D., N.D., A.M., observed that the germ “theory” of disease was weakening and due to be thrown away:

"Medical doctors are working on the germ theory of disease...But the germ theory is already weakening and is due for being thrown aside. Dr. Fraser of Canada and Dr. Powell of California have experimented with billions of germs of all varieties, but they have been unable to produce a single disease by the introduction of germs into human subjects. Dr. Waite tried for years to prove the germ theory, but he could not do so. During the World War an experiment was conducted at Gallop's Island Massachusetts, in which millions of influenza germs were injected into over one hundred men at the Government hospital, and no one got the flu. Germs are scavengers.”

Dr. Cordingley referenced the experiments of Dr. Thomas Powell and Dr. John B. Fraser, both of whom experimented on themselves and others with billions of pure cultures of the most “dangerous” germs of all varieties, and were unable to produce a single disease through these efforts.

Dr. Powell—who asserted he was in direct opposition to “the greatest delusion of the world’s history” and that “scientists of the world are at fault in their germ theories”—stated:

“Before going into the details of my experiments with the germs of virulent diseases. I want to preface my statements with the explanation that I do not declare the germs to be harmless in all cases. What I do say is that a person to whom the germs of a particular disease are likely to prove dangerous must have a predisposition towards that particular disease, such predisposition being either hereditory or acquired. Given a man or woman with no such predisposition, and I claim that the deadliest germs are powerless to harm them. They can enter the sick chamber without fear of contracting disease, or even do as I have done, take the living germ into their system and suffer no harm. My experiments have proved the truth of my theory. “I claim that disease germs are utterly incapable of successfully assailing the tissues of the living body; that they are the results and not the cause of disease; that they are not in the least inimical to the life or health of the body; that, on the contrary, it is their peculiar function to rescue the living organism, whether of man or beast, from impending injury or destruction. They accomplish this by bringing about the decomposition of that obstructing matter which constitutes predisposition to disease, and cause it to be passed out by tlie blood.”

Dr. Fraser, through his experiments a few decades later, came to a similar conclusion: germs were the result of, and not the cause of, disease:

“If you examine the standard works on bacteriology you find no positive proofs given, that germs, if taken in food or drink, are harmful.”

“The assumptions that because germs are found with disease they are the cause of it, and that if injected germs will cause disease, inhaled or ingested germs will do the same, is surely a “foundation of sand.”

Dr. Fraser presented a summary of the facts:

1. That germs follow the onset of disease.

2. That many diseases have a chemical origin.

3. That germs may be inhaled or ingested without harm.

In the 1933 book The Golden Calf: An Exposure of Vaccine Therapy, author Charles W. Forward argued that no other hypothesis had ever been built on a flimsier foundation than the germ “theory” of disease. He claimed it had destroyed medicine as an art, failed to re-establish it as a science, and instead transformed it into a commercial enterprise that systematically exploited both sickness and the fear of sickness for profit:

“It is doubtful if any superstructure in the shape of hypothesis has ever been raised upon flimsier basis of fact than the theory of the specific "germ" as the causative factor in disease, the theory that each disease has its own particular bacterium, and that, in the words of Florence Nightingale, as quoted by Tyndall, the matter of each contagious disease reproduces itself as rigidly as if it were dog or cat.”

“This so-called "Germ" Theory has brought about a revolution in medical treatment. It has destroyed medicine as an art, and failed to re-establish it as a science. By means of it medicine has become commercialized, and sickness and the fear of sickness are systematically exploited for pecuniary profit.”

American physician Dr. William Howard Hay offered a similar critique in his 1940 essay Who Are The Quacks?, an eight-page exposé critically examining the medical industry while challenging the germ “theory” of Pasteur and Koch. He pointed out that not a single germ had ever fulfilled Koch’s Postulates—the widely accepted criteria required to establish a microbe as the cause of a specific disease—and argued that Pasteur’s promotion of germ “theory” had set medical science back by sixty years:

“This theory of germs as the cause of disease was analyzed by Prof. Robert Koch, who formulated a dictum, accepted by the scientists of his time, that must be met in order to fix on the germ as a cause of disease.

According to this dictum if the germ caused the disease it must be present in every case of this disease; it must not be present except in conjunction with the disease, it must be susceptible of separate cultivation in proper media outside the body, and finally, it must be susceptible of transplantation again in the human body, where it must infallibly produce the same disease.

The germ theory does not meet a single one of these conditions infallibly, the germ frequently being absent from diseased conditions which are attributed to it; being generally present in bodies in which the disease attributed to it is most conspicuous by its absence! And while germs are susceptible to cultivation outside the body, in suitable media, yet they are subject to mutation as the medium is changed in character, and, if again introduced into the body, they do not always infallibly cause the disease they are supposed to cause, generally not causing disease of any kind whatsoever.

Pasteur has already set us back sixty years by his advertising of the germ theory, and if we go back to the teachings of Bechamp, recognizing the microzyma as the prime cause, and the germ as a development of a biochemical nature, result of the condition of the body, transformed into a necessary scavenger to remove from the body objectionable matter, we will perhaps regain the ground lost for over sixty years, and be able to concentrate our attention on the soil conditions in the body, not on the harmless germ scavenger.”

In the book The Medical Mischief, You Say!: Degerminating the Germ Theory, a 1947 passage from The Homeopathic Review by Royal E. S. Hayes, M.D was reprinted. Hayes did not hold back, describing germ “theory” as “the greatest travesty on science,” “a ghastly medical farce,” and “the biggest hoax” the medical profession ever embraced:

“The germ theory of disease is the greatest travesty on science that was ever stumbled over during this semicivilized age; the most ghastly medical farce in which the human mass ever played its part; the biggest hoax the medical profession ever took in after with little hesitation and no mastication.”

Even within mainstream science, doubts persisted. By the 1950s, prominent immunologist René Dubos—himself a supporter of germ “theory”—warned against its overreach in his essay Second Thoughts on the Germ Theory (which I examined here). Dubos argued that the “theory” was oversimplified and rarely aligned with the actual facts of disease. He likened it to a cult—one that ignored inconsistencies and showed little concern for weak or contradictory evidence. He also noted how historians often glossed over the fact that many clinical observations by physicians and hygienists could not be fully explained by the germ “theory” of disease:

“The germ theory of disease has a quality of obviousness and lucidity which makes it equally satisfying to a schoolboy and to a trained physician. A virulent microbe reaches a susceptible host, multiplies in its tissues and thereby causes symptoms, lesions and at times death. What concept could be more reasonable and easier to grasp? In reality, however, this view of the relation between patient and microbe is so oversimplified that it rarely fits the facts of disease. Indeed, it corresponds almost to a cult-generated by a few miracles, undisturbed by inconsistencies and not too exacting about evidence.

Historians usually give a biased account of the heated controversy that preceded the triumph of the germ theory of disease in the 1870s. They barely mention the arguments of those physicians and hygienists who held that clinical observations could not be completely explained by equating microbe with causation of disease. The critics of Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch pointed out that healthy men or animals were often found to be harboring virulent bacteria, and that the persons who fell victim to microbial disease were most commonly those debilitated by physiological disturbances. Was it not possible, they argued, that the bacteria were only the secondary cause of disease-opportunistic invaders of tissues already weakened by crumbling defenses?”

Likewise, in 1968, Dr. Gordon T. Stewart, professor of Epidemiology and Pathology at the University of North Carolina—and himself a proponent of the germ “theory” of disease—wrote in his article Limitations of the Germ Theory that it was a gross oversimplification, unable to account for exceptions and anomalies. Over time, he warned, it had become an unquestioned and uncritically accepted dogma:

“The germ theory of disease—infectious disease is primarily caused by transmission of an organism from one host to another—is a gross oversimplification. It accords with the basic facts that infection without an organism is impossible and that transmissible organisms can cause disease; but it does not explain the exceptions and anomalies. The germ theory has become a dogma because it neglects the many other factors which have a part to play in deciding whether the host/germ/environment complex is to lead to infection. Among these are susceptibility, genetic constitution, behaviour, and socioeconomic determinants.”

These are but a few examples of voices that spanned a century, and there are many others that have been uncovered. They were not fringe thinkers, but trained scientists, physicians, and observers who questioned the legitimacy of a “theory” that quickly became dogma. They warned—correctly—that correlation was mistaken for causation, that authority replaced evidence, and that this error would reshape medicine for profit rather than for healing. Their words remain as relevant now as ever.

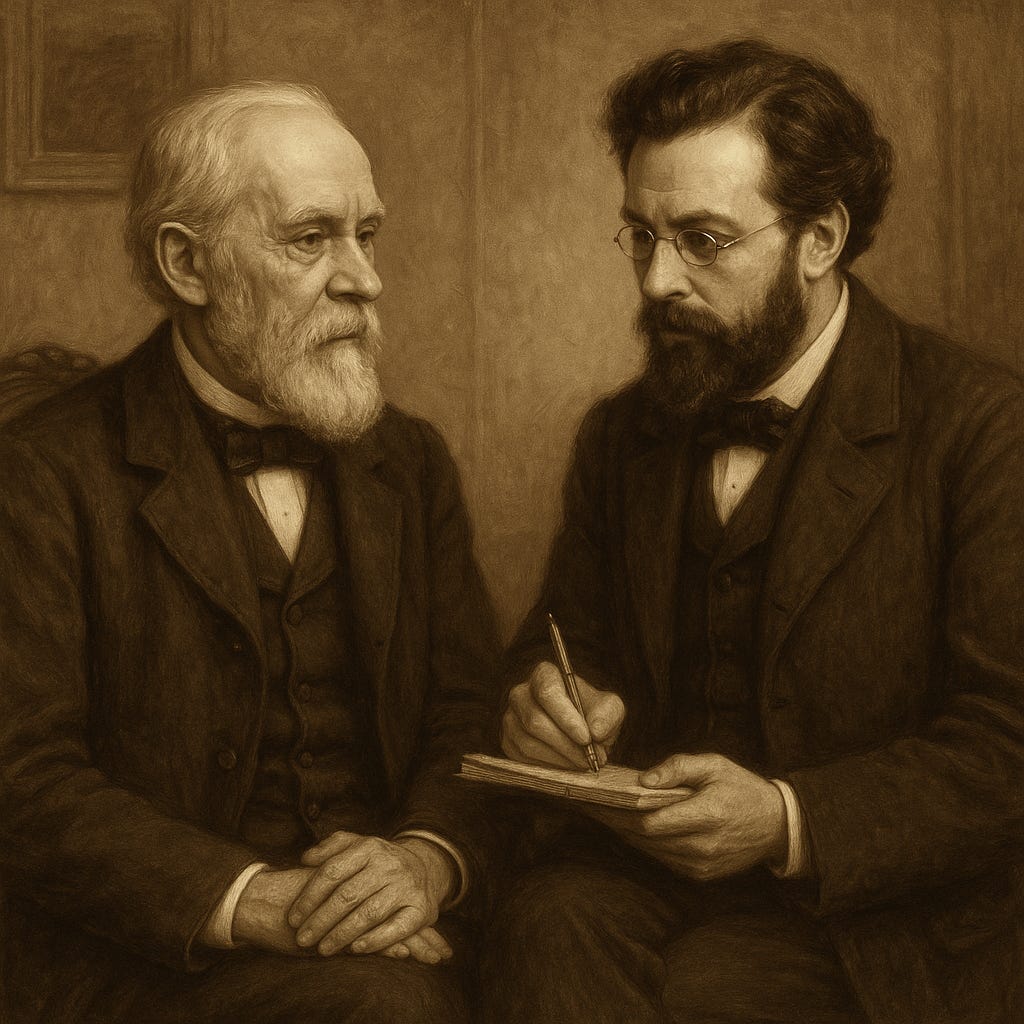

One important voice I’ve deliberately left out of the previous quotes is that of Dr. Montague R. Leverson—not because his contributions were minor, but because they merit closer attention. While many of the individuals quoted above offered sharp and insightful critiques of germ “theory,” Dr. Leverson played a unique and indispensable role in preserving the work of one of its most formidable scientific challengers: Antoine Béchamp.

It is largely thanks to Dr. Montague Leverson that Béchamp’s achievements—and the controversy surrounding Pasteur’s appropriation of them—are known at all today, particularly in the English-speaking world. Upon encountering Béchamp’s writings in New York, Leverson immediately recognized their significance and, as revealed in the preface of his subsequent translation of Bechamp's The Blood And Its Third Element, began a regular correspondence with the French chemist regarding his research and remarkable discoveries. He eventually traveled to Paris with the specific intention of meeting Professor Béchamp in person—just weeks before the latter’s death.

There, over the course of fourteen days of nearly daily conversations, Leverson heard directly from Béchamp about the plagiarism committed by Pasteur and the deeper scientific truths that had been buried by the rise of germ “theory.” Deeply moved by what he learned, Leverson became committed to restoring Béchamp’s rightful place in history and to sharing the suppressed insights he had received with the world.

His meticulous notes from these meetings were originally intended to serve as a special chapter in his own comprehensive work, Inoculations and Their Relations to Pathology, a book he had been researching and writing exclusively for over fourteen years. However, after Béchamp’s death, Dr. Leverson concluded that it would better serve the English-speaking public if Béchamp’s discoveries were published more directly, alongside translations of his original work.

Following Béchamp’s funeral in Paris in 1908, Leverson relocated to England, where he met Ethel Douglas Hume a few years later. He spoke at length with her about Béchamp’s scientific achievements and the fraud he believed had been committed by Pasteur. These conversations sparked Hume’s interest and led her to investigate the matter further.

Eventually, Mr. A. H. H. Lupton shared Dr. Leverson’s unfinished manuscript with Hume—a disorganized collection of quotations from Béchamp’s writings, presented without references or structure. Though the material was not publishable in its original form, Hume agreed to take on the task of editing it. The project ultimately evolved into her own widely read book, Bechamp or Pasteur: A Lost Chapter in the History of Biology—still the most thorough English-language work on the subject.

In this way, Dr. Leverson served as the critical link between Béchamp and Hume. Without his initiative and dedication, much of Béchamp’s work may have remained buried in obscurity, and the historical record even more distorted. His role was not only that of a messenger, but of a bridge between generations—preserving a suppressed legacy so it might be rediscovered in our time.

Just as Dr. Leverson preserved the legacy of Antoine Béchamp for a new generation of truth-seekers, I hope to do the same for Dr. Leverson. His own writings—particularly An Inquiry into the Logical Basis of the Germ Theory—deserve renewed attention. In presenting his work here, along with supplemental commentary, I aim to highlight the clarity and depth of his reasoning. Leverson didn’t merely reject the assumptions of germ “theory”—he dismantled them through methodical, logical critique that remains strikingly relevant in an age where belief still too often overshadows proof. Like Béchamp’s, his voice was nearly erased. But truth has a way of resurfacing—and now is the time to let it speak again.

Montague Leverson was already a vocal critic of the germ “theory” of disease long before he became a physician. On December 2, 1885, he was appointed secretary of the newly incorporated Anti-Vaccination Society of America. A true Renaissance man, Leverson had previously been a Colorado rancher, a California state assemblyman, and a leading figure in the Brooklyn Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League. Remarkably, he earned his medical degree from Baltimore Medical College in 1893 at the age of sixty-three—bringing to the field not just academic training, but a lifetime of critical thinking and civic engagement. Armed with both medical training and a long-standing skepticism of mainstream dogma, Leverson was uniquely positioned to confront the “theory” on its own terms. In April 1898, he did just that—presenting a paper before the Homoeopathic Union of Brooklyn challenging the logical basis of the germ “theory” of disease.

What initially drew me to this paper was Dr. Leverson’s direct and unapologetic focus on logic—or more precisely, the absence of it—in the germ “theory” of disease. Anyone familiar with my work knows that I continually emphasize the importance of sound reasoning when evaluating germ “theory” and modern virology. I owe a debt of gratitude to the brilliant Dr. Jordan Grant for helping me hone this crucial line of critique, which continues to reveal the pseudoscientific foundations on which these claims rest. Pointing out logical fallacies is not mere pedantry; it is essential for exposing when a claim lacks genuine explanatory power. Without logical consistency, any model becomes unfalsifiable, unscientific, and ultimately indistinguishable from superstition.

This is precisely what makes Dr. Leverson’s approach so powerful: he didn’t merely argue from experience, intuition, or anecdote. Nor did he stop at pointing out inconsistencies or failed experiments. He approached the germ “theory” on its own terms, holding it accountable to the very logic it claimed to uphold. This is the mark of a serious thinker—someone who understood that if a theory collapses under the weight of its internal contradictions, it requires no external refutation. It fails on logical grounds alone.

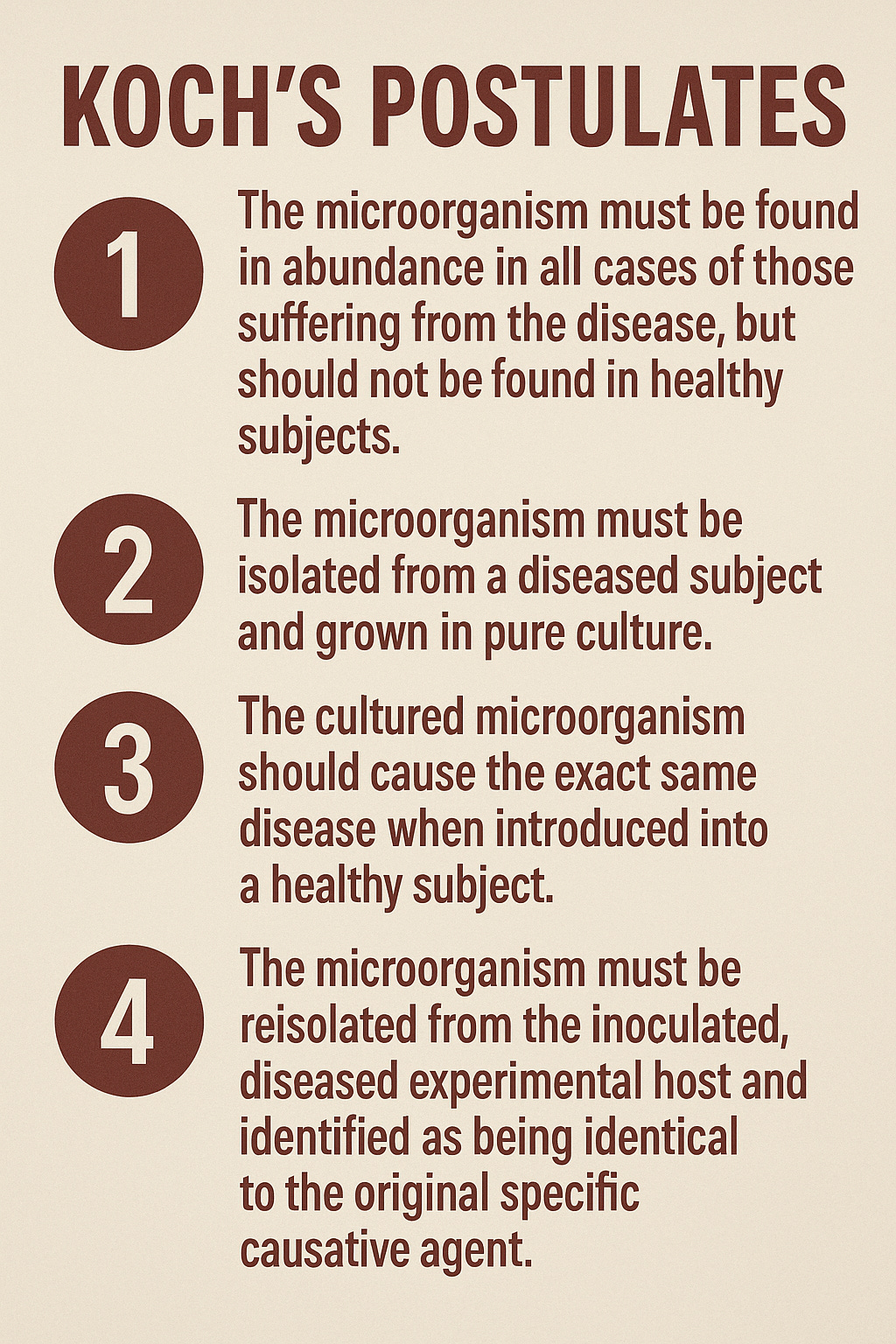

One particularly important logical benchmark for evaluating any claim of causation in “infectious” disease is the satisfaction of Koch’s Postulates—a set of logical criteria seeking to establish whether a specific microbe actually causes a specific disease. Popularized by Robert Koch in the 1880s, these postulates became the gold standard for proving microbial causality. Dr. Leverson understood this well. In fact, the entire premise of his 1898 paper, An Inquiry into the Logical Basis of the Germ Theory, is to investigate whether the germ “theory” holds up when judged by the very criteria it is said to rest upon.

To do this, Leverson turned to a summary of Koch’s Postulates found in the 1891 edition of Dr. Fraenkel’s Text-Book of Bacteriology, translated by Dr. J. H. Linsley. He used this version because it claimed to present the “fixed and definite rules” of germ causation with “exactness and precision.” It is from these explicit rules that Dr. Leverson launched his methodical dismantling of the germ “theory.”

An Inquiry into the Logical Basis of the Germ Theory

M. R. Leverson, M. D., Fort Hamilton, L. L, N. Y.

(Paper read before the Homoeopathic Union Brooklyn, April, 1898.)

For the purpose of investigating the logical basis of any theory, it is essential that that theory should be considered in the very words of its author, wherever that is possible. I therefore propose to consider the germ theory in the words of Dr. Fraenkel according to the “fixed and definite rules laid down with exactness and precision by Koch.” (See Text Book of Bacteriology, by Fraenkel, translated by Dr. J. H. Linsley, edition of 1891, pp. 150-1.)

These rules, as stated by Dr. Fraenkel, are; that for a micro-organism to be recognized as a specific agent in the production of pathological alterations it should fulfill three conditions, as follows:

“First. It must be proved to be present in all cases of the disease in question.

“Second. It must further be present in this disease and in no other; since otherwise it could not produce a specific definite action.

“Third. A specific micro-organism must occur in such quantities and so distributed within the tissues that all the symptoms of the disease may be clearly attributed to it.”

While the three postulates listed by Dr. Fraenkel resemble Koch’s Postulates, his version primarily elaborates on what is traditionally considered the first of Koch’s four conditions. It does not fully encompass the complete framework that came to be known as Koch’s Postulates. The standard version is typically stated as follows:

Nevertheless, Fraenkel’s three-point summary gave Dr. Leverson a logical entry point for evaluating the germ “theory” on its own terms. But in citing only those three criteria, Leverson left out other important admissions made by Fraenkel in the very same text that require examination before proceeding with his rebuttal—beginning with the fundamental uncertainty about the origin of microbes found in sick individuals:

“The pathogenic bacteria are by far the most interesting to us. Wherever and whenever we find micro-organisms, in the human body or in animals, the question always arises whether we have this variety of micro-organisms or not. The answer is often difficult and must always be according to fixed and definite rules which were first laid down with exactness and precision by Koch many years ago.

These rules require that a micro-organism, to be recognized as a specific agent in the production of pathological alterations, should fulfil three conditions:

These rules, Fraenkel wrote, were necessary to determine whether a given microorganism was indeed the specific cause of pathological changes. Regarding the first postulate—that the microorganism must be present in all cases of the disease—he asserted that this was so fundamental, it scarcely required justification:

First, it must be proved to be present in all cases of the disease in question.

This is a matter of course, and scarcely requires a justification; for if the disease can occur without the bacterium, the latter is not unconditionally necessary and cannot be regarded as specific.

In other words, Fraenkel acknowledged that if even a single genuine case of the disease occurs without the presence of the supposed “pathogen,” then that “pathogen” cannot be considered the necessary, specific cause of the disease. This logical requirement—so basic and seemingly obvious—forms the very first pillar of Koch’s Postulates. It is grounded in the principle of falsifiability: if a cause is truly necessary, then its absence must rule out the effect. To put it simply, a cause that does not always accompany the effect cannot be its necessary cause. This is not a controversial or obscure philosophical position—it’s the kind of reasoning used in everyday life. If someone claims that rain always causes wet streets, but we find dry pavement during a storm, then the claim is disproven. Yet in medical science, this foundational rule is routinely bypassed or ignored, despite its central role in distinguishing correlation from causation. Accepting exceptions without explanation undermines not only the germ “theory” but the very logic by which scientific claims are evaluated.

Fraenkel’s next criterion is equally clear: the microorganism must not be found in any other disease. This, too, reflects a basic logical principle—one tied to the idea of specificity in causal reasoning. If a germ is said to be the specific cause of disease X, then it cannot also appear in unrelated conditions, such as disease Y or Z, let alone in healthy individuals. To allow such overlap would render the germ’s association with disease X meaningless. The logic here is analogous to saying that a particular key opens only one specific lock; if it’s found to open many locks—or worse, if it’s found in doors that are already open—then its status as the sole key is falsified.

In the context of disease, if a supposed “pathogen” is found across multiple, distinct illnesses—or even in healthy individuals—it cannot logically be considered the specific cause of any one of them. Its presence may still be interesting, but it becomes irrelevant as proof of causation. Yet here again, Fraenkel admits that this standard is frequently violated in practice, noting that “apparent violations” of this condition are common, as the same microbe is found in multiple diseases. This amounts to an open concession that the criterion of specificity is routinely ignored, even as bacteriology continues to assert precise microbial causes for distinct disease entities:

Second, it must further be present in this disease and in no other, since otherwise it could not produce a special definite action. We often meet with apparent violations of this condition and find bacteria which we regard as specific, in the sense already explained, and whose occurrence is, nevertheless, not confined to one disease. Such exceptions are, however, explainable by the differences which various kinds of bacteria show according to the place of entrance, the organ they have attacked, the degree of susceptibility in the organism attacked, the degree of virulence which they possess, etc., etc. A careful consideration of all these different factors will suffice to guard against errors and false conclusions.

Rather than treating this as a serious challenge to the “theory,” however, Fraenkel resorts to special pleading. He excuses these contradictions by appealing to a list of flexible, unmeasurable variables: the site of “infection,” the host’s susceptibility, the microbe’s “virulence,” and so on. In doing so, he turns what should be a falsifiable criterion into an ever-adaptable explanation—one that protects the “theory” from scrutiny rather than exposing it to it.

The third postulate from Fraenkel is just as revealing—and problematic—as the previous two. It requires a strong, observable link between microbial presence and symptoms. At face value, this is a logical requirement: the microbe must be abundant and precisely located in a way that explains the symptoms. If the symptoms affect the lungs, the microbe should be in the lungs in sufficient quantities. If the symptoms are systemic, the distribution of the microbe should account for that. In other words, the physical presence of the microbe in the body must be causally linked to the observed pathology:

Third, a specific micro-organism must occur in such quantities and so distributed within the tissues that all the symptoms of the disease may be clearly attributable to it. On this point also the peculiar manner in which, under certain circumstances, the bacteria produce their effects demands careful attention. The answer to the question whether a particular bacterium fulfils these conditions or not is afforded by microscopic examination.

This is conducted according to ordinary well-known rules and requires no special explanation.”

But the problems begin immediately in how Fraenkel handles this crucial requirement. When describing the third condition—that a microbe must occur in sufficient quantity and distribution in tissue to explain all disease symptoms—he casually brushes it off by saying that this is “conducted according to ordinary well-known rules and requires no special explanation.”

This is a major red flag. While Fraenkel provides detailed descriptions elsewhere in the text for culturing bacteria, dissecting animals, and avoiding contamination, he completely sidesteps the deeper issue here: how do we logically and empirically determine that the microbe observed is actually producing the symptoms? There's no discussion of how tissue distribution is measured, how one distinguishes correlation from causation, or what threshold of microbial presence is deemed “sufficient” to explain disease.

In other words, he punts on what is arguably the most important and empirically demanding part of the theory. The vague reference to “microscopic examination” shifts the burden of proof away from demonstration and onto assumption. This rhetorical move—glossing over complexity with appeals to “ordinary rules”—is a textbook example of hand-waving. It substitutes confidence for clarity and sidesteps the very scrutiny that a valid scientific theory must withstand.

A final passage from Dr. Fraenkel reveals the fragile logic underpinning early claims of bacterial causation. He argued that if a bacterium consistently appears in all cases of a disease, occurs in large quantities, exhibits distinct characteristics, and is exclusive to that disease, then the probability that it causes the disease “approaches very near to certainty.” On the surface, this might sound persuasive—but it’s a textbook case of affirming the consequent, a well-known logical fallacy.

The structure of this reasoning goes as follows: If bacteria cause disease, then we should see them consistently present in the disease. We do see them present—therefore, they must be the cause. But this reverses the direction of valid inference. Just because the expected outcome of a hypothesis is observed does not prove the hypothesis is true. Many other explanations could lead to the same observation. In this case, bacteria might appear consistently because the diseased environment supports their growth, or because they are a secondary consequence, not a cause. The presence of bacteria in diseased tissue is merely a correlation—and drawing a causal conclusion from correlation without excluding other possibilities is precisely what makes the reasoning fallacious. Fraenkel’s argument does not demonstrate causation; it merely assumes it:

“If such a bacterium which (firstly) occurs in all cases of the disease in question and (secondly) occurs there in large quantities also presents marked peculiarities of growth or form, enabling us to distinguish it from other species and also to prove (thirdly) that this one definite species is found only and exclusively in connection with this one particular disease, we may fairly conclude that it stands in a particular intimate relation to this disease, and the probability of its being also the cause of this disease is so strong that it approaches very near to certainty.

Fraenkel himself acknowledges a critical weakness in the germ “theory” when he admitted that the only definitive evidence would be a successful transmission of the disease using a pure culture of the isolated microbe—something that would eliminate confounding variables potentially responsible for the illness. He even conceded that using material taken directly from a diseased organism is inconclusive because it may contain unknown substances that are actually responsible for causing the disease. Until a pure culture is shown to reproduce the disease, Fraenkel openly stated that it remains possible the bacteria are merely a consequence of the disease—or something that happens to appear alongside it—not its cause.

Despite these striking admissions, Fraenkel attempted to preserve the “theory” by asserting that such a “successful transmission” using a pure culture proves the specific character of a bacterium “indisputably.” In reality, it does no such thing. So-called “pure” cultures may still contain unrecognized contaminants, toxins, or culture-induced artifacts. And reproducing similar symptoms does not establish causation or specificity—it merely restates the conclusion as the proof:

The last link in the chain of evidence is of course supplied only by a successful transmission, before the overwhelming force of which all opposition must yield. Until that is obtained the objection is always possible that the bacteria may be a regular sequel or accompanying symptom of the disease, in consequence of the fact that certain morbid metamorphoses offer peculiar facilities for the development of certain bacteria. This view of the case has, it is true, an immense weight of probability against it, but it cannot be finally disproved without separating the bacteria from all their natural surroundings and experimenting with the pure culture, to find out whether the specific qualities attributed to them are still there or not.

Dr. Frankel conceded a major flaw in germ “theory’s” evidentiary foundation: when you take material directly from a sick organism and use it to “infect” another, you're introducing a mixture of unknown components. This means you cannot be sure that the disease is caused by the bacteria alone; it might be caused by something else in the mix—toxins, damaged tissue, host debris, etc. This admission undermines countless early (and even modern) experiments that rely on direct transfer from a diseased host without confirmed purification as “proof” of “infectious” causation. It should have placed the entire foundation of germ “theory” on more tentative ground.

Fraenkel then tried to save the argument by claiming that once a bacterium has been cultured and passed through multiple generations in the lab—isolated and grown over time—this concern disappears. He asserted that if disease symptoms are then reproduced using this supposedly “pure” culture, the causal link is “indisputably proved.”

But this leap is not logically valid. It is, in fact, a logical sleight of hand. A “pure” culture is only as pure as the assumptions and methods used to verify it. There could still be unseen contaminants, byproducts, or culture-induced changes that produce illness—especially when injected unnaturally into tissues or animals. Simply reproducing similar symptoms doesn’t prove that the same cause is at work, nor does it rule out alternative explanations:

As long as we continue to transmit virus obtained directly from a diseased organism, there is a possibility that other substances are inoculated along with the bacteria, and that these other substances contain the disease-causing matter. If, however, we take as our point of departure a culture which has been extended through several generations, the above objection collapses, and by the successful transmission—the reproduction of an affection like the original disease—the specific character of a given bacterium is indisputably proved.

Even more telling is Fraenkel’s fallback explanation for failed transmission attempts: he blamed it on host specificity—saying that certain microbes just won’t “infect” certain animals, and therefore failure to fulfill Koch’s Postulates in those cases isn’t a real failure. This amounts to immunizing the “theory” against falsification. No matter the outcome—success or failure—it’s always interpreted in favor of germ causation.

Unfortunately, we cannot yet fulfil this requirement in all cases. We have already often referred to the very different degrees of susceptibility possessed by the different species of animals as regards the attacks of the pathogenic micro-organisms, and when we reflect on the obstinate tenacity with which more highlyorganized parasites often attach themselves exclusively to one species of animal, which they never leave under any circumstances, we will no longer find it astonishing that the lower parasites cannot always be transmitted from one species of animal to another.

Rather than accepting failure to meet Koch's conditions as a refutation, Fraenkel continued to engage in special pleading—explaining away contradictions with unverifiable claims. The result is that the germ “theory,” as defended here, becomes effectively unfalsifiable. Any failure to meet its own criteria is met not with reconsideration, but with rationalization. This marks a shift away from scientific logic toward dogma—where the “theory” is preserved at all costs by propping it up not with rigorous logic but with rhetorical maneuvering, even at the expense of its own internal coherence.

Dr. Montague Leverson’s critique of Dr. Fraenkel’s version of Koch’s Postulates, while missing the context offered by a deeper look at his aforementioned statements, is still a pointed and layered dismantling of the logical framework underlying the germ “theory.” He exposed several core fallacies and assumptions that are relevant today—particularly begging the question, affirming the consequent, and the misuse of categorization (reification via nosology).

He began by scrutinizing the first postulate—the claim that the microbe must be present in all cases of a disease. Leverson argued that this is often accepted as true only because diseases are defined in such a way that they require the presence of the microbe by definition. If a case doesn’t show the expected germ, it may simply be reclassified or excluded, regardless of whether it shares all the clinical features of the disease. This creates a closed loop of reasoning: the disease is defined by the presence of the germ, and then the presence of the germ is cited as proof that it causes the disease. This is a textbook example of begging the question—a logical fallacy in which the conclusion is assumed in the premise. Rather than proving that the microbe causes the disease, the argument quietly presupposes it, thus avoiding the need for actual demonstration.

He further criticized the prevailing system of nosology—the classification of diseases—as being too detached from actual morbid processes. From his homeopathic perspective, he saw conventional disease labeling as an artificial structure that can obscure more than it reveals. This faulty classification, he argued, allows bacteriologists to manipulate categories in a way that appears to support their “theory” while actually avoiding falsification.

The first of these conditions constantly assumed present by the bacteriologists is true only by giving a name to a condition presenting certain symptoms, and excluding conditions which, though essentially alike, may present different symptoms; and even then the presence of such condition cannot be asserted in every instance of the finding of such micro-organism.

The error in this case arises chiefly through the use of a nosology by the old school which has little reference to the real morbid condition. The true homoeopath will readily appreciate this objection, but it will have little weight with persons habituated to the prevalent system of nosology, nor is it necessary for my present purpose to insist upon it.

Leverson then targeted the second and third postulates. The second, which requires that the microorganism not be found in any other disease, he said had never been satisfied for any so-called germ. The third, which claims the symptoms of the disease must be clearly attributable to the microorganism, assumes what it is meant to demonstrate. This again is classic begging the question. Leverson backed up his argument with the testimony of Professor Crocq, who reported that the cholera bacillus had been observed in cases of typhoid fever, simple stomach aches, and even in people who were completely healthy. While I was unable to locate the particular address by Professor Crocq that Dr. Leverson highlighted, Dr. Henry Raymond Rogers, M.D. made similar statements in June, 1895:

To the Editor:—Dr. Robert Koch has sought to explain the cause of certain diseases upon the hypothesis of the action of pathogenic germs, invisible to the human eye. Upon the microscopic examination of the stools of cholera cases, he found different forms and kinds of germs, and among these was one of comma-shape, which he fancied was the cause of this disease. Through the process of “culture,” and “experiment” upon the lower animals he asserts he has demonstrated that this germ is the actual cause of this disease. So confident was he that this newly discovered, comma-shaped object was the cause of cholera that for several years he continued to assert with the utmost assurance that the presence of these comma-shaped bacilli in the dejections of a person suspected of having this disease, constitutes positive evidence that the case is one of pure Asiatic cholera.

But this comma-shaped bacillus theory of cholera has proved a failure. These invisible comma-shaped germs are now found to be universal and harmless. They are found in the secretions of the mouth and throat of healthy persons, and in the common diarrheas of summer everywhere—they swarm in the intestines of the healthy and are observed in hardened fecal discharges as well. Dr. Koch to-day asserts that these bacilli are universally present. He even tells us that: “Water from whatever source frequently, not to say invariably, contains comma-shaped organisms.”

Drs. Pettenkofer of Munich and Emmerich of Berlin, physicians of high distinction and experts in this disease, drank each a cubic centimeter of “culture broth” which contained these bacilli, without experiencing a single symptom characteristic of cholera, although the draught in each instance was followed by liquid stools swarming with these germs.

Dr. Koch has kept au courant with the foregoing facts, as well as others quite as significant, and, had he accepted the evidences which thus year after year have been forced upon him, his pernicious cholera germ theory with its most disastrous consequences in misleading mankind would have been unknown to-day.

This observation directly contradicts the requirement that the germ be both specific to and necessary for the disease in question.

But the second of the above “conditions” has not been secured with regard to any of the so-called germs.

The same objection applies to the third condition, with the additional objection that it begs the whole question by assuming that symptoms may be “clearly attributed” to a specific micro-organism as a cause.

Neither the second nor third conditions has ever been attained, and from the nature of the case it seems impossible that either of them ever should be; nevertheless the bacteriologists, from Koch downwards, continually argue by assuming their existence in every case in which they have desired to set up bacterial peccancy; and yet Professor Crocq assures us that the supposed cholera bacillus is often found accompanying typhoid fever, a simple stomach ache, and even perfect health. (See his address before the Belgian Academy of Medicine, March 30th, 1895.)

Taken together, Leverson’s critique reveals that the germ “theory” of disease, as promoted by Koch and Fraenkel, is built on fragile logical foundations. Its proponents routinely assume the very points they need to prove, redefine diseases to suit their claims, and ignore or explain away contradictory evidence. Rather than offering a genuine scientific theory capable of withstanding scrutiny, Leverson showed that the germ “theory” relies on rhetorical maneuvering and selective interpretation of data.

Dr. Leverson next quoted Apollinaire Bouchadat, a supporter of vaccination, who nonetheless admitted before the French Academy that Pasteur’s claim—that every “contagious” disease is caused by a specific microbe—is “apparently true in some” but fails in many others, including some of the most well-known diseases like cholera, typhoid, smallpox, and yellow fever. Leverson emphasized that even within the scientific establishment, there was serious doubt and acknowledgment that the microbial hypothesis had not been validated across the board.

Leverson’s core critique, though, is logical. Even if all three of Fraenkel's limited version of Koch’s rules were fulfilled—and he and others have already shown they are not—Leverson insisted that they would still be insufficient to establish microbial causation. Why? Because there is a categorical difference between finding microbes in diseased tissue and injecting them into an organism to see what happens. The former is observational; the latter is interventionist. These are entirely different conditions, and equating them—as germ theorists routinely do—is a logical fallacy. Leverson point is that a controlled inoculation experiment through injection introduces new variables and does not replicate the natural development of disease.

This issue—the fallacy of believing that disease induced by injecting foreign biological material is equivalent to proving natural “infection” and “contagion”—was sharply exposed by Professor Henry Formad in his 1884 paper The Bacillus Tuberculosis and the Etiology of Tuberculosis-Is Consumption Contagious?. By compiling numerous cases in which researchers induced tuberculosis-like disease using substances other than the tuberculosis bacillus, Formad demonstrated that artificially producing illness through injection does not logically support the claim that the same disease arises through natural exposure. His point was that the ability to provoke symptoms via unnatural routes—especially with varied, non-specific materials—undermines the inference that a specific germ causes the disease in nature. It exposes the fallacy of equating experimental induction with natural etiology.

The following observers all refer to many or few experiments of their own, in which tuberculosis resulted from the inoculation with either innocuous substances or with specific matters other than tuberculous:

Lebert, Atlgem. Med. Central Zeitung; 1866.

Lebert and Wyss, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. xl, 1867.

Empis, Report of the Paris Internat. Med Congress, 1867.

Bunion Sanderson, British Med. Journal, 1868.

Wilson Fox, British Med. Journal, 1868.

Langhans, Habilitationschrift, Marburg, 1867.

Clark, The Medical Tithes, 1867.

Waldenburg, Die Tuberculose, etc., Berlin, 1869.

Papillon, Nicol, and Leveran, Gaz. des Hop., 1871.

Bernhardt, Deutsch. Arch. f. Klin. Med., 1869.

Gerlach, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. li , 1870.

Foulis, Glasgow Med. Journal, 1875.

Perls, Allgemeine Pathologie, 1877.

Grohe, Berliner Klin. Wochenschr, No. I, 1870.

Cohnheim and Fränkel, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. xlv, 1869.

Knauff, 4îte Versamml. Deutsch. Naturforscher, Frankfort.

Ins. Arch f. Experim. Pathologie, vol v, 1876.

Wolff, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. Ixvii, 1867.

Ruppert, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. lxxii, 1878.

Schottelius, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. lxxiii, 1878 ; ibid., xci, 1883.

Virchow, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. lxxxii, 1880.

Strieker, Vorlesungen über Exp. Pathologie, Wien., 1879.

Martin, Med. Centralblatt, 1880, No. 42.

Wood and Formad, National Board of Health Bulletin, Supplement No. 7, 1880.

Robinson, Philadelphia Med. Times, 1881.

Weichselbaum, Med. Centralblatt, No. 19, 1882, and Med. Jahrbücher, 1883.

Balough, Wiener Mcdiz. Blatter, No. 49, 1882.

Wargunin, Allg. Med. Centralblatt, April 8, 1882

Hansell Arch. f. Ophthalmologie, vol. xxv.

This mistaken inference assumes that outcomes from unnatural, invasive methods validate hypotheses about how disease develops in real-world conditions—an error in reasoning that conflates correlation with causation and violates the principle of equivalence between experimental and natural contexts.

Similarly, Dr. Edward Charles Spitzka, a respected neurologist of the late 19th century, demonstrated in his paper How Can We Prevent False Hydrophobia? that symptoms of rabies—or “hydrophobia”—could be artificially produced in dogs by introducing virtually any foreign substances into the brain. Using Pasteur’s own trepanning technique, Spitzka injected soft soap, calf’s marrow, calf’s kidney, and even the spinal cord of a man said to have died of rabies. In every case, the dogs developed behaviors resembling madness, including “epileptic delirium.” Dr. Spitzka concluded that the “method of demonstrating rabies by direct inoculation of the brain is fallacious” and that rabies diagnoses were being obtained through “misleading methods.”

Dr. Leverson further exposed another foundational flaw: the so-called “pure cultures” used in inoculation experiments are not actually pure in any scientifically meaningful sense. These preparations are intermingled with toxins, metabolic byproducts, cellular debris, and residues from the culture medium itself. As a result, even if disease appears after inoculation, one cannot logically attribute causation to the germ alone—because the experimental setup introduces multiple potential variables simultaneously. There is no way to rule out whether the illness was triggered by the presumed “pathogen,” the toxins, or some other confounding element in the mixture.

This violates a core principle of the scientific method: the necessity of a valid independent variable. In order for an experiment to be scientifically legitimate, the independent variable—the presumed cause—must be clearly isolated and controlled, such that no other factors could plausibly account for the observed outcome. If multiple possible causes are introduced together, and an effect is observed, it becomes impossible to know which factor (if any) was responsible. Leverson recognized this logical failure and thus argued for an additional requirement to be added to Koch’s Postulates as outlined by Fraenkel: not only must the germ be present in disease, but all other sufficient causes must be excluded. Without this, causation cannot be established. Instead, what is claimed as “proof” is nothing more than a correlation polluted by experimental noise.

Mr. Bouchadat, an advocate of vaccination, stated before the French Academy: “The system of Pasteur, that every contagious and virulent disease has for its cause a microbe, a pre-existent specific germ floating in the atmosphere or deposited on the earth, apparently true in some, fails in many well defined cases.” He then specified hydrophobia, syphilis, typhus, cholera, small-pox, typhoid, yellow fever, and the plague, of which the supposed microbe has been disproved!

But even if all the conditions prescribed by Koch’s three rules were complied with, they would be insufficient, logically, to establish the conclusion drawn from their supposed presence. It must be remembered that the inoculation of so-called germs into a human or other living body is an entirely different process from that which occurred when they have been found in a condition of disease. The conditions are so entirely different that one is at a loss to account for their confusion. But, further, even the inoculation is defective. These supposed germs being cultivated in certain media, are so inseparably intermixed with their respective cultures and the poisons produced therein, that it is impossible to determine whether the so-called germs or their accompaniments produce the diseased conditions that follow the inoculation. Koch, Pasteur, Fraenkel, DeBary, Pruden, and their numerous disciples must add another rule to the “three fixed and definite rules laid down with exactness and precision by Koch” before any, even a mere tyro, in logical reasoning can accept their conclusions. Not only must “the germ in question be proved present in all cases of the disease in question,” according to the second of the Kochean rules, but all other sufficient causative matters and conditions must be absent.

This no manipulation has been able to effect, and all that bacteriology has really shown is that certain so-called germs do often accompany certain diseases, but whether as cause or effect remains at present unknown, with a great preponderant probability in favor of the latter, while as Professor Crocq has shown they are often present in the organism without any disease.*

In the footnotes, Dr. Leverson mentioned that he had recently come across a work by Dr. H. Boucher titled Origines Epidemiques, which he felt completely overthrew the germ “theory” of disease:

*In Origines Epidemiques, a work I have only just come across, (Nancy A. Nicolle, publisher, 1896,) Dr. H. Boucher, of Saint Servain, France, completely overthrows the “germ theory.” He shows that the so called germs are almost always, when present, the products, not the causes of disease, and that organic fermentation together with climatic conditions, acting on susceptible cases are the true causes of disease.—M. R. L.

While I’m unable to provide a full translation of the book—it spans 237 pages and is written in French—I want to offer a short summary of some key points from the introduction.

Dr. Boucher opened by observing how his earlier pamphlet—critical of germ “theory”—was poorly received by the scientific establishment, which he refers to as “the powerful.” This, he said, was entirely to be expected, since his arguments exposed the “gigantic errors” upon which their prestige and professional identity rested. No substantive refutation was offered—only deflection and ad hominem dismissal. Critics either claimed his timing was “inopportune,” admitted they couldn’t afford to challenge the very microbe that sustained their careers, or misrepresented his views entirely.

Boucher sharply criticized bacteriology as a dogmatic belief system rather than a genuine science. He described it as “a religion more than science,” complete with “pontiffs,” “sacred rites,” and an unquestioned “cult” around microbes. He noted how critics of bacteriology were often dismissed without engagement, writing:

“Living on this same microbe which kills mere mortals, they could not bear that anyone dared to touch it.”

He also mocked the irrationality of one critic who accused him of, like some ancients, “believing that theories must precede facts.” To this, Boucher replied with biting sarcasm:

“I don't really see how a modest human being... could construct a theory on facts that he doesn't know and can't know, since they haven't yet occurred.”

When accused of relying on mere hypotheses, Boucher turned the charge back on the bacteriologists:

“The science [they] propagate rests from start to finish on this method of demonstration.”

He went on to list the many layered assumptions required to preserve germ “theory”—from the hypothesis of microbial self-harmfulness, to “contagion,” to “latent microbism,” adding:

“I would never finish if I wanted to talk about the hypotheses of toxic secretion of the bacillus, the loss and resumption of virulence, etc.”

In contrast, Boucher offered a unified view:

“A single principle coexisting in a latent state in all beings... elaborated by the organism subjected to certain influences.”

He saw bacteriology’s decline as inevitable:

“We see that bacteriology has left the summits... it is beginning to roll down the slope.”

“The voice of truth could be stifled for a while... but the idea sown would not germinate less.”

Judging from the introduction, Dr. Boucher's book offers a humorous and scathing takedown of the germ “theory.” It’s likely a work worth coming back to for a more detailed examination in the future.

Returning to Dr. Leverson, he continued his critique by targeting the claims of staphylococcus and streptococcus as causative agents of suppuration. He pointed out a significant contradiction in Fraenkel’s work, where Fraenkel asserted that staphylococcus is the cause of pus formation through “successful transmissions,” yet earlier in the same text admitted that certain chemical substances, like nitrate of silver and turpentine, can independently produce acute suppuration. This inconsistency undermines the idea that bacteria are the necessary cause of pus formation, suggesting that inflammation can occur due to non-biological factors.

Leverson also questioned why these bacteria, supposedly ubiquitous in the environment, only cause illness sporadically. If they are always present in the air, what determines whether they cause suppuration in some individuals and not others? This highlights a failure in the bacteriological explanation, as it cannot account for the variability of disease outcomes.

Dr. Leverson raised the issue of why some individuals develop boils or carbuncles while others do not, even when the same bacteria are present. He challenged bacteriology’s inability to explain these differences and pointed out that no bacteriologist had yet addressed why certain bacteria appear with conditions like carbuncles or anthrax while others do not. Leverson also introduced doubts about the very nature of bacteria, citing researchers who question whether these germs are truly living organisms capable of reproduction, thus challenging a core tenet of germ “theory.”

Critiquing the methodology of inoculation experiments, Leverson argued that because the bacteria are always mixed with other substances—unknown in both quality and quantity—no valid conclusions can be drawn about their causal role in disease. His overall argument is that the germ “theory,” while widely accepted, remains filled with contradictions, unanswered questions, and methodological flaws, leaving its foundational claims unsupported and speculative.

An example almost daily presented to the practicing physician ought to guard him against coming to any conclusion in favor of the bacterial origin of disease.

One or other form of the staphylococcus or streptococcus has always been found in pus; so much so, that Fraenkel has been led to assert, “The fact that the staphylococcus is not a regular and harmless concomitant of purulent inflammatory processes, but their cause, has been demonstrated (?) by successful transmissions.” (Fraenkel’s Bacteriology, by Lindsley, p. 323.) Yet two pages earlier (p. 321) he stated: “The investigations of Scheurlen, Steinhaus, Kaufman, and especially Gravity and De Bary, leave us no longer in doubt as to the fact that many germ-free chemical substances (such as Nitrate of Silver, Oil of Turpentine, Liquor Ammonia, Caustici, Digitaline, Cadaverine, etc.) can produce an acute suppuration in the subcutaneous tissue.”

Now in the very common occurrence of sporadic cases of boils and carbuncles, without any other apparent diseased condition, if these germs are the cause thereof, how did they get into the body to produce suppuration? If, as alleged by some, they are always present in the air, what determines them to cause suppuration once in a while, in this or that individual, while at other times he feels no ill effects? This reasoning is specially forcible with regard to the deeply seated carbuncle; and why the staphylococcus should cause a boil today, or in one person, and a carbuncle at another time or in different persons, or why sometimes anthrax should be present with carbuncle and only the staphylococcus or streptococcus at other times, are questions which no bacteriologist has attempted to answer; and until full answers are given to these questions, the theories of Koch, Pasteur, and their followers remain the barest assumptions.

Nor should it be forgotten that with regard to many of the so-called germs, evidence is lacking to prove that they possess life or are capable of reproduction, either by sporulation or segmentation.

M. Chavée Leroy, of Claremont (France), and Dr. Ed. Fournié, the learned editor of the Revue Medicale of Paris, have raised grave doubts upon these questions.

As occurring in fact then in inoculations the so-called germs are intermixed inseparably with other things unknown both as to quality and quantity and, so intermixed, are injected by, or inoculated into living beings.

Dr. Leverson delivered a sharp critique of the logical structure underlying bacteriology by reducing its reasoning to a simple syllogism. He showed that the germ theorists’ argument follows this form: certain germs, under certain conditions, are associated with specific diseases (“some A’s are B’s”); those diseases are observed under both these and other unknown conditions (“some B’s are C’s”); and from this, bacteriologists conclude that all such diseases are caused by the germs (“all C’s are A’s”). Leverson pointed out that this leap in logic is entirely unwarranted—the conclusion does not follow from the premises. It's a textbook example of invalid reasoning, conflating correlation with causation and generalizing from partial evidence.

To underscore the absurdity of this reasoning, he sarcastically suggested that perhaps medical students should be required to pass an exam in logic before graduating or even entering medical school: “In view of such logic would it not be in order to require candidates for the degree of doctor of medicine to pass a satisfactory examination in the art of reasoning...?” With this critique, Leverson reframed the debate as one not merely about scientific evidence, but about reasoning itself—arguing that germ “theory” fails even the most basic test of logical coherence.

Let us now reduce the theory of the bacteriologists, as by them applied in practice to the form of a syllogism, and by so doing the real logical basis of that theory will be more readily perceived.

Certain germs under certain conditions (i. e., such as just mentioned) produce certain diseases;

Or, some A’s are B’s.Such diseases occur under these conditions, and under other (unknown) conditions;

Or, some B’s are C’s.Therefore, all such diseases are caused by the germs, or all C’s are A’s!

In view of such logic would it not be in order to require candidates for the degree of doctor of medicine to pass a satisfactory examination in the art of reasoning as a condition of graduation, if not even of entering a medical college? At least,—that is—if any examination is to be insisted on as preliminary to the practice of the art of healing.

Dr. Leverson employed biting satire in his anecdote about an old Irish doctor who, after a lifetime of embracing every emerging medical theory, is finally confronted with the germ “theory” but finds it difficult to accept. One day, upon encountering the foul smell of a decomposing donkey, he investigates and discovers it teeming with maggots. Suddenly, the germ theory “becomes clear to him as a revelation,” and he exclaims, “tis the maggots kilt him sure!”

Leverson used this story to lampoon the flawed reasoning at the heart of germ “theory”—mistaking the presence of microbes for proof of causation. Just as maggots appear after death and do not cause it, he suggests that bacteria often arise as a result of disease, not its source. This plays on the classic logical fallacy known as post hoc ergo propter hoc—Latin for “after this, therefore because of this.” The fallacy assumes that just because one event follows another, the first must have caused the second.

In this case, the error lies in observing bacteria in diseased tissue and concluding that they must be the cause, simply because they are present after the onset of illness. But presence alone—especially after the fact—does not prove causation. Just as maggots are not what killed the donkey, but arrive as a natural result of its decomposition, microbes may appear as a consequence of the body’s breakdown or imbalance, not as its instigators. The final jab—“History is silent as to the Medical College from which our hero graduated!”—underscores the absurdity of drawing such conclusions and mocked the intellectual rigor of those who do. Through humor, Leverson highlighted this basic but critical fallacy and questioned the scientific validity of attributing disease to microbes based solely on temporal association.

A story goes, that an old Irish doctor who had diligently studied all the chemisal, physiological, and biological medical theories of his day, accepting with ardor every new theory as it arose, had all his convictions disturbed by the rise of the germ theory, which he was unable quite to accept. Walking one day on the road to Limerick, his Olfactory organs were assailed by the odoriferous emanations which, with a revival of his youthful love of investigation, he soon traced to the decomposing carcass of an ass. Following up the bent given to his mind in youth, he at once resolved on pursuing a closer investigation, and he soon discovered that the cadaver teemed with maggots. At once his mind was illuminated,his past doubts were swept away, the germ theory in all its beauty became clear to him as a revelation! “Poor baste,” said he, compassionately, “sure ’tis aisy to see what ailed him; ’tis the maggots kilt him sure!”

History is silent as to the Medical College from which our hero graduated!

Dr. Leverson closed his paper with a powerful synthesis of his philosophical, physiological, and logical objections to germ “theory”—anchoring his argument not only in scientific skepticism, but in a holistic view of human health. He emphasized that disease should be understood as a consequence of systemic imbalance, not the arbitrary invasion of microbes. The human body, he argued, requires proper air, water, food, exercise, and rest. When these are absent, deficient, or excessive, the body weakens, becomes toxic, and then manifests illness. What the microscopist wrongly attributes to germs, Leverson saw as internal dysfunction caused by environmental, lifestyle, and constitutional factors.

He critiqued the modern tendency to reify disease with specific names—as if they are distinct, external entities—and praised Samuel Hahnemann—considered the founder of homeopathy—for exposing this fallacy. In the Organan of Medicine, Hahnemann criticized the medical practice of assigning fixed names to diseases as if they represent uniform, unchanging conditions. He argued that such labels often group together very different illnesses based on superficial similarities, which leads to inappropriate, one-size-fits-all treatments. Instead, he emphasized that true healing requires individualized assessment based on the totality of each patient’s symptoms—not on a misleading disease name.

“How can the bestowal of such a name justify an identical medical treatment? And if the treatment is not always to be the same, why make use of an identical name which postulates an identity of treatment?”

“From all this it is clear that these useless and misused names of diseases ought to have no influence on the practice of the true physician, who knows that he has to judge of and to cure diseases, not according to the similarity of the name of a single one of their symptoms, but according to the totality of the signs of the individual state of each particular patient, whose affection it is his duty carefully to investigate, but never to give a hypothetical guess at it.”

Two other relevant quotes from Hahnemann further support Dr. Leverson’s position by underscoring his rejection of simplistic disease labels and emphasizing a holistic, individualized approach to health:

“While inquiring into the state of chronic diseases the particular circumstances of the patient with regard to his ordinary occupation, his usual mode of living and diet, his domestic situation and so forth, must be well considered and scrutinized to ascertain what there is in them that may tend to produce or to maintain disease in order that by their removal the recovery may be promoted.”

“The first duty of the homoeopathic physician who appreciates the dignity of his character and the value of human life is, to inquire into the whole condition of the patient, the cause of the disease as far as the patient remembers it, his mode of life, the nature of his mind, the tone and character of his sentiments, his physical constitution and especially the symptoms of the disease. This inquiry is made according to the rules laid down in the Organon. This being done, the physician then tries to discover the true homoeopathic remedy. He may avail himself of the existing repertories with a view of becoming approximately acquainted with the true remedy. But, inasmuch as these repertories only contain general indications, it is necessary that the remedies which the physician finds indicated in those works should be afterwards studied out in the materia mediea. A physician who is not willing to take this trouble, but who contents himself with the general indications furnished by the repertories and who, by means of these general indications, dispatches one patient after the other, deserves not the name of a true homoeopathist.”

In a particularly striking example supporting this view, Leverson reframed smallpox not as a deadly threat to be eradicated by vaccines, but as a “safety valve” for the body—a natural method of expelling accumulated toxins when primary organs of excretion fail. Citing Thomas Sydenham, he noted that years of high smallpox incidence often correlate with lower overall mortality, challenging the assumption that the disease is inherently destructive. This view echoes traditional naturopathic and homeopathic philosophies, where symptoms are seen as the body's intelligent attempts to heal.

While I could not locate the exact passage Leverson referenced, Sydenham did express a similar view in a letter dated April 22, 1688. In it, he described smallpox—though widely feared—as one of the mildest and safest diseases when left untreated. He condemned the role of physicians and nurses in worsening outcomes, arguing that misguided interventions based on faulty concepts like “malignancy” often caused more harm than the disease itself. In Sydenham’s view, it might have been better if medicine had never interfered at all:

It is a disease, wherein, as I have been more exercised this year than ever I thought I could have been, so I have discovered more of its days than ever I thought I should have done. It would be too large for a letter, to give you an account of its history; only in general I find no variolis, but do regret greatly, that I did not say, that, considering the practices that obtain, both amongst learned and ignorant physicians, it had been happy for mankind, that either the art of physic had never been exercised, or the notion of malignity never stumbled upon. As it is palpable to all the world, how fatal that disease proves to many of all ages, so it is most clear to me, from all the observations that I can possibly make, that if no mischief be done, either by physician or nurse, it is the most slight and safe of all other diseases.

Dr. Leverson asserted that true disease prevention lies not in vaccines or microbe-hunting, but in health itself: “the only true prophylactic against any and all disease is health.” It is the removal of the causes of weakened vitality—poor nutrition, dirty water, polluted air, inadequate rest—that safeguards wellness, not pharmaceutical interventions.